Полная версия:

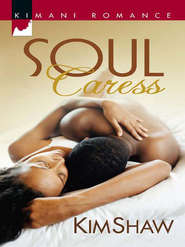

Soul Caress

Genuine concern echoed in his words, as if he felt somehow responsible for her comfort and care. She wondered if he were a hospital worker.

Kennedy felt a strong hand under the bend of her knee. As the metal bar above the gurney from which her broken leg was suspended was adjusted, bringing her leg about ten degrees lower, she concentrated on the softness of the wide palm against her skin. The warmth from his touch remained on her leg after he removed his hand.

“Godspeed on your recovery, Miss,” the voice said, just as her gurney began rolling off of the elevator.

The sincerity in his tone struck her, yet still she offered no response. She felt the urge to say something to the man but was still so far from being sociable that she couldn’t make herself talk. She was thankful, however, because she did feel more comfortable after his adjustment. His voice stayed with her, its soothing timbre ironically finding its way into her soul when the pain was at its worst.

Five days after the accident Kennedy was removed from the intensive care unit and transplanted into a private room. The fire in her skin had all but vanished by then and slowly she had begun to feel sensations other than the raw pain that had been her constant companion since the accident. The nurses and orderlies settled her into her new room with all of the machines and tubes still connected. When they left, her head and eyes still bandaged and taped shut, Kennedy believed that once again she was alone. She had grown accustomed to not being able to see anything through the thick bandages and had begun to learn to listen for sounds of life around her. Suddenly, she heard breathing and turned her head sharply in the direction from which it came.

“Why didn’t I think to bring a camera? Darling, you look positively wretched.”

The voice came from a corner of the room.

“Skyy?” Kennedy cried.

“It’s me…in the flesh,” Skyy answered, moving to Kennedy’s bedside and plopping down on the bed next to her.

She took Kennedy’s non-bandaged right hand in hers.

“I would have been here sooner, sweetheart, but would you believe there was not one empty seat on one stinking plane until last night?”

Skyy leaned down and pressed cool lips against the side of Kennedy’s cheek.

“How are you?”

“I’m feeling a lot better than I look, I’m sure,” Kennedy answered weakly.

“Mmm, hmm. Well, my dear, judging from the slur in your voice, I’d say you’ve made friends with the Percocet fairy. That’s probably why you’re feeling so good.” Skyy giggled.

“Actually, it’s Vicodin now and we are on a first name basis,” Kennedy said, a pained smile pushing through her lips.

Skyy and Kennedy had been best friends since seventh grade at the all-girls boarding school they’d attended. They had been more like sisters than friends ever since they’d been paired together as lab partners in biology class. In a social circle that consisted of the Who’s Who in Young Black America, Skyy was the most real person Kennedy had ever met.

Unlike most of Kennedy’s other friends, and herself for that matter, Skyy was not part of a legacy of doctors, lawyers and social debutantes. Her father was a self-made man who had made friends with the right people, and clawed his way into a brotherhood of the moneyed folks of North Carolina. No matter how hard he tried, however, there was lingering in him, his wife and their only child, an element of roughness of the Southside of Chicago, from which they had fled as soon as he could afford it when Skyy was twelve years old.

While Skyy adapted to their new lifestyle of Bentleys and private schools, she never accepted or adopted the arrogance of the wealthy. When she and Kennedy first started hanging out together, Kennedy had attempted to draw her into her circle of friends, who were the prettiest, most popular of the girls, both black and white, in school.

Seated in the cafeteria enjoying chef-quality meals of broiled salmon and steamed asparagus tips, the girls were whispering and teetering over one of the new additions to the school, a girl who was there on scholarship, whose hand-me-down outfits and GAP jeans made her stick out like a sore thumb amongst the rest of the Lacoste-wearing, diamond-studded young girls. Skyy had remained quiet, studying the girl who sat alone, eating her lunch beneath the cloud of adolescent snubs. All of a sudden, Skyy rose from her seat, picked up her tray and marched deliberately across the cafeteria. She stopped at the girl’s table, said something to her and then sat down. Kennedy and her crew were stunned and after that day, Kennedy had been told in no uncertain terms that she had to make a choice. It was Skyy or them. Today, she turned to face her friend’s voice, glad at the choice she’d made.

“Where are your folks?” Skyy asked, tossing her hair over her shoulder.

Kennedy wished she could see Skyy, wondering what transformation her friend had gone through during her latest jaunt overseas. Skyy had been in Italy for the past three months. The firm she worked with, Samage Designs, had landed one exclusive hotel or restaurant after the other and Skyy’s fresh eye and youthful approach to design was a large part of the equation. Travel was the thing that, once bitten, Skyy had yet to be able to shake. She loved packing up and hitting the road and for her, the farther the distance, the better. Before Italy, she’d been home in North Carolina for only a couple of months, having spent the prior nine months in Japan designing and implementing the construction of a five-star hotel in Tokyo.

Each time she came back to the United States, Skyy was a different person. Once, there was a short, fiery red hairstyle, that, despite the shocking effect it had, actually looked fantastic on her. Another time, after a visit to India, she came home with her head shaved bald. These days, her hair having grown back to her shoulders, she rocked a permed layered style, colored jet-black. Her copper-penny brown face, with its slanted eyes and pixie nose, was sun-kissed and vibrant, bespeaking her strict vegan diet and rigorous exercise regimen.

“They left yesterday. Daddy had to get back to his patients and Mother, well, you know Mother. She can’t stand living out of a suitcase,” Kennedy laughed.

She didn’t need to let on to Skyy that she was glad that her parents had gone back home. Having them around worrying over her was as intense as the physical discomfort she was in, if not more. Skyy knew better than anyone how trying Kennedy’s parents could be.

“What about Maddie? What’s she up to?” Skyy asked.

“You know Madison…nothing new there. She was here, too, and was fighting with Mother as usual. Once I assured them that I was going to be fine, she hopped in her car and headed up to New York to visit Liza Penning.”

After the young Daniels sisters had kicked Liza’s butt all over the summer camp that year, Madison and Liza had become best friends. Liza was now a stand-up comedienne living in New York City.

“I’m sure Elmira was thrilled about that,” Skyy laughed.

“Yeah, well, what can she do? Madison is a grown woman now.”

“Yeah, grown and still living at home, sponging off of Mommy and Daddy. I don’t know why your parents don’t just cut her off. I bet you that would make her straighten up and fly right.”

Kennedy considered Skyy’s words for a moment, and one moment was all it took for her to dismiss them. First, there was no way her parents would ever cut Madison off. The Daniels would walk through hell with gasoline cans strapped to their backs before they ever allowed one of their own to have to make do without or depend on others for their survival. Secondly, as much as Madison rebelled against them, she and Elmira were so much alike that not accepting her and her behaviors would be the equivalent of her mother turning against herself. No, Madison had yet to find that thing, if it existed, that would push her parents to the breaking point, although she’d come very close once or twice.

“She promised that she’d stop back in to check on me by the weekend. If you’re still here, maybe you can talk some sense into her.”

Both Kennedy and Skyy erupted with much-needed laughter at the absurdity of that one.

“Yeah, well I’ll still be here by the weekend, but I damned sure won’t waste my breath talking to your sister about anything other than shoes and men.” Skyy smirked.

Skyy stayed in town for the remainder of the week, spending the days seated by Kennedy’s bedside, reading to her. They finished the Eric Jerome Dickey novel Kennedy had been planning to read before the accident, as well as a half a dozen gossip magazines and the latest issues of Ebony and Essence magazines. They listened to the news on television every evening and the daily talk shows in the afternoon. Skyy fed Kennedy the nutritious, yet tasteless hospital meals that were delivered three times a day, and snuck in cheesecake and other sweets in between meals. It was also Skyy’s job to deliver the twice-daily medical updates to Elmira and Joseph, who threatened to fly back up to D.C. in a moment’s notice. At Kennedy’s request, Skyy kept them at bay with glowing reports of the patient’s progress.

Kennedy was, in fact, improving. The bruises on her skin had begun to scab over and peel away. She could now move her left arm without feeling any pain, although she was somewhat limited by the full arm cast extending from the center of her right hand up to her elbow.

Her shattered right knee was still held immobile, sealed tightly in a cast made of fiberglass and hanging from a trapeze above her bed. Skyy gave Kennedy a French pedicure, after sponging and applying lotion to her size nine feet. She did the fingers on both of her hands to match, trimming and shaping the nails first. Finally, she made her way to Kennedy’s hair, using a sponge and the aloe-scented latherless shampoo she’d purchased at a local beauty supply store. She combed the once glowing mane, freeing it of its tangles and dry patches where various liquids had settled since the accident. Carefully avoiding the bandages that were wound around the nape of her neck and across her forehead and eyes, Skyy parted Kennedy’s hair into small sections and wiped the shampoo through. Next, she brushed it until it began to shine again, braided it into a long, tight French braid and wrapped a ponytail holder securely around the end.

She helped Kennedy change out of the ugly blue hospital gown that had been placed on her damaged body by the nurses into a pale pink, Victoria’s Secret nightshirt made of pure silk.

“Now, you’re beginning to look human again,” she remarked when she had finished her spa treatment.

“What do you mean?” Kennedy exclaimed.

“Girl, I hate to say this about my one and only best friend, but you were extremely torn up when I got here. Crusty, ashy and wild don’t even begin to describe the way you looked,” Skyy replied.

As much as Skyy rejected the attitude of the bourgeois black class to which her parents wholeheartedly subscribed, she did appreciate the finer things in life. She was a woman of taste. The standards she set were high, but they were her own. She believed a woman should look her best at all times, but rejected the belief that good looks could only be achieved with a lot of money.

“Oh, great Skyy. Way to kick a sister when she’s down,” Kennedy lamented.

The hardest part of the past week had been the fact that she didn’t have the use of her eyes. She couldn’t wait until the bandages were taken off so she could get a good look at herself—her body and her injuries. From touching her face, she could tell that it was no longer swollen and with the exception of the gash on her forehead, which the doctor had told her had required twelve stitches to close, there were no other injuries to her face.

Skyy had told her that the bruises to her arms and legs, as well as the scratches that had come from the broken glass, were all healing well. Despite this, she longed to see herself for herself. She was impatient for the moment she could look into a mirror, stare into her own eyes and confirm that she was really all right. She needed to see for herself that she had really made it through the worse ordeal of her entire life. However, she’d have to wait a few days longer. The ophthalmologist had conferred with Dr. Moskowitz, reviewing the initial X-rays and optical images taken of her eyes. They agreed that Kennedy’s eyes simply would need time to heal and that no medical interventions were warranted.

As promised, Madison returned to D.C., although it was Sunday afternoon when she finally made it back down from her jaunt in New York City. A mere ten minutes in her presence and Skyy shook her head dismally, excusing herself from the room. The next day, with Madison on the road again, headed home to North Carolina, Skyy finally voiced what had been eating away at her brain.

“Kennedy, I hate to be the bearer of bad news, but your sister is headed for a fall. Now, let me know if I’m overstepping here, and I’ll just shut my mouth.”

“Of course you can say whatever you have to say, Skyy. You know you’re family. And, if I don’t like it, I’ll just curse you out…like family.” Kennedy smiled.

“I just don’t understand why your parents allow that girl to rip and run, not working or going to school…doing whatever the hell she wants. She looks like crap and she dresses like a five-dollar hooker.”

Kennedy winced at Skyy’s words, but every part of her told her that they were true. Skyy was the one person in this world who she could count on unequivocally to tell her the truth, no matter whether she wanted to hear it or not.

“Does she get high?”

Skyy’s question was raised in a tone that suggested that she already had her own beliefs on the matter.

“I think she’s dabbled a little in the past, but I don’t think it’s heavy. I mean, you know that Liza girl she hangs out with and the rest of those spoiled rich kids playing artists up there in New York they associate with.”

“Well, she looks like she’s doing more than dibbing and dabbing. Look, girl, I know you’ve got enough to deal with here, getting yourself healed and whatnot. However, the next time you go home to Carolina, I suggest you sit that girl down and have a talk with her. She needs to get her butt back into school or something constructive and in a hurry. She’s too old to play the rebellious teen role. It isn’t cute anymore.”

Madison had dropped out of Spelman College after her first year. This had been especially shocking since she had begged her parents to allow her to go there, although they had expected her to follow in Kennedy’s footsteps and attend Princeton.

They’d relented, unable to deny the fact that although Spelman was a historically black university—and in their minds accessible to all types of people who were of questionable backgrounds—it had graduated countless successful African-American women of high caliber and social standing. When Madison had returned home after her freshman year, having maintained a low B average, and announced that she wasn’t going back, it was puzzling. It eventually occurred to Kennedy that the only reason she’d wanted to attend Spelman in the first place was to piss her parents off and now that the thrill of that was gone, she was ready to make a fast exit.

Madison had spent the past three years finding herself, whatever that meant. From Kennedy’s standpoint, all she’d managed to find since leaving Spelman was more and more trouble for her parents to bail her out of.

First it was the apartment she begged them to rent for her, and then was summarily kicked out of after breaching the complex’s rules with wild parties and unregistered overnight guests. Then there was the time she was detained in a jail cell in Mexico after getting into a bar fight in Cozumel, Mexico, with the daughter of an elected official. Her father had paid dearly to make that little indiscretion disappear. The girl blew through more money than a category five tornado through Kansas in the height of storm season.

Kennedy agreed with Skyy, promising that as soon as she’d recovered enough to travel, she’d head home to spend some quality time with her baby sister. In the meantime, she had to concentrate on getting herself out of that hospital bed. The sooner she got on her feet, the better off she’d be. When Skyy finally left, planning to make a quick pit stop in North Carolina to see her parents before returning to her work—and the distinguished Italian gentleman she was dating—in Rome, it was a tearful farewell. Each woman realized how much they relied on their friendship and the truth of the matter was that they had come very close to losing that, had Kennedy’s accident been worse than it was. Skyy left with the promise that she’d be back in another couple of months to check on her girl.

Chapter 4

Kennedy spent the days convalescing in solitude. The thought of having visitors, other than her parents, her sister and Skyy, sent her into an unexplainable panic attack. She received a dozen bouquets of flowers from coworkers at Morgan Stanley, from her parents’ bridge partners, the Thompsons, and from her condo neighbor, Victoria, with whom she occasionally shared a cup of morning coffee over their adjoining balconies. The cards, the flowers, the phone calls all wishing her well, were appreciated, but after only a few days, she could not take any more. She wanted to be left alone, to wallow in self-pity at the unfairness of it all. While Kennedy was not the type of person who stayed down for long, she felt like she deserved some quality time in melancholyville. She reasoned that after a good, uninterrupted dose of the why me’s, she could concentrate on the business of getting better and healing her body and mind.

She had the phone, which her parents had turned on in her room, turned off again and asked that visitors be refused by the hospital staff. Anyone who called the nurses’ station to inquire about her recovery was directed to call her parents. In the days that passed after Skyy left, Kennedy replayed the accident over and over in her mind, kicking herself for not having had her brakes checked weeks before when they’d first begun squeaking. She questioned why she had been driving so fast, headed home to an empty apartment and a book. She tried her hardest not to cry, not wanting to soak the bandages that still covered her wounded eyes. Yet the morose thoughts that clouded her mind brought with them a deluge of tears that struggled against her sealed eyelids.

The nurses and doctors checked in on her regularly, poking, prodding, changing bandages and recording her progress. Two weeks to the day after the accident, Dr. Moskowitz, conferring with ophthalmologist Dr. Pitcher, informed her that it was time to remove the bandages that sealed her eyes and to perform a comprehensive examination of her vision.

Both doctors had cautioned that there might be some damage to her vision, although they remained optimistic that the scratches that were observed immediately after the accident were superficial. Kennedy’s excitement and anxiety were at odds within as she prepared herself for the unveiling. Her hopes remained for the best, as she was more than ready to get out of the hospital and get back to her life.

Kennedy sat impatiently in the cushioned chair while Dr. Moskowitz slowly snipped away the bandages round her head. As he unwound the strips of gauze, he talked to her in a soothing voice, explaining what he was doing each step of the way. As the layers of gauze diminished, Kennedy anxiously awaited a glimmer of light or her first sightings. Anything that came into view would be welcomed after residing in darkness for so many agonizing days.

“We taped your eyelids down to help with the healing,” Dr. Moskowitz stated as if in answer to Kennedy’s thoughts.

Finally, when all of the bandages had been removed, Dr. Moskowitz prepared to peel back the thick adhesive that kept Kennedy’s eyes closed.

“Before I take away the tape, I just want you to be prepared for changes in your vision. There may be blurriness or distortion. The corneas may not be completely healed yet. I don’t want you to be alarmed. Just relax and describe to me what you are able to see as things come into focus.”

The tissue around her eye sockets felt sore and Dr. Moskowitz reassured her that this was due to the fact that the lids had been held shut and bandaged for so long. There had been no damage to the bone or tissue surrounding her eyes. Kennedy took a deep breath as Dr. Moskowitz glided a wet piece of gauze across both of her eyelids to moisten the adhesive. Then he quickly pulled away the tape, freeing first the left eye and then the right. Kennedy took another deep breath to steady her racing heartbeat and slowly opened her eyes. The ever-present darkness that had surrounded her for the past two weeks remained.

“Dr. Moskowitz?” she called, her voice a whisper. “Dr. Moskowitz?”

“Yes, Kennedy. I’m right here. What can you see?” he asked.

“Nothing. Dr. Moskowitz, why can’t I see you? Everything is dark and…blurry.”

Kennedy reached both hands outward, her palms slapping against the doctor’s chest. Her breathing became rapid as panic seized her heart. Her fingers groped until she made contact with the doctor’s lab coat. She clutched the fabric harshly, pulling at it.

“Kennedy, Kennedy. Calm down, please. I need to examine you,” Dr. Moskowitz said.

He pulled a small penlight from his breast pocket, shining it into Kennedy’s eyes, first the left and then the right. Her pupils remained wide and unseeing, save for blurred shadows of objects around her. Not one thing was discernable to her eyes and there existed only the most minimal snatches of light.

“Kennedy, it is too early to determine anything concrete about your vision. You have to remain optimistic. These things sometimes take more time and patience than we’d like them to.”

Further examination showed that the deceleration of her brain during the crash had caused Post Trauma Vision Syndrome. The prognosis was mixed and it was uncertain if Kennedy’s sight would ever return.

Tears pooled in Kennedy’s brown eyes instantaneously, engulfing her sockets and sliding down her honey-brown cheeks. Dr. Moskowitz suspended his examination and attempted to comfort her with words that fell upon deaf ears. She could not hear anything nor could her mind register a coherent thought. She had awakened from the singularly most harrowing incident of her life and despite the pain and anguish, had sincerely believed that with time, things would get back to normal. Now, the realization that nothing would ever again be normal for her smacked her in the face and she crumbled from the weight of the blow.

Chapter 5

“Bonjour,” Nurse Crosby beamed as she burst through the door to Kennedy’s private room.

Her shoes squeaked as she crossed the carpeted floor, bustling toward the window. Nurse Crosby snatched the curtains back in one quick motion.

“There. Let’s let a little sunshine in here,” she quipped. “That’s better, isn’t it?”

Kennedy did not respond nor did she move. She wanted to ask what difference it made whether the room was sunlit or not. It wasn’t as if she could see it. Curtains open or closed, the room was still a dungeon devoid of color and light. She didn’t say this, however. There was no reason to annihilate Nurse Crosby’s cheery disposition with her sour one. Besides, she’d rather sulk silently in her stew of despondency.

“It’s a beautiful day out there, Ms. Daniels. What do you say I help you get ready for your walk?” Nurse Crosby asked, as she pulled back the blanket that covered Kennedy’s lower body.

Kennedy leaned forward abruptly.

“Walk? I’m not going for a walk,” she replied.

Obviously, Nurse Crosby had had one too many cups of caffeine this morning. Either that or Kennedy surmised that she was as blind as Kennedy was if she couldn’t see that, not only was Kennedy’s leg up in a trapeze with a cast from foot to thigh, but that she could not see her hand in front of her face. There would be no walking today.