скачать книгу бесплатно

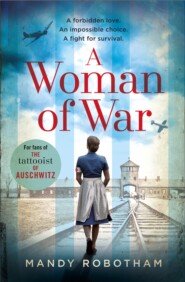

A Woman of War: A new voice in historical fiction for 2018, for fans of The Tattooist of Auschwitz

Mandy Robotham

For readers of The Tattooist of Auschwitz and Kate Furnivall comes a gritty tale of courage, betrayal and love in the most unlikely of places.Germany, 1944. Taken from the camps to serve the Fuhrer himself, Anke Hoff has been assigned as midwife to one of Hitler’s inner circle. If she refuses, her family will die.Torn between her duty as a caregiver and her hatred for the regime she’s now a part of, Anke is quickly swept into a life unlike anything she’s ever known – and she discovers that many of those at the Berghof are just as trapped as she is. Soon, she’s falling for a man who will make her world more complicated still.Before long, the couple is faced with an impossible choice – for which the consequences could be deadly. Can their forbidden love survive the horrors of war – and, more importantly, will they?

A Woman of War

Mandy Robotham

Published by AVON

A Division of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2018

Copyright © Mandy Robotham 2018

Cover design © Becky Glibbery 2018

Cover photographs © Shutterstock

Cover photograph: Woman © Laura Kate Bradley, Arcangel

Mandy Robotham asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008324247

Ebook Edition © December 2018 ISBN: 9780008324230

Version: 2018-11-29

To the boys: Simon, Harry & Finn

And to mothers and midwives everywhere

Table of Contents

Cover (#u27c25b23-bcb6-597c-88e6-dddcc01f26c3)

Title Page (#ub05d293f-5acc-503f-9bf8-f0353ac16423)

Copyright (#uff4a7f61-ac03-54a8-85b1-53f06bd19cbb)

Dedication (#u06834292-ce0f-5879-a9b3-747b609b290f)

Author’s Note (#u7e441d40-7080-5a62-a168-5e7b0a5b341b)

Chapter 1: Irena (#uac69e1d0-4b7f-597f-960a-82323f54096c)

Chapter 2: Exit (#uef33a0a1-b4ea-551f-8b32-4b7b8275bf5a)

Chapter 3: The Outside (#u5b549d50-e87b-515d-8fde-b0b2936dd07c)

Chapter 4: Climbing (#ufb02046a-d397-5f5f-ace8-7264b2031d09)

Chapter 5: New Beginning (#uf9e0863b-d32d-57ff-8162-63d9c492df2d)

Chapter 6: Adjustment (#u9f638652-d356-5faa-91ce-b5040ef1f5f4)

Chapter 7: Eva (#ub4b49bd6-d3c5-5650-acd1-454d24b84520)

Chapter 8: A New Confinement (#ueff837bc-b749-5b12-aada-7c67d9b1838d)

Chapter 9: Contact (#ufc797653-77f7-5032-b8fb-5f841f54dc1d)

Chapter 10: Visitors (#uec4847d4-cfdd-5719-84ab-e3af4d63bf35)

Chapter 11: The First Lady (#uff476341-764a-57e9-afcd-23da1ee25d6e)

Chapter 12: Employment (#uc426d5ca-d8e0-509b-8400-bf35d4bfc4e5)

Chapter 13: Life and Death (#u2f1f6101-df89-5468-be90-fbd5ff616880)

Chapter 14: Renewed Ascent (#u2d6782d4-377b-54d2-bd81-1a14d65e06fd)

Chapter 15: Waiting (#udc43c240-349c-5007-8215-f87ca428cf04)

Chapter 16: Plans (#u579c09e0-faa1-5040-9658-f11222b31d4d)

Chapter 17: A Slice of Life (#ueb1f6498-355d-547d-bd7a-e23a6fce46d0)

Chapter 18: Calming the Fire (#u7e6ec5b8-b48f-56c9-80d3-cd4109ebebe3)

Chapter 19: Watchful Waiting (#u0335e45e-2d73-5c5c-96b5-1365d70acce0)

Chapter 20: Eva’s Strength (#u1d89c3f7-fe7c-56ac-9056-617fbb1036d9)

Chapter 21: Recovery and Reflection (#u78c795b2-c10b-5d24-8bc8-d04e1faee0d1)

Chapter 22: New Demons (#u4933a988-ad1a-5a07-817b-6a3d619088b0)

Chapter 23: Nurturing (#ufd804420-f485-5b45-9f04-7a10c233d5f7)

Chapter 24: A Growing Interest (#ub3e353f9-b914-51ff-9cb1-c88ab2d06cd6)

Chapter 25: New Arrivals (#u7cf83659-8780-53c2-8f99-c99ff738ce09)

Chapter 26: The Good Doctor (#ue1af78e8-8c13-5369-a12a-f2f355720561)

Chapter 27: The Sewing Room (#ueed6edc1-2bb9-5137-9959-dfd4cb34c24b)

Chapter 28: Release (#u920e4bb4-60da-5217-b408-c8b73cf369c5)

Chapter 29: Friends (#u77069db3-7850-5317-8577-cac4c35e85a8)

Chapter 30: Clouds in Springtime (#u17b932a7-6c44-5d01-b8d9-d32feb59d83d)

Chapter 31: Relief (#u2f91c6d1-1da9-57f5-9c11-8fc2256f7764)

Chapter 32: Waiting (#ue21e9c54-7d55-51c8-83bb-ef987783027e)

Chapter 33: Empty Space (#ue640948c-3624-5857-aa31-fdc2c8b10a2a)

Chapter Hidden Listed (#u817ba019-5e48-586a-95a4-db81f2aa0f88)

Chapter 34: Beginnings (#u352a5b28-d6fe-50c5-a9a1-4d47264dcd9d)

Chapter Hidden Listed (#u83ffb793-50d1-5524-b80e-637d505648fc)

Chapter 35: Brewing (#u42da4319-a038-59af-ad2e-ddce457e7a0e)

Chapter 36: A Night Shift (#u367a79ee-4f1e-5abb-b59e-b3a9e6a89bbc)

Chapter Hidden Listed (#u184ffb7d-9110-5af1-ac80-c8b611ccbc1d)

Chapter 37: Watching and Waiting (#u53fa24bc-6297-5079-b10b-c6908d00e70b)

Chapter 38: Imminence (#u19881b51-9334-5035-b81b-0e48cf0a1bd2)

Chapter Hidden Listed (#ue62027b7-ae82-5d13-9477-fcb8e7c2a911)

Chapter 39: Strength of the Web (#ube71a6ff-a998-5f3c-ab1c-c28116ff0cf4)

Chapter 40: A Real World on Top of the Mountain (#uc1776216-40da-50e5-a8fb-c87d739ba161)

Chapter 41: Retribution (#u7473d386-64df-5d4c-ac79-69dce329bbcd)

Epilogue: Berlin 1990 (#uebf796dd-2a00-53a0-95dc-6bdfad35db16)

Acknowledgements (#u1a4a344f-0b46-5f58-8fa3-2412347d4e0c)

About the Author (#u8247e794-673e-5a30-b6fb-1057bd03058d)

About the Publisher (#u55c81021-60b8-5b4e-9045-5ab0a46c073c)

Author’s Note (#ud47a4b05-df93-580e-9ff2-95805e5a7a8b)

Midwives love to talk, analyse and dissect; the post-birth babble in the coffee room is where we relate the beauty of a birth and the small dilemmas: How to relay to women the intensity of what they may go through in labour? Is it fair to describe in detail the two-headed agony and ecstasy of birth before the day? It led me to wonder at the bigger moral issues we might face, a point where we as midwives may not want to give body and soul towards the safety of mother and baby. And who and or where would that be?

For me there was only one answer: a child whose very genetics would cause ripples among those who had suffered hugely at the hands of its father: Adolf Hitler. Combining a fascination for wartime history and my passion for birth, the idea was conceived. Using real characters like Hitler and Eva Braun – both of whom continue to incite strong emotions almost eight decades on – tested my own moral compass. And yet, I retain the premise that all women, at the point of birth, are equal: princess or pauper, angel or devil, in normal labour we all have to dig deep into ourselves. Birth sweeps away all prejudice. Eva, in the moments of labour, is one of those women. So too, the baby is born free of moral stain – an innocent, entirely pure.

While using factual research material and scenarios, this is my take on a snapshot in history. There has been past speculation that the Führer and his eventual bride had a child, but A Woman of War is a work of fiction, my mind asking: What if? Anke too, is a fiction, yet an embodiment of what I sense in many midwives – a huge heart, but with doubts and fears. In other words, a normal person.

1 (#ud47a4b05-df93-580e-9ff2-95805e5a7a8b)

Irena (#ud47a4b05-df93-580e-9ff2-95805e5a7a8b)

Germany, January 1944

For a few moments, the hut was as quiet as it ever could be in the early hours, a near silence broken only by the sound of a few feminine snores. The night monitor padded up and down the lines of bunks with her stick, on the lookout for rats preying on the women’s still limbs, ready to swipe at the voracious predators. Small clouds of human breath rose from the top bunks as it met with the icy, still air – strange not to hear the women coughing in turn, a symphony of ribs racked by the force of infection on their piteous lungs, as if just one more hack would crack their chests wide open. Every thirty seconds, the darkness was split by pinpricks of white as the searchlight did its endless sweep through the holes in the flimsy planks, in the only place we could call home.

I was dozing at the front of the hut, knowing Irena was in the early stages. A sudden cry from her bunk next to the stove broke the silence, as a fierce contraction coiled within her and split her uneasy sleep, spilling through her broken teeth.

‘Anke, Anke,’ she cried. ‘No, no, no … Make it stop.’

Her distress wasn’t of weakness – Irena had done this twice before in peacetime – but of the inevitable result of this process, of labour. A birth. Her baby would be born, and that to Irena was her worst nightmare. While her baby lay inside, occasionally kicking and showing signs it had not sucked away its mother’s life juices and still found wanting, there was hope. On the outside, hope diminished rapidly.

I was soon at her side, gathering the rags and paper we had been harbouring, a bucket of water drawn painstakingly from the well before curfew. She was agitated, in a type of delirium usually seen in the typhus cases. The name of her husband – probably long since dead in another camp – burbled through her dry lips time and again as she thrashed on the thin hay mattress, causing the wooden slats below to creak.

‘Irena, Irena,’ I whispered her name repeatedly, bobbing to catch her gaze while her eyes opened and closed. Unlike women in the Berlin hospitals, mothers in the camp often became otherworldly in labour, taking themselves to another place, a palace of the mind. I imagined it was a way of avoiding the reality that they were bringing their babies into this stark world of horror, creating a perfect nest in their dreams where life failed to provide it.

Much like third labours generally, this one progressed quickly. After simmering for several hours, contractions came one after another, spiralling rapidly. Rosa was soon by my side, roused from her half sleep too. She stoked the pitiful fire and put some of the water on to boil, while another woman brought an oil lamp, the fuel saved for such occasions. That was as much as we had, other than faith in Mother Nature.

The contractions were fierce and the waters broke during one particularly strong moment – a pathetic, meagre amount – but Irena was resisting. In any other scenario, the body would have been forced to bear down, the natural expulsion overwhelming and unrelenting. Women in their first pregnancies often worried whether they would know when it was time to push, and we as midwives could only reassure them – you will know, a power from within like no other, a tidal wave to ride instead of fight. Irena, however, was hanging on to her baby for dear life, a thin snake of mucousy blood just visible now as I looked under her covering. It signalled the body was eager, more than ready to let go. Only a mother’s iron will was clamping the gates shut.

Eventually, after several strong contractions, Irena’s womb won out; a telltale primal grunt, and with the help of the lamplight I saw the baby was on its way, his or her head not yet visible but a distinctive shape behind the thin, almost translucent skin of Irena’s buttocks, rounding out her anatomy. She swished her head in distress, panting and muttering: ‘No, not yet, baby, stay safe,’ fluttering her hands towards her opening in a desperate attempt to will the baby back in. Rosa was at Irena’s head, whispering reassurance, giving her sips of the cleanest water we could find, and I stayed with the lamp below.

Oblivious to its future, this baby was determined to be born. In the next contraction, black hair sprouted through the strained lips of Irena’s labia, and I urged her to ‘Blow, blow, blow,’ hoping to slow her down and avoid any skin tears that we had no equipment or means to stitch, another open wound the rats and lice would target.

Sensing the inevitable, Irena gave in, and her baby’s head slid past the confines of its mother, corkscrewing its way into the world. For a moment or so, as with so many births I’d seen, time stood still. The baby’s head lay on the cleanest rag we had, shoulders and body still inside Irena. Her sweat-stained head fell back on Rosa, a body convulsed with sobs of relief and sadness, and only a sliver of joy. The hut was silent – most of the women had woken, two or three visible heads to a bunk, as curiosity triumphed over the desire for sleep. Still, they only glimpsed, respecting what little privacy she had.

The baby had emerged back to back, looking up at me squarely, and I could see eyes opening and shutting like a china doll’s, mouth forming into a fish-like pout, as if he or she were breathing. The seconds ticked by, but there was no worry, the baby’s lifeline umbilicus giving filtered oxygen from Irena, far purer than the stagnant air around us.

‘It’s fine, all is well, your baby will be here soon,’ I whispered. But nothing, I knew, would make Irena feel anything other than impending fear or sadness.

The contraction brewed, and she shifted her buttocks to make room as the baby’s head made a half turn to one side, allowing the breadth of the shoulders to come through, and Irena’s son slipped out, bathed in only a little more water, mixed with blood. He was a sorry scrap of a thing, a head too large for his tiny, scantily covered limbs and bulbous testicles. Irena had grown him the best she could on her meagre diet of almost no protein or fat, and this was the result. I took the next best rag and wiped off the fluid, stimulating his flaccid body that gave out no sound, and a small part of me thought: ‘Just slip away now, child, save yourself the pain.’ But I carried on chafing at his delicate skin, rubbing some zest into him, as part of our human instinct to preserve life.

Immediately, Irena was back in this world, panicked. ‘Is it all right? Why doesn’t it cry?’