Полная версия

Полная версияAriadne Florentina: Six Lectures on Wood and Metal Engraving

"HE THAT HATH EARS TO HEAR, LET HIM HEAR."

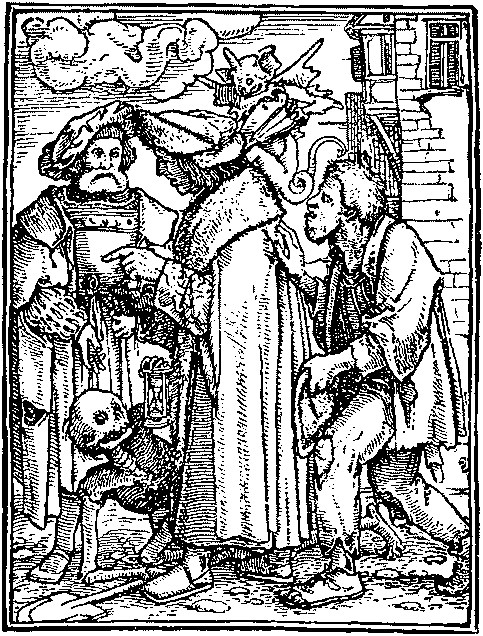

(Fig. 6) Facsimile from Holbein's woodcut.

176. Again: there was not in the old creed any subject more definitely and constantly insisted on than the death of a miser. He had been happy, the old preachers thought, till then: but his hour has come; and the black covetousness of hell is awake and watching; the sharp harpy claws will clutch his soul out of his mouth, and scatter his treasure for others. So the commonplace preacher and painter taught. Not so Holbein. The devil want to snatch his soul, indeed! Nay, he never had a soul, but of the devil's giving. His misery to begin on his death-bed! Nay, he had never an unmiserable hour of life. The fiend is with him now,—a paltry, abortive fiend, with no breath even to blow hot with. He supplies the hell-blast with a machine. It is winter, and the rich man has his furred cloak and cap, thick and heavy; the beggar, bare-headed to beseech him, skin and rags hanging about him together, touches his shoulder, but all in vain; there is other business in hand. More haggard than the beggar himself, wasted and palsied, the rich man counts with his fingers the gain of the years to come.

But of those years, infinite that are to be, Holbein says nothing. 'I know not; I see not. This only I see, on this very winter's day, the low pale stumbling-block at your feet, the altogether by you unseen and forgotten Death. You shall not pass him by on the other side; here is a fasting figure in skin and bone, at last, that will stop you; and for all the hidden treasures of earth, here is your spade: dig now, and find them.'

177. I have said that Holbein was condemned to teach these things. He was not happy in teaching them, nor thanked for teaching them. Nor was Botticelli for his lovelier teaching. But they both could do no otherwise. They lived in truth and steadfastness; and with both, in their marvelous design, veracity is the beginning of invention, and love its end.

I have but time to show you, in conclusion, how this affectionate self-forgetfulness protects Holbein from the chief calamity of the German temper, vanity, which is at the root of all Dürer's weakness. Here is a photograph of Holbein's portrait of Erasmus, and a fine proof of Dürer's. In Holbein's, the face leads everything; and the most lovely qualities of the face lead in that. The cloak and cap are perfectly painted, just because you look at them neither more nor less than you would have looked at the cloak in reality. You don't say, 'How brilliantly they are touched,' as you would with Rembrandt; nor 'How gracefully they are neglected,' as you would with Gainsborough; nor 'How exquisitely they are shaded,' as you would with Lionardo; nor 'How grandly they are composed,' as you would with Titian. You say only, 'Erasmus is surely there; and what a pleasant sight!' You don't think of Holbein at all. He has not even put in the minutest letter H, that I can see, to remind you of him. Drops his H's, I regret to say, often enough. 'My hand should be enough for you; what matters my name?' But now, look at Dürer's. The very first thing you see, and at any distance, is this great square tablet with

"The image of Erasmus, drawn from the life by Albert Dürer, 1526,"

and a great straddling a.d. besides. Then you see a cloak, and a table, and a pot, with flowers in it, and a heap of books with all their leaves and all their clasps, and all the little bits of leather gummed in to mark the places; and last of all you see Erasmus's face; and when you do see it, the most of it is wrinkles.

All egotism and insanity, this, gentlemen. Hard words to use; but not too hard to define the faults which rendered so much of Dürer's great genius abortive, and to this day paralyze, among the details of a lifeless and ambitious precision, the student, no less than the artist, of German blood. For too many an Erasmus, too many a Dürer, among them, the world is all cloak and clasp, instead of face or book; and the first object of their lives is to engrave their initials.

178. For us, in England, not even so much is at present to be hoped; and yet, singularly enough, it is more our modesty, unwisely submissive, than our vanity, which has destroyed our English school of engraving.

At the bottom of the pretty line engravings which used to represent, characteristically, our English skill, one saw always two inscriptions. At the left-hand corner, "Drawn by—so-and-so;" at the right-hand corner, "Engraved by—so-and-so." Only under the worst and cheapest plates—for the Stationers' Almanack, or the like—one saw sometimes, "Drawn and engraved by—so-and-so," which meant nothing more than that the publisher would not go to the expense of an artist, and that the engraver haggled through as he could. (One fortunate exception, gentlemen, you have in the old drawings for your Oxford Almanack, though the publishers, I have no doubt, even in that case, employed the cheapest artist they could find.43) But in general, no engraver thought himself able to draw; and no artist thought it his business to engrave.

179. But the fact that this and the following lecture are on the subject of design in engraving, implies of course that in the work we have to examine, it was often the engraver himself who designed, and as often the artist who engraved.

And you will observe that the only engravings which bear imperishable value are, indeed, in this kind. It is true that, in wood-cutting, both Dürer and Holbein, as in our own days Leech and Tenniel, have workmen under them who can do all they want. But in metal cutting it is not so. For, as I have told you, in metal cutting, ultimate perfection of Line has to be reached; and it can be reached by none but a master's hand; nor by his, unless in the very moment and act of designing. Never, unless under the vivid first force of imagination and intellect, can the Line have its full value. And for this high reason, gentlemen, that paradox which perhaps seemed to you so daring, is nevertheless deeply and finally true, that while a woodcut may be laboriously finished, a grand engraving on metal must be comparatively incomplete. For it must be done, throughout, with the full fire of temper in it, visibly governing its lines, as the wind does the fibers of cloud.

180. The value hitherto attached to Rembrandt's etchings, and others imitating them, depends on a true instinct in the public mind for this virtue of line. But etching is an indolent and blundering method at the best; and I do not doubt that you will one day be grateful for the severe disciplines of drawing required in these schools, in that they will have enabled you to know what a line may be, driven by a master's chisel on silver or marble, following, and fostering as it follows, the instantaneous strength of his determined thought.

LECTURE VI

DESIGN IN THE FLORENTINE SCHOOLS OF ENGRAVING181. In the first of these lectures, I stated to you their subject, as the investigation of the engraved work of a group of men, to whom engraving, as a means of popular address, was above all precious, because their art was distinctively didactic.

Some of my hearers must be aware that, of late years, the assertion that art should be didactic has been clamorously and violently derided by the countless crowd of artists who have nothing to represent, and of writers who have nothing to say; and that the contrary assertion—that art consists only in pretty colors and fine words,—is accepted, readily enough, by a public which rarely pauses to look at a picture with attention, or read a sentence with understanding.

182. Gentlemen, believe me, there never was any great advancing art yet, nor can be, without didactic purpose. The leaders of the strong schools are, and must be always, either teachers of theology, or preachers of the moral law. I need not tell you that it was as teachers of theology on the walls of the Vatican that the masters with whose names you are most familiar obtained their perpetual fame. But however great their fame, you have not practically, I imagine, ever been materially assisted in your preparation for the schools either of philosophy or divinity by Raphael's 'School of Athens,' by Raphael's 'Theology,'—or by Michael Angelo's 'Judgment.' My task, to-day, is to set before you some part of the design of the first Master of the works in the Sistine Chapel; and I believe that, from his teaching, you will, even in the hour which I ask you now to give, learn what may be of true use to you in all your future labor, whether in Oxford or elsewhere.

183. You have doubtless, in the course of these lectures, been occasionally surprised by my speaking of Holbein and Sandro Botticelli, as Reformers, in the same tone of respect, and with the same implied assertion of their intellectual power and agency, with which it is usual to speak of Luther and Savonarola. You have been accustomed, indeed, to hear painting and sculpture spoken of as supporting or enforcing Church doctrine; but never as reforming or chastising it. Whether Protestant or Roman Catholic, you have admitted what in the one case you held to be the abuse of painting in the furtherance of idolatry,—in the other, its amiable and exalting ministry to the feebleness of faith. But neither has recognized,—the Protestant his ally,—or the Catholic his enemy, in the far more earnest work of the great painters of the fifteenth century. The Protestant was, in most cases, too vulgar to understand the aid offered to him by painting; and in all cases too terrified to believe in it. He drove the gift-bringing Greek with imprecations from his sectarian fortress, or received him within it only on the condition that he should speak no word of religion there.

184. On the other hand, the Catholic, in most cases too indolent to read, and, in all, too proud to dread, the rebuke of the reforming painters, confused them with the crowd of his old flatterers, and little noticed their altered language or their graver brow. In a little while, finding they had ceased to be amusing, he effaced their works, not as dangerous, but as dull; and recognized only thenceforward, as art, the innocuous bombast of Michael Angelo, and fluent efflorescence of Bernini. But when you become more intimately and impartially acquainted with the history of the Reformation, you will find that, as surely and earnestly as Memling and Giotto strove in the north and south to set forth and exalt the Catholic faith, so surely and earnestly did Holbein and Botticelli strive, in the north, to chastise, and, in the south, to revive it. In what manner, I will try to-day briefly to show you.

185. I name these two men as the reforming leaders: there were many, rank and file, who worked in alliance with Holbein; with Botticelli, two great ones, Lippi and Perugino. But both of these had so much pleasure in their own pictorial faculty, that they strove to keep quiet, and out of harm's way,—involuntarily manifesting themselves sometimes, however; and not in the wisest manner. Lippi's running away with a novice was not likely to be understood as a step in Church reformation correspondent to Luther's marriage.44 Nor have Protestant divines, even to this day, recognized the real meaning of the reports of Perugino's 'infidelity.' Botticelli, the pupil of the one, and the companion of the other, held the truths they taught him through sorrow as well as joy; and he is the greatest of the reformers, because he preached without blame; though the least known, because he died without victory.

I had hoped to be able to lay before you some better biography of him than the traditions of Vasari, of which I gave a short abstract some time back in Fors Clavigera (Letter XXII.); but as yet I have only added internal evidence to the popular story, the more important points of which I must review briefly. It will not waste your time if I read,—instead of merely giving you reference to,—the passages on which I must comment.

186. "His father, Mariano Filipepi, a Florentine citizen, brought him up with care, and caused him to be instructed in all such things as are usually taught to children before they choose a calling. But although the boy readily acquired whatever he wished to learn, yet was he constantly discontented; neither would he take any pleasure in reading, writing, or accounts, insomuch that the father, disturbed by the eccentric habits of his son, turned him over in despair to a gossip of his, called Botticello, who was a goldsmith, and considered a very competent master of his art, to the intent that the boy might learn the same."

"He took no pleasure in reading, writing, nor accounts"! You will find the same thing recorded of Cimabue; but it is more curious when stated of a man whom I cite to you as typically a gentleman and a scholar. But remember, in those days, though there were not so many entirely correct books issued by the Religious Tract Society for boys to read, there were a great many more pretty things in the world for boys to see. The Val d'Arno was Pater-noster Row to purpose; their Father's Row, with books of His writing on the mountain shelves. And the lad takes to looking at things, and thinking about them, instead of reading about them,—which I commend to you also, as much the more scholarly practice of the two. To the end, though he knows all about the celestial hierarchies, he is not strong in his letters, nor in his dialect. I asked Mr. Tyrwhitt to help me through with a bit of his Italian the other day. Mr. Tyrwhitt could only help me by suggesting that it was "Botticelli for so-and-so." And one of the minor reasons which induced me so boldly to attribute these sibyls to him, instead of Bandini, is that the lettering is so ill done. The engraver would assuredly have had his lettering all right,—or at least neat. Botticelli blunders through it, scratches impatiently out when he goes wrong: and as I told you there's no repentance in the engraver's trade, leaves all the blunders visible.

187. I may add one fact bearing on this question lately communicated to me.45 In the autumn of 1872 I possessed myself of an Italian book of pen drawings, some, I have no doubt, by Mantegna in his youth, others by Sandro himself. In examining these, I was continually struck by the comparatively feeble and blundering way in which the titles were written, while all the rest of the handling was really superb; and still more surprised when, on the sleeves and hem of the robe of one of the principal figures of women, ("Helena rapita da Paris,") I found what seemed to be meant for inscriptions, intricately embroidered; which nevertheless, though beautifully drawn, I could not read. In copying Botticelli's Zipporah this spring, I found the border of her robe wrought with characters of the same kind, which a young painter, working with me, who already knows the minor secrets of Italian art better than I,46 assures me are letters,—and letters of a language hitherto undeciphered.

188. "There was at that time a close connection and almost constant intercourse between the goldsmiths and the painters, wherefore Sandro, who possessed considerable ingenuity, and was strongly disposed to the arts of design, became enamored of painting, and resolved to devote himself entirely to that vocation. He acknowledged his purpose at once to his father; and the latter, who knew the force of his inclination, took him accordingly to the Carmelite monk, Fra Filippo, who was a most excellent painter of that time, with whom he placed him to study the art, as Sandro himself had desired. Devoting himself thereupon entirely to the vocation he had chosen, Sandro so closely followed the directions, and imitated the manner, of his master, that Fra Filippo conceived a great love for him, and instructed him so effectually, that Sandro rapidly attained to such a degree in art as none would have predicted for him."

I have before pointed out to you the importance of training by the goldsmith. Sandro got more good of it, however, than any of the other painters so educated,—being enabled by it to use gold for light to color, in a glowing harmony never reached with equal perfection, and rarely attempted, in the later schools. To the last, his paintings are partly treated as work in niello; and he names himself, in perpetual gratitude, from this first artisan master. Nevertheless, the fortunate fellow finds, at the right moment, another, even more to his mind, and is obedient to him through his youth, as to the other through his childhood. And this master loves him; and instructs him 'so effectually,'—in grinding colors, do you suppose, only; or in laying of lines only; or in anything more than these?

189. I will tell you what Lippi must have taught any boy whom he loved. First, humility, and to live in joy and peace, injuring no man—if such innocence might be. Nothing is so manifest in every face by him, as its gentleness and rest. Secondly, to finish his work perfectly, and in such temper that the angels might say of it—not he himself—'Iste perfecit opus.' Do you remember what I told you in the Eagle's Nest (§ 53), that true humility was in hoping that angels might sometimes admire our work; not in hoping that we should ever be able to admire theirs? Thirdly,—a little thing it seems, but was a great one,—love of flowers. No one draws such lilies or such daisies as Lippi. Botticelli beat him afterwards in roses, but never in lilies. Fourthly, due honor for classical tradition. Lippi is the only religious painter who dresses John Baptist in the camelskin, as the Greeks dressed Heracles in the lion's—over the head. Lastly, and chiefly of all,—Le Père Hyacinthe taught his pupil certain views about the doctrine of the Church, which the boy thought of more deeply than his tutor, and that by a great deal; and Master Sandro presently got himself into such question for painting heresy, that if he had been as hot-headed as he was true-hearted, he would soon have come to bad end by the tar-barrel. But he is so sweet and so modest, that nobody is frightened; so clever, that everybody is pleased: and at last, actually the Pope sends for him to paint his own private chapel,—where the first thing my young gentleman does, mind you, is to paint the devil in a monk's dress, tempting Christ! The sauciest thing, out and out, done in the history of the Reformation, it seems to me; yet so wisely done, and with such true respect otherwise shown for what was sacred in the Church, that the Pope didn't mind: and all went on as merrily as marriage bells.

190. I have anticipated, however, in telling you this, the proper course of his biography, to which I now return.

"While still a youth he painted the figure of Fortitude, among those pictures of the Virtues which Antonio and Pietro Pollaiuolo were executing in the Mercatanzia, or Tribunal of Commerce, in Florence. In Santo Spirito, a church of the same city, he painted a picture for the chapel of the Bardi family: this work he executed with great diligence, and finished it very successfully, depicting certain olive and palm trees therein with extraordinary care."

It is by a beautiful chance that the first work of his, specified by his Italian biographer, should be the Fortitude.47 Note also what is said of his tree drawing.

"Having, in consequence of this work, obtained much credit and reputation, Sandro was appointed by the Guild of Porta Santa Maria to paint a picture in San Marco, the subject of which is the Coronation of Our Lady, who is surrounded by a choir of angels—the whole extremely well designed, and finished by the artist with infinite care. He executed various works in the Medici Palace for the elder Lorenzo, more particularly a figure of Pallas on a shield wreathed with vine branches, whence flames are proceeding: this he painted of the size of life. A San Sebastiano was also among the most remarkable of the works executed for Lorenzo. In the church of Santa Maria Maggiore, in Florence, is a Pietà, with small figures, by this master: this is a very beautiful work. For different houses in various parts of the city Sandro painted many pictures of a round form, with numerous figures of women undraped. Of these there are still two examples at Castello, a villa of the Duke Cosimo,—one representing the birth of Venus, who is borne to earth by the Loves and Zephyrs; the second also presenting the figure of Venus crowned with flowers by the Graces: she is here intended to denote the Spring, and the allegory is expressed by the painter with extraordinary grace."

Our young Reformer enters, it seems, on a very miscellaneous course of study; the Coronation of Our Lady; St. Sebastian; Pallas in vine-leaves; and Venus,—without fig-leaves. Not wholly Calvinistic, Fra Filippo's teaching seems to have been! All the better for the boy—being such a boy as he was: but I cannot in this lecture enter farther into my reasons for saying so.

191. Vasari, however, has shot far ahead in telling us of this picture of the Spring, which is one of Botticelli's completest works. Long before he was able to paint Greek nymphs, he had done his best in idealism of greater spirits; and, while yet quite a youth, painted, at Castello, the Assumption of Our Lady, with "the patriarchs, the prophets, the apostles, the evangelists, the martyrs, the confessors, the doctors, the virgins, and the hierarchies!"

Imagine this subject proposed to a young, (or even old) British Artist, for his next appeal to public sensation at the Academy! But do you suppose that the young British artist is wiser and more civilized than Lippi's scholar, because his only idea of a patriarch is of a man with a long beard; of a doctor, the M.D. with the brass plate over the way; and of a virgin, Miss – of the – theater?

Not that even Sandro was able, according to Vasari's report, to conduct the entire design himself. The proposer of the subject assisted him; and they made some modifications in the theology, which brought them both into trouble—so early did Sandro's innovating work begin, into which subjects our gossiping friend waives unnecessary inquiry, as follows.

"But although this picture is exceedingly beautiful, and ought to have put envy to shame, yet there were found certain malevolent and censorious persons who, not being able to affix any other blame to the work, declared that Matteo and Sandro had erred gravely in that matter, and had fallen into grievous heresy.

"Now, whether this be true or not, let none expect the judgment of that question from me: it shall suffice me to note that the figures executed by Sandro in that work are entirely worthy of praise; and that the pains he took in depicting those circles of the heavens must have been very great, to say nothing of the angels mingled with the other figures, or of the various foreshortenings, all which are designed in a very good manner.

"About this time Sandro received a commission to paint a small picture with figures three parts of a braccio high,—the subject an Adoration of the Magi.

"It is indeed a most admirable work; the composition, the design, and the coloring are so beautiful that every artist who examines it is astonished; and, at the time, it obtained so great a name in Florence, and other places, for the master, that Pope Sixtus IV. having erected the chapel built by him in his palace at Rome, and desiring to have it adorned with paintings, commanded that Sandro Botticelli should be appointed Superintendent of the work."

192. Vasari's words, "about this time," are evidently wrong. It must have been many and many a day after he painted Matteo's picture that he took such high standing in Florence as to receive the mastership of the works in the Pope's chapel at Rome. Of his position and doings there, I will tell you presently; meantime, let us complete the story of his life.

"By these works Botticelli obtained great honor and reputation among the many competitors who were laboring with him, whether Florentines or natives of other cities, and received from the Pope a considerable sum of money; but this he consumed and squandered totally, during his residence in Rome, where he lived without due care, as was his habit."

193. Well, but one would have liked to hear how he squandered his money, and whether he was without care—of other things than money.

It is just possible, Master Vasari, that Botticelli may have laid out his money at higher interest than you know of; meantime, he is advancing in life and thought, and becoming less and less comprehensible to his biographer. And at length, having got rid, somehow, of the money he received from the Pope; and finished the work he had to do, and uncovered it,—free in conscience, and empty in purse, he returned to Florence, where, "being a sophistical person, he made a comment on a part of Dante, and drew the Inferno, and put it in engraving, in which he consumed much time; and not working for this reason, brought infinite disorder into his affairs."