Полная версия:

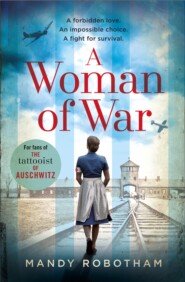

A Woman of War: A new voice in historical fiction for 2018, for fans of The Tattooist of Auschwitz

A Woman of War

Mandy Robotham

Published by AVON

A Division of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2018

Copyright © Mandy Robotham 2018

Cover design © Becky Glibbery 2018

Cover photographs © Shutterstock

Cover photograph: Woman © Laura Kate Bradley, Arcangel

Mandy Robotham asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008324247

Ebook Edition © December 2018 ISBN: 9780008324230

Version: 2018-11-29

To the boys: Simon, Harry & Finn

And to mothers and midwives everywhere

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Author’s Note

Chapter 1: Irena

Chapter 2: Exit

Chapter 3: The Outside

Chapter 4: Climbing

Chapter 5: New Beginning

Chapter 6: Adjustment

Chapter 7: Eva

Chapter 8: A New Confinement

Chapter 9: Contact

Chapter 10: Visitors

Chapter 11: The First Lady

Chapter 12: Employment

Chapter 13: Life and Death

Chapter 14: Renewed Ascent

Chapter 15: Waiting

Chapter 16: Plans

Chapter 17: A Slice of Life

Chapter 18: Calming the Fire

Chapter 19: Watchful Waiting

Chapter 20: Eva’s Strength

Chapter 21: Recovery and Reflection

Chapter 22: New Demons

Chapter 23: Nurturing

Chapter 24: A Growing Interest

Chapter 25: New Arrivals

Chapter 26: The Good Doctor

Chapter 27: The Sewing Room

Chapter 28: Release

Chapter 29: Friends

Chapter 30: Clouds in Springtime

Chapter 31: Relief

Chapter 32: Waiting

Chapter 33: Empty Space

Chapter Hidden Listed

Chapter 34: Beginnings

Chapter Hidden Listed

Chapter 35: Brewing

Chapter 36: A Night Shift

Chapter Hidden Listed

Chapter 37: Watching and Waiting

Chapter 38: Imminence

Chapter Hidden Listed

Chapter 39: Strength of the Web

Chapter 40: A Real World on Top of the Mountain

Chapter 41: Retribution

Epilogue: Berlin 1990

Acknowledgements

About the Author

About the Publisher

Author’s Note

Midwives love to talk, analyse and dissect; the post-birth babble in the coffee room is where we relate the beauty of a birth and the small dilemmas: How to relay to women the intensity of what they may go through in labour? Is it fair to describe in detail the two-headed agony and ecstasy of birth before the day? It led me to wonder at the bigger moral issues we might face, a point where we as midwives may not want to give body and soul towards the safety of mother and baby. And who and or where would that be?

For me there was only one answer: a child whose very genetics would cause ripples among those who had suffered hugely at the hands of its father: Adolf Hitler. Combining a fascination for wartime history and my passion for birth, the idea was conceived. Using real characters like Hitler and Eva Braun – both of whom continue to incite strong emotions almost eight decades on – tested my own moral compass. And yet, I retain the premise that all women, at the point of birth, are equal: princess or pauper, angel or devil, in normal labour we all have to dig deep into ourselves. Birth sweeps away all prejudice. Eva, in the moments of labour, is one of those women. So too, the baby is born free of moral stain – an innocent, entirely pure.

While using factual research material and scenarios, this is my take on a snapshot in history. There has been past speculation that the Führer and his eventual bride had a child, but A Woman of War is a work of fiction, my mind asking: What if? Anke too, is a fiction, yet an embodiment of what I sense in many midwives – a huge heart, but with doubts and fears. In other words, a normal person.

1

Irena

Germany, January 1944

For a few moments, the hut was as quiet as it ever could be in the early hours, a near silence broken only by the sound of a few feminine snores. The night monitor padded up and down the lines of bunks with her stick, on the lookout for rats preying on the women’s still limbs, ready to swipe at the voracious predators. Small clouds of human breath rose from the top bunks as it met with the icy, still air – strange not to hear the women coughing in turn, a symphony of ribs racked by the force of infection on their piteous lungs, as if just one more hack would crack their chests wide open. Every thirty seconds, the darkness was split by pinpricks of white as the searchlight did its endless sweep through the holes in the flimsy planks, in the only place we could call home.

I was dozing at the front of the hut, knowing Irena was in the early stages. A sudden cry from her bunk next to the stove broke the silence, as a fierce contraction coiled within her and split her uneasy sleep, spilling through her broken teeth.

‘Anke, Anke,’ she cried. ‘No, no, no … Make it stop.’

Her distress wasn’t of weakness – Irena had done this twice before in peacetime – but of the inevitable result of this process, of labour. A birth. Her baby would be born, and that to Irena was her worst nightmare. While her baby lay inside, occasionally kicking and showing signs it had not sucked away its mother’s life juices and still found wanting, there was hope. On the outside, hope diminished rapidly.

I was soon at her side, gathering the rags and paper we had been harbouring, a bucket of water drawn painstakingly from the well before curfew. She was agitated, in a type of delirium usually seen in the typhus cases. The name of her husband – probably long since dead in another camp – burbled through her dry lips time and again as she thrashed on the thin hay mattress, causing the wooden slats below to creak.

‘Irena, Irena,’ I whispered her name repeatedly, bobbing to catch her gaze while her eyes opened and closed. Unlike women in the Berlin hospitals, mothers in the camp often became otherworldly in labour, taking themselves to another place, a palace of the mind. I imagined it was a way of avoiding the reality that they were bringing their babies into this stark world of horror, creating a perfect nest in their dreams where life failed to provide it.

Much like third labours generally, this one progressed quickly. After simmering for several hours, contractions came one after another, spiralling rapidly. Rosa was soon by my side, roused from her half sleep too. She stoked the pitiful fire and put some of the water on to boil, while another woman brought an oil lamp, the fuel saved for such occasions. That was as much as we had, other than faith in Mother Nature.

The contractions were fierce and the waters broke during one particularly strong moment – a pathetic, meagre amount – but Irena was resisting. In any other scenario, the body would have been forced to bear down, the natural expulsion overwhelming and unrelenting. Women in their first pregnancies often worried whether they would know when it was time to push, and we as midwives could only reassure them – you will know, a power from within like no other, a tidal wave to ride instead of fight. Irena, however, was hanging on to her baby for dear life, a thin snake of mucousy blood just visible now as I looked under her covering. It signalled the body was eager, more than ready to let go. Only a mother’s iron will was clamping the gates shut.

Eventually, after several strong contractions, Irena’s womb won out; a telltale primal grunt, and with the help of the lamplight I saw the baby was on its way, his or her head not yet visible but a distinctive shape behind the thin, almost translucent skin of Irena’s buttocks, rounding out her anatomy. She swished her head in distress, panting and muttering: ‘No, not yet, baby, stay safe,’ fluttering her hands towards her opening in a desperate attempt to will the baby back in. Rosa was at Irena’s head, whispering reassurance, giving her sips of the cleanest water we could find, and I stayed with the lamp below.

Oblivious to its future, this baby was determined to be born. In the next contraction, black hair sprouted through the strained lips of Irena’s labia, and I urged her to ‘Blow, blow, blow,’ hoping to slow her down and avoid any skin tears that we had no equipment or means to stitch, another open wound the rats and lice would target.

Sensing the inevitable, Irena gave in, and her baby’s head slid past the confines of its mother, corkscrewing its way into the world. For a moment or so, as with so many births I’d seen, time stood still. The baby’s head lay on the cleanest rag we had, shoulders and body still inside Irena. Her sweat-stained head fell back on Rosa, a body convulsed with sobs of relief and sadness, and only a sliver of joy. The hut was silent – most of the women had woken, two or three visible heads to a bunk, as curiosity triumphed over the desire for sleep. Still, they only glimpsed, respecting what little privacy she had.

The baby had emerged back to back, looking up at me squarely, and I could see eyes opening and shutting like a china doll’s, mouth forming into a fish-like pout, as if he or she were breathing. The seconds ticked by, but there was no worry, the baby’s lifeline umbilicus giving filtered oxygen from Irena, far purer than the stagnant air around us.

‘It’s fine, all is well, your baby will be here soon,’ I whispered. But nothing, I knew, would make Irena feel anything other than impending fear or sadness.

The contraction brewed, and she shifted her buttocks to make room as the baby’s head made a half turn to one side, allowing the breadth of the shoulders to come through, and Irena’s son slipped out, bathed in only a little more water, mixed with blood. He was a sorry scrap of a thing, a head too large for his tiny, scantily covered limbs and bulbous testicles. Irena had grown him the best she could on her meagre diet of almost no protein or fat, and this was the result. I took the next best rag and wiped off the fluid, stimulating his flaccid body that gave out no sound, and a small part of me thought: ‘Just slip away now, child, save yourself the pain.’ But I carried on chafing at his delicate skin, rubbing some zest into him, as part of our human instinct to preserve life.

Immediately, Irena was back in this world, panicked. ‘Is it all right? Why doesn’t it cry?’

‘He’s just a little shocked, Irena, give him time,’ I said, feeling my own adrenalin peak then as I chanted in my own head: ‘Come on, baby, breathe for her, come on,’ while talking and blowing on his startled features: ‘Hey, little one, come on now, give us a cry.’

After one more vigorous rub, he coughed, gasped, and seemed almost to take in his surroundings with even wider eyes. Instantly, I passed him up to Irena, and settled him next to her skin. The effort of labour had made her the warmest surface in the room and he began murmuring at her, rather than a lusty cry. Still, any sound was breathing; it was life.

For the first time in months, Irena’s features took on a look of complete satisfaction. ‘Hey, my lovely,’ she cooed, ‘what a handsome boy you are. How clever you are.’ After two girls he was her first boy, her husband’s desire. What everyone was thinking, but no one voiced, was that she was unlikely to see any of them grow into their potential, into people. Not a soul would burst her temporary bubble.

Without a word, Rosa and I went into our defined roles. She stayed with Irena and the baby, tucking him further under any covers we had, while I kept a vigilant eye on Irena’s opening as blood pooled onto the rag. It was normal – for now. But since I began my training, placentas had made me twitch far more than babies ever had. Sheer exhaustion could make the body shut down and simply refuse to expel the placenta. Beads of sweat began forming on my brow and at the nape of my neck. To lose a woman and baby at this stage would seem like Mother Nature really had no soul.

Yet she came through, as she had again and again, a constant in this ugly, shifting humanity. Irena’s features, still awash with hormones of sheer love, crumpled with pain, as another contraction took hold. In another two pushes, the placenta flopped onto the rags, tiny and pale. The baby had stripped every ounce of fat from this pregnancy engine and it was a wrung-out rag with its stringy cord attached. Well-nourished German women produced fat, juicy cords that coiled like helter-skelters into blood-red tissue, fed well in their nine months. I hadn’t seen anything other than meagre ones since coming into the camp.

Once I had checked to ensure the placenta had all come away – anything left inside could cause a fatal infection – we opened the door to the hut and threw it outside, away from the entrance. There was a fierce scrabbling as several of the rats, some nearing the size of cats, fought to be the first through their entry holes in the side of the hut, to the lion’s share of fresh meat. Months before, there had been cross words among the women about feeding the rats in this way, since they could only get bigger, but these creatures were relentless in their quest for food. If they had none, they turned towards us, nibbling at the skin of women too sick to move, too lifeless to realise. If the creatures were distracted, or satiated, at least we had some respite from their prowling. I hated the vermin, but at the same time, I could admire their survival instinct. Vermin or human, we were all simply trying to live.

Rosa and I cleaned around Irena with whatever we could find, she enjoying skin-to-skin time with her baby – we had no clothes to dress him in anyway. He fed hungrily at her papery breast, his little cheeks sucking for dear life on almost dry flesh. The hormone release caused more cramping in her tired belly, but you could tell she almost enjoyed the draw on her body. Rosa brewed some nettle tea from the leaves we had saved, and Irena’s face was pure joy for an hour or so. But as the dark diminished and daylight began licking through the cracks in the walls, the atmosphere in the hut became edgy. Time for Irena and her baby was limited.

Some of the women moved towards her, a low hum gathering as they encircled her bed, forming into a welcome song for the baby. In the real world, they would have brought gifts, food or flowers. Here, they had nothing to give, except the love squirrelled away in a protected corner of their hearts, some hope they occasionally let flutter; so many had already lost children, been parted, ached in every way possible for the smell of their babies’ wet heads, siblings, nieces, nephews. They were all part of the longing. One woman offered up a blessing, in the absence of a rabbi, and they accepted the baby as one of their own. His mother named him Jonas, after her husband, and smiled as he became part of history, recognised.

Rosa and I sat in the corner, me as the only non-Jew in the hut, taking stock of the beautiful sound. I had one ear out for the camp waking up, the guards shouting their orders, the constant clumping of their boots on the hard, frosted ground outside. It was only a matter of time before they entered our domain. Hiding the child was pointless. We had tried as much once before – a newborn’s constant, mewling hunger cries were impossible to muffle. That time, it had resulted in the loss of both mother and baby in the coldest, cruellest way possible. If we could save at least one, it counted as something. Irena had children she may well find again. Unlikely, but always possible.

In the end, Irena managed almost three hours of precious contact with her newborn. At seven, the door was thrown open, a fierce wind whipping as the guards came in to make their roll call. This hut had been excused an outside count only because so many of the women were bed-bound and the guards grew dangerously irritated if they fell during the long wait. I had appealed to the camp Commandant for an inside count and been successful – a surprising and rare concession on their part.

It was the first guard who sensed the new arrival. I was almost sure this particular one had worked in hospitals before the war, possibly as a midwife; she looked at me with deep suspicion, a grimy furrow to her large brow, particularly when I was with the Jewish women, as if she could not contemplate even touching them. She had no qualms, however, about employing the butt of her cosh, a target she perfected in the base of their wizened skeletons to cause maximum pain. She also had a second, more sinister, speciality.

It was her nose that caught the coppery taint of birth blood, and not that of the second, shadowy guard.

‘You’ve had another one, then?’

I walked forward, as I always did. The exchange had become a game I was almost certain to lose, but it never stopped me trying.

‘The baby’s only been born an hour,’ I lied. ‘It’s not long. Just a little more time. It won’t interfere with the count.’

She scanned up and down the hut, the sixty or so sets of eyes upon her, Irena’s normally dull gaze the whitest I had ever seen. For a second, the guard looked as if she was considering a minor reprieve. Then, she sniffed and grunted, ‘You know the rules. I don’t make them. It’s time.’ The justification for ninety per cent of the degradation in the camp was the same – it’s not our fault, we’re only following orders. The other ten per cent was pure enjoyment.

It was then Irena burst out of her own birth world, clutching the baby to her bare breast, springing off the bed and backing into the corner near the stove, a trickle of blood following her.

‘No, no please,’ she cried. ‘I can do anything. I will do anything, anything you want.’

The guard’s granite reflection told Irena her bargaining power was worthless, so she turned on herself: ‘Take me instead. Take me now, but leave the baby.’ Irena aimed her frenzied voice at me. ‘Anke? You can care for the baby, can’t you? If I’m gone?’

I nodded a yes, but in reality I couldn’t; the few non-Jews allowed to keep their babies had little enough milk for their own newborns, let alone another one scraping at the breast. The infants succumbed to malnutrition in a matter of weeks, and to glimpse a baby beyond a month was unusual. I wouldn’t even need to ask – not one of these desperate appeals had ever worked. We all held our breath for Irena, a scene we had witnessed too many times, but which never ceased to feel completely surreal. A mother having to beg for her baby’s life.

The female guard sighed, boredom apparent. The next step was inevitable, but every mother, if they weren’t immobile or nearing an unconscious state, made the same unrealistic plea. It was a mother’s reflex: laying down your own life to save a new one.

‘Now come on,’ said the guard, moving towards Irena, ‘don’t make it harder. Don’t make me hurt you.’

She made a grab for the cloth, and Irena backed herself further into the corner. The baby’s sudden howling almost masked the crack to Irena’s body, and the guard emerged from the scuffle with the cloth and tiny limbs loosely wrapped. She turned, eyes narrowing to match the thin line of her lips. The heavy boots clomped as she marched towards the door, while we immediately crowded around Irena, as a protective field; if she ran out in pursuit of the guard she would almost certainly be shot by snipers on the lookout posts. She lunged like the fiercest of grizzly bears out of the shadows, broken teeth bared, a tornado of desperation, and we caught her in our human net. The high, shrill screams would have filled the air outside, and I imagined the camp stopping for a second, knowing the deathly protocol was about to happen.

Instantly, the women started up a song, a lament, the volume rising rapidly, as the group took on a unified swaying, with Irena at its core, a shield around her suffering. It was meant as comfort, but there was another purpose – to mask the sound of the baby hitting the barrel of water, as shocking as gunfire if you’ve ever heard it. Rosa caught my eye, nodded and was through the door in an instant, hoping to scoop up the pitiful body after the guard tossed it aside, in time to stop the rats and the guard dogs staking their claim. A placenta was one thing, but a human body – a person. It was unthinkable.

After several moments, Irena’s shrieking died away, replaced with a low moan seeping from her heart’s core, a consistent braying that was beyond words. I had only ever heard such a sound during summers spent on my uncle’s farm in Bavaria, when the newborn calves were taken away to market. Their bereft mothers kept up a constant, needy calling throughout the day and well into the night, searching blindly for their offspring. I would lie in bed with my hands over my ears, desperate to block out the torturous mooing. As I got older, I always asked Uncle Dieter when it was time to take the calves to market and arranged my visits to avoid them.

I cleared up as best I could, and then busied myself seeing to some of the other sick women in the hut, changing a few meagre dressings, giving them water and just holding them as they coughed uncontrollably. At those times, I thanked the automated nurse training I had been through, where doing menial tasks required little thinking. I didn’t want to give any thought to, or process, what had happened that morning, and many others besides.