Полная версия

Полная версияПолная версия:

Ten Thousand a-Year. Volume 3

The more immediate object of his anxieties, was to conceal as far as possible his connection with the various joint-stock speculations, into which he had entered with a wild and feverish eagerness to realize a rapid fortune. He had already withdrawn from one or two with which he had been only for a brief time, and secretly, connected—not, however, until he had realized no inconsiderable sum by his judicious but somewhat unscrupulous operations. He was also anxious, if practicable, to extricate Lord Dreddlington, at the proper conjuncture, with as little damage as possible to his Lordship's fortune or character: for his Lordship's countenance and good offices were becoming of greater consequence to Mr. Gammon than ever. It was true that he possessed information—I mean that concerning Titmouse's birth and true position—which he considered would, whenever he thought fit to avail himself of it, give him an absolute mastery over the unhappy peer for the rest of his life; but he felt that it would be a critical and dreadful experiment, and not to be attempted but in the very last resort. He would sometimes gaze at the unconscious earl, and speculate in a sort of revery upon the possible effects attending the dreaded disclosure, till he would give a sort of inward start as he realized the fearful and irretrievable extent to which he had committed himself. He shuddered also to think that he was, moreover, in a measure, at the mercy of Titmouse himself—who, in some mad moment of drunkenness or desperation, or of pique or revenge, might disclose the fatal secret, and precipitate upon him, when least prepared for them, all its long-dreaded consequences. The slender faculties of Lord Dreddlington had been for months in a state of novel and grateful excitement, through the occupation afforded them by his connection with the fashionable modes of commercial enterprise—joint-stock companies, the fortunate members of which got rich they scarcely knew how. It seemed as though certain persons had but to acquire a nominal interest in some great transaction of this sort, to find it pouring wealth into their coffers, as if by magic; and it was thus that Lord Dreddlington, among others, found himself quietly realizing very considerable sums of money, without apparent risk or exertion—his movements being skilfully guided by Gammon, and one or two others, who, while they treated him as a mere instrument to aid in effecting their own purposes in deluding the public, yet contrived to impress him with the flattering notion that he was, in a masterly manner, directing their course of procedure, and richly entitled to their deference and gratitude. 'T was, indeed, ecstasy to poor old Lord Dreddlington to behold his name, from time to time, glittering in the van—himself figuring away as a chief patron—a prime mover—in some vast and lucrative undertaking, which, almost from the first moment of its projection, attracted the notice and confidence of the moneyed classes, and became productive to its originators! Many attempts were made by his brother peers, and those who once had considerable influence over him, to open his eyes to the very questionable nature of the concerns to which he was so freely lending the sanction of his name and personal interference; but his pride and obstinacy caused him to turn a deaf ear to their suggestions; and the skilful and delicious flatteries of Mr. Gammon and others, seconded by the substantial fruits of his fancied skill and energy, urged him on from step to step, till he became one of the most active and constant in his interference with the concerns of one or two great speculations, such as have been mentioned in a former part of this history, and from which he looked forward to realizing, at no very distant day, the most resplendent results. Never, in fact, had one man obtained over another a more complete mastery, than had Mr. Gammon over the Earl of Dreddlington; at whose exclusive table he was a frequent guest, and thereby obtained opportunities of acquiring the good-will of one or two other persons of the earl's intellectual status and calibre.

His Lordship was sitting in his library (his table covered with letters and papers) one morning, with a newspaper—the Morning Growl—lying in his lap, and a certain portion of the aforesaid newspaper he had read over several times with exquisite satisfaction. He had, late on the preceding evening, returned from his seat in Hertfordshire, whither he had been suddenly called on business, early in the morning; so that it was not until the time at which he is now presented to the reader, that his Lordship had had an opportunity of perusing what was now affording him such gratification; viz. a brief, but highly flattering report of a splendid whitebait dinner which had been given to him the day before at Blackwall, by a party of some thirty gentlemen, who were, inter nos, most adroit and successful traders upon that inexhaustible capital, public credulity, as founders, managers, and directors, of various popular joint-stock companies; and the progress of which, in public estimation, had been materially accelerated by the countenance of so distinguished a nobleman as the Right Hon. the Earl of Dreddlington, G. C. B., &c. &c. &c.13 When his Lordship's carriage—containing himself, in evening dress, and wearing his red ribbon, and one or two foreign orders, and also his son-in-law, the member for Yatton, who was dressed in the highest style of fashionable elegance—drew up opposite the doorway of the hotel, he was received, on alighting, by several of those who had assembled to do him honor, in the same sort of flattering and reverential manner which you may conceive would be exhibited by a party of great East India directors, on the occasion of their giving a banquet to a newly-appointed Governor-General of India! Covers had been laid for thirty-five, and the entertainment was in all respects of the most sumptuous description—every way worthy of the entertainers and their distinguished guest. Not far from the earl sat Mr. Gammon. Methinks I see now his gentlemanly figure—his dark-blue coat, white waistcoat, and simple black stock—his calm smile, his keen watchful eye, his well-developed forehead, suggesting to you a capability of the highest kind of intellectual action. There was a subdued cheerfulness in his manner, which was bland and fascinating as ever; and towards the great man of the day, he exhibited such a marked air of deference as was, indeed, to the object of it, most delicious and seductive. The earl soon mounted into the seventh heaven of delight; he had never experienced anything of this sort before; he felt glorified—for such qualities were attributed to him in the after-dinner speeches, as even he had not before imagined the existence of in himself; his ears were ravished with the sound of his own praises. He was infinitely more intoxicated by the magnificent compliments which he received, than by the very unusual, but still not excessive, quantity of champagne which he had half unconsciously taken during dinner; the combined effect of them being to produce a state of delightful excitement which he had never known before. Mr. Titmouse, M. P., also came in for his share of laudation, and made—said the report in the Morning Growl—a brief but very spirited speech, in return for the compliment of his health being proposed. At length, it being time to think of returning to town, his Lordship withdrew, Sir Sharper Bubble, (the chairman,) and others, attending him bareheaded to his carriage, which, his Lordship and Titmouse having entered, drove off amid the bows and courteous inclinations of the gentlemen standing upon and around the steps. Titmouse almost immediately fell asleep, overpowered by the prodigious quantity of wine which he had swallowed; and thus left the earl, who was himself in a much more buoyant humor than was usual with him, to revel in the recollection of the homage which he had been receiving. Now, this was the affair, of which a very flourishing though brief account (privately paid for by the gentleman who sent it) appeared in the Morning Growl, with a most magnificent speech of his Lordship's about free trade, and the expansive principles of commercial enterprise, and so forth: 't was true, that the earl had no recollection of having either meditated the delivery of any such speech, or of having actually delivered it—but he might have done so for all that, and possibly did. He read over the whole account several times, as I have already said; and at the moment of his being presented to the reader, sitting in his easy-chair, and with the newspaper in his lap, he was in a very delightful state of feeling. He secretly owned to himself that he was not entirely undeserving of the compliments which had been paid to him. Considerably advanced though he was in life, he was consciously developing energies commensurate with the exigencies which called for their display—energies which had long lain dormant for want of such opportunities. What practical tact and judgment he felt conscious of exhibiting, while directing the experienced energies of mercantile men and capitalists! How proud and delighted was he at the share he was taking in steering the commercial enterprise of the country into proper quarters, and to proper objects; and, moreover, while he was thus benefiting his country, he was also sensibly augmenting his own private revenue. In his place in the House of Lords, also, he displayed a wonderful energy, and manifested surprising interest in all mercantile questions started there. He was, consequently, nominated one of a committee (into the appointment of which he and one or two others like him had teased and worried their Lordships) to inquire into the best mode of facilitating the formation, and extending the operations, of Joint-Stock Companies; and asked at least four times as many questions of the witnesses called before them, as any other member of the committee. He also began to feel still loftier aspirations. His Lordship was not without hopes that the declining health of Sir Miserable Muddle, the president of the Board of Trade, would soon open a prospect for his Lordship's accession to office, as the successor of that enlightened statesman; feeling conscious that the mercantile part of the community would look with great approbation upon so satisfactory an appointment, and that thereby the king's government would be materially strengthened. As for matter of a more directly business character, I may mention that his Lordship was taking active measures towards organizing a company for the purchase of the Isle of Dogs, and working the invaluable mines of copper, lead, and coal which lay underneath. These and other matters fully occupied his Lordship's attention, and kept him from morning to night in a pleasurable state of excitement and activity. Still he had his drawbacks. The inexorable premier continued to turn a deaf ear to all his solicitations for a marquisate—till he began to entertain the notion of transferring his support to the opposition; and, in fact, he resolved upon doing so, if another session should have elapsed without his receiving the legitimate reward of his steadfast adherence to the Liberal cause. Then again he became more and more sensible that Lady Cecilia was not happy in her union with Mr. Titmouse, and that his conduct was not calculated to make her so; in fact, his Lordship began to suspect that there was a total incompatibility of tempers and dispositions, which would inevitably force on a separation—under existing circumstances a painful step, and evidently unadvisable. His Lordship's numerous inquiries of Mr. Gammon as to the state of Mr. Titmouse's property, met occasionally with unsatisfactory, and (as any one of clearer head than his Lordship would have seen) most inconsistent answers. Mr. Titmouse's extravagant expenditure was a matter of notoriety; the earl himself had been once or twice compelled to come forward, in order to assist in relieving his son-in-law's house from executions; and he repeatedly reasoned and remonstrated with Mr. Titmouse on the impropriety of many parts of his conduct—Titmouse generally acknowledging, with much appearance of compunction and sincerity, that the earl had too much ground for complaint, and protesting that he meant to change altogether one of these days. Indeed, matters would soon have been brought to a crisis between the earl and Titmouse, had not the former been so constantly immersed in business, as to prevent his mind from dwelling upon the various instances of Titmouse's misconduct which from time to time came under his notice. The condition of Lady Cecilia was one which gave the earl anxiety and interest. She was enceinte; and the prospect which this afforded the earl, of the family honors continuing in a course of direct descent, gave him unspeakable satisfaction. Thus is it, in short, that no one's cup is destitute of some ingredients of bitterness or of happiness; that the wheat and the tares—happiness and anxiety—grow up together. The above will suffice to indicate the course taken by his Lordship's thoughts on the present occasion. He sat back in his chair in a sort of revery; having laid down his paper, and placed his gold spectacles on the little stand beside him, where lay also his massive old gold repeater. The Morning Growl of that morning was very late, owing to the arrival of foreign news; but it was brought in to his Lordship just as he was beginning to open his letters. These his Lordship laid aside for a moment, in order to skim over the contents of his paper; on which he had not been long engaged, before his eye lit upon a paragraph which gave him a dreadful shock, blanching his cheek, and throwing him into an universal tremor. He read it over several times, almost doubting whether he could be reading correctly. It is possible that the experienced reader may not be taken as much by surprise as was the Earl of Dreddlington; but the intelligence conveyed by the paragraph in question was simply this—that the Artificial Rain Company had, so to speak, suddenly evaporated!—and that this result had been precipitated by the astounding discovery in the City, in the preceding afternoon, that the managing director of the Company had bolted with all the available funds of the society—and who should this be but the gentleman who had presided so ably the evening but one before, over the Blackwall dinner to his Lordship, viz. Sir Sharper Bubble!!! The plain fact was, that that worthy had at that very time completed all arrangements necessary for taking the very decisive step on which he had determined; and within an hour's time of handing the Earl of Dreddlington to his carriage, in the way that has been described, had slipped into a boat moored by the water side, and got safely on board a fine brig bound for America, just as she was hauling up anchor, and spreading forth her canvas before a strong steady west wind, which was at that moment bearing him, under the name of Mr. Snooks, rapidly away from the artificial and unsatisfactory state of things which prevailed in the Old World, to a new one, where he hoped there would not exist such impediments in the way of extended commercial enterprise. As soon as the earl had a little recovered from the agitation into which this announcement had thrown him, he hastily rang his bell, and ordered his carriage to be got instantly in readiness. Having put the newspaper into his pocket, he was soon on his way, at a great speed, towards the Poultry, in the City, where was the office of the Company, with the faintest glimmer of a hope that there might be some mistake about the matter. Ordering his servant to let him out the instant that the carriage drew up, the earl, not allowing his servant to anticipate him, got down and rang the bell, the outer door being closed, although it was now twelve o'clock. The words "Artificial Rain Company" still shone in gilt letters half a foot long, on the green blind of the window. But all was—still—deserted—dry as Gideon's fleece! An old woman presently answered his summons. She said she believed the business was given up; and there had been a good many gentlemen inquiring about it—that he was welcome to go in—but there was nobody in except her and a little child. With an air of inconceivable agitation, his Lordship went into the lower offices. All was silent; no clerks, no servants, no porters or messengers; no books, or prospectuses, or writing materials. "I've just given everything a good dusting, sir," said she to the earl, at the same wiping off a little dust with the corner of her apron, which had escaped her. Then the earl went up-stairs into the "Board Room." There, also, all was silent and deserted, and very clean and in good order. There was the green baize-covered table, at which he had often sat, presiding over the enlightened deliberations of the directors! The earl gazed in silent stupor about him.

"They say it's a blow-up, sir," quoth the old woman. "But I should think it's rather sudden! There's been several here has looked as much struck as you, sir!" This recalled the earl to his senses, and, without uttering a word, he descended the stairs. "Beg pardon, sir—but could you tell me who I'm to look to for taking care of the place? I can't find out the gentleman as sent for me"–

"My good woman," replied the earl, faintly, hastening from the horrid scene, "I know nothing about it;" and, stepping into his carriage, he ordered it to drive on to Lombard Street, to the late Company's bankers. As soon as he had, with a little indistinctness arising from his agitation, mentioned the words "Artificial Rain"–

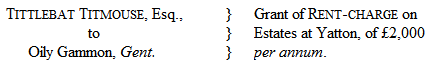

"Account closed!" was the brief matter-of-fact answer, given in a business-like and peremptory tone, the speaker immediately attending to some one else. The earl was too much flustered to observe a knowing wink interchanged among the clerks behind, as soon as they had caught the words "Artificial Rain Company!"—The earl, with increasing trepidation, re-entered his carriage, and ordered it to be driven to the office of Messrs. Quirk, Gammon, and Snap. There he arrived in a trice; but, being informed that Mr. Gammon had not yet come, and would probably be found at his chambers in Thavies' Inn, the horses' heads were forthwith turned, and within a few minutes' time the carriage had drawn up opposite to the entrance to Thavies' Inn—where the earl had never been before. Without sending his servant on beforehand to inquire, his Lordship immediately alighted, and soon found out the staircase where were Mr. Gammon's private apartments, on the first floor. The words "Mr. Gammon" were painted in white letters over the door, the outer one being open. His Lordship's rather hasty summons was answered by Mr. Gammon's laundress, a tidy middle-aged woman, who lived in the chambers, and informed the earl, that if he wished to see Mr. Gammon, he had better step in and wait for a minute or two—as Mr. Gammon had only just gone to the stationer's, a little way off, and said he should be back in a minute or two. In went the earl and sat down in Mr. Gammon's sitting-room. It was a fair-sized room, neatly furnished, more for use than show. A plain deal bookcase, stretching over the whole of one side of the apartment, was filled with books, and beside it, and opposite to the fireplace, was the door of Mr. Gammon's bedroom—which, being open, appeared as though it had not been yet set to rights since Mr. Gammon had slept in it. He had not, in fact, risen as early as usual that morning. The earl sat down, having removed his hat; and in placing it upon the table, his eye lit upon an object, which suggested to him a new source of amazement and alarm. It was a freshly executed parchment conveyance, folded up in the usual way, about a foot square in size; and as the earl sat down, his eye could scarcely fail to read the superscription, in large round hand, which was turned full towards him, and, in short, ran thus:—

This almost stopped the earl's breath. With trembling hands he put on his spectacles, to assure himself that he read correctly; and with a face overspread with dismay—almost unconscious of what he was doing—was gazing intensely at the writing, holding the parchment in his hands; and while thus absorbed, Mr. Gammon entered, having darted across the inn, and sprung up-stairs with lightning speed, the instant that his eye had caught Lord Dreddlington's equipage standing opposite to the inn. He had instantly recollected having left on the table the deed in question, which had been executed by Titmouse only the evening before; and little anticipated that, of all persons upon earth, Lord Dreddlington would be the first whose eye would light upon it. 'T was, perhaps, somewhat indiscreet to leave it there; but it was in Gammon's own private residence—where he had very few visitors, especially at that time of the day—and he had intended only a momentary absence, having gone out on the impulse of a sudden suggestion. See the result!

"My Lord Dreddlington!" exclaimed Gammon, breathless with haste and agitation, the instant he saw his worst apprehensions fulfilled. The earl looked up at him, as it were mechanically, over his glasses, without moving, or attempting to speak.

"I—I—beg your Lordship's pardon!" he added quickly and sternly, advancing towards Lord Dreddlington. "Pardon me, but surely your Lordship cannot be aware of the liberty you are taking—in looking at my private papers!"—and with an eager and not over-ceremonious hand, he took the conveyance out of the unresisting grasp of his noble visitor.

"Sir—Mr. Gammon!"—at length exclaimed the earl, in a faltering voice—"what is the meaning of that?" pointing with a tremulous finger to the conveyance which Mr. Gammon held in his hand.

"What is it? A private—a strictly private document of mine, my Lord"—replied Gammon, with breathless impetuosity, his eye flashing fury, and his face having become deadly pale—"one with which your Lordship has no more concern than your footman—one which I surely might have fancied safe from intrusive eyes in my own private residence—one which I am confounded—yes, confounded! my Lord, at finding that you could for an instant allow yourself—consider yourself warranted in even looking at—prying into—and much less presuming to ask questions concerning it!" He held the parchment all this while tightly grasped in his hands; his appearance and manner might have overpowered a man of stronger nerves than the Earl of Dreddlington. On him, however, it appeared to produce no impression—his faculties seeming quite absorbed with the discovery he had just made, and he simply inquired, without moving from his chair—

"Is it a fact, sir, that you have a rent-charge of two thousand a-year upon my son-in-law's property at Yatton?"

"I deny peremptorily your Lordship's right to ask me a single question arising out of information obtained in such a dis—I mean such an unprecedented manner!" answered Gammon, vehemently.

"Two thousand a-year, sir!—out of my son-in-law's property?" repeated the earl, with a kind of bewildered incredulity.

"I cannot comprehend your Lordship's conduct in attempting neither to justify what you have done, nor apologize for it," said Gammon, endeavoring to speak calmly; and at the same time depositing the conveyance in a large iron safe, and then locking the door of it, Lord Dreddlington, the while, eying his movements in silence.

"Mr. Gammon, I must and will have this matter explained; depend upon it, I will have it looked into and thoroughly sifted," at length said Lord Dreddlington, with returning self-possession, as Gammon observed—

"Can your Lordship derive any right to information from me, out of an act of your Lordship's which no honorable mind—nay, if your Lordship insists on my making myself understood—I will say, an act which no gentleman would resort to"–The earl rose from his chair with calmness and dignity.

"What your notions of honorable or gentlemanly conduct may happen to be, sir," said the old peer, drawing himself up to his full height, and speaking with his usual deliberation, "it may not be worth my while to inquire; but let me tell you, sir"–

"My Lord, I beg your Lordship's forgiveness—I have certainly been hurried by my excitement into expressions which I would gladly withdraw."

"Hear me, sir," replied the earl, with a composure which, under the circumstances, was wonderful; "it is the first time in my life that any one has presumed to speak to me in such a manner, and to use such language; and I will neither forget it, sir, nor forgive it."