Полная версия

Полная версияConstantinople and the Scenery of the Seven Churches of Asia Minor

Among the Franks who flock to Constantinople in search of fortune, there is a large proportion of Italians. Many of them have received an education at Padua, or other Italian universities, taken out degrees in medicine, and so come qualified for the practice of it. Many adopt the profession after their arrival, as the most lucrative and easiest means of living. It requires but slight knowledge to be superior to the native hakims, and the acuteness and sagacity of these versatile Italians supply every deficiency. Among these was Lorenzo, a native of Florence. He had acquired some reputation by the practice of his art among the Franks; and the Turks, ever eager to avail themselves of the superior lights of Europeans when health is concerned, soon gave him the preference over their own doctors. It happened that the eldest son of the reigning Sultan, Abdul Hamed, fell sick; and the reputation of this Frank physician was so high, that he was sent for to the Seraglio. The boy recovered, and nothing could exceed the gratitude of the father. He built for the physician a large house in Pera; conferred on him a beautiful kiosk and chifflik at St. Stephano, for his country residence; and, in order to secure his future practice, he appointed him Hakim Bashi, or “principal physician” to the Seraglio.

These gifts and this situation, not only gratified his cupidity, but unfortunately excited his ambition also. His patronage became unbounded. The appointment and deposition of pashas, the banishment or recall of vizirs, in which the secret influence of the Seraglio became every day available, were exercised by him, and the fanaticism of the Moslem was forgotten, when he became indebted to this giaour for the highest services. On the death of his patron, Abdul Hamed, his successors, Selim and Mustapha continued their favour, and treated him with the same confidence and indulgence; and when the young and inexperienced Mahmoud succeeded, it was supposed he would exercise over him the same influence. He was now arrived at the age of eighty. He was about to withdraw from the care and anxiety such a life imposed upon him, with credit and reputation, and devote what remained of it to retirement and peace, when in an evil hour he was induced to engage in one more of those court intrigues from which his Italian dexterity had so often extricated him. The young Sultan notified to him, that he would have no one intermeddle in his affairs, and cautioned him to desist. He would not take warning, and his summary death was resolved on.

By the capitulations entered into with foreign powers, every Frank subject is under the protection of the representative of that state to which he belongs, and amenable only to its tribunal. Lorenzo therefore could not be dealt with as a Raya, and put to death by the mandate of the Sultan. It would have excited the whole diplomatic corps of Pera, who would make a common cause to support their privileges and immunities. It was therefore necessary to dispose of him in another manner. He was sent for one evening by the Capitan Pasha, to see one of his family, taken suddenly ill; and the way from Pera, where his house was, to the palace of the pasha, on the harbour, lay through this cemetery. He took with him his Capi Tchocadar, who always attended him to the Seraglio, and proceeded to pay his visit, apprising his family that he would return when he had prescribed for his patient. The Turks retire to rest early, and the period was past when he was expected home. His way led through a place infamous for outrage of all kind, and the apprehensions of his family were considerably excited. He did not return during the night, and at the dawn of morning they proceeded to meet him along the avenue leading through Cassim Pasha to the Capitan Pasha’s palace. In a small dell, where the road winds down a steep, they stumbled on two bodies−one was that of the Tchocadar, and the other that of Lorenzo. They were quite dead, with the marks of the bowstring, with which they had been strangled, round their necks. The valuables they had about their persons were untouched, and it was hence inferred that it was the work of no robbers. The usual legal process of inquiry was taken by the Austrian internuncio, and the conclusion formed from the proceedings was, that the assassin was no other than the young Sultan himself, who had caused him and his attendant to be executed in the palace of the Capitan Pasha, and the bodies laid where they were found; and the property was not taken from them, that it might not be supposed they fell victims to common assassins, but to that terrible, mysterious vengeance, which suffered no man to escape that once excited it. The Turkish ministry, however, affected to believe it was a common death by midnight murderers in a dangerous place; and to prevent the recurrence of such accidents, a small edifice was built, and a guard established on the spot, which yet remain. A guard-house here is not like one in Europe, from whence a passenger is rudely repulsed. Beside it is a small caffinet, with benches, on which he is invited to repose; and while he partakes of the refreshments offered him, some hoary-headed sentinel enters into conversation with him, and tells him the melancholy fate of Lorenzo the Hakim Bashi.

On the right of Cassim Pasha begin the suburbs of Piri Pasha, so called from a very distinguished event in Turkish history. When the knights of the holy sepulchre were driven from Palestine, they took refuge in the island of Rhodes, where they fortified themselves, still lingering in the vicinity of that holy place, which they vainly attempted to hold, and in the hope of keeping alive the expiring spark of Christianity in the East. But Soliman the Magnificent was resolved to extinguish it utterly, and made stupendous preparations to dislodge its gallant defenders from their last strong-hold. An army of 150,000 men was embarked in a fleet of 400 ships, and proceeded to exterminate this devoted community, shut up on their insulated rock. The first notice they received of their intended fate, was from fires lighted on the opposite coast of Lycia. A galley was despatched, to ascertain the cause of these unusual beacons, when a packet was thrown on board directed to the grand master. It was opened, and found to contain a summons of unconditional submission, and the surrender of the place. To oppose the countless multitudes who rushed to this unexpected attack, 6000 men alone were found on the island, and they prepared to defend it. With incredible efforts they resisted every assault, and the great Sultan himself, impatient of delay, hastened from Constantinople, to animate his troops by his presence. It was fruitless. The assailants, under the eye of their sovereign, were repulsed, leaving the bodies of 20,000 of their companions weltering on the rocks. The commanders were deposed and punished, and the enraged and disappointed Sultan conferred the whole direction of the siege on his favourite Piri Pasha. He desisted from sanguinary and ineffectual assaults, and proceeded by sapping the fortress. The most distinguished engineers in Europe were invited by the magnificent Sultan, and the island was perforated by fifty-five mines, sufficient to blow the fortress and the rock on which it stood, into the air; but they were met by counter-mines, and harmlessly exploded. At length, worn out by famine and fatigue, exhausted but not subdued, the gallant garrison were incapable of further resistance, and this handful of Christians, the last and only valuable remnant of the insane Crusaders, retired to another island, farther west, still destined for two centuries more to defend the cause of the Gospel farther west against the encroaching of the Koran. The distinguished Turk who effected this conquest of Rhodes, gave his name to this suburb of Constantinople; and the district of Piri Pasha recalls to the Moslem the expulsion of the last remnant of Christianity from the East.

On the conquest of Rhodes, Soliman erected his splendid mosque on the summit of the highest of the seven hills of the capital, and his faithful pasha determined to follow his example, but in a less ostentatious form. He knew how dangerous it was to be his rival, so he became his humble imitator. In the low district assigned to him, a mosque rears its unpretending head, simple in its aspect, but still distinguished by its beauty and architectural ornaments. It strikingly deviates from the usual style of Oriental building, as it is elevated on light arcades, supported on pillars, having three equal colonnades, in each division.

Near this is the Ain Ali Kasa Seraï, or “The Palace of Mirrors.” When Achmed III., in 1715, recovered the Morea from the Venetians, they wished to conciliate him by some valuable present. They were then famous for the manufacture of mirrors, and they sent him the largest specimens that ever had been made. Achmed accepted them, and built a palace in this place for their reception.

The great fire kindled by the discontented adherents of the Janissaries in 1831, commenced at Sakiz Aghatz in this district. The whole of it was consumed, including the palaces of all the European embassies, as well as that of the Capitan Pasha. The remains of this last still stand on an eminence near the Arsenal, consisting of a line of arcades, resembling an aqueduct, flanked by clusters of little towers: it was in this place the murder of the Hakim Bashi was perpetrated, and, as long as it stands, it will keep alive the memory of the unfortunate Lorenzo.

Our illustration presents the city as it appears from this district. The Mosque of Sulimanie towering in the centre, and the aqueduct of Valens uniting the hill on which it stands with the opposite. But the most conspicuous and novel object is the Buyuk Tchekmadgé, or “Great Bridge,” which Mahmoud II. caused to be thrown across the harbour.25 This structure, so necessary for the communications of a great city, had been called for ever since Constantine had made this the capital of the Roman empire. The peninsula of Pera, containing 200,000 inhabitants, was an important part of the city; yet the only passage to it by land, was a bridge over the Barbyses, by a circuit of nine or ten miles. Among the obstacles to erecting a bridge across the harbour, was the immense number of caïquegees, or “boatmen,” who obtained their living by the many ferries. On various pressing occasions the government had attempted to avail itself of their services in manning the fleet; but they resisted with obstinancy, and, notwithstanding the unmitigated despotism and unsparing ferocity of the Sultan, it was considered too hazardous to exasperate this fierce democracy. With the same obstinacy they opposed the building of a bridge, which would interfere with their means of living. But when the terrible and energetic sovereign had cut off the Janissaries, all effectual resistance to any of his plans of innovation was removed, so he determined on uniting the divided parts of his great city. Among the modes by which many of his improvements were effected, was availing himself of the services of some rich subject. When navigation by steam was introduced into Europe, Mahmoud ardently wished for its adoption in Turkey. He was one morning agreeably surprised, by seeing a noble steam-boat moored under the Seraglio, and he was told it was the gift of Casas Aretine, a rich Armenian. In the same way an individual completed for him this bridge, when the caïquegees no longer dared to oppose it.

On the 20th of October, 1837, it was opened for passengers, and the ceremony was attended with another extraordinary innovation on Turkish manners. He not only attended himself with his sons, but his harem was thrown open, and ladies dressed in their gayest attire appeared in their arrhubas, mixed with the spectators, and mingled in the fête with all the freedom and gaiety of a similar event in Paris or London. The novelty and brilliancy of the spectacle form a new era in the society of the Moslem capital. As it was almost the only level way in the city, it became a favourite carriage promenade; and the Sultan himself was seen to abandon his caïque, and frequently drive across it in an European carriage.

VILLAGE OF ROUMELIA, NEAR ADRIANOPLE

J. Salmon Drawn from Nature by F. Hervé. J. C. Bentley.

The district of ancient Thrace is sometimes called Romania, but more properly, Roumelia, from the Turkish name Roum Eli, “the country of the Romans.” It extended from the Euxine Sea to the river Strymon, and from Mons Hemus to the Propontis and Egean, which limits it has retained through all its vicissitudes to the present day. Byzantium, or Constantinople, is its former, as it is its present capital. The ancient Thracians were distinguished for their ferocity, and the poets have reported it as the theatre of many scenes of cruelty. Here it was that their king, Diomedes, fed his horses on human flesh, casting every stranger he found into their mangers, to be devoured alive; and here it was that the poet Orpheus, while lamenting the loss of his beloved Eurydice, was torn to pieces by the women, and his head cast into the Hebrus; and he who was represented to soothe tigers, soften rocks, and lead lofty oaks by his song, could not charm into humanity the Thracian ladies. In less fabulous times, their barbarism is unfortunately too well authenticated. It was the region where they offered up human victims as grateful offerings to their gods, and that from whence the Roman people obtained their theatrical assassins; so that the names of Thracian and gladiator are synonymous in their language: and such was the horrid delight taken in their exhibition, that from one thousand to fifteen hundred of those barbarians are reported to have been seen dead or dying, by each others swords, at the same moment, on the bloody stage, for the amusement of the assembled citizens of Rome.

The original barbarians of this region were amalgamated with various people as barbarous as themselves, who were driven from their own deserts, and invited to settle there. The Bastarnæ, a nation from the banks of the Rhine, were located here by the Emperor Probus, who attempted to instruct them in the ways of civilized life; but the intractable savages rejected the instruction, and, by repeated rebellions and insurrections, devastated the country they were allowed to settle in. In the reign of Valens, another nation was transported hither. The Goths were assaulted by the Huns, whom they represented as an unknown and monstrous race of savages, and they supplicated permission to escape from their ferocity by migrating into Thrace, and occupying the vast uncultivated plains then waste and unproductive. This second immigration was permitted; and these barbarians, like the former, ungratefully rebelled against their benefactors.

To this mingled population was finally added that of the Turks. In the year 1363 they crossed the Hellespont, and spread over this region their conquering hordes, adding Oriental ignorance and fanaticism to the catalogue of Thracian qualities. They seem to have even deteriorated the original character they brought with them in this European district. The Thracian Turk is said to be more inhospitable than a Turk in any other place. Travellers frequently fall victims to their intractable jealousy; and should a benighted stranger seek for shelter and protection, he is driven from the door by savage dogs, and fired at by the more savage master from within. And this repulsive conduct extends equally to their own countrymen as to those of other nations. Tartar couriers, or Turkish travellers, overtaken by night or storm in the winter, have been frequently found dead in the snow, near the inhospitable house where they had been denied a shelter. Their conduct, in this respect, forms a strong contrast with that of the kind and hospitable Bulgarians, who are spread over part of this district, and mingled with the Moslem population.

The general aspect of the country, from the Balkans to the sea, is exceedingly beautiful. Swelling downs, expanded to an interminable distance, bounded only by the horizon. These are covered with a rich green sward, capable of any purpose of cultivation, either tillage or pasture. Occasionally the downs are intersected by depressions, which form winding glens, and sometimes a low ridge from the Balkans runs to an immense extent, till it is gradually lost in the plain, affording in its progress a variety of knolls and eminences highly picturesque and beautiful. The country is watered by the Hebrus and its tributary streams, which rising among the snows of the Balkans, and continually augmented by their solution, meander through the plains down to the sea; unceasingly refreshing the thirsty but fertile soil with their copious, cool, and limpid currents. The climate is exceedingly bland and temperate, and the moment a traveller passes the mountains he feels its influence. He ascends the northern side at an advanced season of the year, leaving behind him a country faded in its verdure, denuded of its foliage, and having the hand of winter everywhere impressed upon it. He descends on the southern side, and in a few days finds every thing changed. He breathes a warm temperate air, sees spring and summer blooming around him; the fields are green, the hills are gay, and the romantic woods and copses which clothe them, retain not only their leaves but their flowers also.

But in the midst of these beauties of nature he observes that everything is solitary and deserted. He passes a day’s journey through them, and meets nothing that has life from morning till evening. He sees on the distant horizon something that has the semblance of an inhabited place; he finds, when he approaches, that it is only a cemetery, which indicates that human life had once been there, but has now long since departed. Not a trace of the villages to which they once belonged remains behind, to mark where social man had once existed. Some of these solitary cemeteries are very extensive, and seem to mark the vicinity of a large town and numerous inhabitants; but so completely and so long ago have they been obliterated, that their very names have perished. It is natural for an inquisitive traveller, when he sees a large grave-yard, to ask his Tartar, or surrogee, the name of the city to which it belongs−but the Turk who daily travels by it, shakes his head at the hopeless question, and replies “Allah bilir,” God only knows.

What adds to the singularity and solitude of these plains, is the multitude of conical mounds which are everywhere scattered over them. These are lofty, and evidently artificial heaps, thrown up at some remote period by human labour, and to answer some purpose. They exactly resemble those mounds on the opposite coast of Asia, on the plains of Troy, which are supposed to be the tombs of heroes who fell during the siege, and the monuments erected over them, to mark the spot where their bodies are deposited. They are both equally called tepé in Asia and Europe, which is supposed to be a corruption of the Greek word ταϕος, by which the tombs of heroes were designated, and this coincidence renders it probable they both had the same origin. They are sometimes so numerous, that eight or ten appear at once, and the traveller passes close to them in succession, while whole ranges of them are seen marking the outline of the distant horizon. The supposition that they are tombs, adds considerably to the sense of solitude in these lonely regions. The traveller supposes himself passing through a vast grave-yard of several hundred miles in extent, the receptacle of human bodies, where, from the earliest ages, the kings, and heroes, and great ones of their nation are reposing in solitary magnificence.

While the fields are abandoned and agriculture is neglected, there is no art substituted or manufacture pursued, to engage the corresponding scanty population. The gold mines of Thrace were formerly so rich as to yield Philip of Macedon the value of £200,000 annually; an immense sum in those days, which enabled him to corrupt the patriot orators of Athens, and to boast that no city could resist him, that had a breach wide enough to admit an ass laden with the produce of these mines. They are unproductive to the Turks; and while they might raise a richer harvest of golden grain on those plains close to their capital, they are indebted to Odessa, and the permission of their enemies, the Russians, for the daily bread of Constantinople.

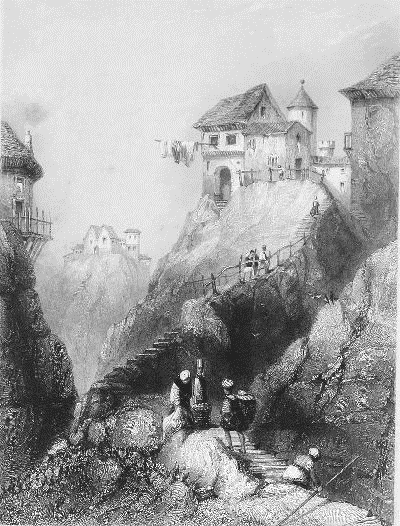

Our illustration presents, not the general appearance of the country, but one of those wandering ridges, which running from the high Balkans, like the fibres of some gigantic tree, are the branches of those roots by which they seem fastened to the level ground, and its picturesque and romantic features are different from the usual character of the level country. The plain from hence to Adrianople, and to the sea, is generally a flat surface of immense extent. These village-crowned peaks are called, both here and in the neighbouring country of Macedon, meteors, or “appearances in the air.” They are usually chosen as the site of Greek convents, and sometimes ascended by a basket let down with cords, in which the visitor is drawn up. The sides of the hills, in every accessible spot, are covered with vineyards, from which the city of Adrianople is supplied with grapes of an excellent quality.

CAVALRY BARRACKS ON THE BOSPHORUS

T. Allom. S. Fisher.

The feudal tenure by which the conquered lands were held by those to whom the victorious Sultan assigned them, were called Zaims and Timariots. This obliged every man to furnish a certain number of mounted followers, to take the field when called upon, and formed the first cavalry enrolled for military service by the Turks. But to these were added more efficient bodies, paid from the treasury, and enrolled as regular troops−these were called Selictarli and Spahi.

Selictarli, which literally means “men of the sword,” were the oldest and earliest corps, and owed their origin to Ali, the fourth caliph of the Osmanli race. To their care was entrusted the defence of the sacred person of the Sultan; they formed his immediate body-guard, and were distinguished by a standard of bright red as their ensign. But in the reign of Mahomet III., during a sanguinary combat, they were seized with a sudden panic, and abandoned their sovereign. Unable to rally the Selictars, he called on the grooms who attended their horses, who at once obeyed his summons, and rescued him from the danger. To punish the one, and reward the other, he formed a new corps of these grooms, conferred upon them the scarlet standard, while their masters were obliged to adopt one of yellow, as a mark of their degradation; and he called his new corps “Spahis,” that is, simple cavaliers, without Zaim or Timar.

On their first appointment, their arms were bows and arrows, with sabres, and a lance called a dgerid. They preferred these to pistols or carbines, for, said they, “firearms expend themselves in the air, but sabres and lances prostrate on the ground.” The dgerid was a short lance, which they darted with unerring aim at full speed; to this day, representations of their ancient combat with this weapon, form a distinguished part of their athletic sports. They hurl pointless lances at each other as they pass at full speed, and, stooping to the ground from their saddle-bow, recover them without dismounting, or slackening their pace; to these were attached certain adventurers called Gionuli, or “volunteers.” They watched the death of a Timariot, and immediately took his place, and succeeded to his Timar. So desperate and sanguinary were the combats, on one occasion, that in a few hours the same Timar passed through seven gionuli, who were all brief proprietors of a landed estate in succession, before they died. It remained in possession of the eighth who survived the battle.

But the most desperate and extraordinary of this cavalry, are the Delhi, or Deliler, which literally means “madmen,” a name their conduct well entitles them to bear. They are generally recruited from Servia and Croatia, and are of robust stature, and fierce and formidable aspect. This they endeavour to increase by their dress: their helmets are formed of a leopard’s head and jaws, with the skin hanging down to their shoulders; and this is surmounted by the beak, wings, and tail of an eagle, united with threads of iron. Their vests are skins of lions, and their trousers the hides of bears with the shaggy hair outside. They despise the crooked sabre of the Spahi, but carry a target and a serrated lance of great weight and size. These men rush on their enemies with the most reckless impetuosity; and, should any of them hesitate at the most hopeless and desperate attack, they are dishonoured for ever.