Полная версия

Полная версияПолная версия:

Life of Napoleon Bonaparte. Volume IV

The Turks made a far better defence than had been anticipated; and though the events of war were at first unfavourable to them, yet at length the Grand Vizier obtained a victory before Routschouk, or at least gave the Russian general such a serious check as obliged him to raise the siege of that place. But the gleam of victory on the Turkish banners was of brief duration. They were attacked by the Russians in their intrenched camp, and defeated in a battle so sanguinary, that the vanquished army was almost annihilated.99 The Turks, however, continued to maintain the war, forgotten and neglected as they were by the Emperor of France, whose interest it chiefly was, considering his views against Russia, to have sustained them in their unequal struggle against that formidable power. In the meanwhile, hostilities languished, and negotiations were commenced; for the Russians were of course desirous, so soon as a war against France became a probable event, to close that with Turkey, which must keep engaged a very considerable army, at a time when all their forces were necessary to oppose the expected attack of Napoleon.

At this period, and so late as the 21st March, 1812, it seemed to occur all at once to Buonaparte's recollection, that it would be highly politic to maintain, or rather to renew, his league with a nation, of whom it was at the time most important to secure the confidence. His ambassador was directed to urge the Grand Signior in person to move towards the Danube, at the head of 100,000 men; in consideration of which, the French Emperor proposed not only to obtain possession for them of the two disputed provinces of Moldavia and Wallachia, but also to procure the restoration to the Porte of the Crimea.

This war-breathing message arrived too late, the Porte having adopted a specific line of policy. The splendid promises of France succeeded too abruptly to so many years of neglect, to obtain credit for sincerity. The envoys of England, with a dexterity which it has not been always their fortune to display, obtained a complete victory in diplomacy over those of France, and were able to impress on the Sublime Porte the belief, that though Russia was their natural enemy among European nations, yet a peace of some permanence might be secured with her, under the guarantee of England and Sweden; whereas, if Napoleon should altogether destroy Russia, the Turkish empire, of which he had already meditated the division, would be a measure no state could have influence to prevent, as, in subduing Russia, he would overcome the last terrestrial barrier to his absolute power. It gives no slight idea of the general terror and suspicion impressed by the very name of Napoleon, that a barbarous people like the Turks, who generally only comprehend so much of politics as lies straight before them, should have been able to understand that there was wisdom in giving peace on reasonable terms to an old and inveterate enemy, rather than, by assisting in his destruction, to contribute to the elevation of a power still more formidable, more ambitious, and less easily opposed. The peace of Bucharest was accordingly negotiated betwixt Russia and Turkey; of which we shall hereafter have occasion to speak.

Thus was France, on the approaching struggle, deprived of her two ancient allies, Sweden and Turkey. Prussia she brought to the field like a slave at her chariot-wheels; Denmark and Saxony in the character of allies, who were favoured so long as they were sufficiently subservient; and Austria, as a more equal confederate, but who had contrived to stipulate, that, in requital of an aid coldly and unwillingly granted, the French Emperor should tie himself down by engagements respecting Poland, which interfered with his using his influence over that country in the manner which would best have served his purposes. The result must lead to one of two conclusions. Either that Napoleon, confident in the immense preparations of his military force, disdained to enter into negotiations to obtain that assistance which he could not directly command, or else that his talents in politics were inferior to those which he displayed in military affairs.

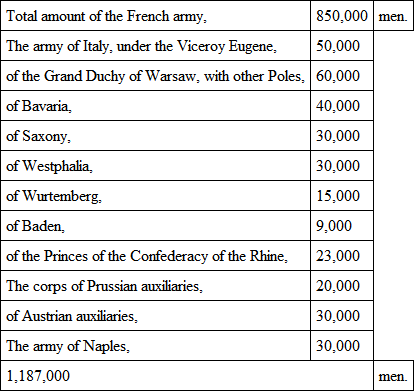

STATE OF THE ARMYIt is true, that if the numbers, and we may add the quality, of the army which France brought into the field on this momentous occasion, were alone to be considered, Napoleon might be excused for holding cheap the assistance which he might have derived from Sweden or the Porte. He had anticipated the conscription of 1811, and he now called out that of 1812; so that it became plain, that so long as Napoleon lived and warred, the conscription of the first class would be – not a conditional regulation, to be acted or not acted upon according to occasion – but a regular and never-to-be-remitted tax of eighty thousand men, annually levied, without distinction, on the youth of France. To the amount of these conscriptions for two years, were to be added the contingents of household kings, vassal princes, subjected republics – of two-thirds of Europe, in short, which were placed under Buonaparte's command. No such army had taken the field since the reign of Xerxes, supposing the exaggerated accounts of the Persian invasion to be admitted as historical. The head almost turns dizzy as we read the amount of their numbers.

The gross amount of the whole forces of the empire of France, and its dependencies and allies, is thus given by Boutourlin: —100

But to approximate the actual force, we must deduce from this total of 1,187,000, about 387,000 men, for those in the hospital, absent upon furlough, and for incomplete regiments. Still there remains the appalling balance of 800,000 men, ready to maintain the war; so that Buonaparte was enabled to detach an army to Russia greatly superior to what the Emperor Alexander could, without immense exertions, get under arms, and this without withdrawing any part of his forces from Spain.

Still, however, in calculating all the chances attending the eventful game on which so much was to be staked, and to encounter such attempts upon France as England might, by his absence, be tempted to make, Napoleon judged it prudent to have recourse to additional means of national defence, which might extend the duty of military service still more widely among his subjects than was effected even by the conscription. As the measure was never but in one particular brought into general activity, it may be treated of the more slightly. The system consisted in a levy of national guards, divided into three general classes – the Ban, the Second Ban, and Arriere-Ban; for Buonaparte loved to retain the phrases of the old feudal institutions. The First Ban was to contain all men, from twenty to twenty-six years, who had not been called to serve in the army. The Second Ban included all capable of bearing arms, from the age of twenty-six to that of forty. The Arriere-Ban comprehended all able-bodied men from forty to sixty. The levies from these classes were not to be sent beyond the frontiers of France, and were to be called out in succession, as the danger pressed. They were divided into cohorts of 1120 men each. But it was the essential part of this project, that it placed one hundred cohorts of the First Ban – (that is, upwards of 100,000 men, between twenty and twenty-six years) – at the immediate disposal of the minister of war. In short, it was a new form of conscription, with the advantage, to the recruits, of limited service.

The celebrated philosopher Count La Cepède, who, from his researches into natural history, as well as from the ready eloquence with which he could express the acquiescence of the Senate in whatever scheme was proposed by the Emperor, had acquired the title of King of Reptiles, had upon this occasion his usual task of justifying the Imperial measures. In this allotment of another mighty draught of the youth of France to the purposes of military service, at a time when only the unbounded ambition of Napoleon rendered such a measure necessary, he could discover nothing save a new and affecting proof of the Emperor's paternal regard for his subjects. The youths, he said, would be relieved by one-sixth part of a cohort at a time; and, being at an age when ardour of mind is united to strength of body, they would find in the exercise of arms rather salutary sport, and agreeable recreation, than painful labour or severe duty. Then the express prohibition to quit the frontiers would be, their parents might rest assured, an absolute check on the fiery and impetuous character of the French soldier, and prevent the young men from listening to their headlong courage, and rushing forward into distant fields of combat, which no doubt there might be otherwise reason to apprehend. All this sounded very well, but the time was not long ere the Senate removed their writ ne exeat regno, in the case of these hundred cohorts; and, whether hurried on by their own impetuous valour, or forced forward by command of their leaders, they were all engaged in foreign service, and marched off to distant and bloody fields, from which few of them had the good fortune to return.

CIUDAD RODRIGO – BADAJOSWhile the question of peace or war was yet trembling in the scales, news arrived from Spain that Lord Wellington had opened the campaign by an enterprise equally successfully conceived and daringly executed. Ciudad Rodrigo, which the French had greatly strengthened, was one of the keys of the frontier between Spain and Portugal. Lord Wellington had blockaded it, as we have seen, on the preceding year, but more with the purpose of compelling General Marmont to concentrate his forces for its relief, than with any hope of taking the place. But, in the beginning of January 1812, the French heard with surprise and alarm that the English army, suddenly put in motion, had opened trenches before Ciudad Rodrigo, and were battering in breach.

Marmont once more put his whole forces in motion, to prevent the fall of a place which was of the greatest consequence to both parties; and he had every reason to hope for success, since Ciudad Rodrigo, before its fortifications had been improved by the French, had held out against Massena for more than a month, though his army consisted of 100,000 men. But, in the present instance, within ten days from the opening of the siege, the place was carried by storm, almost under the very eyes of the experienced general who was advancing to its relief, and who had no alternative but to retire again to cantonments, and ponder upon the skill and activity which seemed of a sudden to have inspired the British forces.

Lord Wellington was none of those generals who think that an advantage, or a victory gained, is sufficient work for one campaign. The French were hardly reconciled to the loss of Ciudad Rodrigo, so extraordinary did it appear to them, when Badajos was invested, a much stronger place, which had stood a siege of thirty-six days against the French in the year 1811, although the defences were then much weaker, and the place commanded by an officer of no talent, and dubious fidelity. It was now, with incomprehensible celerity, battered, breached, stormed, and taken, within twelve days after the opening of the trenches. Two French Marshals had in vain interfered to prevent this catastrophe. Marmont made an unsuccessful attempt upon Ciudad Rodrigo, and assumed the air of pushing into Portugal; but no sooner did he learn the fall of the place, than he commenced his retreat from Castel-Branco. Soult, who had advanced rapidly to relieve Badajos, was in the act, it is said, of informing a circle of his officers that it was the commands of the Emperor – commands never under any circumstances to be disobeyed – that Badajos should be relieved, when an officer, who had been sent forward to reconnoitre, interrupted the shouts of "Vive l'Empereur!" with the equally dispiriting and incredible information, that the English colours were flying on the walls.

These two brilliant achievements were not only of great importance by their influence on the events of the campaign, but still more so as they indicated that our military operations had assumed an entirely new character, and that the British soldiers, as now conducted, had not only the advantage of their own strength of body and natural courage, not only the benefit of the resources copiously supplied by the wealthy nation to whom they belonged, but also, as began to be generally allowed, an undoubted superiority in military art and science. The objects of the campaign were admirably chosen, for the exertion to be made was calculated with a degree of accuracy which dazzled and bewildered the enemy; and though the loss incurred in their attainment was very considerable, yet it was not in proportion to the much greater advantages attained by success.

Badajos fell on the 7th April; and on the 18th of that month, an overture of pacific tendency was made by the French Government to that of Britain. It is not unlikely that Buonaparte, on beholding his best commanders completely out-generalled before Ciudad Rodrigo and Badajos, might foresee in this inauspicious commencement the long train of defeat and disaster which befell the French in the campaign of 1812, the events of which could not have failed to give liberty to Spain, had Spain, or rather had her Government, been united among themselves, and cordial in supporting their allies.

It might be Lord Wellington's successes, or the lingering anxiety to avoid a war involving so many contingencies as that of Russia; or it might be a desire to impress the French public that he was always disposed towards peace, that induced Napoleon to direct the Duke of Bassano101 to write a letter to Lord Castlereagh, proposing that the integrity and independence of Spain should be guaranteed under the present reigning dynasty; that Portugal should remain under the rule of the Princes of Braganza; Sicily under that of Ferdinand; and Naples under Murat; each nation, in this manner, retaining possession of that which the other had not been able to wrench from them by force of war. Lord Castlereagh immediately replied, that if the reign of King Joseph were meant by the phrase, "the dynasty actually reigning," he must answer explicitly, that England's engagements to Ferdinand VII. and the Cortes presently governing Spain, rendered her acknowledging him impossible.102

The correspondence went no farther.103 The nature of the overture served to show the tenacity of Buonaparte's character, who, in treating for peace, would yield nothing save that which the fate of war had actually placed beyond his reach; and expected the British to yield up to him the very kingdom of Spain, whose fate depended upon the bloody arbitrement of the sword. It also manifested the insincerity with which he could use words to mislead those who treated with him. He had in many instances, some of which we have quoted, laid it down as a sacred principle, that princes of his blood, called to reign over foreign states, should remain still the subjects of France and vassals of its Emperor, whose interest they were bound to prefer on all occasions to that of the countries they were called to govern. Upon these grounds he had compelled the abdication of King Louis of Holland; and how was it possible for him to expect to receive credit, when he proposed to render Spain independent under Joseph, whose authority was unable to control even the French marshals who acted in his name?

HOSTILE PREPARATIONSThis feeble effort towards a general peace having altogether miscarried, it became subject of consideration, whether the approaching breach betwixt the two great empires could yet be prevented. The most active preparations for war were taking place on both sides. Those of Russia were defensive; but she mustered great armies on the Niemen, as if in expectation of an assault; while France was rapidly pouring troops into Prussia, and into the grand duchy of Warsaw, and assuming those positions most favourable for invading the Russian frontier. Yet amid preparations for war, made on such an immense scale as Europe had never before witnessed, there seemed to be a lingering wish on the part of both Sovereigns, even at this late hour, to avoid the conflict. This indeed might have been easily done, had there been on the part of Napoleon a hearty desire to make peace, instead of what could only be termed a degree of hesitation to commence hostilities. In fact, the original causes of quarrel were already settled, or, what is the same thing, principles had been fixed, on which their arrangement might be easily adjusted. Yet still the preparations for invading Russia became more and more evident – the purpose was distinctly expressed in the treaty between France and Prussia; and the war did not appear the less certain that the causes of it seemed to be in a great measure abandoned. The anxiety of Alexander was therefore diverted from the source of the dispute to its important consequences; and he became most naturally more solicitous about having the French troops withdrawn from the frontiers of Poland, than about the cause that originally brought them there.

Accordingly, Prince Kourakin, the Russian plenipotentiary, had orders to communicate to the Duke of Bassano his master's ultimatum. The grounds of arrangement proposed by the Czar were, the evacuation of Prussia and Pomerania by the French troops; a diminution of the garrison of Dantzic; and an amicable arrangement of the dispute between Napoleon and Alexander. On these conditions, which, in fact, were no more than necessary to assure Russia of France's peaceable intentions, the Czar agreed to place his commerce upon a system of licenses as conducted in France; to introduce the clauses necessary to protect the French trade; and farther, to use his influence with the Duke of Oldenburg, to obtain his consent to accept some reasonable indemnification for the territory which had been so summarily annexed to France.

In looking back at this document, it appears to possess as much the character of moderation, and even of deference, as could be expected from the chief of a great empire. His demand that France, unless it were her determined purpose to make war, should withdraw the armies which threatened the Russian frontier, seems no more than common sense or prudence would commend. Yet this condition was made by Napoleon, however unreasonably, the direct cause of hostilities.

The person, in a private brawl, who should say to an angry and violent opponent, "Sheathe your sword, or at least lower its point, and I will accommodate with you, on your own terms, the original cause of quarrel," would surely not be considered as having given him any affront, or other cause for instant violence. Yet Buonaparte, in nearly the same situation, resented as an unatonable offence, the demand that he should withdraw his armies from a position, where they could have no other purpose save to overawe Russia. The demand, he said, was insolent; he was not accustomed to be addressed in that style, nor to regulate his movements by the commands of a foreign sovereign. The Russian ambassador received his passports; and the unreasonable caprice of Napoleon, which considered an overture towards an amicable treaty as a gross offence, because it summoned him to desist from his menacing attitude, led to the death of millions, and the irretrievable downfall of the most extraordinary empire which the world had ever seen. On the 9th May, 1812, Buonaparte left Paris; the Russian ambassador had his passports for departure two days later.

ROYAL FESTIVITIESUpon his former military expeditions, it had been usual for Napoleon to join his army suddenly, and with a slender attendance; but on the present occasion he assumed a style of splendour and dignity becoming one, who might, if any earthly sovereign ever could, have assumed the title of King of Kings. Dresden was appointed as a mutual rendezvous for all the Kings, Dominations, Princes, Dukes, and dependent royalties of every description, who were subordinate to Napoleon, or hoped for good or evil at his hands. The Emperor of Austria, with his Empress, met his mighty son-in-law upon this occasion, and the city was crowded with princes of the most ancient birth, as well as with others who claimed still higher rank, as belonging to the family of Napoleon. The King of Prussia also was present, neither a willing nor a welcome guest, unless so far as his attendance was necessary to swell the victor's triumph. Melancholy in heart and in looks, he wandered through the gay and splendid scenes, a mourner rather than a reveller. But fate had amends in store, for a prince whose course, in times of unparalleled distress, had been marked by courage and patriotism.104

Amidst all these dignitaries, no one interested the public so much as he, for whom, and by whom the assembly was collected; the wonderful being who could have governed the world, but could not rule his own restless mind. When visible, Napoleon was the principal figure of the group; when absent, every eye was on the door, expecting his entrance.105 He was chiefly employed in business in his cabinet, while the other crowned personages (to whom, indeed, he left but little to do) were wandering abroad in quest of amusement. The feasts and banquets, as well as the assemblies of the royal personages and their suites, after the theatrical representations, were almost all at Napoleon's expense, and were conducted in a style of splendour, which made those attempted by any of the other potentates seem mean and paltry.

The youthful Empress had her share of these days of grandeur. "The reign of Maria Louisa," said her husband, when at St. Helena, "has been very short, but she had much to make her enjoy it. She had the world at her feet." Her superior magnificence in dress and ornaments, gave her a great pre-eminence over her mother-in-law, the Empress of Austria, betwixt whom and Maria Louisa there seems to have existed something of that petty feud, which is apt to divide such relations in private life. To make the Austrian Empress some amends, Buonaparte informs us, that she often visited her daughter-in-law's toilette, and seldom went back without receiving some marks of her munificence.106 Perhaps we may say of this information, as Napoleon says of something else, that an Emperor should not have known these circumstances, or at least should not have told them. The truth is, Buonaparte did not love the Empress of Austria; and though he represents that high personage as showing him much attention, the dislike was mutual. The daughter of the Duke of Modena had not forgot her father's sufferings by the campaigns of Italy.107

In a short time, however, the active spirit of Napoleon led him to tire of a scene, where his vanity might for a time be gratified, but which soon palled on his imagination as empty and frivolous. He sent for De Pradt, the Archbishop of Malines, whose talents he desired to employ as ambassador at Warsaw, and in a singular style of diplomacy, thus gave him his commission: "I am about to make a trial of you. You may believe I did not send for you here to say mass" (which ceremony the Archbishop had performed that morning.) "You must keep a great establishment; have an eye to the women, their influence is essential in that country. You know Poland; you have read Rulhières. For me, I go to beat the Russians; time is flying; we must have all over by the end of September; perhaps we are even already too late. I am tired to death here; I have been here eight days playing the courtier to the Empress of Austria." He then threw out indistinct hints of compelling Austria to quit her hold on Galicia, and accept an indemnification in Illyria, or otherwise remain without any. As to Prussia, he avowed his intention, when the war was over, to ruin her completely, and to strip her of Silesia. "I am on my way to Moscow," he added. "Two battles there will do the business. I will burn Thoula; the Emperor Alexander will come on his knees, and then is Russia disarmed. All is ready, and only waits my presence. Moscow is the heart of their empire; besides, I make war at the expense of the blood of the Poles. I will leave fifty thousand of my Frenchmen in Poland. I will convert Dantzic into another Gibraltar. I will give fifty millions a-year in subsidies to the Poles. I can afford the expense. Without Russia be included, the Continental System would be mere folly. Spain costs me very dear; without her I should be master of the world; but when I am so, my son will have nothing to do but to keep his place, and it does not require to be very clever to do that. Go, take your instructions from Maret."108