скачать книгу бесплатно

It’s the same on the pitch. I can hear certain sounds when the game slows down for a moment or two, like when I’m taking a corner or free-kick and there’s a strange rumble of 20,000 spring-loaded seats thwacking back in a section of the ground behind me as I stand over the ball, everyone on their feet, craning their necks to watch. But it’s never long before the muffled noise comes over again. Then I’m back underwater. Back in the bubble.

The ball’s coming my way.

The deflection has changed the shape of Nani’s pass, sending it higher than I thought, which buys me an extra second to shift into position and re-adjust my balance, to think: I’m having a go at this. My legs are knackered, but I use all the strength I have to spring from the back of my heels, swinging my right leg over my left shoulder in mid-air to bang the cross with an overhead kick, an acrobatic volley. It’s an all or nothing hit that I know will make me look really stupid if I spoon it.

But I don’t.

I make good contact with the ball and it fires into the top corner; I feel it, but I don’t see it. As I twist in mid-air, trying to follow the flight of my shot, I can’t see where the ball has gone, but the sudden roar of noise tells me I’ve scored. I roll over and see Joe Hart, City’s goalkeeper, rooted to the spot, his arms spread wide in disbelief, the ball bobbling and spinning in the net behind him.

If playing football is like being underwater, then scoring a goal feels like coming up for air.

I can see and hear it all, clear as anything. Faces in the crowd, thousands and thousands of them shouting and smiling, climbing over one another. Grown men jumping up and down like little kids. Children screaming with proper passion, flags waving. Every image is razor sharp. I see the colour of the stewards’ bibs in the stands. I can see banners hanging from the Stretford End: ‘For Every Manc A Religion’; ‘One Love’. It’s like going from black and white to colour; standard to high-definition telly at a push of the remote.

Everyone is going mental in the crowd; they think the game is just about won.

From nearly giving the ball away to smashing a winning goal into the top corner: it’s scary how fine the margins are in top-flight footy. The difference between winning and losing is on a knife edge a lot of the time. That’s why it’s the best game in the world.

*****

We close out the game 2–1. Everyone gathers round me in the dressing room afterwards, they want to talk about the goal. But I’m wrecked, done in, I’ve got nothing left; it’s all out there on the pitch, along with that overhead kick. The room is buzzing; Rio Ferdinand is buzzing.

‘Wow,’ he says.

Patrice Evra, our full-back, calls it ‘beautiful’.

Then The Manager comes into the dressing room, his big black coat on; he looks made up, excited. The man who has shouted, screamed and yelled from the Old Trafford touchlines for over a quarter of a century; the man who has managed and inspired some of the greatest players in Premier League history. The man who signed me for the biggest club in the world. The most successful club boss in the modern game.

He walks round to all of us and shakes our hands like he does after every win. It’s been like this since the day I signed for United. Thankfully I’ve had a lot of handshakes.

He lets on to me. ‘That was magnificent, Wayne, that was great.’

I nod; I’m too tired to speak, but I wouldn’t say anything if I could.

Don’t get me wrong, there’s nothing better than The Manager saying well done – but I don’t need it. I know when I’ve played well and when I’ve played badly. I don’t think, If The Manager says I’ve played well, I’ve played well. I know in my heart whether I have or I haven’t.

Then he makes out that it’s the best goal he’s ever seen at Old Trafford. He should know, he’s been around the club long enough and seen plenty of great goalscorers come and go during his time.

The Manager is in charge of everything and he controls the players at Manchester United emotionally and physically. Before the game he reads out the teamsheet and I sometimes get that same weird, nervous feeling I used to get whenever the coach of the school team pinned the starting XI to the noticeboard. During a match, if we’re a goal down but playing well, he tells us to keep going. He knows an equaliser is coming. He talks us into winning. Then again, I’ve known us to be winning by two or three goals at half-time and he’s gone nuts when we’ve sat down in the dressing room.

We’re winning. What’s up with him?

Then I cotton on.

He doesn’t want us to be complacent.

Like most managers he appreciates good football, but he appreciates winners more. His desire to win is greater than in anyone I’ve ever known, and it rubs off on all of us.

The funny thing is, I think we’re quite similar. We both have a massive determination to succeed and that has a lot to do with our upbringing – as kids we were told that if we wanted to do well we’d have to fight for it and graft. That’s the way I was brought up; I think it was the way he was brought up, too. And when we win something, like a Premier League title or the Champions League trophy, we’re stubborn enough to hang onto that success. That’s why we work so hard, so we can be the best for as long as possible.

Everyone begins to push and shove around a small telly in the corner of the room. It’s been sitting there for years and the coaches always turn it on to replay the game whenever there’s been a controversial incident or maybe a penalty shout that hasn’t been given – and there’s been a few of those, as The Manager will probably tell anyone who wants to listen. This time, I want to see my goal. Everyone does.

One of the coaches grabs the controls and forwards the action to the 77th minute.

I see my heavy touch, Scholesy’s pass to Nani.

I see his cross.

Then I watch, like it’s a weird out of body experience, as I throw myself up in the air and thump the ball into the back of the net. It doesn’t seem real.

I reckon all footballers go to bed and dream about scoring great goals: dribbling the ball around six players and popping it over the goalkeeper, or smashing one in from 25 yards. Scoring from a bicycle kick is one I’ve always fantasised about.

I’ve just scored a dream goal in a Manchester derby.

‘Wow,’ says Rio, for the second time, shaking his head.

I know what he means. I sit in the dressing room, still sweating, trying to live in the moment for as long as I can because these moments are so rare. I can still hear the United fans singing outside, giving it to the City lot, and I wonder if I’ll ever score a goal as good as that again.

*****

I’ve played in the Premier League for 10 years now. I’m probably in the middle of my career, which feels weird. The time has flown by so quickly. It does my head in a little, but I still reckon my best years are ahead of me, that there’s plenty more to come. It only seems like five minutes ago that I was making my debut for Everton against Tottenham in August 2002. The Spurs fans were tucked away in one end of Goodison Park. When I ran onto the pitch they started singing at me:

‘Who are ya?’

Whenever I touched the ball:

‘Who are ya?’

They don’t sing that at me anymore. They just boo and chuck abuse and slag me off instead. Funny that.

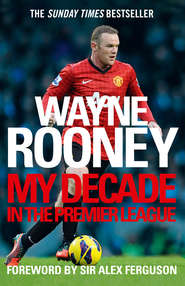

In the 10 years since my debut, I’ve done a hell of a lot. From 2002 to 2004 I played for Everton, the team I supported as a boy; I became the youngest player to represent England in 2003, before Arsenal’s Theo Walcott had that record off me. In 2004 I signed for Man United for a fee in excess of £25 million and became the club’s highest-ever Premier League goalscorer. During the European Championships that same year, the England players nicknamed me ‘Wazza’; the title seems to have stuck.

I’ve won four Premier League titles, a Champions League, two League Cups, three FA Community Shields and a FIFA Club World Cup. I’ve scored over 200 goals for club and country, and been sent off five times. I’d be lying if I told you that I haven’t loved every minute of it. Well, OK, maybe not the red cards and the suspensions, but everything else has been sound.

The funny thing is, the excitement and adrenaline I felt on the night before my league debut for Everton in 2002 still gets to me. The day before a game, home or away, always feels like Christmas Eve. When I go to bed I’ll wake up two or three times in the night and roll over to look at the alarm clock.

Gutted. It’s only two in the morning.

The buzz and the anticipation are there until the minute we kick off.

I’ve paid the price, though. Physically I’ve taken a bit of a battering over the years; being lumped by Transformer-sized centre-backs or having my muscles smashed by falls, shoulder barges and last-ditch tackles, day in, day out, has left me a bit bruised.

When I get up in the morning after a game, I struggle to walk for the first half an hour. I ache a bit. It wasn’t like that when I was a lad. I remember sometimes when I finished training or playing with Everton and United, I’d want to play some more. There was a small-sided pitch in my garden and I used to play in there with my mates. When I trained with Everton, I used to go for a game down the local leisure centre afterwards, or we used to play in the street in Croxteth, the area of Liverpool where I grew up with my mum, dad and younger brothers Graeme and John. There was a nursery facing my house. When it closed for the day, they’d bring some shutters down which made for a handy goal. I loved playing there. After I’d made my England debut in 2003 I was photographed kicking a ball against that nursery in a France shirt.

Footy has had a massive impact on my body because my game is based on speed and power. Intensity. As a striker I need to work hard all the time; I need to be sharp, which means my fitness has to be right to play well. If it isn’t, it shows. It would probably be different if I were a full-back; I could hide a bit, make fewer runs into the opposition’s half and get away with it. As a centre-forward for Manchester United, there’s no place to hide. I’ve got to work as hard as I can, otherwise The Manager will haul me off the pitch or drop me for the next game. There’s no room for failure or second best at this club.

If there is a downside to my life then it’s the pressure of living in the public eye. I’d like just for one day to have no-one know me at all, to do normal stuff; to be able to go to the shops and not have everyone stare and take pictures. Even just to be able to go for a night out with my mates and not have anyone point at me would be nice. On a weekend, some of my pals go to the betting shop before the matches start and put down a little bet – I’d love to be able to do that. But look, this is the small stuff, I’m grateful for everything that football has given me.

There is one small paranoia: like any player I’m fearful of getting a career-ending injury. I could be in the best form of my life and then one day a bad tackle might finish my time in the sport. It’s over then. But I think that’s the risk I take as a player in every match. I know football is such a short career that one day, at any age, the game could be snatched from me unexpectedly. But I want to decide when I leave football, not a physio, or an opponent’s boot.

Don’t get me wrong, the fear of injury or failure has never got into my head when I’ve been playing. I’ve never frozen on the football pitch. I’ve always wanted to express myself, I’ve always wanted to try things. I’ve never gone into a game worrying.

I hope we don’t lose this one.

What’s going to happen if we get beat?

I’ve always been confident that we’re going to win the game, whoever I’ve played for. I’ve never been short of belief in a game of footy.

I’m so confident, I’m happy to play anywhere on the pitch. I’ve offered to play centre-back when United have been hit by injuries; I’ve even offered to play full-back. I reckon I could go there and do a good job, no problem. I remember Edwin van der Sar once busted his nose against Spurs and had to go off. We didn’t have a reserve goalie and I thought about going in nets because I played there in training a few times and I’d done alright. Against Portsmouth in the FA Cup in 2008, our keeper Tomasz Kuszczak was sent off and I wanted to go in then, but The Manager made me stay up top because Pompey were about to take a pen. I could see his point. Had I been in goal I wouldn’t have been able to work up front for the equaliser.

When I was a lad, I thought I’d be able to play football forever. These days, I know it’s not going to last, but the funny thing is I’m not too worried about the end of my career, the day I have to jack it all in. If I’m ever at a stage where I feel I’m not performing as well as I used to, then I’ll take an honest look at myself. I’ll work out whether I’m still able to make a difference in matches at the highest level. I’m not going to hang around to snatch the odd game here and there in the Premier League. I’ll play abroad somewhere, maybe America. I’d love to have a go at coaching if the opportunity comes up.

The thing is, I want to be remembered for playing well in football’s best teams, like United. I want to burn out brightly on the pitch at Old Trafford, not fade away on the subs’ bench.

*****

Hanging up my footy boots is a way off yet. There’s more stuff to be won. I want more league titles, more Champions Leagues – anything United are playing for, I want to win it. I’m into winning titles for the team because winning personal achievements, while being nice, isn’t the same as winning trophies with my teammates. And whatever I do, I do it to be the best that I can. I’m not good at being an also-ran, as anyone who has played with me will know.

For 10 years, it’s been all or nothing for me in the Premier League.

(#u5df184fc-98ff-5601-afea-67b8522b24ad)

Ten years in the Premier League. All the goals and trophies, injuries and bookings driven by one thought: I hate losing. I hate it with a passion. It’s the worst feeling ever and not even a goal or three in a match can make a defeat seem OK. Unless I’ve walked off the pitch a winner, the goals are pointless. If United lose, I’m not interested in how many I’ve scored.

I’m so bad that I even hate the thought of losing. Thinking about defeat annoys me, it does my head in, it’s not an option for me, but when it does happen, I lose it. I get angry, I see red, I shout at teammates, I throw things and I sulk. I hate the fact that I act this way, but I can’t help it. I was a bad loser as a lad playing games with my brothers and mates, and I’m a bad loser now, playing for United.

It doesn’t matter where I’m playing, or who I’m playing against either, I’m the same every time I put on my footy boots. In a practice match at Carrington before the last game of the 2009/10 season, I remember being hacked down in the area twice. I remember it because it annoys me so much. The ref, one of our fitness coaches, doesn’t give me a decision all game and my team loses by a couple of goals. When the final whistle blows and the rest of the lads walk back to the dressing room to get changed, laughing and joking together, I storm off in a mood, kicking training cones and slamming doors.

It’s the same when I’m competing off the pitch. I often play computer games with the England lads when I’m away on international duty. One time I lose a game of FIFA and throw a control pad across the room afterwards because I’m so annoyed with myself. Another night I lean forward and turn the machine off in the middle of a game because I know I’m going to lose. Everyone stares at me like I’m a head case.

‘Come on, Wazza, don’t be like that.’

That annoys me even more, so I boot everyone out of the room and sulk on my own.

It’s not just my teammates I lose it with. I have barneys with people as far away as Thailand and Japan when I play them at a football game online. They beat me; I argue with them on the headset that links the players through an internet connection. I’m a grown man. Maybe I should relax a bit more, but I find it hard to cool down when things aren’t going my way, and besides, everyone’s like that in my family. We’re dead competitive. Board games, tennis in the street, whatever it was that we played when I was a lad, we played to win. And none of us liked losing.

I sometimes think it’s a good thing – I don’t reckon I’d be the same as a footballer if I was happy to settle for second best. I need this desire to push me on when I’m playing, like Eric Cantona and Roy Keane did when they were at United. They had proper passion. I do too, it gives me an edge, it pushes me on to try harder. Those two couldn’t stand to lose. They didn’t exactly make many pals on the pitch either, but they won a lot of trophies. I’m the same. I doubt many players would say they’ve enjoyed competing with me in the past and I like to think that I’m a pain in the backside for everyone I play against. I’m probably a pain in the backside for people I play with as well, because when United lose or look like losing a game at half-time, I go mad in the dressing room.

I scream and shout.

I boot a ball across the room.

I throw my boots down.

I lose it with teammates.

I yell at people and they yell at me.

I’m not shouting and screaming and kicking footballs across the room because I don’t like someone. I’m doing it because I respect them and I want them to play better.

I can’t stand us being beaten.

I yell at players, they yell at me. I don’t take it personally when I’m getting a rollicking and I don’t expect people to take it personally when I dish it out to them. It’s all part of the game. Yeah, it feels like a curse sometimes, the anger and moodiness when I lose, but it’s an energy. It makes me the player that I am.

*****

My hatred of losing, of being second best, starts in Croxteth. My family are proud; Crocky is a proud place and nobody wants to let themselves down or their family down in the street where I live. My family haven’t got a lot, but we have enough to get through and my brothers and I aren’t allowed to take anything for granted as we’re growing up. We know that if we want something, we have to graft for it and I’m told that rewards shouldn’t come easily. I pick that up from my mum, my dad, my nan and my granddad. I learn that if I work hard, I’ll earn rewards. If I try at school, I’ll get the latest Everton shirt – the team my whole family supports – or a new footy if I need one. It’s where the will to work comes from.

This discipline, the desire to win and push myself, also happens away from school. I box at the Crocky Sports Centre with my Uncle Richie, a big bloke with a flat boxer’s nose. He hits pretty hard. I never actually scrap properly but I spar three times a week and the training gives me strength and an even harder competitive streak. Most of all it brings out my self belief.

I think we’re all confident in the family, but I don’t think it’s just the Rooneys. I reckon it’s a Liverpool thing. Everyone’s really outgoing in Crocky; everyone speaks their mind, which I like. As a kid, I learn to take that self-belief into the boxing gym. If ever I get into the ring with a lad twice my size I never think, Look at the size of him! I’m going to get battered. Doing that means I’m beat in my head already. Instead, I go into every fight thinking, I’m going to win, even against the bigger lads. One pal at the gym is called John Donnelly

(#ulink_ca5b01ad-aeb3-555a-ad9f-45cc6ec6f649), he’s older and heavier than me, but every time we spar together, Uncle Richie tells me to take it easy on him. He’s frightened John can’t handle me.

The desire to win and the self-belief on the footy pitch is there from the start too, even when I play for De La Salle, my school team. If ever a player knocks me off the ball in a tackle I work on my strength training in the gym the following week. I promise myself that it won’t happen again. No-one’s going to beat me in a scrap for the ball.

If I look like losing my hunger, Dad pushes me a bit. When I play football on a Sunday afternoon, he always comes to watch. He encourages me to get stuck in. He gets more wound up than me sometimes. He tells me to work harder, to try more. I play one match and it’s freezing, my hands are burning and my feet are like blocks of ice. I run over to the touchline.

‘Here, Dad, I’m going to have to come off. It’s too cold. I can’t feel my feet.’

His face turns a funny colour and he looks like he’s going to blow up with anger.

‘What? You’re cold?’

He can’t believe it.

‘Get out there and run more. Get on with it.’

I leg it around a bit harder to warm myself up. I’m only nine but I know that if Dad’s advice is anything to go by, I’ll have to toughen up even more if I want to be a proper footballer.

*****

All my heroes are battlers.

On the telly, I love watching boxers, especially Mike Tyson because his speed and aggression makes him so exciting. He always goes for the KO. When I watch Everton with Dad, my favourite player is Duncan Ferguson because he’s a fighter like Iron Mike, hard as nails, and I love the way he never gives up, especially if things aren’t going his way. He always gets stuck in. He also scores cracking goals. I could watch him play all day.

I love Everton, I’m mad for them. I write to the club and ask to become the mascot for a game when I’m 10 years old. A few weeks later a letter comes through the door telling me I’ve been chosen and I’m dead chuffed because I’m going to be walking out with the team for the Merseyside derby at Anfield. I step onto the pitch with our skipper, Dave Watson, and Liverpool’s John Barnes and I can’t believe the noise of the crowd. Later I go into the penalty area to take shots at our keeper, Neville Southall. I’m only supposed to be passing the ball back to him gently, but I get bored and chip one over his head and into the back of the net. I can see that he’s not happy, so when he rolls the ball back to me, I chip him again.

I just want to score goals.

A couple of years later, I get to be a ball boy at Goodison Park. Neville’s in goal again and as I run to get a shot that has gone out of play he starts shouting at me. ‘Effin’ hurry up, ball boy!’ he yells. It scares the crap out of me. Afterwards, I go on about it for ages to my mates at school.

That afternoon at Anfield, Gary Speed scores for us, which I’m dead chuffed about because he’s one of my favourite players. I can see that he works hard and he’s a model pro. Someone tells me that he grew up as an Evertonian as well, so when my mum buys me a pet rabbit a little while later, I decide to name him ‘Speedo’. Two days afterwards, the real Speedo signs for Newcastle and I’m moody for days.

*****

The training and the toughening up pays off.

I get spotted by club scouts when I’m nine years old and join Everton, which is like a dream come true. Then I play in the older teams at the club rather than my own age group because I’m technically better and physically stronger than the lads in my year. It’s mad; I don’t let on to the kids my age when I go to footy practice because I never play with them, I don’t really know them. When I’m 14 years old, I work with the Everton Under-19s. Me, a kid, playing against (nearly) grown blokes and competing, scoring goals, winning tackles. It feels great.