Полная версия:

Ancestral home of the Indo-Europeans

In the Iranian highlands, in the mountains of Zagros (on the western slopes and in the wetter northern part, between 1000 m and 1800 m), park oak forests with elm and maple are common, and wild mulberries, poplar, wall oak, and figs are found in the valleys. Due to the fact that in the middle period 1 thousand BC hitherto defined by climatologists as the period of cooling and moistening with respect to the climatic optimum of the Holocene (4—3 thousand BC) and the previous time (7—5 thousand BC), there is no reason to assume in these southern territories there is a much more humid and colder climate of 7—3 thousand BC, the time in question in the work of T. V. Gamkrelidze and V. V. Ivanov.

It should be noted that the significant fact is that in the common Indo-European vocabulary there are no names for many trees that are widespread in the Near East and Asia Minor from ancient times. These are:

olive (the primary focus of shaping in Asia Minor);

apricot (which was grown in 4 thousand BC even by residents of Tripoli settlements);

edible chestnuts, known in these territories from the Tertiary period;

quinces, which grows wild in northern Iran, Asia Minor and the Caucasus, where the primary centers of morphogenesis and introduction to culture were located;

loquat, in the wild distributed in the Caucasus, the Crimea and the North. Iran (the primary focus of shaping and introducing into the culture of Asia Minor);

almonds (the primary focus of forming Asia and the surrounding areas);

figs or figs, fig trees, found wild in the Near East, Asia Minor and the Mediterranean; and, finally, a date, the primary focus of domestication of which is Southern Iran and Afghanistan, where this plant was introduced into the culture in 5—3 thousand BC.

Olive

Blooming apricot

Apricot

Almond

Figs

Date fruit

Mushmula

Quince

This list can be greatly expanded. But even in such a fragmented form, he confirms that neither Front, nor Asia Minor, nor the Armenian Highlands could be the oldest ancestral home of the Indo-Europeans. And here again I would like to refer to the conclusion of P. Friedrich that: «the Pre-Slavic best of all other groups of Indo-European languages retained the Indo-European system of tree designation», and «the speakers of the common Slavic language lived in the ecological Slavic period (in particular, defined by wood flora), similar or identical to the corresponding zone of the common Indo-European, and after the general Slavic period, the carriers of various Slavic dialects continued to a significant extent to live in a similar area.»

Chapter 3 Plants of the Indo-European ancestral home

Birch (Betula) (map No. 1), a genus of deciduous monoecious trees and shrubs of the birch family. The bark of the trunks is white or of a different color, up to black. It usually grows rapidly, especially at an early age. It easily populates the free vegetation of space, often being a pioneer breed.

About 100 polymorphic species grow in the temperate and cold regions of the Northern Hemisphere and in the mountains of the subtropics; in the USSR – about 50 species. Many birches matter as valuable forest-forming species; especially warty birch (B. pendula, or B.verrucosa), fluffy birch (B. pubescens), flat birch (B.

platyphylla), ribbed or yellow birch (B. costata), Schmidt or iron birch (B. schmidtii). Most species are photophilous, drought-resistant, frost-resistant, and undemanding to soils. Wood, as well as many types of birch bark, is used in various sectors of the economy. The buds and leaves of warty birch and fluffy birch are used for medicinal purposes.

The most common species is warty birch. Trees reach 25 m. Tall. Birch tolerates some salinization of the soil and dry air, lives 150 years. It occurs in Western Europe up to 65° N., in the USSR throughout the forest and forest-steppe zone of the European part, in Western Siberia, Transbaikalia, Sayan Mountains, Altai and the Caucasus. It grows in a mixture with conifers and deciduous species or in places forms extensive birch forests, and in the forest-steppe zone of the Volga region and Western Siberia – birch spikes interspersed with fields and steppe spaces. Wood is appreciated in furniture production.

Flat birch

Yellow birch

Warty birch

Fluffy birch

Birch Schmidt

T. V. Gamkrelidze and V. V. Ivanov believe that this tree grew on the Indo-European ancestral home. «Birch species are currently found throughout the temperate (northern) zone of Eurasia, as well as in the mountainous regions of the more southern zones, where it grows to a height of about 1,500 m. (In particular in the Caucasus, on the spurs of the Himalayas and in the mountainous regions of Southern Europe) In the subboreal period (about 3300—4000 BC), birch was also distributed in the more southerly belt… The presence of a common word for birch in the Indo-European suggests familiarity with the ancient Indo-European tribes, which was possible either in the zone temperate climate (in Europe at latitudes from the north of Spain to the north of the Balkans and further east to the lower reaches of the Volga), or in mountainous regions of the more southern area of the Near East.»

However, academician L.S. Berg in 1947 emphasized that in the northern part of Eastern Europe 13—12 thousand years ago there were forests of birch and pine.

In the warming that began 11—10 thousand years ago, the absolute maximum of birch was noted.

These conclusions are also confirmed by materials prepared by domestic paleoclimatologists for the 12th INCW Congress (Canada. 1987), indicating that in the Vychegda and Verkhnyaya Pechora river basins in layers 45210 +1430 years ago pine and birch prevailed in combination with cereal forbs. In the forests, pine made up 44%, birch up to 24%, spruce up to 15%. In the north of the Pechersk lowland in the postglacial period, i.e. 10—9 thousand years ago, «woody vegetation developed territories» and these were forests of birch, spruce and pine. Data on the Belarusian Polesie indicate that 12,860 +110 years ago (at the beginning of 11th BC) pine-spruce forests and associations of pine-birch forests with an admixture of broad-leaved: oak, elm and linden were widespread here.

Samples of peat from the marshes of the Yaroslavl, Leningrad, Novgorod and Tver regions, performed in the laboratory of the Institute. V. I. Vernadsky, confirm that the peak of birch distribution dates back to about 9800 years ago, 7700 years ago – the absolute dominance of birch.

L. S. Berg wrote: «A study of the history of vegetation in the postglacial period, carried out by analyzing pollen from peat, showed that in the central part of the Union, immediately after the retreat of the glacier, birch and willow appeared in large numbers, and then, in the so-called subarctic time, prevalence passed to spruce and birch; in the next boreal era, birch and pine began to dominate.»

I must say that birch is one of the most important forest-forming species in Eastern Europe since the time of the Mikulinsky interglacial (130—70 thousand years ago) and up to the present day. The authors of the «Paleography of Europe over the past hundred thousand years» note that: «Tracing the Holocene history of birch, we can think that in the modern forests of the European part of the USSR primary birch forests are much more widespread than is usually assumed.» At the same time, nothing testifies to the wide distribution of birch in antiquity in the Near East and on the Armenian Highlands. L. S. Berg emphasized that: «The climatic situation of Palestine at the northern border of palm culture and at the southern limit of grape cultivation has not changed since biblical times.»

The authors of the Indo-European language and Indo-Europeans write: «The main economic value of birch is determined by the fact that it served in antiquity and still serves in separate traditions as material for the manufacture of a wide variety of objects from shoes, dishes, baskets, to writing material in individual cultures, in particular among the Eastern Slavs and in India until the sixteenth century.» A. A. Kachalov points out that: «the inhabitants of the Himalayas use birch bark useful for this purpose in our time.»

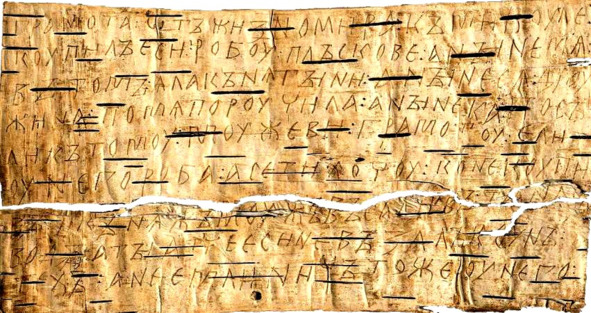

The bark of trees has been used for many millennia among different peoples as writing material on which signs were originally left in the Mesolithic and Neolithic. The use of birch bark as writing material was common in antiquity. The emperors Domitian and Commodus had notebooks from this material, Pliny the Elder and Ulpian report that the bark of other trees was also used for writing. In Latin, the concepts of «book» and «woody bast» are expressed in one word «liber».

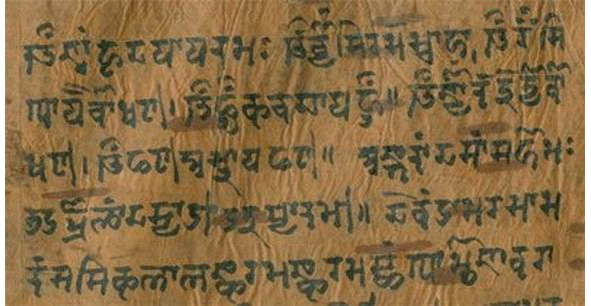

Hundreds of Roman letters on birch bark were found during excavations of the Roman fort of Vindoland in northern England. There is evidence of birch bark letters in Sweden and Norway of the 15th century; Swedes used them later. A birch bark letter of 1570 with a German text was kept in Tallinn. The famous Golden Horde manuscript on birch bark and Tibetan medieval birch bark letters from Tuva. In India, Sanskrit manuscripts on birch bark, a number of Buddhist texts on birch bark are known.

Diploma on birch bark

Sanskrit letter on birch bark

«The connection of trees – birch, beech, hornbeam with the terminology of writing indicates the technique of writing and making materials for writing in ancient Indo-European cultures. The emergence of writing and writing is the basis in these cultures for the use of wood and wood material, on which signs or nicks were applied using special wooden sticks. This writing technique, characteristic of a number of early Indo-European cultures, reflects, obviously, a typologically more archaic degree of writing development than carving signs on stone, or putting them on clay tablets, or on specially treated animal skin.»

I must say that it is difficult to imagine that a simpler, more affordable, maneuverable and less laborious letter on birch bark was more archaic (or primitive) than an inconvenient, bulky letter on clay tablets or inscriptions on stone. Indeed, if there were both clay and birch bark from the early Indo-Europeans, they would hardly have switched from writing on birch bark to using clay tablets for business correspondence or for business records.

In addition, the question arises why birch bark, as a material for writing, was preserved precisely in the East Slavic and Indian ethnic range. If you follow the findings of T. V. Gamkrelidze and V. V. Ivanov, the Slavic and Indo-Iranian branches of the Indo-European community dispersed even on the territory of their supposed common ancestral home in Asia Minor (where there are practically no birches). The Pre-Slavs went to Eastern Europe, and the Indo-Iranians moved to Iran (where birch is not common) and Hindustan, where only in the Himalayas at an altitude of 2500—4300 m. grows «useful birch», «Jacquemont birch» and, finally, the birch of the section of acuminatum lives – a tree 20—30 m. high with very large leaves. But these trees are not widespread in India and are considered endonomics of a very narrow range.

Birch in the Himalayas

But in the Indian tradition, birch bark is not just writing material, but sacred material: on birch bark (and only on birch bark) a record was made of marriage in the higher castes, and without this record on birch bark, marriage was not considered valid. This situation could not develop in areas where birch is almost not widespread. Birch bark could become material only where birch has been one of the main forest-forming species for many millennia – in the forest strip of Eastern Europe. It makes sense to pay attention to the following circumstance. T. V. Gamkrelidze and V. V. Ivanov emphasizes that birch bark was used for writing in the most ancient Indo-European cultures and was preserved in such quality among the Eastern Slavs and in India until the 16th century.

But the ancestors of the East Slavic peoples and Aryan peoples of North-West India diverged in the middle of 2 thousand BC Nevertheless, birch bark, as a material for writing, was preserved precisely among the Eastern Slavs and Indians.

It follows from this that birch bark was still on their common ancestral home as a material for writing. But then the conclusion is also natural that long before the middle of 2 thousand BC the ancestors of the eastern Slavs had writing and the predecessors of the Novgorod and Pskov birch bark letters were older than them for many millennia. It is also interesting that in the North Russian tradition birch bark and in the 19th century (as in India) was precisely sacred material for writing.

This is evidenced by the story of an outstanding ethnographer of the 19th century.

S. V. Maksimov about the birch bark book, which the Archangel old man-Pomor, ready to give any other manuscript, decorated with miniatures, Old Believers book, did not want to sell him for any money.

S. V. Maksimov notes that this book, «written by half-mouth» on birch bark, «finely and successfully stripped and assembled, stitched in quarters… The written was disassembled as conveniently as the written on paper, the letters did not spread out, but stood straight, one beside the other: another paper makes letters worse…

the book was somehow twisted into simple, birch bark, planks… (to write such a book) sticky soot is made from burnt birch peel, which, when diluted on the water, gives decent ink at least those that can leave a very noticeable mark on their own, if they are wiped over the top layer. The eagles and wild geese, which are many on the tundra and which are difficult to fly away from the well-aimed shot of the usual hunters, give good feathers always conveniently peeling over the layers of birch bark, which can be turned into pages and on which you can write soon and, perhaps, clearly, «writes S. V. Maksimov.

The sacred nature of birch bark, as a material for writing, is evidenced by the customs preserved in the Russian North almost to the present day. So A. A. Veselovsky in his «Essays on the History of the Life and Work of Peasants of the Vologda Province» describes the rite of «unsubscribing,» in which the healer, when whispering, writes a note and puts it into the wind and it becomes easier for the patient. «They write a petition on birch bark and it is carried away by «wind-father».

From the same series, it is customary to write conspiracies and letters to the devil – «bondage» – on birch bark, and the text is not written (in the literal sense of the word), but is applied by soot in the form of erratic strokes, oblique crosses, winding lines, etc. All this testifies to the now anciently forgotten, supplanted Cyrillic alphabet, the ancient Slavic writing system. Perhaps her relics are mysterious signs on the manure of northern Russian icons and the so-called «ornaments» painted by Dionysius on the arch of the portal of the Cathedral of the Nativity of the Virgin in the village of Ferapontovo.

Oak (Quercus) (map No. 2), a genus of deciduous or evergreen trees, rarely shrubs of the beech family. The leaves are alternate, simple, cirrus, lobed, serrated. The fruit is a single-seeded acorn, partially enclosed in a cup-shaped woody bun

Oak grows slowly. Photophilous. Some species are drought-tolerant, quite winter-hardy, and less demanding on soils. About 450 species in the temperate, subtropical and tropical zones of the Northern Hemisphere. In the USSR – 20 wild species in the European part, in the Far East and the Caucasus; in culture 43 species.

English or summer oak (Q.robur) – a tree up to 50 m high. It survives up to 1000 years. Distributed in the European part of the USSR, in the Caucasus and almost throughout Western Europe. In the northern part of the range, it grows along river valleys, to the south reaches the watersheds and forms mixed forests with spruce, and in the south of the range – pure oak forests; in the steppe zone it is found along ravines and gullies. One of the main forest-forming species of broad-leaved forests of the USSR. Rock or winter oak (Q.petraea), found in the west of the European part of the USSR, in the Crimea and in the North Caucasus. Georgian oak (Q. iberica) grows in the eastern part of the North Caucasus and Transcaucasia; in the alpine zone of these regions, large anther oak (Q.macranthera) grows. The main species of the valley forests of the East Caucasus is the long-legged oak (Q. longipe). An important forest-forming species in the Far East is Mongolian oak (Q.mongolica), a frost-resistant and drought-resistant tree.

Wood has high strength, hardness, durability and beautiful texture. Used in shipbuilding, underwater structures, as does not give in to decay; it is used in furniture, carpentry, cooperage, building houses, etc. Some types of bark (Cork oak – Q.suber) give cork. Bark and wood contain tannins used to tan leather. The dried bark of young branches and thin trunks of oak oak is used as an astringent in the form of a water decoction for rinsing in inflammatory processes of the oral cavity, pharynx, pharynx, as well as lotions in the treatment of burns. Acorns go to feed for pigs.

Cork Oak

Rock Oak

T. V. Gamkrelidze and V. B. Ivanov believe that the early Indo-Europeans could get to know this tree only in the southern regions of the Mediterranean (including the Balkans and the northern part of the Middle East), because «oak forests are uncharacteristic of the northern regions of Europe, where they spread only from the 4th-3rd millennium BC.»

However, it is now known that oak forests were widespread in northern Europe (and Eastern Europe in particular) during the Mikulinsky interglacial period (130—70 thousand years ago). During the peak of the Valdai glaciation (20—18 thousand years ago), in a number of areas of the Russian Plain there were forests with the participation of broad-leaved species such as oak and elm. At the beginning of 11 thousand BC (12860 +110 years ago) in the Belarusian Polesie there were widespread associations of pine-birch forests with an admixture of broad-leaved: oak, elm and linden. During the Mesolithic, a significant part of the territory of modern Vologda and Arkhangelsk regions was covered with deciduous forests, which include oak forests. S. V. Oshibkina notes that at the Mesolithic site of Pogostishche-I in the East Prionegie (7 thousand BC), the forest consisted of birch, pine, a small amount of spruce and mixed oak forest. L. S. Berg noted that as early as 9—8 thousand BC «in the Neva basin separate pollen grains of broad-leaved species and hazel» appear, and in 5—4 thousand BC here noted «the great distribution of oak forests with linden, elm and hazel.»

The conclusions of L. S. Berg are confirmed by data obtained by domestic geochemists in 1965. So it is noted that, starting from the turn of 7—6 thousand BC «pollen spectra are characterized by a high content of broad-leaved pollen… The climax points of the curves of oak, elm, hazel and alder are located here.» We emphasize that the culmination of the distribution of oak in the Tver region dates back to 6945 years ago (the beginning of 5 thousand BC), and in the Leningrad region – to 7790 years ago (the beginning of 6 thousand BC). In addition, in the Neolithic and Bronze Age, it was in Eastern Europe that the largest oak forest zone in Europe was located.

Thus, the thesis about the presence of oak forests in ancient Indo-European time only in the Mediterranean, mountainous areas of Mesopotamia and adjacent areas is completely groundless.

Beech (Fagus) (map No. 3), a genus of monoecious plants of the beech family. Trees up to 50 m high with smooth gray bark. 10 species in extratropical regions of the Northern Hemisphere; in the USSR – 3 species. Acorn fruits (nuts) are provided with a woody shell. Beeches are shade-tolerant, but heat-loving. In the mountains they rise up to 2300 m. They form clean or mixed forests. They live up to 400 years.

The wood is dense, heavy, well polished; in air it is quickly destroyed, but in water and in the wet states it is very durable; used for the manufacture of musical instruments, furniture. The fruit contains poison, which decomposes upon frying; oil is made from fruits.

Beech

The authors of the «Indo-European language and Indo-Europeans» note that the name «beech» is not in the Indo-Iranian languages. This is more than strange if we accept the hypothesis of V. V. Ivanov and T. V. Gamkrelidze about the Near-Asian ancestral home of Indo-Europeans. After all, this tree was in ancient times one of the main forest-forming in the Transcaucasia and Western Asia. The fact that the ancient Indo-European name of beech has not been preserved in the Indian language can still be explained – there is no beech on the territory of Hindustan.

Eastern beech

But how could the Iranians lose this ancient Indo-European name if the beech is the main forest-forming not only in the Near East and the Armenian Highlands (the supposed oldest ancestral home), but also in the Iranian Highlands – the new homeland of the Iranians (according to T.V. Gamkrelidze and V. V. Ivanov)?

After all, G. I. Tanfiliev, the chief botanist of the Imperial Botanical Garden, an outstanding phytogeographer and connoisseur of the flora of Russia, describing the vegetation of the Caucasus in 1902, noted that the forests here consist mostly of beech mixed with chestnut and oak. At present: «in the Caucasus, beech occupies almost half of the total area covered by forests. It is widespread on the northern slopes of the Caucasus, in Transcaucasia it is characterized by almost continuous distribution, and only in the upper reaches of individual rivers gives way to conifers. It runs along the main ridge from the Black Sea coast to the eastern border of the forests (Shemakha), through the Lesser Caucasus, goes east to the Terter River, and in the east it is again found in Talysh, leaving the foothills of Elbrus to Iran.»

The same picture was observed in antiquity: pollen analysis of samples from the bottom of the Black Sea, dating from the beginning to the middle of 6 thousand BC, when there was a rapid filling of the freshwater Black Sea with salt water from the Bosphorus, indicate the presence of forests in this area from hornbeam, beech, oak and elm.