Полная версия

Полная версияThe Literary Remains of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Volume 3

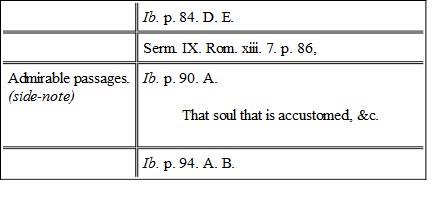

Ib. p. 66. A.

Some of the later authors in the Roman Church … have noted (in several of the Fathers) some inclinations towards that opinion, that the devil retaining still his faculty of free-will, is therefore capable of repentance, and so of benefit by this coming of Christ.

If this be assumed, – namely, the free-will of the devil, – as a consequence would indeed follow his capability of repenting, and the possibility that he may repent. But then he is no longer what we mean by the devil; he is no longer the evil spirit, but simply a wicked soul.

Ib. p. 68. C.

As though God had said Qui sum, my name is I am; yet in truth it is Qui ero, my name is I shall be.

Nay, I will or shall be in that I will to be. I am that only one who is self-originant, causa sui, whose will must be contemplated as antecedent in idea to or deeper than his own co-eternal being. But 'antecedent,' 'deeper,' &c. are mere vocabula impropria, words of accommodation, that may suggest the idea to a mind purified from the intrusive phantoms of space and time, but falsify and extinguish the truth, if taken as adequate exponents.

Ib. p. 69. C.

We affirm that it is not only as impious and irreligious a thing, but as senseless and as absurd a thing, to deny that the Son of God hath redeemed the world, as to deny that God hath created the world.

A bold but a true saying. The man who, cannot see the redemptive agency in the creation has but a dim apprehension of the creative power.

Ib. D. E. p. 70. A.

These paragraphs exhibit a noble instance of giving importance to the single words of a text, each word by itself a pregnant text. Here, too, lies the excellence, the imitable, but alas! unimitated, excellence of our divines from Elizabeth to William III.

Ib. D.

O, that our clergy did but know and see that their tithes and glebes belong to them as officers and functionaries of the nationalty, – as clerks, and not exclusively as theologians, and not at all as ministers of the Gospel; – but that they are likewise ministers of the Church of Christ, and that their claims and the powers of that Church are no more alienated or affected by their being at the same time the established clergy, than they are by the common coincidence of being justices of the peace, or heirs to an estate, or stockholders!35 The Romish divines placed the Church above the Scriptures; our present divines give it no place at all.

But Donne and his great contemporaries had not yet learnt to be afraid of announcing and enforcing the claims of the Church, distinct from, and coordinate with, the Scriptures. This is one evil consequence, though most un-necessarily so, of the union of the Church of Christ with the national Church, and of the claims of the Christian pastor and preacher with the legal and constitutional rights and revenues of the officers of the national clerisy. Our clergymen in thinking of their legal rights, forget those rights of theirs which depend on no human law at all.

Ib. p. 71. A.

This is the difference between God's mercy and his judgments, that sometimes his judgments may he plural, complicated, enwrapped in one another; but his mercies are always so, and cannot be otherwise.

A just sentiment beautifully expressed.

Ib. C.

Whereas the Christian religion is, as Gregory Nazianzen says, simplex et nuda, nisi prave in artem difficillimam converteretur: it is a plain, an easy, a perspicuous truth.

A religion of ideas, spiritual truths, or truth-powers, – not of notions and conceptions, the manufacture of the understanding, – is therefore simplex et nuda, that is, immediate; like the clear blue heaven of Italy, deep and transparent, an ocean unfathomable in its depth, and yet ground all the way. Still as meditation soars upwards, it meets the arched firmament with all its suspended lamps of light. O, let not the simplex et nuda of Gregory be perverted to the Socinian, 'plain and easy for the meanest understandings!' The truth in Christ, like the peace of Christ, passeth all understanding. If ever there was a mischievous misuse of words, the confusion of the terms, 'reason' and 'understanding,' 'ideas' and 'notions,' or 'conceptions,' is most mischievous; a Surinam toad with a swarm of toadlings sprouting out of its back and sides.

Serm. VIII. Mat. v. 16. p. 77.

Ib. C.

Either of the names of this day were text enough for a sermon, Purification or Candlemas. Join we them together, and raise we only this one note from both, that all true purification is in the light, &c.

The illustration of the name of the day contained in the first two or three paragraphs of this sermon would be censured as quaint by our modern critics. Would to heaven we had but even a few preachers capable of such quaintnesses!

Ib. D.

Every good work hath faith for the root; but every faith hath not good works for the fruit thereof.

Faith, that is, fidelity – the fealty of the finite will and understanding to the reason, the light that lighteth every man that cometh into the world, as one with, and representative of, the absolute will, and to the ideas or truths of the pure reason, the supersensuous truths, which in relation to the finite will, and as meant to determine the will, are moral laws, the voice and dictates of the conscience; – this faith is properly a state and disposition of the will, or rather of the whole man, the I, or finite will, self-affirmed. It is therefore the ground, the root, of which the actions, the works, the believings, as acts of the will in the understanding, are the trunk and the branches. But these must be in the light. The disposition to see must have organs, objects, direction, and an outward light. The three latter of these our Lord gives to his disciples in this blessed sermon on the Mount, preparatorily, and, as Donne rightly goes on to observe, presupposing faith as the ground and root. Indeed the whole of this and the next page affords a noble specimen, how a minister of the Church of England should preach the doctrine of good works, purified from the poison of the practical Romish doctrine of works, as the mandioc is evenomated by fire, and rendered safe, nutritious, a bread of life. To Donne's exposition the heroic Solifidian, Martin Luther himself, would have subscribed, hand and heart.

Ib. p. 78. C.

And therefore our latter men of the Reformation are not to be blamed, who for the most, pursuing St. Cyril's interpretation, interpret this universal light that lighteneth every man to be the light of nature.

The error here, and it is a grievous error, consists in the word 'nature.' There is, there can be, no light of nature: there may be a light in or upon nature; but this is the light that shineth down into the darkness, that is, the nature, and the darkness comprehendeth it not. All ideas, or spiritual truths, are supernatural.

Ib. p. 79.

Throughout this page, Donne rather too much plays the rhetorician. If the faith worketh the works, what is true of the former must be equally affirmed of the latter; – causa causæ causa causati. Besides, he falls into something like a confusion of faith with belief, taken as a conviction or assent of the judgment. The faith and the righteousness of a Christian are both alike his, and not his – the faith of Christ in him, the righteousness in and for him. I am crucified with Christ: nevertheless I live; yet, not I, but Christ liveth in me: and the life which I now live in the flesh I live by the faith of the Son of God, who loved me, and gave himself for me.36

Donne was a truly great man; but, after all, he did not possess that full, steady, deep, and yet comprehensive, insight into the nature of faith and works which was vouchsafed to Martin Luther. Donne had not attained to the reconciling of distinctity with unity, – ours, yet God's; God's, yet ours.

Ib. D.

Velle et nolle nostrum est, to assent, or to dis-assent, is our own.

Is not this, even with the saving afterwards, too nakedly expressed?

Ib.

And certainly our works are more ours than our faith is; and man concurs otherwise in the acting and perpetration of a good work, than he doth in the reception and admission of faith.

Why? Because Donne confounds the act of faith with the assent of the fancy and understanding to certain words and conceptions. Indeed, with all my reverence for Dr. Donne, I must warn against the contents of this page, as scarcely tenable in logic, unsound in metaphysics, and unsafe, slippery divinity; and principally in that he confounds faith – essentially an act, the fundamental work of the Spirit – with belief, which is then only good when it is the effect and accompaniment of faith.

Ib. p. 80. D.

Because things good in their institution may he depraved in their practice – ergone nihil ceremoniarum rudioribus dabitur, ad juvandam eorum imperitiam?

Some ceremonies may be for the conservation of order and civility, or to prevent confusion and unseemliness; others are the natural or conventional language of our feelings, as bending the knees, or bowing the head; and to neither of these two sorts do I object. But as to the adjuvandam rudiorum imperitiam, I protest against all such ceremonies, and the pretexts for them, in toto. What? Can any ceremony be more instructive than the words required to explain the ceremony? I make but two exceptions, and those where the truths signified are so vital, so momentous, that the very occasion and necessity of explaining the sign are of the highest spiritual value. Yet, alas! to what gross and calamitous superstitions have not even the visible signs in Baptism and the Eucharist given occasion!

Ib. p. 81. E.

Blessed St. Augustine reports, (if that epistle be St. Augustine's) that when himself was writing to St. Hierome, to know his opinion of the measure and quality of the joy and glory of heaven, suddenly in his chamber there appeared ineffabile lumen, says he, an unspeakable, an unexpressible light, … and out of that light issued this voice, Hieronymi anima sum, &c.

The grave recital of this ridiculous legend is one instance of what I have called the Patristic leaven in Donne, who assuredly had no belief himself in the authenticity of this letter. But yet it served a purpose. As to Master Conradus, just above, who could read at night by the light at his fingers' ends, he must of course have very recently been shaking hands with Lucifer.

Ib. p. 83. D.

Eve's recognition upon the birth of her first son, Cain I have gotten, I possess a man from the Lord.

I have gotten the Jehovah-man, is, I believe, the true rendering and sense of the Hebrew words. Eve, full of the promise, supposed her first-born, the first-born on earth, to be the promised deliverer.

Serm. XII. Mat. v. 2. p. 112.

Ib. B. C. D.

The disposition of our Church divines, under James I, to bring back the stream of the Reformation to the channel and within the banks formed in the first six centuries of the Church, and their alienation from the great patriarchs of Protestantism, Luther, Calvin, Zuinglius, and others, who held the Fathers of the ante-Papal Church, with exception of Augustine, in light esteem, this disposition betrays itself here and in many other parts of Donne. For here Donne plays the Jesuit, disguising the truth, that even as early as the third century the Church had begun to Paganize Christianity, under the pretext, and no doubt in the hope, of Christianizing Paganism. The mountain would not go to Mahomet, and therefore Mahomet went to the mountain.

Ib. p. 115. A.

An excellent passage.

Ib. p. 117. E.

And therefore when the prophet says, Quis sapiens, et intelliget hæc? Who is so wise as to find out this way? he places this cleanness which we inquire after in wisdom. What is wisdom?

The primitive Church appropriated the name to the third hypostasis of the Trinity; hence Sancta Sophia became the distinctive name of the Holy Ghost; and the temple at Constantinople, dedicated by Justinian to the Holy Ghost, is called the Church – alas! now the mosque – of Santa Sophia. Now this suggests, or rather implies, a far better and more precise definition of wisdom than Donne's. The distinctive title of the Father, as the Supreme Will, is the Good; that of the only-begotten Word, as the Supreme Reason, (Ens Realissimum,

6, December, 1831.

Ib. p. 121. A.

The Arians' opinion, that God the Father only was invisible, but the Son and the Holy Ghost might be seen.

Here we have an instance, one of many, of the inconveniences and contradictions that arise out of the assumed contrary essences of body and soul; both substances, and independent of each other, yet so absolutely diverse as that the one is to be defined by the negation of the other.

Serm. XIII. Job xvi. 17, 18, 19. p. 127.

Ib. p. 129. A. B. C.

Ib. pp. 134. 135.

Truly excellent.

Serm. XV. 1 Cor. xv. 26. p. 144.

Ib. D.

Who, then, is this enemy? an enemy that may thus far think himself equal to God, that as no man ever saw God, and lived; so no man ever saw this enemy, and lived; for it is death.

This borders rather too closely on the Irish Franciscan's conclusion to his sermon of thanksgiving: "Above all, brethren, let us thankfully laud and extol God's transcendant mercy in putting death at the end of life, and thereby giving us all time for repentance!"

Dr. Donne was an eminently witty man in a very witty age; but to the honour of his judgment let it be said, that though his great wit is evinced in numberless passages, in a few only is it shown off. This paragraph is one of those rare exceptions.

N. B. Nothing in Scripture, nothing in reason, commands or authorizes us to assume or suppose any bodiless creature. It is the incommunicable attribute of God. But all bodies are not flesh, nor need we suppose that all bodies are corruptible. There are bodies celestial. In the three following paragraphs of this sermon, we trace wild fantastic positions grounded on the arbitrary notion of man as a mixture of heterogeneous components, which Des Cartes shortly afterwards carried into its extremes. On this doctrine the man is a mere phenomenal result, a sort of brandy-sop or toddy-punch. It is a doctrine unsanctioned by, and indeed inconsistent with, the Scriptures. It is not true that body plus soul makes man. Man is not the syntheton or composition of body and soul, as the two component units. No; man is the unit, the prothesis, and body and soul are the two poles, the positive and negative, the thesis and antithesis of the man; even as attraction and repulsion are the two poles in and by which one and the same magnet manifests itself.

Ib. p. 146. B.

For it is not so great a depopulation to translate a city from merchants to husbandmen, from shops to ploughs, as it is from many husbandmen to one shepherd; and yet that hath been often done.

For example, in the Highlands of Scotland in our own day.

Ib. p. 148. A.

The ashes of an oak in the chimney are no epitaph of that oak, to tell me how high or how large that was. It tells me not what flocks it sheltered while it stood, nor what men it hurt when it fell. The dust of great persons' graves is speechless too, it says nothing, it distinguishes nothing. As soon the dust of a wretch whom thou wouldst not, as of a prince whom thou couldst not, look upon, will trouble thine eyes, if the wind blow it thither; and when a whirlwind hath blown the dust of the churchyard unto the church, and the man sweeps out the dust of the church into the church-yard, who will undertake to sift those dusts again, and to pronounce; – this is the patrician, this is the noble, flour, and this the yeomanly, this the plebeian, bran.37

Very beautiful indeed.

Ib. p. 149. C.

But when I lie under the hands of that enemy, that hath reserved himself to the last, to my last bed; then when I shall be able to stir no limb in any other measure than a fever or a palsy shall shake them; when everlasting darkness shall have an inchoation in the present dimness of mine eyes, and the everlasting gnashing in the present chattering of my teeth, and the everlasting worm in the present gnawing of the agonies of my body and anguishes of my mind; when the last enemy shall watch my remediless body, and my disconsolate soul there, – there, where not the physician in his way, perchance not the priest in his, shall be able to give any assistance; and when he hath sported himself with my misery, &c.

This is powerful; but is too much in the style of the monkish preachers: Papam redolet. Contrast with this Job's description of death,38 and St. Paul's sleep in the Lord.

Ib. p. 150. A.

Neither doth Calvin carry those emphatical words which are so often cited for a proof of the last resurrection, – that he knows his Redeemer lives, that he knows he shall stand the last man upon earth, that though his body be destroyed, yet in his flesh and with his eyes shall he see God – to any higher sense than so, that how low soever he be brought, to what desperate state soever he be reduced in the eyes of the world, yet he assures himself of a resurrection, a reparation, a restitution to his former bodily health, and worldly fortune which he had before. And such a resurrection we all know Job had.

I incline to Calvin's opinion, but am not decided. After my skin, must be rendered 'according to, or as far as my skin is concerned.' Though the flies and maggots in my ulcers have destroyed my skin, yet still, and in my flesh, I shall see God as my Redeemer. Now St. Paul says, that flesh and blood cannot

Ib. B. C. (Ezekiel's vision xxxvii.)

I cannot but think that Dr. Donne, by thus antedating the distinct belief of the Jews in the resurrection, "which you all know already," destroys in great measure the force and sublimity of this vision. Besides, it does not seem, in the common people at least, to have been much more than a mongrel Egyptian-catacomb sort of faith, or rather superstition.

In fine. This is one of Donne's least estimable discourses; the worst sermon on the best text. Yet what a Donne-like passage is this that follows!

P. 146. A.

Let the whole world be in thy consideration as one house; and then consider in that, in the peaceful harmony of creatures, in the peaceful succession, and connexion of causes and effects, the peace of nature. Let this kingdom, where God hath blessed thee with a being, be the gallery, the best room of that house, and consider in the two walls of that gallery, the Church and the state, the peace of a royal and religious wisdom. Let thine own family be a cabinet in this gallery, and find in all the boxes thereof, in the several duties of wife and children, and servants, the peace of virtue, and of the father and mother of all virtues, active discretion, passive obedience; and then lastly, let thine own bosom be the secret box and reserve in this cabinet, and then the gallery of the best home that can be had, peace with the creature, peace in the Church, peace in the state, peace in thy house, peace in thy heart, is a fair model, and a lovely design even of the heavenly Jerusalem, which is visio pacis, where there is no object but peace.

Serm. XVI. John xi. 35. p. 153.

Ib. C.

The Masorites (the Masorites are the critics upon the Hebrew Bible, the Old Testament) cannot tell us, who divided the chapters of the Old Testament into verses: neither can any other tell, who did it in the New Testament.40

How should the Masorites, when the Hebrew Scriptures were not as far as we know divided into verses at all in their time? The Jews seem to have adopted the invention from the Christians, who were led to it in the construction of Concordances.

Ib. p. 154. E.

If they killed Lazarus, had not Christ done enough to let them see that he could raise him again?

Malice, above all party-malice, is indeed a blind passion, but one can scarcely conceive the chief priests such dolts as to think that Christ could raise Lazarus again. Their malice blinded them as to the nature of the incident, made them suppose a conspiracy between Jesus and the family of Lazarus, a mock burial, in short; and this may be one, though it is not, I think, the principal, reason for this greatest miracle being omitted in the other Gospels.

Ib. p. 155. B.

Christ might ungirt himself, and give more scope and liberty to his passions than any other man; both because he had no original sin within to drive him, &c.

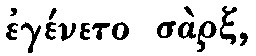

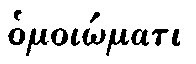

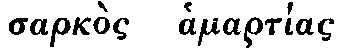

How then is he said to have _condemned sin in the flesh?_ Without guilt, without actual sin, assuredly he was; but

Ib. D.

I can see no possible edification that can arise from these ultra-Scriptural speculations respecting our Lord.

Ib. p. 157. A.

Though the Godhead never departed from the carcase … yet because the human soul was departed from it, he was no man.

Donne was a poor metaphysician; that is, he never closely questioned himself as to the absolute meaning of his words. What did he mean by the 'soul?' what by the ' body?'42

Ib. D.

And I know that there are authors of a middle nature, above the philosophers, and below the Scriptures, the Apocryphal books.

A whimsical instance of the disposition in the mind for every pair of opposites to find an intermediate, – a mesothesis for every thesis and antithesis. Thus Scripture may be opposed to philosophy; and then the Apocryphal books will be philosophy relatively to Scripture, and Scripture relatively to philosophy.

Ib. p. 159. B.

And therefore the same author (Epiphanius) says, that because they thought it an uncomely thing for Christ to weep for any temporal thing, some men have expunged and removed that verse out of St. Luke's Gospel, that Jesus, when he saw that city, wept.43

This, by the by, rather indiscreetly lets out the liberties, which the early Christians took with their sacred writings. Origen, who, in answer to Celsus's reproach on this ground, confines the practice to the heretics, furnishes proofs of the contrary himself in his own comments.

Ib. p. 161. D.

That world, which finds itself in an authumn in itself, finds itself in a spring in our imaginations.