скачать книгу бесплатно

Despite the misunderstandings and squabbles that ensued, Andrea and Giustiniana’s relationship deepened through the spring and summer of 1755 to the point that very little else seemed to matter to them anymore. All their energies were devoted to making time for themselves and finding places to meet. They had become experts at escaping the restrictions imposed on them and moved stealthily from alcove to alcove. Their love affair consumed their life, and it gradually transformed them.

Giustiniana had been known as a lively and gregarious young woman. The affectionate nickname inglesina di Sant’Aponal conjured up a refreshing image of youth and grace. Soon after returning to Venice, Giustiniana, being the eldest, had begun to share with her mother the duties of a good hostess while Bettina, Tonnina, Richard, and William were still under the care of Toinon. This role had come naturally to her. She had felt at ease in their drawing room or over at the consul’s, delighting everyone with her charm. But by 1755 she was tired of all that, tired of performing onstage. She hardly recognized herself. “Coquetry was all I really cared for once,” she told Andrea in a moment of introspection. “Now I can barely manage to be polite. Everything bores me. Everything annoys me. People say I have become stupid, silly; that I am hopeless at entertaining guests. I realize they’re right, but I don’t much care.” She spent her days writing letters to Andrea, worrying about whom he was seeing, planning their next meeting—where, at what time, and, always, what to do with the keys. When she did go out with her mother—to lunch at the consul’s, or to church, the theater, the Ridotto—the people she chose to talk to, what she said, how she said it: everything she did, in one way or another, related to Andrea.

The affair had become all-consuming for Andrea as well. “My love, you govern my every action,” he confessed to her. “I do not think, I do not feel, I do not see anything but my Giustiniana. Everything else is meaningless to me…. I simply cannot hide my love for you from others anymore.” He still made the usual rounds—a family errand, a trip to the printer Pasquali on behalf of the consul, a lunch at Ca’ Tiepolo, and in the evening a visit to the theater. But his life outside the secret world he shared with Giustiniana no longer seemed very stimulating or even much fun. After the death of his uncle Andrea the year before, Ca’ Memmo had received fewer visitors and had ceased to be the scintillating intellectual haven of years past. At this time, too, Andrea’s mother, obsessed about Casanova’s influence on her three boys, finally had her way and convinced the inquisitors to have him arrested.

(#ulink_f6e80933-b740-5e52-a0d5-a471d508ad5c) The heated, late-night conversations at the crowded malvasìe on the latest book from Paris or the new play by Goldoni had lost their most entertaining participant.

Andrea’s personal project for establishing a French theater in Venice was going nowhere, and Giustiniana worried that she might be the main cause of his lack of progress: “Are you not working on it because of me? Dear Memmo, please don’t give up. If only you knew how much I care about your affairs when your honor is at stake. Especially this project, which, given its scale, the detailed manner in which you planned it, and the excellence with which you carried out every phase, was meant to establish your reputation. And to think that my feelings for you—true as they are—might have caused you so much damage. I am mortified.” Andrea admitted that he had made little progress and “all the people involved” in the project were furious with him. “They say I have been taking them for a ride all along. The talk of the town is that the theater project has fallen through because of my excessive passion for you. By God, I couldn’t care less. I only wish to tell you that I love you, my heart.” Sweetly, he added that he would now start working on it again “because it will feel I will be doing something for you. [After I received your letter] I dashed off to the lawyers to get them started again. They weren’t in the office, but I shall find them soon enough.” In the end, despite fitful efforts, the project never got off the ground.

Andrea kept up with his mentor Carlo Lodoli, the Franciscan monk who continued to hold sway among the more open-minded members of the Venetian nobility. Now that he was no longer Lodoli’s student, Andrea saw him less often, but he was anxious that Giustiniana should also benefit from the mind that had influenced him so profoundly. He encouraged his old teacher to visit her as much as possible and draw her into his circle of followers. Giustiniana always welcomed these visits, starved as she was of new books and new ideas in the restricted intellectual environment her mother fostered at home. Most of all she delighted in the chance to spend time with a person who knew the man she loved so well. When Lodoli came to visit, it was as if he brought Andrea with him—at least in spirit. “He just left,” Giustiniana reported to her lover. “He kept me company for a long time, and we spoke very freely. I appreciated our conversation today immensely—more than usual. He is the most useful man to society…. But beyond that, he talked a lot about you and he praised you for the virtues men should want to be praised for—the goodness of your soul and the truthfulness of your spirit.”

For several years Consul Smith’s library had been a second home for Andrea. He continued to visit the consul regularly during his secret affair with Giustiniana, helping him catalogue his art and book collections. Nearly two years had gone by since the two lovers first met in that house. As Andrea worked, he luxuriated in tender memories of those earlier days, when they had been falling in love among the beautiful pictures and the rare books. “Everything there [reminds] me of you…. Oh God, Giustiniana, my idol, do you remember our happiness there?”

In reality, Andrea stopped at the consul’s more out of a sense of duty and gratitude than for pleasure. The old man could be demanding. “When he starts talking after his evening tea, he never stops,” Andrea reported with a sense of fatigue. “He generally asks me to stay on even while he has himself undressed.” These man-to-man ramblings often touched on the Wynnes, and on several occasions Andrea could not help but notice with amusement the vaguely lustful tone Smith had begun to use when he talked about Giustiniana.

Inevitably, as Andrea and Giustiniana’s lives became more entwined and inextricable, so the hopelessness of their situation gradually sank in, bringing with it more tension and crises. Andrea filled his letters with declarations of love and devotion, but he never offered much to look forward to—there was no long-term plan that, however vague, might allow Giustiniana to dream about a future together. Instead, he made offhand remarks about how much simpler it would be if she were married to someone else or, better still, if she were a young widow “so that we wouldn’t have to take all these precautions and I could show the world how much I adore you.”

Giustiniana was having a harder time than Andrea. Her letters, always more impulsive and emotional than his, grew wilder as she swung between bliss and despair. Venice could seem such a hostile place—a watery labyrinth of mirrors and shadows and whispers. She could not get a grip on Andrea’s life or, as a consequence, on her own. The more time passed, the more she felt she was losing her way. Again and again she was overcome by waves of jealousy that brought her to breaking point.

Caterina (Cattina) Barbarigo was a great beauty and a notorious femme fatale. She held court in a casino that was much in vogue among progressive patricians and viewed with suspicion by the inquisitors. Though older than Andrea—she was married and the mother of two beautiful daughters—she liked surrounding herself with promising young men. He, in turn, was delighted to be drawn into her circle of friends—even at the cost of hurting Giustiniana’s feelings. “All day you’ve been at Cattina Barbarigo’s, haven’t you?” she asked accusingly. “Enough, I shan’t complain about it. But why have I not seen you? Why have I not received a line from you? Now that I think of it, it is perhaps better not to have received a note from you because you probably would have written late at night, in haste, and maybe only out of a sense of duty. Tomorrow, perhaps, you will write to me with greater ease.” But there was no letter on the following day, or the next, or the one after that. On the fourth day of silence her anxiety turned into rage:

You should be ashamed of yourself, Memmo. Could one possibly behave worse toward a lover one claims to be desperately in love with? I write to you on Saturday, and you don’t answer because you are at Barbarigo’s house. Sunday I never see you even though I spend the entire day at my window. And no letter—even though you know very well that on Mondays I go out and you should want to find out what the plan is in order to see me. Or perhaps you did write to me but your friend could not deliver? Do you suppose I will believe that you could not find another way of getting a letter to me, considering I had been two days without any news about you? … My mother has been ill for many days, and we could have been seeing each other with fewer precautions. But no—Memmo is having fun elsewhere. He does not even think about Giustiniana except when a compelling urge forces him to. What must I think? I hear from all sides about your new games and your oh-so-beloved old friendships.

Naturally, Andrea pleaded complete innocence: “For heaven’s sake, don’t be so mean. What rendezvous are you talking about? What have I done to merit such scorn? My dear sweet one, you must quiet down. Trust me or else you’ll kill me.” He explained, rather obliquely, that tactical considerations and nothing else occasionally forced him to be silent for a few days or to interrupt the flow of letters. But she should never forget that if he sometimes made himself scarce, it was for her sake and certainly not because he was chasing young ladies around: “You know I love you, and for that very reason, instead of complaining about your perpetual diffidence, I only worry about your position. I would have written to you every day to tell you what I was up to, but you know how afraid I am about writing to you—your mother is capable of all sorts of beastliness. All I care about is making sure the members of your household and our enemies and the crowd of people that follow every step we take do not discover our relationship by some act of imprudence on our part.”

Giustiniana was not reassured by Andrea’s words. In fact, his shifty attitude was making her more upset and more defiant:

How could you swear to me that all you cared about was my position, when in fact you were merely trying to get away from me using prudence as a pretext to rush over to see N.

(#ulink_4616de5b-b18e-5387-81c7-d2aa54ff4b2a)? Don’t be so sure of the power you have over me, for I shall break this bond of ours. I have opened my eyes at last. My God! Who is this man to whom I have given my deepest love! Leave me, please leave me alone. I’m just a nuisance to you. Before long you will hate me. You villain! Why did you betray me? … Everyone now speaks of your friendship with N. At first you explained yourself, and so I was at peace again and I even allowed you to be seen with her in public … and after our reconciliation you rushed off to see her again. What greater proof of your infidelity? Damn you! I am so angry I cannot even begin to say all I want…. Don’t even come near me, I don’t want to see you…. Now I see why you told me to pretend that our friendship was over; now I plainly see how fake your sincerity was, your infamous caution…. Now I know you. Did you think you could make fun of me forever? Enough. I cease to be your plaything.

Were the rumors true? Was Andrea pursuing N., or was Giustiniana working herself into a spiral of groundless jealousy? Whatever was going on, Andrea had clearly underestimated the depth of Giustiniana’s desperation. He suddenly found himself on the defensive, struggling to contain her rage: “How can I describe to you the state I am in, you cruel woman? My mind is busy with a thousand thoughts. I’m agitated and worried about a thousand questions. And you, for heaven’s sake, find nothing better to do than to treat me in the most inhuman way. Where does it all come from? What have I done to deserve all this? … Can it be that you still don’t know my heart? … Come here, my sweet Giustiniana, speak freely to your Memmo.”

Andrea understood more plainly now that as long as Giustiniana felt locked into a relationship with no future she would only become more anguished and more intractable and their life would become hell. But he remained ambivalent: “Tell me if you want to get yourself out of this situation you’re in. Tell me the various possibilities, and however much they might be harmful to me, if they will make you happy…. Speak out, and you will see how I love you.” Was he conjuring up the idea of an elopement? Was he beginning to consider a secret marriage, with all the negative consequences it would have entailed? If so, he was going about it in a very circuitous and tentative way, as if this were merely a short-term device to placate Giustiniana’s wrath. In fact, already in his next letter he retreated to his older, more traditional position: their happiness, as far as Andrea was concerned, hinged on finding Giustiniana a husband. “Alas, until you are married and I am able to see you more freely, there won’t be much to gain. Meanwhile let us try to hurt each other as little as possible.”

Giustiniana, however, had not exhausted her rage. Andrea’s letters suddenly seemed so petty and predictable. Where was the strong, willful young man she had fallen so desperately in love with? In the increasingly frequent isolation of her room at Sant’Aponal, she decided to put an end to their love story. Better to make a clean break, as painful as it would be, than to endure the torture Andrea was inflicting upon her.

This is the last time I bother you, Memmo. Your conduct has been such that I now feel free to write you this letter. I do not blame you for your betrayal, your lack of gratitude, the scarcity of your love, your scorn. No, Memmo. I was very hurt by all this, but I’ve decided not to complain or to wallow in vindictive feelings. You know how much I have loved you; you know what a perfect friend I have been to you. God knows that I had staked my entire happiness on our love. You knew it. Yet you allowed me to believe that you loved me with the same intensity…. And now that I know you, that I see how you tricked me, I give you an even greater token of my passion by breaking this tenacious bond. After all your abuse, your disloyalty, I was already on the verge of abandoning you. But your scorn of the last few days, the lack of any effort on your part to explain yourself, your continuous indulgence in the things you know make me unhappy, your complete estrangement have finally made me see that you could not hope for a better development. I have opened my eyes, I have learned to know you and to know me, and I have become adamant in my resolution never to think again about a man capable of such cruelty, such contempt, such utter disloyalty to me.

So everything between us is over. I know I cannot give you a greater pleasure than this…. And I also know that my peace of mind, my well-being, maybe even my life will depend on this break. I shall never hate you (see how much I can promise), but I will feel both pleasure and displeasure in your happiness as well as in your misfortunes. I will say more: I will never again love anyone the way I have loved you, ungrateful Memmo. You will oblige me by handing over all my letters … as they serve no other purpose than to remind me of my weakness and your wickedness. So please give them back so that I may burn them and remove from my sight everything that might remind me of all I have done for such an undeserving man.

Here is your portrait, once my delight and comfort, which I don’t want anywhere near me. Ask the artist

(#ulink_64c275c5-45dd-543f-bfea-2c385688ed46)to bring me the one you had commissioned of me—I will pay for it in installments and keep it. Your vanity has already been sufficiently satisfied as it is. Everyone knows how much I have loved you. Please don’t let me see you for another few days. I know how good our several days’ separation has been for me, and I have reason to believe that I will benefit by extending it. I forgive you everything. I have deserved this treatment because I was foolish enough to believe that you were capable of a sincere and enduring commitment; and I guess you are not really to blame if you can’t get over your own fickleness, which is so much a part of your nature. I ask neither your friendship nor a place in your memory. I want nothing more from you. Since I can no longer be the most passionate lover, I don’t want to be anything else to you. Adieu, Memmo, count me dead. Adieu forever.

Giustiniana’s dramatic break cleared the air. Within days the poisonous atmosphere that had overwhelmed them dissolved and they were in each other’s arms again, filled with love and desire. Giustiniana even laughed at her own foibles:

Oh God, my Memmo, how can I express these overflowing emotions? How can I tell you that … you are my true happiness, my only treasure? Lord, I am crazy. Crazy in the extreme. And what about all that happened to me in the last few days? Do you feel for me? … With my suspicions, my jealousy, my love…. Only you can understand me because you know my heart and the power you have over it…. I don’t know how my mood has changed so quickly, and why I even run the risk of telling you this! No, I really don’t know what’s happening to me…. Anyway, we’ll see each other tomorrow. Meanwhile I think I’ll just go straight to bed. After having been wrapped up in sweet thoughts about my Memmo and so full of him, I couldn’t possibly spend the rest of the evening with the silly company downstairs!

Andrea was so eager to hold Giustiniana in his arms again that even the twenty-four-hour wait now seemed unendurable to him. Alone in his room at Ca’ Memmo he let himself drift into erotic fantasies, which he promptly relayed to his lover:

Oh, my little one, my little one, may I entertain you with my follies? Do you have a heart to listen? I am so full of dreams about you that the slightest thing is enough to put me into a cosmic mood. For example, I read one of your letters … and I focus on a few characters in your handwriting and I begin to stare at them and I tell myself: here my adorable Giustiniana wrote … and sure enough I see your hand, your very own hand, oh Lord, I kiss your letter not finding anything else to kiss, and I press it against me as if it were you, oh, and I hug you in my mind, and it’s really too much; what to do? I cannot resist any longer. Oh my Lord, oh my Lord, now another hand of yours is relieving me, oh, but I can’t go on…. I cannot say more, my love, but you can imagine the rest…. Oh Lord, oh Lord…. I speak no more, I speak no more.

In such moments of playful abandon Andrea felt he was capable of doing “even the most irresponsible thing … yes … I feel this urge to take you away and marry you.” And when he opened up that way, Giustiniana always gave herself completely: “My Memmo, I shall always be yours. You enchant me. You overwhelm me. I will never find another Memmo with all the qualities and all the defects that I love about you. We are made for each other so absolutely. All that needs to happen is for me to become less suspicious and for you to moderate that slight flightiness, and then we’ll be happy.”

After these moments of ecstasy, however, the gloominess of their situation would steal over their hearts once more. Andrea wondered how their relationship could possibly survive. “We will never have a moment of peace and quiet. Meanwhile, you, believing as you do in everything you hear. Good Lord, I don’t know what to do anymore! You will never change as long as I have to be away from you. I see that it is impossible for you to believe that I am all yours, as I am, and it is impossible to change your mother, or your situation, so what am I to do?” he asked Giustiniana with quiet desperation. “I don’t know how to hold on to you.”

(#ulink_9ee72e2a-c905-5db8-956d-3b70db3624d2)It is probable that a combination of factors determined Casanova’s arrest on July 25, 1755—his openly proclaimed atheism, his dabbling with numerology, his reputation as an able swindler of a rather gullible trio of old patricians. Lucia Memmo’s pressure on the inquisitors also played a role. Certainly Casanova was convinced of this. “His [Andrea’s] mother had been a party to the plot that sent me to prison,”

(#litres_trial_promo) he later wrote in his History of My Life. But he never bore a grudge toward the sons.

(#ulink_a9a2d341-ca10-5dc5-88b7-08a88ef5a993)Clearly a different N. from the one who was lending them the casino.

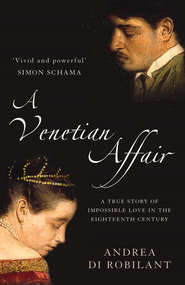

(#ulink_71ec9091-ebc2-581f-bcfb-67e3fe886fc1)Andrea had commissioned a portrait from “Nazari,” possibly Bartolomeo Nazzari (1699–1758), a fashionable artist in Venice at the time and a protégé of Consul Smith. Alas, the portrait has never been found.

CHAPTER Three (#ulink_09fa1f13-d29b-5089-b1db-918e28ea71b6)

In early December 1755, news quickly spread that Catherine Tofts, the elusive wife of Consul Smith, had died after a long illness. She had once been an active and resourceful hostess, often giving private recitals in her drawing room. There is a lovely painting by Marco Ricci, one of Smith’s favorite artists, of Catherine singing happily with a chamber orchestra. But the picture was painted shortly after her marriage to Smith and before the death of her son. As the years went by, she was seen less and less (Andrea never mentions her in his letters). Toward the end of her life it was rumored that she had lost her mind and her husband had locked her up in a madhouse.

Smith organized a grand funeral ceremony, which was attended by a large contingent of Venice’s foreign community (the Italians were absent because the Catholic Church forbade the public mourning of Protestants). A Lutheran merchant from Germany, a friend of the consul, recorded the occasion in his diary: “Signor Smith received condolences and offered everyone sweets, coffee, chocolate, Cypriot wine and many other things; to each one he gave a pair of white calfskin gloves in the English manner.” Twenty-five gondolas, each with four torches, formed the procession of mourners. The floating cortege went down the Grand Canal, past the Dogana di Mare, across Saint Mark’s Basin, and out to the Lido, where Catherine’s body was laid to rest in the Protestant cemetery: “The English ships moored at Saint Mark’s saluted the procession with a storm of cannon shots.”

(#litres_trial_promo)

The consul was eighty years old but still remarkably fit and energetic. He had no desire to slow down. By early spring gossips were whispering that his period of mourning was already over and he was eager to find a new wife—a turn of events that caused quite a commotion in the English community.

John Murray, the British Resident, had had a prickly relationship with Smith ever since he had arrived in Venice in 1751. Smith had vied for the position himself, hoping to crown his career by becoming the king’s ambassador in the city where he had spent the better part of his life. But his London connections had not been strong enough to secure it, and Murray, a bon vivant with a keener interest in women and a good table than in the art of diplomacy, had been chosen instead. “He is a scandalous fellow in every sense of the word,” complained Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, who, rather snobbishly, preferred the company of local patricians to that of her less aristocratic compatriots. “He is not to be trusted to change a sequin, despised by this government for his smuggling, which was his original profession, and always surrounded with pimps and brokers, who are his privy councillors.”

(#litres_trial_promo) Casanova, predictably, had a different view of Murray: “A handsome man, full of wit, learned, and a prodigious lover of the fair sex, Bacchus and good eating. I was never unwelcome at his amorous encounters, at which, to tell the truth, he acquitted himself well.”

(#litres_trial_promo)

Smith did not hide his disappointment. In fact he went out of his way to make Murray feel unwelcome, and the new Resident was soon fussing about the consul with Lord Holderness, the secretary of state, himself an old Venice hand and a friend to the Wynnes: “As soon as I got here I tried to follow your advice to be nice to Consul Smith. But he has played so many unpleasant tricks on me that I finally had to confront him openly. He promised me to be nice in the future—then he started again, forcing me to break all relations.”

(#litres_trial_promo)

Catherine’s death and, more important, Smith’s intention to marry again brought a sudden thaw in the relations between the Resident and the consul. Murray conceived the notion that his former enemy would be the perfect husband for his aging sister Elizabeth, whom he had brought over from London (perhaps Murray also calculated that their marriage would eventually bring the consul’s prized art collection into his hands). Smith was actually quite fond of Betty Murray. He enjoyed her frequent visits at Palazzo Balbi. She was kind to him, and on closer inspection he found she was not unattractive. Quite soon he began to think seriously about marrying “that beauteous virgin of forty,” as Lady Montagu called her.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Murray and his sister were not alone in seeing the consul in a new light after Catherine’s death. Mrs. Anna too had her eye on him, because she felt he would be the perfect husband for Giustiniana: Smith could provide her daughter a respectable position in society as well as financial security. Furthermore, he had been a friend of the family for twenty years, and he would surely watch over the rest of the young Wynnes—at least for the short time that was left to him. After all, wasn’t such a solution the best possible way to fulfill the promise he had made to look after Sir Richard’s family? Mrs. Anna began to lure the consul very delicately, asking him over to their house more frequently, showing Giustiniana off, and dropping a hint here and there. She set out to quash the competition from Betty Murray while attempting to preserve the best possible relations with her and her brother. Inevitably, though, tensions in their little group rose, and Betty Murray reciprocated by drawing the consul’s attention to the fact that, as far as she could tell, Giustiniana still seemed very much taken with Andrea.

At first Giustiniana was stunned by her mother’s plan, but she knew that the matter was out of her hands. And although she was only eighteen, she did not express disgust at the idea of marrying an octogenarian. She was fond of Smith, and she also recognized the material advantages of such a marriage. But all she really cared about was how the scheme would affect her relationship with Andrea. Would it protect their love affair, or would it spell the end? Would it be easier for them to see each other or more difficult? The consul was so old that the marriage was bound to be short-lived. What would happen after he died?

Andrea had often said, sometimes laughing and sometimes not, that their life would be so much happier if only Giustiniana were married or, even better, widowed. It had been fanciful talk. Now, quite unexpectedly, they contemplated the very real possibility that Giustiniana might be married soon and widowed not long after. Andrea became quite serious. He set out his argument with care:

I want you to understand that I want such a marriage for love of you. As long as he lives, you will be in the happiest situation…. You will not have sisters-in-law and brothers-in-law and God knows who else with whom to argue. You will have only one man to deal with. He is not easy, but if you approach him the right way from the beginning, he will eagerly become your slave. He will love you and have the highest possible regard for you…. He is full of riches and luxuries. He likes to show off his fortune and his taste. He is vain, so vain, that he will want you to entertain many ladies. This will also open up the possibility for you to see gentlemen and be seen in their company. We will have to behave with great care so that he does not discover our feelings for each other ahead of time.

Andrea began to support Mrs. Anna’s effort by dropping his own hints to Smith about what a sensible match it would be. Giustiniana stepped into line, though warily, for she continued to harbor misgivings. As for the consul, the mere prospect of marrying the lovely girl he had seen blossom in his drawing room put him into a state of excitement he was not always able to contain. Andrea immediately noticed the change in him. “[The other evening] he said to me, ‘Last night I couldn’t sleep. I usually fall asleep as soon as I go to bed. I guess I was all worked up. I couldn’t close my eyes until seven, and at nine I got up, went to Mogliano,

(#litres_trial_promo) ate three slices of bread and some good butter, and now I feel very well.’ And to show me how good he felt he made a couple of jumps that revealed how energetic he really is.”

Word about a possible wedding between the old consul and Giustiniana began to circulate outside the English community and became the subject of gossip in the highest Venetian circles. Smith did little to silence the talk. “He is constantly flattering my mother,” Giustiniana wrote to Andrea. “And he lets rumors about our wedding run rampant.” Andrea told Giustiniana he had just returned from Smith’s, where a most allusive exchange had taken place in front of General Graeme,

(#litres_trial_promo) the feisty new commander in chief of Venice’s run-down army, and several other guests:

[The consul] introduced the topic of married women and after counting how many there were in the room he turned to me:

“Another friend of yours will soon marry,” he said.

“I wonder who this friend might be that he did not trust me enough to tell me,” I replied.

“Myself…. Isn’t that the talk of the town? Why, the General here told me that even at the doge’s …”

“… Absolutely, I was there too. And Graeme’s main point was that having mentioned the rumor to you, you did nothing to deny it.”

“Why should I deny something which at my old age can only go to my credit?”

Andrea had come away from the consul’s rather flustered, not quite knowing whether Smith had spoken to him “truthfully or in jest.” He asked Giustiniana to keep him informed about what she was hearing on her side. “I am greatly curious to know whether there are any new developments.” No one really knew what the consul’s intentions were—whether he was going to propose to Giustiniana or whether he had decided in Betty’s favor. It was not even clear whether he was really interested in marriage or whether he was having fun at everyone’s expense. Giustiniana too found it hard to read Smith’s mind. “He was here until after four,” she reported to her lover. “No news except that he renewed his invitation to visit him at his house in Mogliano and that he took my hand as he left us.”

Andrea feared Smith might be disturbed by the rumors, ably fueled by the Murray clan, that his affair with Giustiniana was secretly continuing, so he remained cautious in his encouragement: perhaps the consul felt he needed more time; his wife, after all, had only recently been buried. Mrs. Anna, however, was determined not to lose the opportunity to further her daughter’s suit, and she eagerly stepped up the pressure.

In the summer months wealthy Venetians moved to their estates in the countryside. As its maritime power had started to decline in the sixteenth century, the Venetian Republic had gradually turned to the mainland, extending its territories and developing agriculture and manufacture to sustain its economy. The nobility had accumulated vast tracts of land and built elegant villas whose grandeur sometimes rivaled that of great English country houses or French châteaux. By the eighteenth century the villa had become an important mark of social status, and the villeggiatura—the leisurely time spent at the villa in the summer—became increasingly fashionable. Those who owned a villa would open it to family and guests for the season, which started in early July and lasted well into September. Those who did not would scramble to rent a property. And those who could not afford to rent frantically sought invitations. A rather stressful bustle always surrounded the comings and goings of the summer season.

Venetians were not drawn to the country by a romantic desire to feel closer to nature. Their rather contrived summer exodus, which Goldoni had ridiculed in a much-applauded comedy earlier that year at the Teatro San Luca,

(#litres_trial_promo) was a whimsical and ostentatious way of transporting to the countryside the idle lifestyle they indulged in during the winter in the city. In the main, the country provided, quite literally, a change of scenery, as if the burchielli, the comfortable boats that made their way up the Brenta Canal transporting the summer residents to their villas, were also laden with the elaborate sets of the season’s upcoming theatrical production.

Consul Smith had been an adept of the villeggiatura since the early twenties, but it was not until the thirties that he had finally bought a house at Mogliano, north of Venice on the road to Treviso, and had it renovated by his friend Visentini. The house was in typical neo-Palladian style—clear lines and simple, elegant spaces. It faced a small formal garden with classical statues and potted lemon trees arranged symmetrically on the stone parterre. A narrow, well-groomed alley, enclosed by low, decorative gates, ran parallel to the house, immediately beyond the garden, and provided a secure route for the morning or evening walk. The consul had moved part of his collection to adorn the walls at his house in Mogliano, including works by some of his star contemporaries—Marco and Sebastiano Ricci, Francesco Zuccarelli, Giovan Battista Piazzetta, Rosalba Carriera—as well as old masters such as Bellini, Vermeer, Van Dyck, Rembrandt, and Rubens. “As pretty a collection of pictures as I have ever seen,”

(#litres_trial_promo) the architect Robert Adam commented when he visited Smith in the country.

The consul had often invited the Wynnes to see his beautiful house at Mogliano. Now, in the late spring of 1756, he renewed his invitation with a more urgent purpose: to pay his court to Giustiniana with greater vigor so that he could come to a decision about proposing to her, possibly by the end of the summer. Mrs. Anna, usually rather reluctant to make the visit on account of the logistical complications even a short trip to the mainland entailed for a large family like hers, decided she could not refuse.

The prospect of spending several days in the clutches of the consul did not particularly thrill Giustiniana. She told Andrea she wished the old man “would just leave us in peace” and cursed “that wretched Mogliano a hundred times.” But Andrea explained to her that Smith’s invitation was a good thing because it meant he was serious about marrying her and was hopefully giving up on the spinsterish Betty Murray. Giustiniana continued to dread the visit—and the role that, for once, both Andrea and her mother expected her to play. Her anguish only increased during the daylong trip across the lagoon and up to Mogliano. But once she was out in the country and had settled into Smith’s splendid house, she rather began to enjoy her part and to appreciate the humorous side of her forced seduction of il vecchio—the old man. The time she spent with Smith became good material with which to entertain her real lover:

I’ve never seen Smith so sprightly. He made me walk with him all morning and climbed the stairs, skipping the steps to show his agility and strength. [The children] were playing in the garden at who could throw stones the furthest. And Memmo, would you believe it? Smith turned to me and said, “Do you want to see me throw a stone further than anyone else?” I thought he was kidding, but no: he asked [the children] to hand him two rocks and threw them toward the target. He didn’t even reach it, so he blamed the stones, saying they were too light. He then threw more stones. By that time I was bursting with laughter and kept biting my lip.

The visit to Mogliano left everyone satisfied, and even Giustiniana returned in a good mood. Smith was by now apparently quite smitten and intended to continue his courtship during the course of the summer. As this would have been impossible if the Wynnes stayed in Venice, he suggested to Mrs. Anna that she rent from the Mocenigo family a pleasant villa called Le Scalette in the fashionable village of Dolo on the banks of the Brenta, a couple of hours down the road from Mogliano. Smith himself handled all the financial transactions, and since the rental cost would have been high for Mrs. Anna it is possible that he also covered part of the expenses.

Needless to say, Giustiniana was not happy about the arrangement. It was one thing to spend a few days at Mogliano, quite another to have Smith hovering around her throughout the summer. Meanwhile, where would Andrea be? When would they be able to see each other? She could not stand the idea of being separated from her lover for so long. Andrea again tried to reassure her. There was nothing to worry about: it would probably be simpler to arrange clandestine meetings in the country than it was in town. He would come out as often as possible and stay with trusted friends—the Tiepolos had a villa nearby. He would visit her often. It would be easy.

In the meantime Andrea decided he needed to spend as much time as possible with the consul in order to humor him, allay his suspicions, and steer him ever closer toward a decision about Giustiniana. It soon became apparent that the consul, too, wished to keep his young friend close to him. He said he wanted Andrea at his side to deal with his legal and financial affairs but he was probably putting him to the test, observing him closely to see if he still loved Giustiniana. Never before had he seemed so dependent on him. The two of them became inseparable—an unusual couple traveling back and forth between Venice and Mogliano, where Smith’s staff was preparing the house for the summer season, and making frequent business trips to Padua.

Giustiniana was left to brood over her future alone. She complained about Andrea’s absences from Venice and dreaded the uncertainty of her situation. She did not understand his need to spend so much time with that “damned old man.” She felt they were “wasting precious time” that they could be spending together. Yet her reproaches always gave way to words of great tenderness. During one of Andrea’s overnight trips to the mainland with the consul, she wrote:

You are far away, dear Memmo, and I am not well at all. I am happier when you are here in town even when I know we won’t be speaking because I always bear in mind that if by happy accident I am suddenly free to see you, I can always find a way to tell you. You might run over to see me; I might see you at the window…. And so the time I spend away from you passes less painfully…. But days like this one are very long indeed and seem never to end…. Though I must say there have been some happy moments too, as when I woke up this morning and found two letters from you that I read over and over all day. They gave me so much pleasure…. I still have other letters from you, which I fortunately have not yet returned to you—those too were brought out and given a “tour” today. And your portrait—oh, how sweetly it occupied me! I spoke to it, I told it all the things that I feel when I see you and I am unable to express to you when I am near you…. My mother took me out with her to take some fresh air, and we went for a ride ever so lazily down the canal. And as by chance she was as quiet as I was, I let myself go entirely to my thoughts. Then, emerging from those thoughts, I looked around eagerly, as if I were about to run into you. Every time I saw a boat that seemed to me not unlike yours, I couldn’t stop believing that you might be in it. The same thing happened when we got back home—a sudden movement outside brought me several times to the window where I always sit when I hope to see you…. The evening hours were very uncomfortable. We had several visitors, and I could not leave the company. But in the end they did not bother my heart and thoughts so much because I went to sit in a corner of the room. Now, thank God, I have retired and I am with you with all my heart and spirit. This is always the happiest moment of the evening for me. And you, my soul, what are you doing in the country? Are you always with me? Tonnina now torments me because she wants to sleep and is calling me to bed. Oh, the fussy girl! But I guess I must please her. I will write to you tomorrow. Wouldn’t it be sweet if I could dream I was with you? Farewell, my Memmo, farewell. I adore you…. Memmo, I always, always think of you, always, my soul, yes, always.

As the villeggiatura approached, Giustiniana’s anxiety increased. Andrea still spent most of his time with the consul, working for their future happiness, as he put it. But there was no sign that the consul was any closer to a decision. Furthermore, the idea of spending the summer in the countryside deceiving the old man disconcerted her. She grew pessimistic and began to fear that nothing good would ever come of their cockamamie scheme. Andrea was being unrealistic, she felt, and it was madness to press on: “Believe me, we have nothing to gain and much to lose…. We are bound to commit many imprudent acts. He will surely become aware of them and will be disgusted with both you and me. You will have a very dangerous enemy instead of a friend. As for my mother, she will blame us as never before for having disrupted what she believes to be the best plan she ever conceived.” The two of them carried on regardless, Giustiniana complained—she by ingratiating herself to the consul every time she saw him “as if I were really keen to marry him,” thereby pleasing her mother to no end, and Andrea by “lecturing me all day that I should take him as a husband.” But even if she did, even if the consul, at the end of their machinations, asked her to marry him and she consented, did Andrea really think things would suddenly become easier for them or that the consul would come to accept their relationship? “For heaven’s sake, don’t even contemplate such a crazy idea. Do you believe he would even stand to have you in his house or see you next to me? God only knows the scenes that would take place and how miserable my life would become, and his and yours too.”

In June, as Giustiniana waited for the dreaded departure to the countryside, Andrea’s trips out of town increased. There was more to attend to than the consul’s demands: his own family expected him to pay closer attention to the Memmo estates on the mainland now that his uncle was dead. As soon as he was back in Venice, though, he immediately tried to comfort Giustiniana by reiterating the logic behind their undertaking. He insisted that there was no alternative: the consul was their only chance. He argued for patience and was usually persuasive enough that Giustiniana, by her own admission and despite all her reservations, would melt “into a state of complete contentment” just listening to him speak.

Little by little she was beginning to accept the notion that deception was a necessary tool in the pursuit of her own happiness. But the art of deceit did not come naturally to her. When she was not in Andrea’s arms, enthralled by his reassuring words, her own, more innocent way of thinking quickly took over again, and she would panic: “Oh God, Memmo, you paint a picture of my present and my future that makes me tremble. You say Smith is my only chance. Yet if he doesn’t take me, I lose you, and if he does take me, I can’t see you. And you wish me to be wise…. Memmo, what should I do? I cannot go on like this.”

“Ah, Memmo, I am here now and there is no turning back.”

In early July, after weeks of preparations, the Wynnes had finally traveled across the lagoon and up the Brenta Canal and had arrived at Le Scalette, the villa the consul had arranged for them to rent. The memory of her tearful separation from Andrea in Venice that very morning—the Wynnes and their small retinue piling onto their boat on the Grand Canal while Andrea waved to her from his gondola, apparently unseen by Mrs. Anna—had filled Giustiniana’s mind during the entire boat ride. She had lain on the couch inside the cabin, pretending to sleep so as not to interrupt even for an instant the flow of images that kept her enraptured by sweet thoughts of Andrea. Once they arrived at the villa and had settled in, she cast a glance around her new surroundings and had discovered that the house and the garden were actually very nice and the setting on the Brenta could not have been more pleasant. “Oh, if only you were here, how delightful this place would be. How sweetly we could spend our time,” she wrote to him before going to bed the first night.

The daily rituals of the villeggiatura began every morning with a cup of hot chocolate that sweetened the palate after a long night’s sleep and provided a quick boost of energy. It was usually served in an intimate setting—breakfast in the boudoir. The host and hostess and their guests would exchange greetings and the first few tidbits of gossip before the morning mail was brought in. Plans for the day would be laid out. After the toilette, much of which was taken up by elaborate hairdressing in the case of the ladies, the members of the household would reassemble outdoors for a brief walk around the perimeter of the garden. Upon their return they might gather in the drawing room to play cards until it was time for lunch, a rather elaborate meal that in the grander houses was usually prepared under the supervision of a French cook. Afternoons were taken up by social visits or a more formal promenade along the banks of the Brenta, an exercise the Venetians had dubbed la trottata. Often the final destination of this afternoon stroll was the bottega, the village coffeehouse where summer residents caught up with the latest news from Venice. After dinner, the evening was taken up by conversation and society games. Blindman’s bluff was a favorite. In the larger villas there were also small concerts and recitals and the occasional dancing party.

Giustiniana did not really look forward to any of this. As soon as she arrived at Le Scalette she was seized by worries of a logistical nature, wondering whether it would really be easier for her to meet Andrea secretly in the country than it had been in Venice. She looked around the premises for a suitable place where they could see each other and immediately reported to her lover that there was an empty guest room next to her bedroom. More important: “There is a door not far from the bed that opens onto a secret, narrow staircase that leads to the garden. Thus we are free to go in and out without being seen.” She promised Andrea to explore the surroundings more thoroughly: “I will play the spy and check every corner of the house, and look closely at the garden as well as the caretaker’s quarters—everywhere. And I will give you a detailed report.”

The villa next door belonged to Andrea Tron, a shrewd politician who never became doge but was known to be the most powerful man in Venice (he would play an important role in launching Andrea’s career). Tron took a keen interest in his new neighbors. As an old friend of Consul Smith, he was aware that the death of Smith’s wife had created quite an upheaval among the English residents. Like all well-informed Venetians, he also knew about Andrea and Giustiniana’s past relationship and was curious to know whether it might still be simmering under the surface. He came for lunch and invited the Wynnes over to his villa. Mrs. Anna was pleased; it was good policy to be on friendly terms with such an influential man as Tron. She encouraged Giustiniana to be sociable and ingratiating toward their important neighbor. In the afternoon, Giustiniana took to sitting at the end of the garden, near the little gate that opened onto the main thoroughfare, enjoying the coolness and gazing dreamily at the passersby. Tron would often stroll past and stop for a little conversation with her.

Initially Giustiniana thought his large estate might prove useful for her nightly escapades. She had noticed that there were several casini on his property where she and Andrea could meet under cover of darkness. But thanks to her frequent trips to the servants’ quarters, where she was already forming useful alliances, she had found out that Tron’s casini were “always full of people and even if there should be an empty one, the crowds next door might make it too dangerous” for them to plan a tryst there.

In the end it seemed to her more convenient and prudent to make arrangements with their trusted friends, the Tiepolos: their villa was a little further down the road, but Andrea could certainly stay there and a secret rendezvous might be engineered more safely. Giustiniana even went so far as to express the hope that they might be able to replicate in the countryside “another Ca’ Tiepolo,” which had served them so well back in Venice. She added—her mind was racing ahead—that when Andrea came out to visit it would be best “if we meet in the morning because it is easy for me to get up before everyone else while in the evening the house is always full of people and I am constantly observed.”

As Giustiniana diligently prepared the ground for a summer of lovemaking, she did wonder whether “all this information might ever be of any use to us.” Andrea was still constantly on the move, a fleeting presence along the Brenta. When he was not with the consul at Mogliano, he was traveling to Padua on business, visiting the Memmo estate, or rushing back to Venice, where his sister, Marina, who had not been well for some time, had suddenly been taken very ill. Giustiniana might hear that Andrea was in a neighboring village, on his way to see her. Then she would hear nothing more. Every time she started to dream of him stealing into her bedroom in the dead of night or surprising her at the village bottega, a letter would reach her announcing a delay or a change of plans. So she waited and wrote to him, and waited and wrote:

I took a long walk in the garden, alone for the most part. I had your little portrait with me. How often I looked at it! How many things I said to it! How many prayers and how many protestations I made! Ah, Memmo, if only you knew how excessively I adore you! I defy any woman to love you as I love you. And we know each other so deeply and we cannot enjoy our perfect friendship or take advantage of our common interests. God, what madness! Though in these cruel circumstances it is good to know that you love me in the extreme and that I have no doubts about you: otherwise what miserable hell my life would be.

A few days later she was still on tenterhooks:

I received your letter just as we got up from the table and I flew to a small room, locked myself in, and gave myself away to the pleasure of listening to my Memmo talk to me and profess all his tenderness for me and tell me about all the things that have kept him so busy. Oh, if only you had seen me then, how gratified you would have been. I lay nonchalantly on the couch and held your letter in one hand and your portrait in the other. I read and reread [the letter] avidly, and for a moment I abandoned that pleasure to indulge in the other pleasure of looking at you. I pressed one and the other against my bosom and was overcome by waves of tenderness. Little by little I fell asleep. An hour and a half later I awoke, and now I am with you again and writing to you.

Andrea was finally on his way to see Giustiniana one evening when he was reached by a note from his brother Bernardo, telling him that their sister, Marina, was dying. Distraught, he returned to Venice and wrote to Giustiniana en route to explain his change of plans. She immediately wrote back, sending all her love and sympathy:

Your sister is dying, Memmo? And you have to rush back to Venice? … You do well to go, and I would have advised you to do the same…. But I am hopeful that she will live…. Maybe your mother and your family have written to you so pressingly only to hasten your return…. If your sister recovers, I pray you will come to see me right away…. And if she should pass away, you will need consolation, and after the time that decency requires you will come to seek it from your Giustiniana.

In this manner, days and then weeks went by. Eventually, Giustiniana stopped making plans for secret encounters. There were moments during her lonely wait when she even worried about the intensity of her feelings. What was going on in his mind, in his heart? She had his letters, of course. He was usually very good about writing to her. But his prolonged absence disoriented her. She needed so much to see him—to see him in the flesh and not simply to conjure his image in a world of fantasy. “I tremble, Memmo, at the thought that my excessive love might become a burden on you,” she wrote to him touchingly. “… I have no one else but you … Where are you now, my soul? Why can’t I be with you?”

While she longed for Andrea to appear in the country, Giustiniana also forced herself to be graceful with the consul. He called on the Wynnes regularly, coming by for lunch and sometimes staying overnight at Le Scalette, throwing the household into a tizzy because of his surprise arrivals and the late hours he kept. He took Giustiniana out on walks in the garden and spent time with the family, lavishing his attention on everyone. There was no question in anybody’s mind that the old man was completely taken with Giustiniana and that he was courting her with the intention of marriage. Even the younger children had come to assume that the consul had been “tagged” and already “belonged” to their older sister, as Giustiniana put it in her letters to Andrea.

As she waited for her lover, Giustiniana watched with mild bewilderment the restrained embraces between her sister Tonnina and her young fiancé, Alvise Renier, who was summering in a villa nearby. “Poor fellow!” she wrote to Andrea. “He takes her in his arms, holds her close to him, and still she remains indolent and moves no more than a statue. Even when she does caress him she is so cold that merely looking at her makes one angry. I don’t understand that kind of love, my soul, because you set me on fire if you so much as touch me.” She was being a little hard on her youngest sister. After all, Tonnina was only thirteen and Alvise little older than that; it was a fairly innocent first love. But of course every time Giustiniana saw them together she longed to be in the arms of her impetuous lover.

Mrs. Anna, unaware of the heavy flow of letters between Le Scalette and Ca’ Memmo, could not have been more pleased at how things were developing. With Andrea out of the way, the consul seemed increasingly comfortable with the idea of marrying Giustiniana. It was not unrealistic to expect a formal proposal by the end of the season. The other summer residents followed with relish the comings and goings at the Wynnes’. The consul’s visits were regularly commented upon at the bottega in Dolo, as was Andrea’s conspicuous absence. Were they still seeing each other behind the consul’s back, or had their love affair finally succumbed to family pressures? Giustiniana’s young Venetian friends often put her on the spot when she appeared to fetch her mail. However circumspect she had to be, she could not give up the secret pleasure of letting people know, in her own allusive way, that she still loved Andrea deeply. “Today we were talking about how the English run away from passions whilst the Italians seem to embrace them,” she reported. “I was asked somewhat maliciously what I thought of the matter. I replied that life is quite short and that a well-grounded passion for a sweet and lovable person can give one a thousand pleasures. In such cases, I said, why run away from it? The same person pressed on: ‘What if that passion is strongly opposed or if it is hurtful?’ I answered that once a passion is developed it must always be sustained…. Must I really care about what these silly people think? I have too much vanity to disown in public a choice that I have made.”

The consul’s repeated visits—and Andrea’s continued absence—created an air of inevitability about her future marriage that took its toll on Giustiniana. In public, she did her best to put on a brave front. But as soon as she was alone the gloomiest premonitions took hold of her. The hope that when it was all over—when the marriage had taken place—she would be free to give herself completely to the man she loved sustained her through the performance she was putting on day after day. But she could not rid herself of the fear that for all their clever scheming, once the consul married her she would not be able to see Andrea at all. As an English friend summering by the Brenta whispered to her one day, “I know my country well, and I am quite sure the first person Smith will ban from his house will be Memmo.” She wrote to Andrea:

Alas, I know my country too! So what is to be done? Wait until he dies to be free? And in the meantime? And afterward? He might live with me for years, while I cannot live without you for a month…. True, any other husband would stop me from seeing you without having the advantages Smith has to offer, including his old age…. But everything is so uncertain, and it seems to me that the future can only be worse than the present. Of course it would be wrong for the two of us to get married. I wouldn’t want your ruin even if it gave me all the happiness I would feel living with you. No, my Memmo! I love you in the most disinterested and sincerest way possible, exactly as you should be loved. I do not believe we shall ever be entirely happy, but all the same I will always be yours, I will adore you, and I will depend on you all my life…. So I will do what pleases you, [but remember] that if Smith were to ask for my hand and my Memmo were not entirely happy about it I would instantly abandon Smith and everything else with him, for my true good fortune is to belong to you and you alone.

In August Marina’s health briefly improved and Andrea was finally free to go to the country to see Giustiniana. He was not well—still recovering from a bad fever that had forced him to bed. But he decided to make the trip out to Dolo anyway and take advantage of the Tiepolos’ open invitation. Giustiniana was in a frenzy of excitement. “Come quickly, my heart, now that your sister’s condition allows you to…. I would do anything, anything for the pleasure of seeing you.” It was too risky for Andrea to visit her house, so she had arranged to see him in the modest home of the mother of one of the servants, thanks to the intercession of a local priest in whom she had immediately confided. “I went to see it, and I must tell you it’s nothing more than a hovel,” she warned, “but it should suffice us.” Alternatively, they could meet in the caretaker’s apartment, which was reached “by taking a little staircase next to the stables.”

These preparations were unnecessary. Andrea arrived by carriage late in the night, exhausted after a long detour to Padua he had made on behalf of the ever-demanding consul. He left his luggage at the Tiepolos’ and immediately went off to surprise Giustiniana by sneaking up to her room from the garden.

The following morning, after lingering in bed in a joyful haze, she scribbled a note and sent it to Andrea care of the Tiepolos: “My darling, lovable Memmo, how grateful I feel! Can a heart be more giving? Anyone can pay a visit to his lover. But the circumstances in which you came to see me last night, and the manner and grace you showed me—nobody, nobody else could have done it! I am so happy and you are wonderful to me. When will I be allowed to show you all my tenderness?”

Giustiniana fretted about Andrea’s health. He had not looked well, and she feared a relapse: “You have lost some weight, and you looked paler than usual…. I didn’t want to tell you, my precious, but you left me worried. For the love of me, please take care of yourself. How much you must have suffered riding all night in the stagecoach, and possibly still with a fever…. My soul, the pleasure of seeing you is simply too, too costly.” Yet she was so hungry for him after his long absence that she could hardly bear not to see him now that he was so close: “Maybe you will come again this evening…. Do not expose yourself to danger, for I would die if I were the cause of any ailment…. If you have fully recovered, do come, for I shall be waiting for you with the greatest impatience, but if you are still not well then take care of yourself, my soul. I will come to see you; I will … ah, but I cannot. What cruelty!”