Полная версия:

Faust’s Metropolis: A History of Berlin

The Cistercians were not the only order to become powerful in the Mark Brandenburg: the Franciscans and the Dominicans were active, and the town of Angermünde grew around Franciscan monasteries which were in turn protected by the margraves of Brandenburg. Religious orders created a number of districts which still exist; in 1344, for example, the grand master of the Order of St John asked Johannes Reiche to create a settlement called Marienfelde in what is now part of Berlin; Reiche was given the estate in perpetuity on the understanding that he would govern in the name of the Church. It is a common misconception that the knights and the religious orders were intent on erasing the heathen from the land or, as one commentator put it, that they completed ‘the region’s first Holocaust’.56 There is no doubt that the first wave of conversions was often brutal but the notion that the knights ‘waged something akin to a twentieth-century war of extermination’ is inaccurate: after the regions were conquered the rulers were prepared to grant the local people generous terms to live and work on their land – it made economic sense to do so.57 This was particularly true of the Mark Brandenburg, where the Slavs were encouraged to stay and prosper as long as they converted to Christianity. Most Wends were permitted to retain their own language; indeed even Otto I had command of both the German and Slav languages. It was not uncommon for Slav and German nobles to intermarry, and families like the barons von Plotho from Kyritz can trace their ancestry back to Slavic Wendish princes while half the wives of the first sixteen marriages of Albert the Bear’s family were of Wendish descent.58 Groups of Wends also moved into separate villages or Kietze, some of which, like Spreewald, survived into the twentieth century with their culture intact.59 For Albert the main problem was not that his population was Slavic, but that it was too small. If the area was to prosper it needed settlers.

Like other nobles and religious leaders Albert the Bear sent representatives called locatores to attract people to his lands. These settlers were not all Germans; indeed many thousands came from other more crowded parts of western Europe attracted by the freedom from the restrictions of feudalism already in place there. Albert’s men went ‘to Utrecht and the places near the Rhine, especially to those who live near the ocean and suffer the force of the sea, namely the men of Holland, Zeeland and Flanders, and brought a large number of these people whom he settled in the fortesses and towns of the Slavs’.60 In his work Chronicle of the Slavs, written in the 1170s, Helmold of Bosau recorded how rulers took part in similar recruitment drives: Count Adolf II, who had conquered eastern Holstein in the 1140s, sent messengers to all the regions, ‘namely Flanders, Holland, Utrecht, Westphalia and Frisia, saying that whoever was oppressed by shortage of land to farm should come with their families and occupy this good and spacious land, which is fruitful, full of fish and meat, food for pasture’.61 The Flemish, Dutch and Franks were prized for their ability to drain the marshland, and many towns in the Mark Brandenburg owe their origins to them. The Flemish left their stamp in names like ‘Fläming’ and in village names like ‘Flemmingen’, named after the thirteenth-century bishop of Ermland, Henry Fleming of Flanders; the Danes gave their name to Dannenwalde, the Dutch named Neuholland, people from the lower Rhine settled Rheinsberg. Like those who colonized North America many centuries later the settlers were tough and hard working. They moved into woodland or swamps, cut down the forests, drained and cultivated the land, introduced the three-field system and the new heavy plough, and raised everything from fruit trees to vines to domestic animals. In the Cronical principum Saxonie Albert’s family was praised for its work in the area; having

obtained the lands of Barnim, Teltow and many others from the Lord Barnim (of Pomerania) and purchased the Ukermark up to the River Weise … They built Berlin, Strausberg, Frankfurt, New Angermünde, Stolpe, Liebenwalde, Stargard, New Brandenburg and many other places, and thus, turning the wilderness into cultivated land, they had an abundance of goods of every kind.62

It has been estimated that the Ascanians brought over 200,000 people to the Mark between 1134 and 1320 alone. It was at this time that the trade routes which had passed over the sheltered fortresses of Köpenick and Spandau shifted slightly to cross the Spree at Berlin. With this, the city was born.

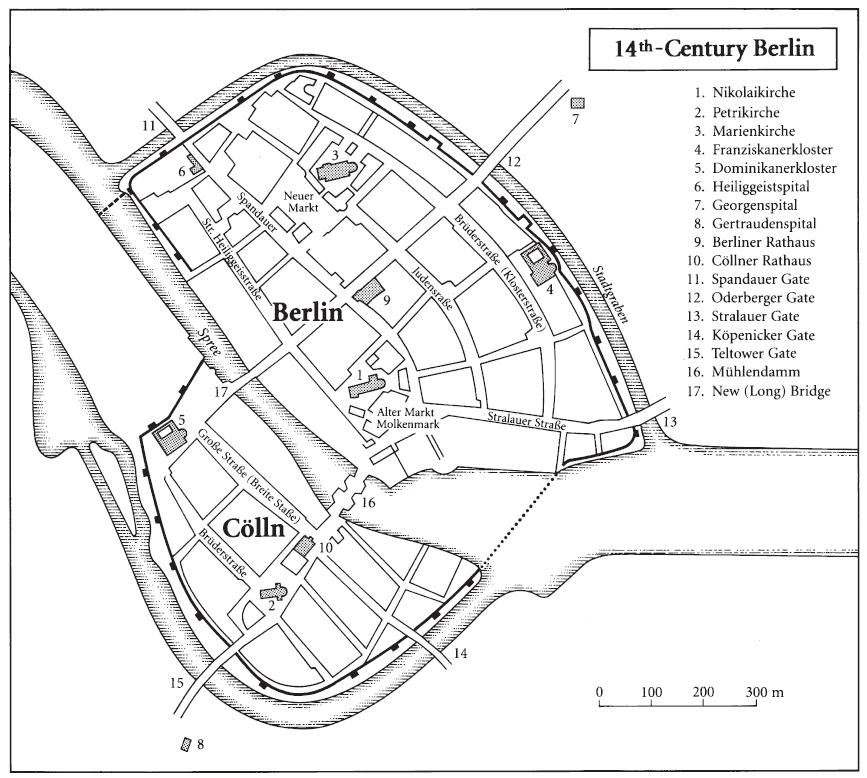

The city of Berlin was founded sometime in the late twelfth century although there is no single reliable date. The question of ‘foundation’ is itself ambiguous as the city now contains the much older settlements of Spandau, Köpenick, Lützow (Charlottenburg) and Teltow. Neither did Berlin start as a single settlement but consisted of two separate entities called Berlin and Cölln, located on opposite banks of a narrow point on the river Spree.63 Years later the East Germans would use this to try to justify the division of the city by the Wall, claiming that Berlin had ‘always’ been split in two. In reality it was not unusual to have two settlements co-existing and many towns of the Mark, including Potsdam and Brandenburg, started in this way, as did many other great European cities – Paris was originally divided into three parts, with the left bank starting as a Roman settlement; Prague began as two settlements, joined in the twelfth century by the Judith Bridge (replaced in the fourteenth century by Charles IV’s magnificent bridge); and Buda and Pest were only united a century ago.64 In historical terms the two settlements at Berlin actually joined quite early.65 But the most important factor in the prosperity of the twin town was its control of a vital crossing point on the Spree before it emptied into the river Havel, at a place where the flat and traversable Barnim and Teltow plateaux lay only five kilometres from one another.66 The Slavs would have found the position too exposed and vulnerable but by the twelfth century the region was more secure and the very lakes and marshes which had once protected the Slavic fortresses were now seen as a hindrance to the movement of goods. From its earliest years Berlin grew strong on trade.

Much has been written over the centuries to portray Berlin as a city which was somehow predestined to play a vital role first in Prussian and then in German politics. This was not the case. For centuries Berlin and Cölln remained small trading towns of minimal importance compared with dazzling contemporaries like Augsburg or Nuremberg. Berlin lay too far north to be on the great east – west route which ran along the Harz foreland and through Thuringia, and acted only as an optional stop for merchants travelling from Magdeburg and Brandenburg on their way to Frankfurt-an-der-Oder, Leubus and Kiev. The first significant change in Berlin’s fortunes came only with the increase of trade in the Baltic.67

The Germans had been trading in the Baltic before the year 1000 but it was their eastward expansion in the twelfth century which led to a dramatic increase in activity in the entire region. In 1241 an alliance was formed between Lübeck and Hamburg to protect the overland route from the Baltic to the North Sea, an agreement which formed the nucleus of the great Hanseatic League.68 By 1370 seventy-seven cities, including all significant centres in northern Europe, were members, including Cologne and Brandenburg, Riga and Braunschweig, and trade extended all the way from London to Russia. Berlin joined much later and it was first mentioned only as a nominal member in 1359. Goods were moved in wooden ships known as ‘cogs’, which often measured over sixty feet in length; by 1368 around 700 such ships were sailing out of Lübeck harbour each year. The growth of the Baltic markets also promoted north – south trade and new routes now threaded their way over the Alps to Nuremberg and from there to Berlin over Barnim and Teltow and on to the north. Berlin’s most important link was with Hamburg, with which it traded over the Spree – Havel – Elbe connection, becoming part of the route to the Oder and to the Ostsee. Important Berlin traders like Thilo von Hameln dealt in the high-quality ‘Berlin rye’ and local oak, which was shipped to Hamburg in cargo boats, while herring and dried cod moved back to Berlin from the Ostsee; iron was brought in from Thuringia; fine cloth came in from Flanders; saffron, pepper, cinnamon, ginger, figs, oil and other spices came in from the Mediterranean and the Orient; wine arrived from northern Italy, Spain, Greece and the Rhine and Mosel areas; and long-distance trade flourished in everything from rice to weapons. Local products were also important. Berlin beer became famous in Hamburg and Lübeck, and trade in honey, wax, feathers, leather, skins, wool, pitch, pewter and brass continued to grow.

By the mid thirteenth century special trade agreements criss-crossed Europe and in March 1252 King William of Holland opened up a favourable trading partnership between the Netherlands and Berlin so that many local merchants went to Ghent, Utrecht and Flemish cities, as well as to Hamburg, Lübeck, Lüneburg and Stettin. In that year Berlin citizens were granted the Landesherrlichen Zollstätten, the freedom to control tolls, while the Stendal guild gave exemption to the residents of Berlin, Brandenburg and Prenzlau from duty normally paid for most goods, including precious Flemish cloth. The new Brandenburg laws defended the rights of citizens to hold a market and ensured their personal freedom. By the end of the thirteenth century Berlin had joined the ranks of that extraordinary institution of medieval Europe – the independent town.

‘Stadt Luft macht frei’, went the old German expression: ‘city air makes one free’. By the thirteenth century small self-governing walled communities were flourishing throughout Europe, separated from the oppressive world of feudalism which dominated life outside. When you entered the gates of the town you passed from the immediate jurisdiction of the prince or king or bishop who controlled the territory into an independent community; you might be a serf or a knight but if you resided in the town for a year and a day you automatically became a free citizen. Townspeople had their own markets and councils, and in the centre one found not a palace but a market square and a town hall. The powerful medieval guilds controlled everything from prices to the quality of goods, from the number of employees in a given business to the accepted working hours, and inspectors regularly combed towns like Berlin ensuring that craftsmen did not advertise their products or undercut fellow producers or deal in foreign goods except during one of the great trade fairs which were held throughout Europe. The proud seals of shoemakers and goldsmiths and tailors also concealed harsh regulations and petty restrictions like the Beeskow Law which dictated that only Germans could be members of a guild, and there were fines for disobeying guild restrictions, fines for wearing incorrect clothing, fines for selling goods on the incorrect day and fines for usury.

The rules were tolerated because they were made and enforced by the townspeople themselves; kings and bishops allowed these freedoms because they benefited from the wealth generated by the towns.69 With prosperity came the creation of their own dynasties and although Berlin had nothing to compare with the great patrician families of Europe like the Fuggers or the Medici some, like the Blankenfeldes, the Rathenows and the Rykes (Reiches), became extremely powerful in their own right.70 Many founded new districts for themselves: the Reiche family created Rosenfelde (now Friedrichsfelde), Steglitz is named after the knight who first lived there, and many streets and surrounding villages still bear the names of their founding families. Increased patrician control was summed up in a document written on 10 April 1288 by Nikolaus von Lietzen, Johann von Blankenfelde and other leaders, in which Berlin cloth cutters were granted the right to create a guild as long as they obeyed the strict laws enforced by the dignitaries of the town – Berlin offered citizens protection and the chance to make money in return for obedience.71 The fortunate citizens of Berlin were indeed ‘free’ when compared to the poor peasants forced to eke out an existence on the land outside its walls.

The increase in wealth brought a flurry of building to the town, with the first important permanent structures being churches. The ruins of two early thirteenth-century Romanesque basilicas still lie under the foundations of the St Nikolai and St Petri churches along with more than ninety early Christian graves, but the earliest church to survive was St Nikolai. Started in 1230, with walls of simple round grey fieldstones, it was rebuilt as a late-Gothic hall church. The church of St Petri was founded around 1250; the Marienkirche and the nearby Neuen Markt were started around 1270 and rebuilt after the great fire of 1380. The religious orders were central to the creation of the city: the Franciscan monks were established in the city in 1250, the Dominican monastery was founded in 1297 on the site now occupied by the grandiose Dom, while the Knights Templars set up their cloister south of Cölln, giving their name to Tempelhof. The religious orders brought the first hospitals to Berlin: the Heliggeistspital at the Spandau Gate was built in 1250 and the Georgenspital Leper House was placed outside the Oderberg Gate, now at the edge of present-day Alexanderplatz. The first Berlin wall of fieldstones piled two metres thick was started in 1247 and it was cut through by the Stralau, Oderberg, Spandau, Teltow and Köpenick gates.

In 1256 Berlin and Cölln were linked by a mill dam which could control the flow of water, making it a more convenient river crossing and providing power for a public mill; in 1307 the two towns merged in a formal union and a new Rathaus was built on the Lange Brücke – or long bridge – so that the representatives were actually suspended between the two settlements as they sat in council. The margrave of Brandenburg did not move to Berlin, preferring to stay in the much more luxurious Spandau Castle, but he was represented there by a governor known as the Schultheiss, first appointed in 1247.72 (The name Schultheiss was given to one of Berlin’s famous brands of beer.) The towns were given their own seals; the earliest dates from 14 July 1253 and was produced under the joint authority of the Brandenburg margraves Johann I and Otto III. It depicts the Cölln eagle framed by a great city gate complete with three towers. The Sekretsiegel, the second Berlin seal to depict a bear, dates from 1338 and shows a rather ferocious beast, all claws out, striding across the landscape and dragging behind him a small Cölln eagle attached to his neck by a leash. In 1369 Berlin Margrave Otto granted Berlin the right to mint coins which were to be honoured by the people of ‘Berlin, Cölln, Frankfurt, Spandau, Bernau, Eberswalde’ and others, in effect making Berlin the financial centre of the Mark Brandenburg.73

Despite such successes Berlin was far from becoming a great city; indeed in comparison to the rest of Europe all the towns of the Mark were backward and primitive.74 The few churches in Berlin were small and unimaginative. There was no great representative architecture of the age and certainly nothing remotely like the magnificent Notre Dame, Westminster Abbey, St Stephen’s in Vienna, the Charles Bridge in Prague, or Magdeburg Cathedral; nor were there beautifully constructed city walls or ornate public buildings. Fourteenth-century Berlin-Cölln covered a modest seventy hectares and contained around 1,000 houses at a time when Paris, Venice, Florence and Genoa contained around 80,000 people and London already had 35,000, making it the largest city in England.75 Berlin could not compete with the great textile cities of Arras and Ghent or with ports like Bruges or Genoa and it lagged far behind in everything from financial acumen to the development of art and culture. Then, on 14 August 1319 the Margrave Woldemar died, bringing the end of the Ascanian dynasty which had governed the Mark Brandenburg from the time of Albert the Bear. Berlin had lost its powerful patrons.

There was no natural heir or successor to the titles held by the family of Albert the Bear, and the vast property passed into the hands of margraves from the houses of Wittelsbach and Luxembourg. Unlike the Ascanians these families had no interest in supporting the strange territory; on the contrary, they were eager to extract wealth to finance their estates elsewhere and increased taxes and fines accordingly. With no protection the Mark was soon targeted by marauding armies and bandits. Polish and Lithuanian troops raided in the 1330s, and in 1349 the Danish king Woldemar – the ‘False Woldemar’ – returned from the Crusades claiming to be Albert the Bear’s long-lost ancestor. When he was denied his ‘inheritance’ he attacked the Mark, burning dozens of villages in the ensuing struggle.

This was not the only disaster to befall the fledgling city. In 1348 the Black Death made its fearsome way through Europe and reached the Mark the following year. Suddenly people began to develop black sores on the palms of their hands or under their armpits, only to die in agony a few days later. One tenth of the population of Berlin succumbed to the bubonic plague and more fell to influenza, smallpox and typhus. Tragically, the Black Death brought the first pogroms to Berlin. The Jews had long played an important part in the region; not only had they traded there throughout the Slavic period but the first Jewish grave dates from 1244 and the Berlin Jewish community was officially founded in 1295, after which Jews and Italians largely controlled the functions of banking and money-lending. This long history did not prevent persecution and after the outbreak of plague Berliners began to blame the Jews for poisoning the wells. There were wild outpourings of hatred, Jews were viciously attacked on the streets and in their homes, and many moved for a time to a protected alley near the present Klosterstrasse which was closed off at night by a huge iron gate. Jews were put on trial and publicly executed for their ‘crimes’. Such violence was by no means unique to Berlin; over 300 Jewish communities were destroyed in western Europe and many fled east, particularly to more tolerant Poland, where they formed the largest community in Europe until the Second World War.76 This first wave of Berlin anti-Semitism ended only on 6 July 1354, when the margrave re-established the right of Jews to reside in the city and founded a Jewish school and a synagogue.

The misery of the century was not yet over. In 1376 Berlin was ravaged by another of those demons of medieval Europe – fire. It struck again in 1380 in the ‘Great Fire’, which destroyed most of the city. All the churches were levelled and the Rathaus was reduced to ashes along with all early documents and records of the city’s history, one of the reasons we know so little about Berlin’s earliest years. A contemporary chronicler reported that only six buildings were left standing, and when it was all over an unfortunate and probably blameless knight, Erich von Falke, was accused of arson and tortured to death; his head was stuck high on the Oderberg Gate.

The era was for many Berliners a miserable time of superstition and punishment. The city enforced strict penalties for the most petty crimes and, according to the Berliner Stadtbuch, women caught stealing from the Church were buried alive while those caught committing adultery were killed by the sword. Crimes like alleged poisoning, witchcraft and the use of black magic were considered serious offences and between the years 1391 and 1448, in a population of no more than 8,000 people, 121 ‘criminals’ were imprisoned, forty-six were hanged, twenty were burned at the stake, twenty-two were beheaded, eleven were broken on the wheel, seventeen were buried alive (of which nine were women), and thirteen died through other forms of torture.77 Being broken on the wheel meant just that: the victim was tied on the ground and large wooden blocks placed under him. He was then battered until his arms, legs and spine were cracked so that his broken body could be threaded on to the spokes of a specially made wheel, which was then raised on a high post and the man left to die (the wheel was not used to punish women, who were typically drowned or boiled, burned or buried alive). The corpses of the executed were hoisted up and displayed on the Lange Brücke, their bodies left to decay and their bones put out to rattle in the wind as a warning to others.78 Many other punishments are recorded on the bloody pages of the Berliner Stadtbuch – Christians who ‘mixed poison’ were burned, liars were boiled alive in a gigantic iron cauldron, and lesser charges could result in anything from having the eyes pushed out, the ears sliced through, the right hand chopped off, the tongue removed with pliers, or molten iron pushed between the teeth.79 These ‘minor’ sentences were carried out twice a week, on Mondays and Saturdays, although the public executions took place only once every two weeks – on every second Wednesday – in front of the Oderberg Gate. Such tortures were common throughout Europe but Berlin was already proving itself to be rather a violent place.

Things were to get worse. The fire which had resulted in the execution of Erich von Falke had been so destructive that Margrave Sigismund had allowed Berlin to forgo paying taxes for a year, but even so it was dangerously weak, and from the 1390s the infamous Raub Ritter – the Robber Barons from Mecklenburg and Pomerania – began to ravage the area. The very mention of their names – Quitzow, Putlitz, Bredow, Kracht – was enough to send fear through the population. These destructive, barbaric men brought catastrophe in their wake and made the decade from 1401–10 the most turbulent in the history of medieval Berlin.

The robber barons were adventurers who terrorized the area, burning and looting and raping at will. An extraordinary letter sent to the people of Lichtenberg still survives in which Dietrich von Quitzow explains that ‘if they do not send their wagons to Bötzow and bring me wood and ten Schock [a group of sixty] of good Bohemian Groschen for delivery which your Councillors of Berlin-Köpenick have captured from me, I will take everything that you possess. Thereupon I await your answer.’ Towns like Berlin, Rathenow, Spandau, Bernau, Frankfurt, Beelitz and Potsdam desperately joined together in an attempt to defend themselves, but without money or arms there was little they could do. A contemporary woodcut entitled The Storming of a Fortress by the Robber Barons shows their technique for taking heavily fortified towns: in this case some hide behind baskets filled with stones, some run forward with ladders while some stand poised to skewer the defenders of the city gate with their long pikes.80 Some documents hint at the decimation caused by the bands: in 1402 the leaders of Berlin-Cölln complained to Margrave Jobst that the Count von Lindow and the Quitzows had ‘burned and destroyed 22 villages in a week’ and that they were still plundering and burning ‘day and night’ in Barnim. In the nineteenth century the robber barons were turned into Romantic figures, and the 1888 four-act play Die Quitzows by Ernst von Wildenbruch became one of the greatest ever triumphs at the Berlin Opera House. In reality, however, the fierce bandits brought nothing but misery to the beleaguered residents of Berlin.

The fight over the succession of the Mark Brandenburg led to years of chaos during which Berlin fell into serious decline. The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse – famine, war, plague and omnipresent death – became the dominant symbol of the age and the once prosperous countryside, which had been dotted with little towns and villages, declined to almost nothing. The people of the region now believed that St John’s visionary prophecies were coming true and that the world was doomed, and the horrific paintings and woodcuts of the period, like the terrifying Dance of Death frieze in the Berlin Marienkirche, reveal the obsession with violence and decay.81 It was in part because of this unending chaos that on 8 July 1411 the Holy Roman Emperor Sigismund decided to give the troublesome land to a new leader, the descendant of the wealthy burgrave of Nuremberg. It was he who would set Berlin on the road from backward medieval trading town to one of the most important cities in Europe. His name was Frederick von Hohenzollern, and his family would rule over Berlin for over 500 years.