Полная версия:

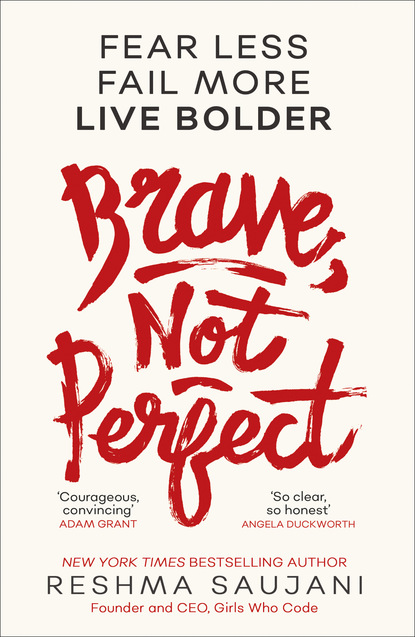

Brave, Not Perfect

I wrote this book because I believe that every single one of us can learn to be brave enough to achieve our greatest dreams. Whether that dream is to be a multimillionaire, to climb Mt. Everest, or just to live without the fear of judgment hanging over our heads all the time, it all starts to become possible when we override our perfect-girl programming and retrain ourselves to be brave.

No more silencing or holding ourselves back, or teaching our daughters to do the same. It’s time to stop this paradigm in its tracks. And just in case you’re thinking that bravery is a luxury reserved for the 1 percent, let me assure you: I’ve spoken to women across a wide range of backgrounds and economic circumstances, and this is a problem that affects us all. My goal is to create a far-reaching movement of women that will inspire all women to embrace imperfection, so they can build a better life and a better world. No more letting opportunities go by, no more dimming our brilliance, no more deferring our dreams. It’s time to stop pursuing perfection and start chasing bravery instead.

Anaïs Nin wrote, “Life shrinks or expands in proportion to one’s courage.” If this is true—and I believe that it is—then courage is the key to living the biggest life we can create for ourselves. I am writing this book because I believe every woman deserves a shot at breaking free from the perfectionor-bust chokehold and living the joyful, audacious life she was meant to lead.

1

Sugar and Spice and Everything Nice

Sixteen-year-old Erica is a shining star. The daughter of two prominent professors, she is the vice president of her class with an impeccable grade point average. Her report card is peppered with praise from her teachers about her diligence and what a joy she is to have in class. She volunteers twice a month at a local hospital. At the end of sophomore year, she was voted “Best Smile” by her classmates, and her friends will tell you she’s the sweetest person they know.

Beneath that bright smile, though, things aren’t quite as sunny. If you open Erica’s journal, you’ll read about how she feels like it’s her full-time job to be perfect in order to make everyone else happy. You’ll learn that she works to the point of exhaustion every night and all weekend to get all A’s and please her parents and teachers; disappointing them is just about the worst thing she can imagine. Once, because of an accidental scheduling mistake, she had to back out of a debate competition at school because it conflicted with a volunteer trip she’d committed to go on with her church; she was so hysterical that her teacher was going to “hate her” that she literally made herself sick.

Erica despises volunteering at the hospital (don’t even get her started on emptying the bedpans . . . ) but sticks with it because her guidance counselor said it would look good on her college applications. Even though she desperately wanted to try out for cheerleading team because she thought it looked like fun, she didn’t, because her friends told her the jumps were really hard to learn and the last thing she wanted to do was make an idiot of herself. Truth be told, she doesn’t really even like most of her friends, who can be mean and catty, but she just quietly goes along with what they say and do because it’s too scary to imagine doing otherwise.

Like so many girls, Erica is hardwired to please everyone, play it safe, and avoid any hint of failure at all costs.

I know this story because today, Erica is forty-two and a good friend of mine. She is still supersweet with a dazzling smile—and still a prisoner of her own perfectionism. A successful political consultant with no kids, she works until after midnight most nights to impress her colleagues and overdeliver for her clients. Every time I see her she looks fabulously put together; she’s that friend who always says just the right thing, always sends just the right gift or note, and is always on time. But just like her sixteen-year-old self, she’ll only reveal privately that she still feels strangled by the constant need to please everyone. I asked her recently what she would do if she didn’t care what anyone else thought. She immediately ticked off a list of goals and dreams she wished she had the guts to go after but wouldn’t dare, ranging from telling her biggest client that she disagrees with his strategies to moving out of the city and having a child on her own.

Our culture has shaped generations of perfect girls like Erica who grow up to be women afraid to take a chance. Afraid of speaking their minds, of making bold choices, of owning and celebrating their achievements, and of living the life they want to live, without constantly seeking outside approval. In other words: afraid of being brave.

From the time they are babies, girls absorb hundreds of micromessages each day telling them that they should be nice, polite, and polished. Adoring parents and caretakers dress them impeccably in color-coordinated outfits (with matching bows) and tell them how pretty they look. They are praised mightily for being A students and for being helpful, polite, and accommodating and are chided (however lovingly) for being messy, assertive, or loud.

Well-meaning parents and educators guide girls toward activities and endeavors they are good at so they can shine, and steer them away from ones they might find frustrating, or worse, at which they could fail. It’s understandable because we see girls as vulnerable and fragile, we instinctively want to protect them from harm and judgment.

Our boys, on the other hand, are given freedom to roam, explore, get dirty, fall down, and yes, fail—all in the name of teaching them to “man up” as early as possible. Even now, for all our social progress, people get a little uncomfortable if a boy is too hesitant, cautious, or vulnerable—let alone sheds a tear. I see this even with my own twenty-first-century feminist husband, who regularly roughhouses with my son to “toughen him up” and tells me to let him cry it out when he’s screaming at night. I once asked him if he would do the same if Shaan were a girl and he immediately responded, “Of course not.”

Of course, these beliefs don’t vanish just because we grow up. If anything, the pressure on women to be perfect ramps up as life gets more complex. We go from trying to be perfect students and daughters to perfect professionals, perfect girlfriends, perfect wives, and perfect mommies, hitting the marks we’re supposed to and wondering why we’re overwhelmed, frustrated, and unhappy. Something is just missing. We did everything right, so what went wrong?

When you’re writing a book about women and perfectionism, you start to see it everywhere. In airports, at coffee shops, at conferences, at the nail salon . . . pretty much anywhere I went, I’d strike up a conversation on the topic and women would invariably sigh or roll their eyes knowingly, nod or laugh in recognition, or get sad as they shared a personal story. They’d tell me how their daily lives are ruled by a relentless inner drive to do everything flawlessly, from curating their Instagram feed to pleasing their partner (or struggling to find the “perfect” partner) to raising all-star kids who are also well adjusted (and who go straight from a year of breastfeeding to eating homemade, organic meals); from staying in shape and looking “good for their age” to striving ceaselessly to be the best in the office, in their congregation or volunteer group or community, in Soul-Cycle and CrossFit classes, and everywhere else.

So many women of all ages opened up to me about unfulfilled life dreams or ambitions they harbor because they’re too afraid to act on them. Regardless of ethnicity, profession, economic circumstances, or what town they call home, I was struck by how many of their experiences were the same. You’ll hear from many of them throughout this book.

But first, I want to show you all the ways the drive to be perfect got ingrained in us. What follows in this chapter is a glimpse into how our perfectionism took root as girls, how it shaped us as women, and how it colored every choice we’ve made along the way. We need to understand how we got here so we can thoughtfully navigate our way out. This is the beginning of the road map that leads us off a path of regret and onto one where we fully express who and what we most want to be.

The Origins of Perfectionism

Where along the way did we trade in our confidence and courage for approval and acceptance? And why?

The categorization of girls as pleasant and agreeable starts almost as soon as they’re born. Instinctually, whether we realize it or not, we ascribe certain expectations to infants we see in pink or blue; babies in pink are all sugar and spice, babies in blue are tough little men. But it turns out that we even make assumptions when there are no other telltale signs of gender. One study showed that when infants are dressed in a neutral color, adults tend to identify the ones who appear upset or angry as boys, and those they described as nice and happy as girls. The training begins before we’re even out of onesies.

In girls, the drive to be perfect shows up and bravery shuts down somewhere around age eight—right around the time when our inner critic shows up. You know the one I’m talking about: it’s that nitpicking voice in your head that tells you every which way you aren’t as good as others . . . that you blew it . . . that you should feel guilty or ashamed . . . that you fucking suck (I don’t know about yours, but my inner critic can be a bit harsh).

Catherine Steiner-Adair is a renowned clinical psychologist, school consultant, and research associate at Harvard Medical School. She works with hundreds of girls and young women across the country and has seen firsthand how devastating perfectionism can be.

At around the age of eight, she says, kids start to see that ability and agility matter. “That’s the age when girls start to develop different interests, and they want to bond with others who do what they like to do. Along with that awareness of differences comes an inner sense of who and what is better.”

This is also the age in which kids begin to be graded, ranked, and told their scores—whether it’s in soccer, math, or music, Steiner-Adair explains. “If you’re told you’re not as good, it requires a great deal of courage and self-esteem to try something. This sets the stage for getting a C means you’re bad at it, and you don’t like it. That feeds the lack of courage.”

As girls get older, their radars sharpen. Around this age, they start to tune in when their moms compare themselves to others (“I wish I looked like that in jeans”) or talk about other girls or women critically (“She should not be wearing that”). Suddenly they’re caught up in this dynamic of comparison, and naturally redirect their radar inward to determine where they fall on the spectrum of pretty or not, bright or average, unpopular or adored.

These impulses are so deeply ingrained in us as adults and parents that we don’t realize how much we inadvertently model them for our girls. Catherine shared a story from her own life that brought the point home. When her daughter was in third grade, she and some classmates overheard one mom say to another girl, “You have such pretty hair.” Some of the girls stopped dead in their tracks and furrowed their brows as if to wonder, So is my hair pretty or ugly? And so it begins.

The Overpowering Need to Please

Like most women, I was taught from an early age to be helpful, obedient, and care for other people’s needs, even to put them above my own. When my parents told me not to date until I was sixteen, I didn’t. When they said no makeup, or showing cleavage, or staying out past 10 p.m., I obeyed. I complied at all times with the behavior my family expected of me. In our Indian household, one greeted elders by touching their feet as a sign of respect; if I came home from school with a friend and found an older auntie there having tea, I would never dream of disrespecting my parents by not doing it, although I was mortified in front of my friend. At family dinners, my sister and I set and cleared the table, never questioning why our male cousins didn’t have to take a turn. Even though I would have much rather been outside playing with my friends, I always agreed to babysit my neighbor’s (bratty) kids. That’s just what helpful girls my age did.

Thus began my lifelong mission to be the perfect daughter, the perfect girlfriend, the perfect employee, the perfect mom. In this I know I’m not alone. We go from yes-girls to yes-women, caught in a never-ending cycle of constantly having to prove our worth to others—and to ourselves—by being selfless, accommodating, and agreeable.

A great example of how powerful the people-pleasing impulse can be comes from an experiment about lemonade. Yes, lemonade. ABC News, with the help of psychologist Campbell Leaper from the University of California, gave groups of boys and girls a glass of lemonade that was objectively awful (they added salt instead of sugar) and asked how they liked it. The boys immediately said, “Eeech . . . this tastes disgusting!” All the girls, however, politely drank it, even choked it down. Only when the researchers pushed and asked the girls why they hadn’t told them the lemonade was terrible did the girls admit that they hadn’t wanted to make the researchers feel bad.

The need to please people often shows up in the way girls scramble to give the “right” answer. Ask a girl her opinion on a topic and she’ll do a quick calculation. Should she say what the teacher/parent/friend/boy is looking for her to say, or should she reveal what she genuinely thinks and believes? It usually comes down to whichever she thinks will be more likely to secure approval or affection.

Girls are also far more likely than boys to say yes to requests even when they really want (and even need) to say no. Remember, being accommodating has been baked into their emotional DNA. When I ask girls what they do if a friend asks them to do her a favor they really don’t want or have time to do, nearly all say they would do it anyway. Why? Hallie, a freckle-faced fourteen-year-old, neatly summed it up with a “duh, that’s so obvious” shrug: “No one wants their friends to think she’s a bitch. I mean, no one.”

The internal pressure to say yes only gets stronger as we grow up. Like Dina, who works long hours as an attorney but somehow felt guilted into agreeing to be her son’s class parent. So many of us give our time, attention, maybe even money, to people or causes that are not a priority to us because we don’t want to hurt anyone’s feelings (mostly, though, because we don’t want them to think badly of us).

Boys, and the men they become, rarely feel this way. Janet, a forty-four-year-old manager at a clothing store, cringes anytime she reads an email that her husband, a general contractor, sends for work because she thinks his directness sounds harsh. He bluntly asks for what he needs or states his opinion, never softens critical feedback, and signs his emails without any salutations. No “best wishes” or even “thanks.” When she once suggested he soften the tone of an email to a vendor he worked with so as to not piss him off, he told her, “It’s not my job to be liked. It’s my job to get my point across.”

She, on the other hand, peppers her emails to her boss and coworkers with friendly lead-ins, praise, and, occasionally, a smiley face emoji. She reads over every email at least three times, editing and reediting it before she hits send. “My husband thinks I’m being neurotic when I do that,” Janet told me. “I think I’m being thorough. But if I’m being really honest, I’d say I’m being cautious so I don’t annoy or offend anyone.”

I work with an executive coach who tells me all the time that being liked is overrated. She does not say this to the über-successful male CEOs she coaches; she doesn’t have to. After all, their role models are men like Steve Jobs and Jeff Bezos who are notorious for not being people pleasers, so they don’t give a damn whether they’re liked or not.

Despite my coach’s urgings, I do worry about being liked. Running for office, especially in New York City, I built a pretty tough skin when it comes to public criticism. But on a day-to-day level, I care whether my team likes me. I care a lot. I want them to think I’m the most amazing boss they’ve ever had—which makes giving them critical feedback really hard. I do it, because I know I have to be the CEO, but ugh. In my personal life, I get completely twisted up inside if I have a disagreement with a friend or if I sense my parents or husband are upset with me. I’ve definitely spent nights worrying about how a colleague, an acquaintance—even a complete stranger!—may have interpreted something I’ve said, and I’ve soft-pedaled way too many times when I really should have ripped someone a new one.

Just yesterday a guy cut in front of me in line while I was buying a sandwich and even though I was pissed, I didn’t say a word because I didn’t want to be rude—and this was someone I didn’t even know and would likely never see again. And I too have been guilty of saying nice things even when I secretly think the exact opposite, so as to not offend (hello, salty lemonade). Haven’t we all?

The result of all this toxic people pleasing is that your whole life can quickly become about what others think, and very little about what you genuinely want, need, and believe—let alone what you deserve. We’ve become conditioned to compromise and shrink ourselves in order to be liked. The problem is, when you work so hard to get everyone to like you, you very often end up not liking yourself so much. But once you learn to be brave enough to stop worrying about pleasing everyone else and put yourself first (which you will!), that’s when you become the empowered author of your own life.

The “Softer” Sex

One sunny Saturday morning in late May, I sat on a bench in a playground in downtown Manhattan watching my husband, Nihal, and our then sixteen-month-old son, Shaan, play. Or, rather, I was watching my son bop from the monkey bars to the jungle gym and back again while Nihal stood a decent distance away and watched. Shaan’s shirt was smeared with strawberry ice cream and his nose was filled with boogers, but he didn’t care—and neither did I. Still new to the whole vertical coordination thing, Shaan toppled over a couple of times as he waddled from one end of the playground to another; each time, rather than run to his rescue, Nihal calmly waited for him to get up and keep going. At one point, I looked over and saw him coaxing Shaan, who was a little scared, down the big slide. “You can do this . . . you’re a big boy . . . you’re not afraid!”

Nearby, a few older boys were play-fighting using sticks as swords and chasing one another. Lots of happy hollering and a sea of dirty, scabby knees and elbows: a classic case of grade-school boys at play.

Meanwhile, over at the sandbox, five girls who looked to be around three years old were playing quietly. No ice-cream-smeared shirts or booger-encrusted noses there. Wearing cute coordinated outfits, they took turns scooping piles of sand to make a pretend cake, while their moms watched intently from a few feet away. In a ten-minute span, three of the five moms jumped up from their perches and climbed into the sandbox—one to straighten her daughter’s headband and another to reprimand her daughter for being “rude” by taking the shovel from another girl. The third mom rushed to her daughter’s aid after her sand “cake” fell over and hurriedly helped her daughter rebuild it while making soothing noises and wiping the tears from the girl’s face. When the cake was fixed, the little girl smiled and her mom beamed with pride, “There’s my happy girl!”

You can’t make this stuff up.

Nearly everything I’d read, researched, witnessed, and interviewed experts about over the past year was playing out right in front of me. Go figure: a classic illustration of how boys are socialized to be brave and girls to be perfect, right here on a little asphalt playground less than ten minutes from my apartment.

At the same time we’re applauding our girls for being nice, polite, and perfect, we are also telling them in not-so-subtle ways that bravery is the domain of boys. What I saw that day on the playground reminded me of another scene I’d witnessed just a few months earlier in Shaan’s swim class. Parents were encouraging their timid sons to “be tough,” and shouting with glee when their boys jumped into the deep end. If one of the little girls in the class was afraid to jump in, however, her fears were met with soft, reassuring coos: “It’s okay, honey . . . just take my hand . . . you don’t have to get your face wet.” This one really made no sense to me; I mean, how do you go swimming without getting wet?

This isn’t just casual observation on my part. Studies show that parents provide much more hands-on assistance and words of caution to their daughters, while their sons are given encouragement and directives from afar and then left to tackle physical challenges on their own. We start with protecting girls physically, and the coddling continues on from there.

So many of these patterns are perpetuated because as parents, we’re punished socially for violating them. A woman named Kelly told me a story about a group excursion she took to Oregon with her son and daughter, along with several other families. After taking a mountain bike ride, they hiked up a cliff where the rocks create a natural slide into the water. Their guide, Billy, helped all the kids out onto the rocks and offered them a push down the slide. The boys all went right away, but Kelly’s usually courageous daughter was nervous. Instead of encouraging her the way he had done with the boys—that is, by just giving them a little shove—Billy helped her off the cliff and gently assured her that she didn’t have to go if she didn’t want.

Meanwhile, Kelly, knowing that her daughter is usually fearless, was hollering from the bottom, “Go, Ellie!” When it became clear that Billy wasn’t going to give her a nudge as he did for the boys, she screamed up the cliff, “JUST PUSH HER!” Everyone around was horrified. “Every adult on the tour gave me the side-eye,” she remembers. “They didn’t even try to hide their judgment about how I was encouraging someone to push my daughter to be brave. We’re not supposed to do that to our daughters.”

The belief that boys are tough and resilient while girls are vulnerable and need to be protected is both deeply and widely held. In 2017, the World Health Organization released a groundbreaking study done in partnership with Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Across fifteen countries, from the United States to China to Nigeria, these very gender stereotypes proved to be universal and enduring; and the study found that children buy into this myth at a very early age.

This “girls are softer” mentality extends beyond the playground, often straight into the classroom. One problem is what girls focus on when they’re given difficult feedback. When girls are told they got a wrong answer or made a mistake, all they hear is condemnation, which sears like a flaming arrow straight through the heart. They go straight from “I did this wrong” to “I suck” to “I give up,” rarely stopping at “Oh, I see how I could do this better next time.”

The bigger problem, however, is how adults respond. To spare the girls’ fragile feelings, we naturally temper anything that sounds too critical. More protection, more soft-pedaling, more steering girls to what’s “safe,” more feeding the self-fulfilling prophecy of girls as vulnerable. But if they are constantly shielded from any sharp edges, how can they be expected to build any resilience to avoid falling apart later in life if (more like when) they run up against real criticism or setbacks?