Полная версия

Полная версияConstantinople and the Scenery of the Seven Churches of Asia Minor

Beyond the walls of the city, about half-a-mile from the Selyvria gate, approaching to the sea of Marmora, is one of the most celebrated of these fountains, which, from the earliest period of its dedication to Christianity, has been held in the highest veneration. The tradition of a miracle wrought by its waters in restoring sight to a blind man, attracted the attention of the Greek emperors, and it afterwards became the object of their peculiar care. Leo the Great, in the year 460, first erected a church over it. The emperor Justinian was returning one day from hunting, and perceived a great crowd surrounding it. He inquired into the cause, and learned that a miracle of healing had just been wrought by the waters; so, when he had finished his gorgeous temple to “the Eternal Wisdom of God,” he applied the surplus of his rich materials to adorning this church. It stood for two centuries, an object of wonder and veneration, till it was shattered by an earthquake, when it was finally rebuilt by the empress Irené with more splendour than ever. Such was the sanctity and esteem in which it was held, that imperial marriages were celebrated in it, in preference to Santa Sophia, or other edifices in the city. When Simeon the Bulgarian defeated the Greeks under the walls of the city, he married his son Peter to Maria, the daughter of the emperor Lacapenus, here; and again, the nuptials of the daughter of Cantacuzene with the son of Andronicus Palæologus were celebrated in it with great pomp.

But, besides the sanctity of the place, its natural beauties present considerable attractions. The Byzantine historians describe them in glowing colours: meadows enamelled with flowers of all kinds, gardens filled with the richest fruits, groves waving with the most varied and luxuriant foliage, a balmy air breathing purity and enjoyment, and, above all, a fountain which, to use the language of the times, “the mother of God had endowed with such miraculous gifts, that every bubble that issued from it contained a remedy for every disease.”

This lovely and health-giving place was the resort not only of the pious, but of all who sought recreation in rural scenes. The emperors erected a summer-residence beside the church, and the celebrated region was called “the palace and temple of the fountain.”

When the Turks laid siege to the city, their principal attack was at the gate of St. Romanus, near this spot. The rude soldiers, encamped round it, destroyed its groves, dilapidated its walls, and defiled its fountain; but a traditional anecdote is told, which conferred, in the eyes of the superstitious conquerors, a character as miraculous as that which the Byzantines bestowed upon it. So sure were the infatuated Greeks of Divine assistance to repel their enemies, that they expected the angel Michael every moment to descend with a flaming sword and destroy them. When the Turks made their last successful attack, and entered the city over the body of the emperor, a priest was frying fish in a part of the edifice still standing; and when it was told him the city was taken, he replied, he could as soon believe the fried fish would return to their native element, and again resume life. To convert his incredulity, they did actually spring from the vessel into the sacred fountain beside it, where they swam about, and continue to swim at this day. This circumstance is said to have rendered the place as miraculous in the eyes of the Moslems as the Christians; so they changed the name, to commemorate the miracle, into Baloukli or “the place of the fishes,” into which its former appellative merged, and by which it is now known.

As this was a place held by the Greeks, from the earliest times, in great distinction, and the Turks themselves partook of the impression it caused; it was the object of their attention, when the insurrection broke out in 1821. They rushed in a body to this celebrated place, tore down what of the edifice had been suffered to remain, and attacked the unfortunate persons who had presumed to venture to celebrate their primitive festival. In this state it continued for several years, and the traveller who visited it saw a desecrated ruin, occupied only by a poor Caloyer in his tattered blue tunic, lamenting over the devastation of his sacred enclosure. The miraculous fishes, however, seemed to be the only objects that did not suffer by the sacrilege. They still might be seen darting through the water, and the countenance of the poor priest lightened up with pleasure, when he could find them out, and say, idhoo psari afthenti−look at these fishes, sir.

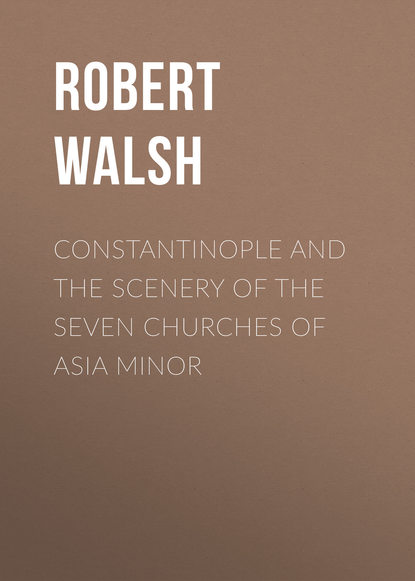

At length, when affairs became settled, and the revolution was completed and recognized, a firman was issued by the sultan, to repair all the Christian churches that had been injured, and this was among the first to which attention was directed. The former celebrity and great sanctity conferred upon it a more than usual interest; and the Russian government, as members of the Greek church, contributed to its re-erection on a more extended plan. It is surrounded by an area, in which is built a residence for the priests of the well. From hence is the approach to the church, which has a certain subterranean character, and is entered by a descent of marble steps. The interior has been finished with much care, indicating considerable anxiety to adorn such an edifice with corresponding ornaments. The walls are covered with a light and glittering coat of gold on white varnish, so as to resemble the finest porcelain China, and present a rich surface to the eye, perfectly dazzling. This effect is heightened by splendid glass lustres suspended from the ceiling, and presented by the emperor Nicholas.

Our illustration presents the church under its characteristic and usual aspect. Before the ornamented screen which separates the nave from the sanctuary, is stretched the sick brought here to be healed after the ablution of the water, by the panayia who presides over it. Another trait of Greek superstition is also displayed: at the entrance to the church is a large case, in which a number of slender tapers are deposited; every male, on coming in, purchases at this counter a taper, which he lights, and bears in his hand to a stand placed before the sanctuary. Here he sticks it on a point prepared for it, and suffers it to burn out, as a necessary part of his devotion. This ceremony is particularly practised by Greek mariners, who thus propitiate the Virgin before they sail. The Greek church, like the Latin, prescribes a formula for blessing those candles, and believe, that whenever the benediction is said over them, they have a power conferred upon them of chasing away demons and evil spirits when they are lighted.

GREEK CHURCH OF SAINT THEODORE, PERGAMUS.

ASIA MINOR

T. Allom. T. A. Friar.

The Hagiography of the modern Greeks resembles, in many respects, the Mythology of their ancestors. Their saints are divided into Megalo and Micro, like the Major and Minor deities of their pagan forefathers. They attribute to them preternatural powers and miraculous gifts, the exercise of which is displayed pretty much in the same manner in both; and there are many of the same name, to each of whom the actions of all are sometimes attributed. The name of Ayos Theodoros is borne by five individuals in the Greek church, who have all festivals in different months in the year; there were three edifices consecrated to them in the capital; and churches bearing their name are found in every part of the empire where a Greek community exists, at this day.

Ayos Theodoros, which the church of Pergamus acknowledges, was called Stratiolites, or “the Soldier.” He was born at Heraclea, and was general under Licinius, the last rival of Constantine the Great. After various acts of valour and services to the state, he was decapitated by the tyrant, in 319, for his attachment to the Christian cause. He was brought by his adherents, to be buried at Apamea, which was thence called Theodoropolis; and pilgrims visited his shrine, and fulfilled vows in “the spiritual meadow” beside it, where many miracles were performed. His personal powers did not cease with his death. Like the twin-brothers, Castor and Pollux, he appeared in battle, and discomfited the enemies of his votaries. Six hundred and fifty years after his death, the wicked Johannes Zemisces, by his aid obtained a signal victory. He is represented in armour with a sword and shield, consonant to his church-militant character. His effigy formed one of the twelve flammulæ on the ensigns of the empire; his shield is preserved in the church at Dalisand, in Asia; his body was brought by Dandolo from Constantinople to Venice, in 1260; but his head was claimed by another place, and deposited at Cajeta.

Other saints, of the same name, had various similar acts attributed to them, and were frequently confounded together. Theodore of Siceon in Galatia, was a prophet, and predicted that Mauricius should be emperor, which accordingly took place; and he was afterwards sent for to the imperial palace, to confer his blessing upon the new royal family. Another Theodore was particularly distinguished for his miracles. In the language of his panegyrist “he expelled devils, healed distempers, and conferred miraculous gifts on all who touched his tomb.” A fourth, seized with prophetic inspiration, and while sailing on the Nile, exclaimed “that Julian the apostate from Christianity was dead;” and his death was found to have occurred at that moment, in Persia: and so he emulated Apollonius Tyanæus in declaring the death of Domitian. The fate of the last of the name is somewhat peculiar: he lived at the era of the reformation of the Greek church, begun by Leo: he adhered rigidly to the worship of images, which was then proscribed, and carried them off whenever the Iconoclasts attempted to deface or destroy them. Certain Iambics were composed, in which the practice was declared superstitious and impious, and every person detected in it was seized, and a mark set upon him like Cain. The lines were indelibly inscribed on the person by puncturing them on the skin. In this way St. Theodore was stigmatized; the denunciation was tatooed on his forehead, and thence he obtained the name of Graft, or “the inscribed.” He is held in great estimation by the Latin church, as a martyr to orthodoxy; but is of no repute in the Greek, which still professes a horror at image-worship.

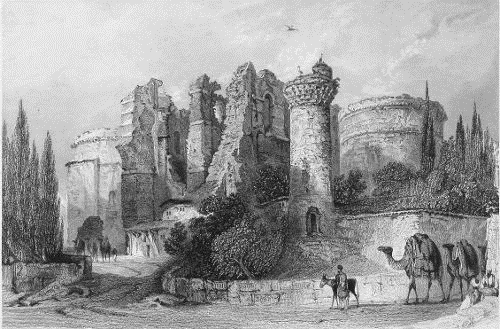

The present church of St. Theodore at Pergamus, is a poor, mean edifice, forming a strong contrast with the noble remains of the church of St. John, beside it: yet it is the only place of Christian worship now in the city. It stands on the side of the hill of the Acropolis, and appears but the remnant of a former church. The sanctuary is the only part not altogether dilapidated, the rest being only a mud-built heap. The screen, which in all Greek churches, however humble, glitters with gilding and gaudy paint, is here so dark and dingy, that even in the glow of the sun, or the ever-lighted lamps, the figures are scarcely discernible; yet it is pleasing to find, even in this dim temple, a spark of Christianity is cherished, likely to beam into a clearer light. The poor papas of the church have formed a school under the roof, in which more than thirty children are instructed, and the bibles of the British and Foreign Society are introduced.

Among the objects presented in our illustration, is one characteristic of the saint to whom the church is dedicated. The expulsion of devils was included among the miracles performed in the name of Theodore; and in our illustration is a poor maniac waiting before the sanctuary, for the purpose, while the appointed papas are exorcising him. A belief in actual possession by evil spirits, is the dogma of the Greek church at the present day; and in many of them are seen chains and manacles passed through rings in the floor, where the unfortunate maniac is bound night and day while the process of exorcism is being gone through. In a Greek monastery on the islands, is a chapel famed for the efficacy of its prayers in this way, to which patients are sent from Constantinople, and the floor of the church, at times, was almost covered with those demoniacs chained down to the ground. During the excitement of the Greek insurrection, the priests were the particular objects of Turkish persecution; and the Caloyers of this convent were particularly proscribed. They all escaped but one, and he was anxiously preparing to fly, expecting every moment his executioners; he saw them ascending the hill, on the summit of which the convent is situated, and, as a forlorn hope, he ran into the chapel, thrust his legs and arms into the fetters, and appeared violently possessed, so that no man “could bind him, no, not with chains.” The Turks entertain great respect for maniacs, whom they believe to be, when bereft of reason, in the immediate care of Allah; so they only looked compassionately on the poor man, and left the church. The Caloyer escaped, descended in the dark into a caïque, which was secretly waiting for him, and escaped finally to Russia, the great refuge of the proscribed Greeks.

APARTMENT IN THE PALACE OF EYOUB, THE RESIDENCE OF THE ASMÉ SULTANA

T. Allom. T. A. Friar.

In the delightful region of Eyoub, not far from the tomb of the Ansar, and close upon the waters of the Golden Horn, is an imperial residence recalling the memory of the unfortunate Selim, who selected this quiet and delicious retreat for his sister, to which he might occasionally retire in pursuit of that tranquillity his gentle spirit was not doomed to enjoy, among the perils and tumults that disturbed his reign. It bears the impress of his hand. Though inclining to and beginning to adopt European usages, his taste was still Oriental. Unlike the bold and uncompromising character of Mahmoud, he halted between two opinions; and, while the new palace of the one exhibits on the shores of the Bosphorus a noble specimen of European architecture, the new palace of the other is no improvement on Eastern barbarism; the palace is perfectly Turkish.

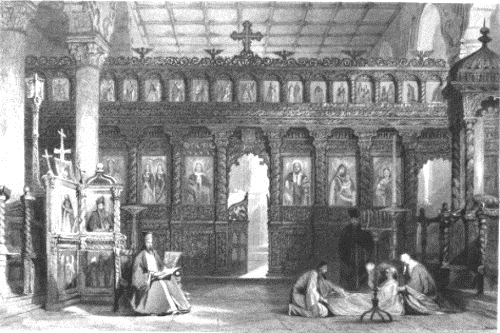

On passing along the arabesque front, the gaudy glare of the gilded apartments within are reflected through any open casement with an almost painful and dazzling lustre, particularly if the sun shines, so as to repel the gazer. The reception-room, or salaamlik, the only part given in our illustration, is remote from the harem, from whose mysterious recesses all strangers are utterly excluded: it is entered by a close curtain or screen drawn across the door, and immediately falling behind the person who passes, and gives a kind of mysterious and jealous precaution even to this permitted room. Here a balustrade of pillars runs across, leaving a passage in the centre which is ascended by steps, so that the upper end is raised like the dais of our Gothic halls. This portion of the apartment is covered over with gilding; the walls are pierced with various niches and circular recesses, ornamented with pendent members like icicles, and recall the mind to the cloistered sculpture of our old churches, and, notwithstanding the bright glare, convey the impression of gilding on a coffin. The panels are decorated with embossed festoons, glittering with burnished gold on a frosted surface. The ceiling, which in a Turkish apartment is always highly ornamented, is enclosed in an octagonal moulding with a central embossment, from which issue to the circumference radiating decorations; the ground is azure blue studded with gilded stars.

This spacious apartment, like every other room, is entirely divested of furniture. The only seats are cushions of a divan, like a sofa, running round all the walls, on which a man of elevated rank sits cross-legged, smoking a chiboque, whose long tube extends many yards on the floor below, where it is received into a gilded vase, and renovated by a kneeling attendant. Persons of inferior rank recline on carpets spread on the floor; beside the balustrade stand the mutes and black slaves, ready to do the behests of their master; and, as every person is admitted, he makes a profound salaam, nearly touching his forehead to the ground, on which he lays his hand, and then raises it to his head as if to scatter dust upon it. Such is the general description of every salaamlik, or hall of salutation, of which this imperial one is a model.

The edifice is appropriated to the Asmé Sultana, or sister of the reigning sovereign. The former tenant, for whom it was erected by Selim, was one of whom the scandalous chronicles of Pera reported many delinquencies: she was said to be of a perverse and implacable character, very different from her gentle brother; she was in the habit of fixing her affections on every one who struck her fancy, and allowed no restraint upon her will, which it was equally fatal to refuse or comply with. It was the agreeable recreation of all classes, Turks, Rayas, and Franks, to proceed either by land or water to some of the lovely valleys opening on the Bosphorus, and pic-nic on the grass; here she used to repair, and her approach among the various groups was described to be like the appearance of some bird of prey among the feeble flocks of smaller fowl. Every man trembled, lest she should fix her ominous glance on him. A dragoman of the English mission, who possessed a comely face, one day attracted her notice: a slave notified to him that a lady wished to speak with him, and he followed her, nothing loth. When arrived at where a group of Turkish women were seated, he recognized with horror the too-well-known countenance of the sultan’s sister, through the disguise with which she had covered it. After some refreshments, which were handed to him, he retired, but was followed by the slave, who intimated to him to repair, at a certain hour at night, to her palace: instead of doing so, the dragoman immediately left the city, and proceeded to Smyrna, where he concealed himself. Meantime the rage of the disappointed lady became furious: suite and pursuite were made after him by her emissaries; nor was it till another object had attracted her volatile regards, that he ventured to return to his employment; and even then he lived in considerable anxiety. Another instance occurred soon after, which justified his apprehension. A man in the humble rank of a musician, attached to a band who were occasionally sent for to play at the seraglio, attracted her notice, and was selected as the fated object of her regard; he afterwards, in some way, incurred her displeasure, and he, and the whole company to which he belonged, were sacrificed. A caïque was sent for them from the seraglio to the Princess’ Islands, where they resided, and they went as usual, without apprehension; the next day the caïque returned without them, but brought back their clothes to their distracted families; it was then learned that they had been all cut to pieces for the imputed offence of one man, and their bodies cast into the sea.

The sister of Sultan Mahmoud, the Asmé Sultana, who now possesses the palace, and occasionally visits it, is the widow of an officer of high rank, and conducts herself with discretion: she regulates her domestic affairs with strict propriety, and affords a protection to her dependents, which even her terrible brother, the sultan, dared not violate. Among the young ladies of her establishment was one who, without any high degree of personal charms, had attracted the notice of Mahmoud in one of his visits, and he immediately proposed to receive her into his harem; to his astonishment, this flattering proposal was declined by the girl. She resisted his offers, and preferred an humble attachment founded on mutual affection, to all the splendour that awaited her in the imperial seraglio. The sultan, rendered only more importunate by her opposition still persisted in his proposal, but was finally and firmly rejected; and he, whose look was death, whose nod consigned 40,000 formidable Janissaries in one day to utter annihilation, was unable to overcome the reluctance of a timid girl, and dared not violate the sanctity of that protection which the Asmé Sultana had afforded her; so she was ultimately allowed to follow the bent of her own inclination, and select a lover for herself.

REMAINS OF THE CHURCH OF ST. JOHN−PERGAMUS.

ASIA MINOR

T. Allom. J. Tingle.

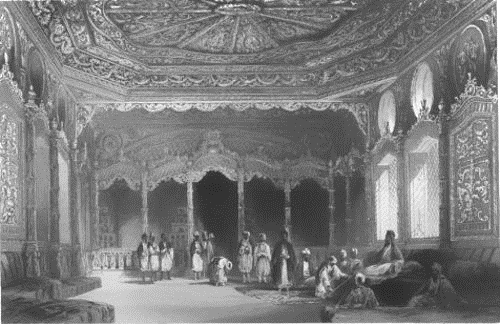

Among the first edifices, erected by Constantine the Great to Christianity, in his new city, was one dedicated to St. John the Evangelist, whom the Greeks hold in the highest veneration, and distinguish by the appellation of “The Great Theologian.” It was situated in the Hebdomum, or great plain, and was one of its most striking ornaments. In the subsequent reign of Theodosius the Great, the heart of St. John the Baptist, or, as the Greeks call him, the Prodromus, or “fore-runner” of Christ, was discovered, and the precious relic solemnly deposited in this church of his namesake by the emperor. He then directed other edifices to be built to the great theologian in the cities where his churches of the Apocalypse were founded, and one of extraordinary dimensions at Pergamus.

This church was, next to that of Santa Sophia, the best model of a Greek Christian edifice. Its remains at this day are of gigantic proportions, and afford a melancholy memorial of the vast Christian population that required so large an edifice, where now the existence of Christianity is hardly known. It stands near the great khan of the city, and rises above all the other buildings, on which it seems to look down. The length of the ruin is 225 feet, and its height about half its length. It is built of layers of Roman brick and masses of marble; and everywhere abounds in the fragments of architectural ornaments, which seem to have been drawn away from other edifices to adorn it. Two rows of granite columns still stand, dividing it into two aisles, and supporting the gallery designed for females. In the Greek church they are always separated. An Oriental feeling secludes them behind close lattices above, while men only occupy the body of the church below. The altar still stands in a semicircular recess, flanked by copolas on either side, forming a spacious area of 160 feet in circumference, crowned with domes 100 feet in height, towering far above the external walls. The doors are very lofty, fronting a spacious curve in the opposite wall, which leads to a vaulted apartment supported by a massive pillar.

The Turks entertain for the name of St. John a considerable respect and veneration. He is recognized in the Koran as the son of Zacharias, and the account of him resembles that in the Gospel. His father was promised a child, and, from the age of his wife, he doubted the fulfilment of it; as a token and punishment, he was struck dumb, and was unable to speak for three days. The Turks, who do not seem to make any distinction between the Evangelist and the Baptist, suffered this edifice to continue its Christian worship after they had overrun Asia Minor, and taken possession of this city of the Apocalypse; but on the subjugation of Constantinople, when Santa Sophia was assigned to the worship of Mahomet, this great Christian church shared its fate, and was converted into a mosque; but tradition says that a miracle caused it to be abandoned. To mark its appropriation to the Prophet, a minaret was built at one of its angles, as was done at Santa Sophia, where the muezzin ascended, and called the faithful to pray in it. In this minaret was a door which pointed to the west or setting sun, a proper orthodox aspect: when the muezzin returned next day to invite the people to morning-prayer, he could not find the door; and after an examination as to the cause of its disappearance, it was discovered that the tower had turned completely round on its base, and opposed an impenetrable wall to the entrance of the Islam priest: this was considered a plain indication of the will of Allah; so the edifice was restored to its former worship. This continued long after, till the decline and total decay of its Christian congregation; and still the semblance of it is faintly displayed. The traveller, in exploring his way through the ruins, is attracted by the light of a dim and dingy lamp, which he finds is placed before a dirty, tawdry picture of the panaya, stuck on the naked wall behind it. The poor Greek, his guide, as he passes it, first kisses it with affectionate respect, then kneels and bows his head to the ground, and offers up a short prayer to this his favourite picture. He then “goes on his way rejoicing,” but never presumes to pass without this tribute of devotion to the Virgin, though he probably knows nothing of the Evangelist to whom the church was consecrated. Other parts of the building are applied to the meanest uses; a portion of it is converted into a manufacture of coarse earthen ware, and filled with heaps of mud, and rude and barbarous pottery.