Полная версия

Полная версияПолная версия:

Life of Napoleon Bonaparte. Volume IV

Thus did a Prussian general first set the example of deserting the cause in which he served so unwillingly – an example which soon spread fast and far. It was a choice of difficulties on D'Yorck's side, for his zeal as a patriot was in some degree placed in opposition to the usual ideas of soldierly honour. But he had not left Macdonald till the Maréchal's safety, and that of the remainder of his army, was in some measure provided for. He was out of the Russian territory, and free, or nearly so, from Russian pursuit. D'Yorck had become neutral, but not the enemy or his late commander.

Here the question arises, how long were the Prussians to be held bound to sacrifice their blood for the foreigners, by whom they had been conquered, pillaged, and oppressed; and to what extent were they bound to endure adversity for those who had uniformly trampled on them during their prosperity? One thing, we believe, we may affirm with certainty, namely, that D'Yorck acted entirely on his own responsibility, and without any encouragement, direct or indirect, from his sovereign. Nay, there is room to suppose, that though the armistice of Taurogen was afterwards declared good service by the King of Prussia, yet D'Yorck was not entirely forgiven by his prince for having entered into it. It was one of the numerous cases, in which a subject's departing from the letter of the sovereign's command, although for that sovereign's more effectual service, is still a line of conduct less grateful than implicit obedience. Upon receiving the news, Frederick disavowed the conduct of his general, and appointed Massenbach and him to be sent to Berlin for trial. But the officers retained their authority, for the Prussian army and people considered their sovereign as acting under the restraint of the French troops under Augereau, who then occupied his capital.

Macdonald, with the remains of his army, reduced to about 9000 men, accomplished his retreat to Königsberg after a sharp skirmish.

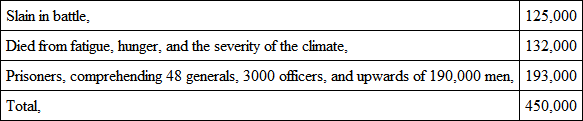

CLOSE OF THE RUSSIAN EXPEDITIONAnd thus ended the memorable Russian expedition, the first of Napoleon's undertakings in which he was utterly defeated, and of which we scarce know whether most to wonder at the daring audacity of the attempt, or the terrific catastrophe. The loss of the grand army was total, and the results are probably correctly stated by Boutourlin as follows: —

The relics of the troops which escaped from that overwhelming disaster, independent of the two auxiliary armies of Austrians and Prussians, who were never much engaged in its terrors, might be about 40,000 men, of whom scarcely 10,000 were Frenchmen.234 The Russians, notwithstanding the care that was taken to destroy these trophies, took seventy-five eagles, colours, or standards, and upwards of 900 pieces of cannon.

Thus had the greatest military captain of the age, at the head of an innumerable array, rushed upon his gigantic adversary, defeated his army, and destroyed, or been the cause of the destruction of his capital, only to place himself in a situation where the ruin of nearly the whole of his own force, without even the intervention of a general action, became the indispensable price of his safe return.

CAUSES OF THE CATASTROPHEThe causes of this total and calamitous failure lay in miscalculations, both moral and physical, which were involved in the first concoction of the enterprise, and began to operate from its very commencement. We are aware that this is, with the idolaters of Napoleon, an unpalatable view of the case. They believe, according to the doctrine which he himself promulgated, that he could be conquered by the elements alone. This was what he averred in the twenty-ninth bulletin. Till the 6th November he stated that he had been uniformly successful. The snow then fell, and in six days destroyed the character of the army, depressed their courage, elated that of the "despicable" Cossacks, deprived the French of artillery, baggage, and cavalry, and reduced them, with little aid from the Russians, to the melancholy state in which they returned to Poland. This opinion Napoleon wished to perpetuate in a medal, on which the retreat from Moscow is represented by the figure of Eolus blowing upon the soldiers, who are shown shrinking from the storm, or falling under it. The same statement he always supported; and it is one of those tenets which his extravagant admirers are least willing to relinquish.

Three questions, however, remain to be examined ere we can subscribe to this doctrine. – I. Does the mere fall of snow, nay, a march through a country covered with it, necessarily, and of itself, infer the extent of misfortune here attributed to its agency? – II. Was not the possibility of such a storm a contingency which ought in reason to have entered into Napoleon's calculations? – III. Was it the mere severity of the snow-storm, dreadful as it was, which occasioned the destruction of Buonaparte's army; or, did not the effects of climate rather come in to aid various causes of ruin, which were inherent in this extravagant expedition from the very beginning, and were operating actively, when the weather merely came to their assistance?

On the first question it is needless to say much. A snow, accompanied with hard frost, is not necessarily destructive to a retreating army. The weaker individuals must perish, but, to the army, it affords, if they are provided for the season, better opportunities of moving than rainy and open weather. In the snow, hard frozen upon the surface, as it is in Russia and Canada, the whole face of the country becomes a road; and an army, lightly equipped, and having sledges instead of wains, may move in as many parallel columns as they will, instead of being confined, as in moist weather, to one high-road, along which the divisions must follow each other in succession. Such an extension of the front, by multiplying the number of marching columns, must be particularly convenient to an army which, like that of Napoleon, is obliged to maintain itself as much as possible at the expense of the country. Where there are only prolonged columns, following each other over the same roads, the marauders from the first body must exhaust the country on each side; so that the corps which follow must send their purveyors beyond the ground which has been already pillaged, until at length the distance becomes so great, that the rearward must satisfy themselves with gleaning after the wasteful harvest of those who have preceded them. Supposing six, eight, or ten columns marching in parallel lines upon the same front, and leaving an interval betwixt each, they will cover six, eight, or ten times the breadth of country, and of course supply themselves more plentifully, as well as much more easily. Such columns, keeping a parallel front, can, if attacked, receive reciprocal aid by lateral movements more easily than when assistance must be sent from the van to the rear of one long moving line; and the march being lateral on such occasions, does not infer the loss of time, and other inconveniences inferred by a counter-march from the front to support the rear. Lastly, the frost often renders bridges unnecessary, fills ravines, and makes morasses passable; thus compensating, in some degree, to a marching army, for the rigorous temperature to which it subjects them.

But, 2dly, It may be asked, if frost and snow are so irresistible and destructive in Russia, as to infer the destruction of whole armies, why did not these casualties enter into the calculations of so great a general entering on such an immense undertaking? Does it never snow in Russia, or is frost a rare phenomenon there in the month of November? It is said that the cold weather began earlier than usual. This, we are assured, was not the case; but, at any rate, it was most unwise to suffer the safety of an army, and an army of such numbers and importance, to depend on the mere chance of a frost setting in a few days sooner or later.235

The fact is, that Napoleon, whose judgment was seldom misled save by the ardour of his wishes, had foreseen, in October, the coming of the frost, as he had been aware, in July, of the necessity of collecting sufficient supplies of food for his army, yet without making adequate provision against what he knew was to happen, in either case. In the 22d bulletin, it is intimated, that the Moskwa, and other rivers of Russia, might be expected to be frozen over about the middle of November, which ought to have prepared the Emperor for the snow and frost commencing five or six days sooner; which actually took place. In the 26th bulletin, the necessity of winter-quarters is admitted, and the Emperor is represented as looking luxuriously around him, to consider whether he should choose them in the south of Russia, or in the friendly country of Poland. The weather is then stated to be fine, "but on the first days of November cold was to be expected. Winter-quarters, therefore, must be thought upon; the cavalry, above all, stand in need of them."

It is impossible that he, under whose eye, or by whose hand, these bulletins were drawn up, could have been surprised by the arrival of snow on the 6th November. It was a probability foreseen, though left unprovided for.

Even the most ordinary precaution, that of rough-shoeing the horses of the cavalry and the draught-horses, was totally neglected; for the bulletins complain of the shoes being smooth. This is saying, in other words, that the animals had not been new-shod at all; for French horses may be termed always rough-shod, until the shoes are grown old and worn smooth through use. If, therefore, frost and snow be so very dangerous to armies, Napoleon wilfully braved their rigour, and by his want of due preparations, brought upon himself the very disaster of which he complained so heavily.

Thirdly, Though unquestionably the severity of the frost did greatly increase the distress and loss of an army suffering under famine, nakedness, and privations of every kind, yet it was neither the first, nor, in any respect, the principal, cause of their disasters. The reader must keep in remembrance the march through Lithuania, in which, without a blow struck, Napoleon lost 10,000 horses at once, and nearly 100,000 men, when passing through a country which was friendly. Did this loss, which happened in June and July, arise from the premature snow, as it has been called, of the 6th of November? No, surely. It arose from what the bulletin itself describes as "the uncertainty, the distresses, the marches and counter-marches of the troops, their fatigues and sufferances;" to the system, in short, of forced marches, by which, after all, Napoleon was unable to gain any actual advance. This cost him one-fourth, or nearly so, of his army, before a blow was struck. If we suppose that he left on both his flanks, and in his rear, a force of 100,000 men, under Macdonald, Schwartzenberg, Oudinot, and others, he commenced the actual invasion of Russia Proper with 200,000 soldiers. A moiety of this large force perished before he reached Moscow, which he entered at the head of less than 100,000 men. The ranks had been thinned by fatigue, and the fields of battle and hospitals must answer for the remainder. Finally, Napoleon left Moscow on the 19th October, as a place where he could not remain, and yet from which he saw no safe mode of exit. He was then at the head of about 120,000 men; so much was his army recruited by convalescents, the collection of stragglers, and some reserves which had been brought up. He fought the unavailing though most honourably sustained battle of Malo-Yarowslavetz; failed in forcing his way to Kalouga and Toula; and, like a stag at bay, was forced back on the wasted and broken-up road to Smolensk by Borodino. On this road was fought the battle of Wiazma, in which the French loss was very considerable; and his columns were harassed by the Cossacks at every point of their march, and many thousands of prisoners were taken. Two battles so severely fought, besides the defeat of Murat and constant skirmishes, cost the French, in killed and wounded, (and every wounded man was lost to Napoleon,) not less than 25,000 men; and so far had the French army been diminished.

This brought him to the 6th November, until which day not a flake had fallen of that snow to which all his disasters are attributed, but which in fact did not commence until he had in a great measure experienced them. By this time also, his wings and reserves had undergone severe fighting and great loss, without any favourable results. Thus, wellnigh three-fourths of his original army were destroyed, and the remnant reduced to a most melancholy and disorderly condition, before commencement of the storm to which he found it afterwards convenient to impute his calamities. It is scarcely necessary to notice, that when the snow did begin to fall, it found Napoleon not a victor, but a fugitive, quitting ground before his antagonists, and indebted for his safety, not to the timidity of the Russians, but to the over-caution of their general. The Cossacks, long before the snow-tempest commenced, were muttering against Koutousoff for letting these skeletons, as they called the French army, walk back into a bloodless grave.

When the severe frost came, it aggravated greatly the misery, and increased the loss, of the French army. But Winter was only the ally of the Russians; not, as has been contended, their sole protectress. She rendered the retreat of the grand army more calamitous, but it had already been an indispensable measure; and was in the act of being executed at the lance-point of the Cossacks, before the storms of the north contributed to overwhelm the invaders.

What, then, occasioned this most calamitous catastrophe? We venture to reply, that a moral error, or rather a crime, converted Napoleon's wisdom into folly; and that he was misled, by the injustice of his views, into the great political, nay, military errors, which he acted upon in his attempt to realize them.236

We are aware there are many who think that the justice of a quarrel is of little moment, providing the aggressor has strength and courage to make good what his adversary murmurs against as wrong. With such reasoners, the race is uniformly to the swift, and the battle to the strong; and they reply to others with the profane jest of the King of Prussia, that the Deity always espouses the cause of the most powerful. But the maxim is as false as it is impious. Without expecting miracles in this later age, we know that the world is subjected to moral as well as physical laws, and that the breach of the former frequently carries even a temporal punishment along with it. Let us try by this test the conduct of Napoleon in the Russian war.

The causes assigned for his breach with Russia, unjust in their essence, had been put upon a plan of settlement; yet his armies continued to bear down upon the frontiers of the Russian Empire; so that to have given up the questions in dispute, with the French bayonets at his breast, would have been on the part of Alexander a surrender of the national independence. The demands of Napoleon, unjust in themselves, and attempted to be enforced by means of intimidation, it was impossible for a proud people, and a high-spirited prince, to comply with. Thus the first act of Buonaparte went to excite a national feeling, from the banks of the Boristhenes to the wall of China, and to unite against him the wild and uncivilized inhabitants of an extended empire, possessed by a love to their religion, their government, and their country, and having a character of stern devotion, which he was incapable of estimating. It was a remarkable characteristic of Napoleon, that when he had once fixed his opinion, he saw every thing as he wished to see it, and was apt to dispute even realities, if they did not coincide with his preconceived ideas. He had persuaded himself, that to beat an army and subdue a capital, was, with the influence of his personal ascendency, all that was necessary to obtain a triumphant peace. He had especially a confidence in his own command over the minds of such as he had been personally intimate with. Alexander's disposition, he believed, was perfectly known to him; and he entertained no doubt, that by beating his army, and taking his capital, he should resume the influence which he had once held over the Russian Emperor, by granting him a peace upon moderate terms, and in which the acknowledgment of the victor's superiority would have been the chief advantage stipulated. For this he hurried on by forced marches, losing so many thousands of men and horses in Lithuania, which an attention to ordinary rules would have saved from destruction. For this, when his own prudence, and that of his council, joined in recommending a halt at Witepsk or at Smolensk, he hurried forward to the fight, and to the capture of the metropolis, which he had flattered himself was to be the signal of peace. His wishes were apparently granted. Borodino, the bloodiest battle of our battling age, was gained – Moscow was taken – but he had totally failed to calculate the effect of these events upon the Russians and their emperor. When he expected their submission, and a ransom for their capital, the city was consumed in his presence; yet even the desertion and destruction of Moscow could not tear the veil from his eyes, or persuade him that the people and their prince would prefer death to disgrace. It was his reluctance to relinquish the visionary hopes which egotism still induced him to nourish, that prevented his quitting Moscow a month earlier than he did. He had no expectation that the mild climate of Fontainbleau would continue to gild the ruins of Moscow till the arrival of December; but he could not forego the flattering belief, that a letter and proposal of pacification must at last fulfil the anticipations which he so ardently entertained. It was only the attack upon Murat that finally dispelled this hope.

Thus a hallucination, for such it may be termed, led this great soldier into a train of conduct, which, as a military critic, he would have been the first to condemn, and which was the natural consequence of his deep moral error. He was hurried by this self-opinion, this ill-founded trust in the predominance of his own personal influence, into a gross neglect of the usual and prescribed rules of war. He put in motion an immense army, too vast in numbers to be supported either by the supplies of the country through which they marched, or by the provisions they could transport along with them. And when, plunging into Russia, he defeated her armies and took her metropolis, he neglected to calculate his line of advance on such an extent of base, as should enable him to consolidate his conquests, and turn to real advantage the victories which he attained. His army was but precariously connected with Lithuania when he was at Moscow, and all communication was soon afterwards entirely destroyed. Thus, one unjust purpose, strongly and passionately entertained, marred the councils of the wise, and rendered vain the exertions of the brave. We may read the moral in the words of Claudian,

"Jam non ad culmina rerumInjustos crevisse queror; tolluntur in altum,Ut lapsu graviore ruant."Claudian, in Rufinum, Lib. i., v. 21.CHAPTER LXIV

Effects of Napoleon's return upon the Parisians – Congratulations and addresses by all the public Functionaries – Conspiracy of Mallet – very nearly successful – How at last defeated – The impression made by this event upon Buonaparte – Discussions with the Pope, who is brought to France, but remains inflexible – State of Affairs in Spain – Napoleon's great and successful exertions to recruit his Army – Guards of Honour – In the month of April, the army is raised to 350,000 men, independently of the troops left in garrison in Germany, and in Spain and Italy.

Upon the morning succeeding his return, which was like the sudden appearance of one dropped from the heavens, Paris resounded with the news; which had, such was the force of Napoleon's character, and the habits of subjection to which the Parisians were inured, the effect of giving a new impulse to the whole capital. If the impressions made by the twenty-ninth bulletin could not be effaced, they were carefully concealed. The grumblers suppressed their murmurs, which had begun to be alarming. The mourners dried their tears, or shed them in solitude. The safe return of Napoleon was a sufficient cure for the loss of 500,000 men, and served to assuage the sorrows of as many widows and orphans.237 The emperor convoked the Council of State. He spoke with apparent frankness of the misfortunes which had befallen his army, and imputed them all to the snow. – "All had gone well," he said; "Moscow was in our power – every obstacle was overcome – the conflagration of the city had produced no change on the flourishing condition of the French army; but winter has been productive of a general calamity, in consequence of which the army had sustained very great losses." One would have thought, from his mode of stating the matter, that the snow had surprised him in the midst of victory, and not in the course of a disastrous and inevitable retreat.

The Moniteur was at first silent on the news from Russia, and announced the advent of the Emperor as if he had returned from Fontainbleau; but after an interval of this apparent coldness, like the waters of a river in the thaw, accumulating behind, and at length precipitating themselves over, a barrier of ice, arose the general gratulation of the public functionaries, whose power and profit must stand or fall with the dominion of the Emperor, and whose voices alone were admitted to represent those of the people. The cities of Rome, Florence, Milan, Turin, Hamburgh, Amsterdam, Mayence, and whatever others there were of consequence in the empire, joined in the general asseveration, that the presence of the Emperor alone was all that was necessary to convert disquietude into happiness and tranquillity. The most exaggerated praise of Napoleon's great qualities, the most unlimited devotion to his service, the most implicit confidence in his wisdom, were the theme of these addresses. Their flattery was not only ill-timed, considering the great loss which the country had sustained; but it was so grossly exaggerated in some instances, as to throw ridicule even upon the high talents of the party to whom it was addressed, as daubers are often seen to make a ridiculous caricature of the finest original. In the few circles where criticism on these effusions of loyalty might be whispered, the authors of the addresses were compared to the duped devotee in Molière's comedy, who, instead of sympathizing in his wife's illness, and the general indisposition of his family, only rejoices to hear that Tartuffe is in admirable good health. Yet there were few even among these scoffers who would have dared to stay behind, had they been commanded to attend the Emperor to Notre Dame, that Te Deum might be celebrated for the safe return of Napoleon, though purchased by the total destruction of his great army.

CONSPIRACY OF MALLETBut it was amongst the public offices that the return of the Emperor so unexpectedly, produced the deepest sensation. They were accustomed to go on at a moderate rate with the ordinary routine of duty, while the Emperor was on any expedition; but his return had the sudden effect of the appearance of the master in the school, from which he had been a short time absent. All was bustle, alertness, exertion, and anticipation. On the present occasion, double diligence, or the show of it, was exerted; for all feared, and some with reason, that their conduct on a late event might have incurred the severe censure of the Emperor. We allude to the conspiracy of Mallet, a singular incident, the details of which we have omitted till now.

During Buonaparte's former periods of absence, the government of the interior of France, under the management of Cambacérès, went on in the ordinary course, as methodically, though not so actively, as when Napoleon was at the Tuileries; the system of administration was accurate, that of superintendence not less so. The obligations of the public functionaries were held as strict as those of military men. But during the length of Napoleon's absence on the Russian expedition, a plot was formed, which served to show how little firm was the hold which the system of the Imperial government had on the feelings of the nation, by what slight means its fall might be effected, and how small an interest a new revolution would have excited.238 It seemed that the Emperor's power showed stately and stable to the eye, like a tall pine-tree, which, while it spreads its shade broad around, and raises its head to heaven, cannot send its roots, like those of the oak, deep into the bowels of the earth, but, spreading them along the shallow surface, is liable to be overthrown by the first assault of the whirlwind.