Полная версия:

The Ship of Dreams

By the time the Titanic had been completed, the question of Irish independence, whether in part or in full, was the blood seeping beneath a closed door in Belfast. Fear of it preoccupied everybody, including Thomas Andrews. In his own political views, Andrews was described by family friends as ‘an Imperialist, loving peace and consequently in favour of an unchallengeable Navy. He was a firm Unionist, being convinced that Home Rule would spell financial ruin to Ireland.’ However, he was uneasy with the perceptible drift towards Irish politics being governed by ‘passion rather than by means of reasoned argument’.[49] Many Ulster Protestants sincerely believed, and were proved correct in their suspicions, that Irish independence would constitute a major triumph for Catholicism in the island, with an Irish government choosing to grant special status to the Catholic faith.[50] Ironically, the north’s fevered insistence on absenting itself from independence was the behaviour of Laius after the Oracle since Ulster’s secession would mean the removal of the majority of Irish Protestants from a future Irish state, whatever the strength of that state’s ties to Britain, thus enabling many of the events they claimed to fear. As a southern lawyer practising in Belfast tried in vain to warn his unionist friends, if the predominantly Protestant north separated from the predominantly Catholic south, ‘you would have not one, but two, oppressed minorities’.[51]

Protestant fears of being outnumbered and thus overruled by their Catholic compatriots were lent unfortunate credence by Pope Pius X’s issuing of the Ne Temere decree of 1907. The decree ruled that any marriage between a Catholic and a Protestant was invalid unless it was witnessed by a priest, implicit within that stipulation and often explicit in its application being a priest’s refusal to officiate unless an undertaking was given that any children born to that couple were raised Catholic. Ne Temere seemed particularly unhelpful in the Irish context because it negated a papal rescript, issued by Pius VI in 1785, which had allowed for the legality of mixed marriages in Ireland, even if they were not solemnised before a Catholic priest.[52] Viewed as pastoral care by its defenders and lambasted by critics as prejudice by stealth, Ne Temere resulted four years later in the McCann case, when the marriage between a Belfast resident called Alexander McCann, a Catholic, and his Protestant wife Agnes fell apart. A private sorrow became a public circus when McCann’s local priest allegedly encouraged the separation and certainly helped Mr McCann gain sole custody of his children, despite the fact that the McCanns had married before the publication of Ne Temere. Agnes McCann went to her local minister, Reverend William Corkey, who had already regularly waxed apoplectic in his sermons about the ‘foul’ Ne Temere decree and saw in the McCann case the inevitable fruition of Pius X’s edict.[53] As such things often did in Edwardian Belfast, the issue moved from the pulpit to the press to protests, the latter of which spread from Belfast to London, Dublin and Glasgow.[54] At one rally, the McCanns’ marriage certificate was held up before the crowd, as a Presbyterian clergyman roared, ‘I hold in my hand a marriage certificate bearing the seal of the British Empire, and recording the marriage of Alexander McCann and Agnes Jane Barclay. This certificate declares that according to the law of Britain these two are husband and wife. This Papal decree says their marriage is “no marriage at all”. Which law is going to be supreme in Great Britain?’[55] The pursuit of the answer had already fractured lifelong friendships and it looked, in 1912, as if it had the potential to destabilise an empire.

*

As he boarded the Titanic, Andrews received a note from one of his colleagues saying that there was a problem in one of the boiler rooms. Since this was their first full run, that was to be expected. A fire had started raging when some of the coal stored in one of the bunkers had caught fire and there was no chance of putting it out before the ship was due to start her tests. Should they postpone them? No, not if the fire in question could be contained. An extra squadron of stokers and firemen was deployed to monitor the troubled boiler room, the others were fired up and, without fanfare, the Titanic took to the ocean for the first time, beginning six hours of technical manoeuvres and trials.

The sea trial had originally been scheduled for the previous day, but was postponed in the face of high winds which would have made it impossible to vet properly the Titanic’s speed, turning and stopping capabilities in calm seas. The winds had since died down, allowing for the leviathan to undertake manoeuvres which saw her tested at a variety of speeds, ranging from 11 to 21½ knots, the latter being close to her expected full speed. She was also halted at 18 knots, coming to a stop three minutes and fifteen seconds later, at just three and a half times her own length which, for a ship of her size travelling at that velocity, was judged yet another encouraging indicator of her safety.[56] On board, Andrews meticulously watched each manoeuvre, joined by some of the colleagues who knew the ship almost as well as he did, chief among them Francis Carruthers, the British Board of Trade’s on-site surveyor, and Edward Wilding, the yard’s Senior Naval Architect. As the Board’s eyes at Harland and Wolff, Carruthers had made hundreds of trips to the Titanic over the course of her construction. Wilding, like Carruthers an Englishman who had relocated to Ireland for his job, was not just a colleague but a friend, who had been a guest at Andrews’ wedding in 1910. Together, the three men had watched Titanic’s ‘vast shape slowly assuming beauty and symmetry’. She was, thus far, the crowning glory of Andrews’ and Wilding’s careers, ‘an evolution rather than a creation’, according to one of their contemporaries, ‘triumphant product of numberless experiments, a perfection embodying who knows what endeavour, from this a little, from that a little more, of human brain and hand and imagination’.[57]

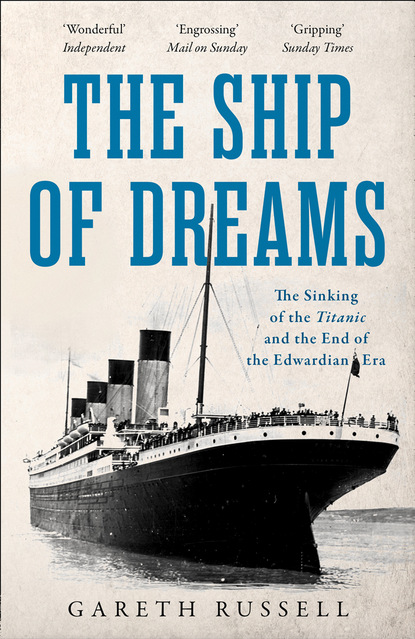

The Titanic in Belfast Lough during her sea trials.

The completed steamship Titanic at Belfast, Ireland (Science History Images/Alamy Stock Photos)

On her way back into Belfast, Titanic passed the seaside town of middle-class Holywood on one side of the Belfast Lough and working-class Carrickfergus on the other. In both towns, it was time for local chapters of the Orange Order to be out on the streets practising their music, hymns and configurations in preparation for the start of marching season, an annual series of parades held to commemorate the anniversary of King William III’s victory over his Catholic uncle at the Battle of the Boyne in 1690 and the ensuing establishment of a legal Protestant ascendancy in Ireland for the next century. The Orange Order, founded as that ascendancy had cracked open in defeat at the end of the eighteenth century, organised itself somewhere between masonic and military lines, claiming nearly one-third of northern Protestant men as members.[58] Each was required, by oath, to ‘love, uphold, and defend the Protestant religion, and sincerely desire and endeavour to propagate its doctrines and precepts [and] strenuously oppose and protest against the errors and doctrines of the Church of Rome; he should, by all lawful means, resist the ascendancy of that church’. A later extension to the formula, added in 1860, prohibited members from ever attending a Roman Catholic religious service.[fn2][59]

Disruption, intimidation and violence at Order events had resulted in legislation curtailing its parades in the middle of the nineteenth century, and its reputation for disruptiveness had lasted, even among many Protestants, until the 1870s.[60] By 1912, however, its influence in the north of Ireland was enormous. Even politicians and clergymen who were indifferent or hostile to the Order’s aims, like the MP Sir Edward Carson who privately compared it to an ancient Egyptian mummy, a preserved and desiccated corpse of something that had mattered long ago, ‘all old bones and rotten rags’, felt that they had to join if they stood any chance of appealing to working-class voters.[61] Andrews and his brothers came from a family with a long association with the Order who marched with its orange sashes around their necks, every year.[62] Andrews would be back in Belfast by the time of the Order’s parades at the high point of marching season, 12 July.[fn3] Each lodge had their own banner, depicting a vividly rendered moment in Irish Protestant history – a particular favourite was an image of drowning settlers, usually women and children, piously clutching a cross as they were butchered, with the slogan ‘My Faith Looks Up to Thee’, victims of anti-Protestant massacres carried out in 1641. On the reverse of all banners, long-dead King William forded the waters of the Boyne river atop his white steed, his sword already drawn for the children of the Glorious Revolution and their descendants, who would defend its legacy. As the Order’s most famous song proclaimed:

For those brave men who crossed the Boyne have not fought or died in vain,

Our Unity, Religion, Laws, and Freedom to maintain,

If the call should come we’ll follow the drum, and cross that river once more

That tomorrow’s Ulsterman may wear the sash my father wore!

By April 1912, the Order had helped rebrand Home Rule as ‘Rome Rule’. On the day the Titanic conducted her trials, a letter to the Belfast News-Letter from a local headmaster opined, ‘Under Rome Rule, there is no possible future for unionists, but despairing servitude or its preferable alternative – annihilation.’[63] Hysteria had trumped civic virtues. Rome was on the march. Upper-class Protestants had forgotten their fears of the radicalised workers and had instead given themselves over to the giddy novelty of Protestants straining together in common cause, as they had in days of old – or so the banners of the Orange Order told them. A paramilitary organisation, the Ulster Volunteer Force, was formed with thousands of recruits training on aristocratic estates as guns were smuggled into the island to arm them. One of Andrews’ compatriots wrote with moist-eyed pride that it was ‘indeed a wonderful time. Every county had its organisation; every down and district had its own corps. The young manhood of Ulster had enlisted and gone into training. Men of all ranks and occupations met together, in the evenings, for drill. This resulted in a great comradeship. Barriers of class were broken down or forgotten entirely. Protestant Ulster had become a fellowship.’[64]

The sound of these flute-serenaded battle cries followed the Titanic in and out of her home waters. She was born in this heartland of an industrial miracle, with its rich and explosive confusion. We might look back now and think it unutterably bizarre that Ulster was prepared to immolate itself to prevent a quasi-independence that might never have matured to full secession if the north had chosen to be a part of it, but to the participants in this quarrel they were contenders in a Manichean struggle for the very soul of Ireland. In London, the new King was frantically trying to organise a preventative peace conference at Buckingham Palace, hopeful of exploiting unionism’s atavistic attachment to the Crown to force its adherents back into line, and three days before the Titanic left Belfast the constitutional nationalist Sir John Redmond, leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party, gave a speech in Dublin, squarely aimed at his compatriots in the north – ‘We have not one word of reproach or one word of bitter feeling,’ he promised. ‘We have one feeling in our hearts, and this is an earnest longing for the arrival of the day of reconciliation.’[65]

No one was listening. It was a man of action who flourished in April 1912, drowning out men of prudence. Unionism was now dominated by leaders like the lawyer Edward Carson, who had once served as the prosecuting counsel against Oscar Wilde, and the Andrewses’ family friend, the ferociously uncompromising Sir James Craig. To make explicit how far they were prepared to go if Home Rule was extended to Ulster, the Ulster Volunteer Force, the Orange Order and the heads of the north’s major industries were organising one of the largest mobilisations of political sentiment in Irish history, a covenant due to be paraded through the province to an enormous final rally outside Belfast City Hall.[66] Agents were sent out to help those in the smaller towns and countryside who wanted to sign. Tommy Andrews and the men in his family intended to sign this declaration:

being convinced in our consciences that Home Rule would be disastrous to the material well-being of Ulster as well as of the whole of Ireland, subversive to our civil and religious freedom, destructive of our citizenship, and perilous to the unity of the Empire, we, whose names are underwritten, men of Ulster, loyal subjects of His Gracious Majesty King George V., humbly relying on God whom our fathers in days of stress and trial confidently trusted, do hereby pledge ourselves in solemn Covenant, throughout this our time of threatened calamity, to stand by one another in defending, for ourselves and our children, our cherished position of equal citizenship in the United Kingdom, and in using all means which may be found necessary to defeat the present conspiracy to set up a Home Rule Parliament in Ireland. And in the event of such a Parliament being forced upon us, we further solemnly and mutually pledge ourselves to refuse to recognise its authority. In sure confidence that God will defend the right …[67]

Partly from despair and frustration that unionism would never willingly give so much as an inch in compromise and partly in tune with the mounting radicalisation of nationalist politics across Europe, Irish nationalism was evolving and splitting into republicanism, itself increasingly shaped by die-hards like Pádraig Pearse. Moderation had become a tarnished virtue, a tired or even pathetic concept. Although he begged his followers to ‘restrain the hotheads’, Edward Carson simultaneously urged them to ‘prepare for the worst and hope for the best. For God and Ulster! God Save the King!’[68] On the other side of the soon actualised barricades, Pearse urged his followers to hope for civil war, to pray for rebellion and for all of British Ireland to vanish in flames regardless of the human cost, because ‘Blood is a cleansing and sanctifying thing, and the nation that regards it as the final horror has lost its manhood.’[69] From their respective demagogues, all sides in Ireland heard the sibyl cry of their pasts, promising them the future glory of a war without ambiguity. Protestant and Catholic, loyalist and nationalist, Ireland would willingly wrestle itself off a cliff edge, plunging the entire island into the unknown. The head of the police service, the Royal Irish Constabulary, told the Chief Secretary of Ireland, ‘I am convinced that there will be serious loss of life and wholesale destruction of property in Belfast on the passing of the Home Rule bill.’[70]

When he arrived back in Belfast that night, after the sea trials, Andrews sent a note to his wife in Malone. Everything had gone well; there were one or two problems, which would no doubt be fixed by the time the ship reached Southampton three days later. Francis Carruthers had been duly satisfied by Titanic’s performance and he had granted her the Board of Trade’s standard twelve-month certificate as a passenger ship.[71] Andrews and Wilding spent the night on board, to prepare for the early-morning departure to England. The Union Jack fluttered from one of the Titanic’s flagpoles as the sun set around the slumbering leviathan with the fire burning unchecked within her interiors.

3

Southampton

[The Titanic] was so much larger than one even expected; she looked so solidly constructed, as one knew she must be, and her interior arrangements and appointments were so palatial that one forgot now and then that she was a ship at all. She seemed to be a spacious regal home of princes.

Ernest Townley, interview given to the Daily Express (16 April 1912)

ONE WEEK AFTER HER MIDNIGHT ARRIVAL AT Southampton, the Titanic’s main mast ran the company’s red flag with its eponymous white star, fluttering over final preparations for her first commercial voyage.[1] The day of departure, Wednesday 10 April, was overcast in the south of England, with the sun occasionally appearing from behind the scudding clouds to provide a mild temperature of about 9 degrees centigrade as the crew, numbering about 900, were divided into three groups for the muster. Firemen, seamen and those assigned to care for the soon-to-board passengers went through their final medical checks and a head count, carried out under the watchful eye of another representative of the Board of Trade, who then proceeded to observe as two of the ship’s twenty lifeboats were lowered down the side with eight trained crew wearing their lifejackets. Typically, this inspection would involve the tested lifeboats unfurling their sails, but an uncooperative breeze put pay to that, so the white-painted wooden craft were successfully raised back on to deck and into their davits, with their virgin sails left unfurled. Vast quantities of luggage were being manoeuvred on board. Pieces bound for the first-class quarters bore White Star-provided labels with variants of ‘CABIN’ or ‘STATEROOM’, to indicate that they should be taken to the passenger’s bedroom; ‘BAGGAGE ROOM’ or ‘WANTED’, if they were not to go immediately to their accommodation but contained items which might be required later in the voyage, a helpful utilisation of space given the upper classes’ minimum requirement of three outfit changes daily; and ‘NOT WANTED’, if the pieces were to go into the hold until disembarking.[2]

Thomas Andrews had arrived on board half an hour or so after dawn that morning, checking out from his interim accommodation at the nearby South-Western Hotel, where he had stayed in the week since leaving Belfast.[3] The days in between had been spent overseeing the last touches to the Titanic’s accommodation, which produced the kind of productive mania at which Andrews excelled. The ship’s schedule had already been altered, and then squeezed, by her elder sister’s accident in the Southampton waters a few months earlier when, moments after departure, the Olympic had collided with the British warship Hawke.[4] Mercifully, there had been no serious injuries, but a trip to Belfast for repairs was required, with the result that construction on the Titanic temporarily halted for a few days, tightening the preparation time allowed for the maiden voyage. Andrews himself did not doubt that ‘the ship will clean up all right before sailing on Wednesday’, but with the door hinges and paint still being applied to the Titanic’s Parisian-style café on Wednesday morning, White Star had ordered in vast quantities of fresh flowers which went straight into Titanic’s cold storage to be brought out over the course of the voyage to disguise any lingering smell of varnish.[5] Fixtures in some of the second-class lavatories needed to be attached, furniture bought from firms in England had to be delivered, the furniture in the Café Parisian still was not the right shade of green, and the pebbledashing in two of First Class’s most expensive private suites was too dark.[6] Andrews had overseen everything he could. His secretary, Thompson Hamilton, who had joined him from Belfast for the week, noticed, ‘He would himself put in their place such things as racks, tables, chairs, berth ladders, electric fans, saying that except he saw everything right he could not be satisfied.’[7] Meanwhile, a hose was working away on the contained fire in one of Boiler Room 5’s coal bunkers, with the source expected to be extinguished in the next few days.[8] By the evening of the 9th, everything of note had apparently been taken care of and Andrews could write to his wife, ‘The Titanic is now about complete and will I think do the old Firm credit to-morrow when we sail.’[9]

With their tasks accomplished, Andrews said a temporary farewell to colleagues, like Edward Wilding, whose work on Titanic ended in Southampton, and his secretary, Thompson Hamilton, who was travelling back to Belfast to handle any correspondence during Andrews’ absence. ‘Remember now,’ Andrews told Hamilton, with that second word ubiquitous to an Ulster dialect, ‘and keep Mrs Andrews informed of any news of the vessel.’[10] From the deck, Andrews could see other ships, moored together in greater numbers than usual. The British Miners’ Federation had voted to end a six-week strike only four days earlier and the impact on an industry as dependent on coal as shipping had been temporarily significant – many smaller liners had their voyages rescheduled to facilitate coal being reallocated for the on-time departures of the leviathans.[11] The red-, white- and blue-capped funnels of the American Line’s St Louis, Philadelphia and New York were moored next to White Star’s Majestic and Oceanic. After twenty-two years at sea, the Majestic had been withdrawn from regular service and designated a reserve ship, while the Philadelphia and New York were about to have their first-class quarters removed entirely for an increase of second- and third-class, as the drift of first-class clientele to larger, more modern ships had rendered them superfluous.[12] For Andrews, the most significant of the slumbering ships in the harbour was White Star’s former flagship, the Oceanic, berthed alongside the New York. After working his way up from his post-school apprenticeship at Harland and Wolff, Andrews had first been given charge of a design for the White Star Line in the late 1890s, helping to produce the Oceanic, praised then and later as a ‘ship of outstanding elegance both inside and out’.[13] The Oceanic was still in service in April 1912, but shipbuilding’s technological strides in the thirteen years since her debut had left that pretty ship far behind; the Titanic was nearly three times heavier than Andrews’ first ship, with room for almost twice as many passengers and crew.

Far below, the process of boarding the third-class passengers began shortly after the crew’s muster was completed. Since many in Third Class travelled as emigrating families, there were usually more children, necessitating a longer boarding process, combined with the delay-inducing medical inspections required by American immigration authorities.[14] Those on the dock that day were a few hundred of the 23,000 immigrants who would sail on White Star ships to America over the course of 1912–13.[15] Although it was, and is, often used to describe this collective, the word ‘steerage’ did not apply to those in Titanic’s Third Class. The noun sprang from the earlier days of mass migration to the United States and it could still in 1912 apply to the cheaper class of accommodation offered by other, often less prestigious travel companies, but there was an appreciable difference. Hamburg-Amerika’s soon to be launched Imperator would provide four classes of travel, delineating Third and Steerage as two different sections of the ship.[16] To qualify as steerage, there had to be communal dormitories, something that the Titanic did not offer. Every third-class passenger was in a cabin, albeit with bunk beds and, if travelling on their own, typically shared with others of their own gender. The White Star Line had a reputation for offering the best third-class accommodation then available, with the result that tickets on the Titanic or the Olympic could cost as much as Second Class on other liners.[17] Thus a contemporary travel guide could confidently assert that the White Star Line carried ‘a better class of emigrant’.[18]