Полная версия

Полная версияLove's Meinie: Three Lectures on Greek and English Birds

I do not find him named in the list of Cretan birds; but even if often seen, his dim red breast was little likely to make much impression on the Greeks, who knew the flamingo, and had made it, under the name of Phœnix or Phœnicopterus, the center of their myths of scarlet birds. They broadly embraced the general aspect of the smaller and more obscure species, under the term ξονθος [Greek: xonthos], which, as I understand their use of it, exactly implies the indescribable silky brown, the groundwork of all other color in so many small birds, which is indistinct among green leaves, and absolutely identifies itself with dead ones, or with mossy stems.

19. I think I show it you more accurately in the robin's back than I could in any other bird; its mode of transition into more brilliant color is, in him, elementarily simple; and although there is nothing, or rather because there is nothing, in his plumage, of interest like that of tropical birds, or even of our own game-birds, I think it will be desirable for you to learn first from the breast of the robin what a feather is. Once knowing that, thoroughly, we can further learn from the swallow what a wing is; from the chough what a beak is; and from the falcon what a claw is.

I must take care, however, in neither of these last two particulars, to do injustice to our little English friend here; and before we come to his feathers, must ask you to look at his bill and his feet.

20. I do not think it is distinctly enough felt by us that the beak of a bird is not only its mouth, but its hand, or rather its two hands. For, as its arms and hands are turned into wings, all it has to depend upon, in economical and practical life, is its beak. The beak, therefore, is at once its sword, its carpenter's tool-box, and its dressing-case; partly also its musical instrument; all this besides its function of seizing and preparing the food, in which functions alone it has to be a trap, carving-knife, and teeth, all in one.

21. It is this need of the beak's being a mechanical tool which chiefly regulates the form of a bird's face, as opposed to a four-footed animal's. If the question of food were the only one, we might wonder why there were not more four-footed creatures living on seeds than there are; or why those that do—field-mice and the like—have not beaks instead of teeth. But the fact is that a bird's beak is by no means a perfect eating or food-seizing instrument. A squirrel is far more dexterous with a nut than a cockatoo; and a dog manages a bone incomparably better than an eagle. But the beak has to do so much more! Pruning feathers, building nests, and the incessant discipline in military arts, are all to be thought of, as much as feeding.

Soldiership, especially, is a much more imperious necessity among birds than quadrupeds. Neither lions nor wolves habitually use claws or teeth in contest with their own species; but birds, for their partners, their nests, their hunting-grounds, and their personal dignity, are nearly always in contention; their courage is unequaled by that of any other race of animals capable of comprehending danger; and their pertinacity and endurance have, in all ages, made them an example to the brave, and an amusement to the base, among mankind.

22. Nevertheless, since as sword, as trowel, or as pocket-comb, the beak of the bird has to be pointed, the collection of seeds may be conveniently intrusted to this otherwise penetrative instrument, and such food as can only be obtained by probing crevices, splitting open fissures, or neatly and minutely picking things up, is allotted, pre-eminently, to the bird species.

The food of the robin, as you know, is very miscellaneous. Linnæus says of the Swedish one, that it is "delectatus euonymi baccis,"—"delighted with dogwood berries,"—the dogwood growing abundantly in Sweden, as once in Forfarshire, where it grew, though only a bush usually in the south, with trunks a foot or eighteen inches in diameter, and the tree thirty feet high. But the Swedish robin's taste for its berries is to be noted by you, because, first, the dogwood berry is commonly said to be so bitter that it is not eaten by birds (Loudon, "Arboretum," ii., 497, 1.); and, secondly, because it is a pretty coincidence that this most familiar of household birds should feed fondly from the tree which gives the housewife her spindle,—the proper name of the dogwood in English, French, and German being alike "Spindle-tree." It feeds, however, with us, certainly, most on worms and insects. I am not sure how far the following account of its mode of dressing its dinners may be depended on: I take it from an old book on Natural History, but find it, more or less, confirmed by others: "It takes a worm by one extremity in its beak, and beats it on the ground till the inner part comes away. Then seizing it in a similar manner by the other end, it entirely cleanses the outer part, which alone it eats."

One's first impression is that this must be a singularly unpleasant operation for the worm, however fastidiously delicate and exemplary in the robin. But I suppose the real meaning is, that as a worm lives by passing earth through its body, the robin merely compels it to quit this—not ill-gotten, indeed, but now quite unnecessary—wealth. We human creatures, who have lived the lives of worms, collecting dust, are served by Death in exactly the same manner.

23. You will find that the robin's beak, then, is a very prettily representative one of general bird power. As a weapon, it is very formidable indeed; he can kill an adversary of his own kind with one blow of it in the throat; and is so pugnacious, "valde pugnax," says Linnæus, "ut non una arbor duos capiat erithacos,"—"no single tree can hold two cock-robins;" and for precision of seizure, the little flat hook at the end of the upper mandible is one of the most delicately formed points of forceps which you can find among the grain eaters. But I pass to one of his more special perfections.

24. He is very notable in the exquisite silence and precision of his movements, as opposed to birds who either creak in flying, or waddle in walking. "Always quiet," says Gould, "for the silkiness of his plumage renders his movements noiseless, and the rustling of his wings is never heard, any more than his tread on earth, over which he bounds with amazing sprightliness." You know how much importance I have always given, among the fine arts, to good dancing. If you think of it, you will find one of the robin's very chief ingratiatory faculties is his dainty and delicate movement,—his footing it featly here and there. Whatever prettiness there may be in his red breast, at his brightest he can always be outshone by a brickbat. But if he is rationally proud of anything about him, I should think a robin must be proud of his legs. Hundreds of birds have longer and more imposing ones—but for real neatness, finish, and precision of action, commend me to his fine little ankles, and fine little feet; this long stilted process, as you know, corresponding to our ankle-bone. Commend me, I say, to the robin for use of his ankles—he is, of all birds, the pre-eminent and characteristic Hopper; none other so light, so pert, or so swift.

25. We must not, however, give too much credit to his legs in this matter. A robin's hop is half a flight; he hops, very essentially, with wings and tail, as well as with his feet, and the exquisitely rapid opening and quivering of the tail-feathers certainly give half the force to his leap. It is in this action that he is put among the motacillae, or wagtails; but the ornithologists have no real business to put him among them. The swing of the long tail feathers in the true wagtail is entirely consequent on its motion, not impulsive of it—the tremulous shake is after alighting. But the robin leaps with wing, tail, and foot, all in time, and all helping each other. Leaps, I say; and you check at the word; and ought to check: you look at a bird hopping, and the motion is so much a matter of course, you never think how it is done. But do you think you would find it easy to hop like a robin if you had two—all but wooden—legs, like this?

26. I have looked wholly in vain through all my books on birds, to find some account of the muscles it uses in hopping, and of the part of the toes with which the spring is given. I must leave you to find out that for yourselves; it is a little bit of anatomy which I think it highly desirable for you to know, but which it is not my business to teach you. Only observe, this is the point to be made out. You leap yourselves, with the toe and ball of the foot; but, in that power of leaping, you lose the faculty of grasp; on the contrary, with your hands, you grasp as a bird with its feet. But you cannot hop on your hands. A cat, a leopard, and a monkey, leap or grasp with equal ease; but the action of their paws in leaping is, I imagine, from the fleshy ball of the foot; while in the bird, characteristically γαμφωνυξ [Greek: gampsônux], this fleshy ball is reduced to a boss or series of bosses, and the nails are elongated into sickles or horns; nor does the springing power seem to depend on the development of the bosses. They are far more developed in an eagle than a robin; but you know how unpardonably and preposterously awkward an eagle is when he hops. When they are most of all developed, the bird walks, runs, and digs well, but leaps badly.

27. I have no time to speak of the various forms of the ankle itself, or of the scales of armor, more apparent than real, by which the foot and ankle are protected. The use of this lecture is not either to describe or to exhibit these varieties to you, but so to awaken your attention to the real points of character, that, when you have a bird's foot to draw, you may do so with intelligence and pleasure, knowing whether you want to express force, grasp, or firm ground pressure, or dexterity and tact in motion. And as the actions of the foot and the hand in man are made by every great painter perfectly expressive of the character of mind, so the expressions of rapacity, cruelty, or force of seizure, in the harpy, the gryphon, and the hooked and clawed evil spirits of early religious art, can only be felt by extreme attention to the original form.

28. And now I return to our main question, for the robin's breast to answer, "What is a feather?" You know something about it already; that it is composed of a quill, with its lateral filaments terminating generally, more or less, in a point; that these extremities of the quills, lying over each other like the tiles of a house, allow the wind and rain to pass over them with the least possible resistance, and form a protection alike from the heat and the cold; which, in structure much resembling the scale-armor assumed by man for very different objects, is, in fact, intermediate, exactly, between the fur of beasts and the scales of fishes; having the minute division of the one, and the armor-like symmetry and succession of the other.

29. Not merely symmetry, observe, but extreme flatness. Feathers are smoothed down, as a field of corn by wind with rain; only the swathes laid in beautiful order. They are fur, so structurally placed as to imply, and submit to, the perpetually swift forward motion. In fact, I have no doubt the Darwinian theory on the subject is that the feathers of birds once stuck up all erect, like the bristles of a brush, and have only been blown flat by continual flying.

Nay, we might even sufficiently represent the general manner of conclusion in the Darwinian system by the statement that if you fasten a hair-brush to a mill-wheel, with the handle forward, so as to develop itself into a neck by moving always in the same direction, and within continual hearing of a steam-whistle, after a certain number of revolutions the hair-brush will fall in love with the whistle; they will marry, lay an egg, and the produce will be a nightingale.

30. Whether, however, a hog's bristle can turn into a feather or not, it is vital that you should know the present difference between them.

The scientific people will tell you that a feather is composed of three parts—the down, the laminæ, and the shaft.

But the common-sense method of stating the matter is that a feather is composed of two parts, a shaft with lateral filaments. For the greater part of the shaft's length, these filaments are strong and nearly straight, forming, by their attachment, a finely warped sail, like that of a wind-mill. But towards the root of the feather they suddenly become weak, and confusedly flexible, and form the close down which immediately protects the bird's body.

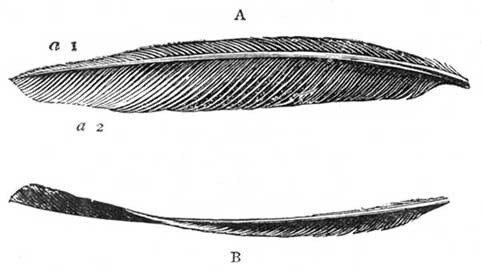

To show you the typical arrangement of these parts, I choose, as I have said, the robin; because, both in his power of flying, and in his color, he is a moderate and balanced bird;—not turned into nothing but wings, like a swallow, or nothing but neck and tail, like a peacock. And first for his flying power. There is one of the long feathers of robin's wing, and here (Fig. 1) the analysis of its form.

31. First, in pure outline (A), seen from above, it is very nearly a long oval, but with this peculiarity, that it has, as it were, projecting shoulders at a 1 and a 2. I merely desire you to observe this, in passing, because one usually thinks of the contour as sweeping unbroken from the root to the point. I have not time to-day to enter on any discussion of the reason for it, which will appear when we examine the placing of the wing feathers for their stroke.

Now, I hope you are getting accustomed to the general method in which I give you the analysis of all forms—leaf, or feather, or shell, or limb. First, the plan; then the profile; then the cross-section.

I take next, the profile of my feather (B, Fig. 1), and find that it is twisted as the sail of a windmill is, but more distinctly, so that you can always see the upper surface of the feather at its root, and the under at its end. Every primary wing-feather, in the fine flyers, is thus twisted; and is best described as a sail striking with the power of a cimeter, but with the flat instead of the edge.

Fig. 1.

(Twice the size of reality.)

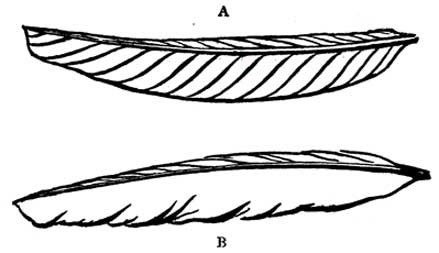

32. Further, you remember that on the edges of the broad side of feathers you find always a series of undulations, irregularly sequent, and lapping over each other like waves on sand. You might at first imagine that this appearance was owing to a slight ruffling or disorder of the filaments; but it is entirely normal, and, I doubt not, so constructed, in order to insure a redundance of material in the plume, so that no accident or pressure from wind may leave a gap anywhere. How this redundance is obtained you will see in a moment by bending any feather the wrong way. Bend, for instance, this plume, B, Fig. 2, into the reversed curve, A, Fig. 2; then all the filaments of the plume become perfectly even, and there are no waves at the edge. But let the plume return into its proper form, B, and the tissue being now contracted into a smaller space, the edge waves are formed in it instantly.

Fig. 2.

Hitherto, I have been speaking only of the filaments arranged for the strength and continuity of the energetic plume; they are entirely different when they are set together for decoration instead of force. After the feather of the robin's wing, let us examine one from his breast.

33. I said, just now, he might be at once outshone by a brickbat. Indeed, the day before yesterday, sleeping at Lichfield, and seeing, the first thing when I woke in the morning, (for I never put down the blinds of my bedroom windows,) the not uncommon sight in an English country town of an entire house-front of very neat, and very flat, and very red bricks, with very exactly squared square windows in it; and not feeling myself in anywise gratified or improved by the spectacle, I was thinking how in this, as in all other good, the too much destroyed all. The breadth of a robin's breast in brick-red is delicious, but a whole house-front of brick-red as vivid, is alarming. And yet one cannot generalize even that trite moral with any safety—for infinite breadth of green is delightful, however green; and of sea or sky, however blue.

You must note, however, that the robin's charm is greatly helped by the pretty space of gray plumage which separates the red from the brown back, and sets it off to its best advantage. There is no great brilliancy in it, even so relieved; only the finish of it is exquisite.

34. If you separate a single feather, you will find it more like a transparent hollow shell than a feather (so delicately rounded the surface of it),—gray at the root, where the down is,—tinged, and only tinged, with red at the part that overlaps and is visible; so that, when three or four more feathers have overlapped it again, all together, with their joined red, are just enough to give the color determined upon, each of them contributing a tinge. There are about thirty of these glowing filaments on each side, (the whole being no larger across than a well-grown currant,) and each of these is itself another exquisite feather, with central quill and lateral webs, whose filaments are not to be counted.

The extremity of these breast plumes parts slightly into two, as you see in the peacock's, and many other such decorative ones. The transition from the entirely leaf-like shape of the active plume, with its oblique point, to the more or less symmetrical dualism of the decorative plume, corresponds with the change from the pointed green leaf to the dual, or heart-shaped, petal of many flowers. I shall return to this part of our subject, having given you, I believe, enough of detail for the present.

35. I have said nothing to-day of the mythology of the bird, though I told you that would always be, for us, the most important part of its natural history. But I am obliged, sometimes, to take what we immediately want, rather than what, ultimately, we shall need chiefly. In the second place, you probably, most of you, know more of the mythology of the robin than I do, for the stories about it are all northern, and I know scarcely any myths but the Italian and Greek. You will find under the name "Robin," in Miss Yonge's exhaustive and admirable "History of Christian Names," the various titles of honor and endearment connected with him, and with the general idea of redness,—from the bishop called "Bright Red Fame," who founded the first great Christian church on the Rhine, (I am afraid of your thinking I mean a pun, in connection with robins, if I tell you the locality of it,) down through the Hoods, and Roys, and Grays, to Robin Goodfellow, and Spenser's "Hobbinol," and our modern "Hob,"—joining on to the "goblin," which comes from the old Greek Κοβαλος [Greek: Kobalos]. But I cannot let you go without asking you to compare the English and French feeling about small birds, in Chaucer's time, with our own on the same subject. I say English and French, because the original French of the Romance of the Rose shows more affection for birds than even Chaucer's translation, passionate as he is, always, in love for any one of his little winged brothers or sisters. Look, however, either in the French or English at the description of the coming of the God of Love, leading his carol-dance, in the garden of the Rose.

His dress is embroidered with figures of flowers and of beasts; but about him fly the living birds. The French is:

Il etoit tout convert d'oisiaulxDe rossignols et de papegauxDe calendre, et de mesangel.Il semblait que ce fut une angleQui fuz tout droit venuz du ciel.36. There are several points of philology in this transitional French, and in Chaucer's translation, which it is well worth your patience to observe. The monkish Latin "angelus," you see, is passing through the very unpoetical form "angle," into "ange;" but, in order to get a rhyme with it in that angular form, the French troubadour expands the bird's name, "mesange," quite arbitrarily, into "mesangel." Then Chaucer, not liking the "mes" at the beginning of the word, changes that unscrupulously into "arch;" and gathers in, though too shortly, a lovely bit from another place about the nightingales flying so close round Love's head that they strike some of the leaves off his crown of roses; so that the English runs thus:

But nightingales, a full great routThat flien over his head about,The leaves felden as they flienAnd he was all with birds wrien,With popinjay, with nightingale,With chelaundre, and with wodewale,With finch, with lark, and with archangel.He seemed as he were an angell,That down were comen from Heaven clear.Now, when I first read this bit of Chaucer, without referring to the original, I was greatly delighted to find that there was a bird in his time called an archangel, and set to work, with brightly hopeful industry, to find out what it was. I was a little discomfited by finding that in old botany the word only meant "dead-nettle," but was still sanguine about my bird, till I found the French form descend, as you have seen, into a mesangel, and finally into mesange, which is a provincialism from μειον [Greek: meion], and means, the smallest of birds—or, specially here,—a titmouse. I have seldom had a less expected or more ignominious fall from the clouds.

37. The other birds, named here and in the previous description of the garden, are introduced, as far as I can judge, nearly at random, and with no precision of imagination like that of Aristophanes; but with a sweet childish delight in crowding as many birds as possible into the smallest space. The popinjay is always prominent; and I want some of you to help me (for I have not time at present for the chase) in hunting the parrot down on his first appearance in Europe. Just at this particular time he contested favor even with the falcon; and I think it a piece of good fortune that I chanced to draw for you, thinking only of its brilliant color, the popinjay, which Carpaccio allows to be present on the grave occasion of St. George's baptizing the princess and her father.

38. And, indeed, as soon as the Christian poets begin to speak of the singing of the birds, they show themselves in quite a different mood from any that ever occurs to a Greek. Aristophanes, with infinitely more skill, describes, and partly imitates, the singing of the nightingale; but simply as beautiful sound. It "fills the thickets with honey;" and if in the often-quoted—just because it is not characteristic of Greek literature—passage of the Coloneus, a deeper sentiment is shown, that feeling is dependent on association of the bird-voices with deeply pathetic circumstances. But this troubadour finds his heart in heaven by the power of the singing only:—

Trop parfoisaient beau serviseCiz oiselles que je vous devise.Il chantaient un chant ytelCom fussent angle esperitel.We want a moment more of word-chasing to enjoy this. "Oiseau," as you know, comes from "avis;" but it had at this time got "oisel" for its singular number, of which the terminating "sel" confused itself with the "selle," from "ancilla" in domisella and demoiselle; and the feminine form "oiselle" thus snatched for itself some of the delightfulness belonging to the title of a young lady. Then note that "esperitel" does not here mean merely spiritual, (because all angels are spiritual) but an "angle esperitel" is an angel of the air. So that, in English, we could only express the meaning in some such fashion as this:—

They perfected all their service of love,These maiden birds that I tell you of.They sang such a song, so finished-fair,As if they were angels, born of the air.39. Such were the fancies, then, and the scenes, in which Englishmen took delight in Chaucer's time. England was then a simple country; we boasted, for the best kind of riches, our birds and trees, and our wives and children. We had now grown to be a rich one; and our first pleasure is in shooting our birds; but it has become too expensive for us to keep our trees. Lord Derby, whose crest is the eagle and child—you will find the northern name for it, the bird and bantling, made classical by Scott—is the first to propose that wood-birds should have no more nests. We must cut down all our trees, he says, that we may effectively use the steam-plow; and the effect of the steam-plow, I find by a recent article in the Cornhill Magazine, is that an English laborer must not any more have a nest, nor bantlings, neither; but may only expect to get on prosperously in life, if he be perfectly skillful, sober, and honest, and dispenses, at least until he is forty-five, with the "luxury of marriage."