Полная версия:

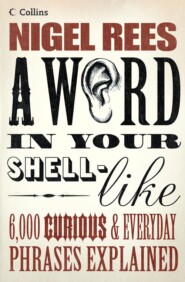

A Word In Your Shell-Like

as right as ninepence Very right, proper, correct, in order. But why ninepence? Once again, the lure of alliteration lead to the (probably) earlier phrase ‘as nice as ninepence’, and then the slightly less happy phrase resulted when someone was coining an ‘as right as’ comparison. In any case, the word ‘ninepence’ occurs in a number of proverbial phrases (‘as like as nine pence to nothing’, ‘as neat as ninepence’), dating from the time when this was a more substantial amount of money than it now is.

as seen on TV A line used in print advertising to underline a connection with products already shown in TV commercials. Presumably of American origin and dating from the 1940s/50s. Now also used to promote almost anything – books, people – that has ever had the slightest TV exposure. From Joyce Grenfell Requests the Pleasure (1976): ‘There was sponge cake of the most satisfactory consistency. Unlike the bready stuff that passes for sponge cake today (machine-made, packaged to be stirred up, as seen on TV)…’

as sure as eggs is eggs Absolutely certain. A New Dictionary of the Terms Ancient and Modern of the Canting Crew by ‘B.E.’ has ‘As sure as eggs be eggs’ in 1699. There is no very obvious reason why eggs should be ‘sure’, unless the saying is a corruption of the mathematician or logician’s ‘x is x’. But by the 18th century, the saying was being shortened to ‘as sure as eggs’, which might dispose of that theory. Known by 1680. It occurs also in Charles Dickens, The Pickwick Papers, Chap.43 (1836–7). Compare the rather different like as one egg to another (i.e. very like) which dates from Plautus in Latin but can be found in English forms from 1542. Shakespeare, The Winter’s Tale, I.ii.129 (1611) has: ‘Yet they say we are / Almost as like as eggs.’

as sure as I’m riding this bicycle A rather meaningless assertion of certainty or truth, not to be taken too seriously. Michael Flanders says, ‘Absolutely true, as sure as I’m riding this bicycle’, in his explanation following the song ‘Commonwealth Fair’ on the record album Tried By the Centre Court (1977). This was obviously a questionable assertion as he was sitting in his wheel-chair at the time. Similar expressions, to be believed or not, include ‘True as I’m strangling this ferret’ in BBC radio’s I’m Sorry I’ll Read That Again (1960s), ‘as true as the gospel’ (earliest citation 1873), ‘as true as I live’ (1640), ‘as true as steel/velvet’ (1607).

(the) Assyrian came down like a wolf on the fold An allusion to Byron’s line, ‘The Assyrian came down like the wolf on the fold’ from ‘The Destruction of Sennacherib’, St. 1 (1815). Byron based his poem on 2 Chronicles 32 and 2 Kings 19, in which Sennacherib, King of Assyria, gets his comeuppance for besieging Jerusalem in this manner.

as the art mistress said to the gardener! Monica (Beryl Reid), the posh schoolgirl friend of Archie Andrews in the BBC radio show, Educating Archie (1950–60), used this as an alternative to the traditional:

as the Bishop said to the actress (or vice versa)! A device for turning a perfectly innocent preceding remark into a double entendre (e.g. ‘I’ve never seen a female “Bottom”…as the Bishop said to the actress’). The phrase was established by 1930 when Leslie Charteris used it no fewer than five times in Enter the Saint, including: ‘“I should be charmed to oblige you – as the actress said to the bishop,” replied the Saint’; ‘“There’s something I particularly want to do to-night.” “As the bishop said to the actress,” murmured the girl’; and, ‘“You’re getting on – as the actress said to the bishop,” he murmured.’

as the crow flies The shortest distance between two points. Known by 1800. In fact, crows seldom fly in a straight line but the point of the expression is to express how any bird might fly without having to follow the wanderings of a road (as an earthbound traveller would have to do).

as the monkey said…Introductory phrase to a form of Wellerism. For example, if a child says it can’t wait for something, the parent says: ‘Well, as the monkey said when the train ran over its tail, “It won’t be long now”.’ According to Partridge/Slang, there is any number of ‘as the monkey said’ remarks in which there is always a simple pun at stake: e.g. ‘“They’re off!” shrieked the monkey, as he slid down the razor blade.’

as the poet has it/says A quoter’s phrase, exhibiting either a knowing vagueness or actual ignorance. ‘As the poet says’ was being used in 1608. This is in a letter from the poet Thomas Moore to Lady Donegal in 1813: ‘I was (as the poet says) as pleased as Punch.’ When Margaret Thatcher was British Prime Minister, she was interviewed on radio (7 March 1982) about how she felt when her son, Mark, was believed lost on the Trans-Sahara car rally. She realized then, she said, that all the little things people worried about really were not worth it…‘As the poet said, “One clear morn is boon enough for being born,” and so it is.’ (In this case, she might be forgiven for using the phrase, as the authorship of the poem is not known.) The phrase can also be used to dignify an undistinguished quotation (rather as PARDON MY FRENCH excuses swearing): P. G. Wodehouse, Mike (1909): ‘As the poet has it, “Pleasure is pleasure, and biz is biz”.’

as the saying is Boniface, the landlord in George Farquhar’s play The Beaux’ Stratagem (1707), has a curious verbal mannerism. After almost every phrase, he adds, ‘As the saying is…’, but this was in itself a well-established phrase even then. In 1548, Hugh Latimer in The Sermon on the Ploughers had: ‘And I fear me this land is not yet ripe to be ploughed. For as the saying is: it lacketh weathering.’ Nowadays, ‘as the saying goes’ seems to be preferred. From R. L. Stevenson, Treasure Island, Chap. 4 (1883): ‘There were moments when, as the saying goes, I jumped in my skin for terror.’ Stevenson also uses ‘as the saying is’, however. Another, less common, form occurs in Mervyn Jones, John and Mary, Chap. 1 (1966): ‘She gave herself, as the phrase goes. It wouldn’t normally be said that I gave myself: I took her, as the phrase goes.’

as thick as two short planks Very thick (or stupid) indeed. Of course, the length of the planks is not material here, but never mind. OED2’s sole mention of the phrase dates only from 1987. Partridge/Slang dates the expression from 1950.

as though there were no tomorrow Meaning, ‘recklessly, with no regard to the future’ or ‘with desperate vigour’ (especially the spending of money), as Paul Beale glosses it in his revision of Partridge/Slang, suggesting that it was adopted from the USA in the late 1970s. However, it had been known since 1862. ‘The free travel scheme aimed at encouraging cyclists to use trains unearthed a biking underground which took to the trains like there was no tomorrow’ – Time Out (4 January 1980); ‘The evidence from the last major redrawing of council boundaries is mixed. Some authorities did go for broke, and spent their capital reserves as though there were no tomorrow’ – The Times (9 June 1994).

astonish me! A cultured variant of the more popular amaze me! or surprise me! inserted into conversation, for example, when the other speaker has just said something like, ‘I don’t know whether you will approve of what I’ve done…’ In some cases, an allusion to the remark made by Serge Diaghilev, the Russian ballet impresario, to Jean Cocteau, the French writer and designer, in Paris in 1912. Cocteau had complained to Diaghilev that he was not getting enough encouragement and the Russian exhorted him with the words, ‘Étonne-moi! I’ll wait for you to astound me’ – recorded in Cocteau’s Journals (1956).

as we know it ‘Politics as we know it will never be the same again’ – Private Eye (4 December 1981). This simple intensifier has long been with us, however. From Grove’s Dictionary of Music (1883): ‘The Song as we know it in his [Schubert’s] hands…such songs were his and his alone.’ From a David Frost/Peter Cook sketch on sport clichés (BBC TV, That Was the Week That Was, 1962–3 series): ‘The ghastly war which was to bring an end to organised athletics as we knew it.’

as we say in the trade A slightly self-conscious (even camp) tag after the speaker has uttered a piece of jargon or something unusually grandiloquent. First noticed in the 1960s and probably of American origin. From the record album Snagglepuss Tells the Story of the Wizard of Oz (1966): ‘“Once upon a time”, as we say in the trade…’ Compare the older as we say in France, after slipping a French phrase into English speech (from the 19th century) – and compare THAT’S YOUR ACTUAL FRENCH.

as you may know…or as you may not know See GOD, WHAT A BEAUTY.

at a stroke Although this expression for ‘with a single blow, all at once’ can be traced back to Chaucer, the allusion latterly has been to the supposed words of Edward Heath, in the run-up to the British General Election of 1970. ‘This would, at a stroke, reduce the rise in prices, increase productivity and reduce unemployment’ are words contained in a press release (No. G.E. 228), from Conservative Central Office, dated 16 June 1970, that was concerned with tax cuts and a freeze on prices by nationalized industries. The perceived promise of ‘at a stroke’, though never actually spoken by Heath, came to haunt him when he became Prime Minister two days later.

at daggers drawn Meaning, ‘hostile to each other’. Formerly, ‘at daggers’ drawing’ – when quarrels were settled by fights with daggers. Known by 1668 but common only from the 19th century. ‘Three ladies…talked of for his second wife, all at daggers drawn with each other’ – Maria Edgeworth, Castle Rackrent (1801). ‘It just might be different this time, however, because of a dimension that, amid all the nuclear brouhaha, has received much less attention than it merits. The two Korean governments may be at daggers drawn, but this has not stopped their companies from doing business’ – The Independent (28 June 1994); ‘The trick will be shown on The Andrew Newton Hypnotic Experience which starts on BSkyB next Friday and will have fellow illusionist Paul McKenna glued to his seat – the pair have been at daggers drawn for years’ – Today (8 October 1994).

(the) Athens of the North Nickname for Edinburgh, presumably earned by the city because of its reputation as a seat of learning. It has many long-established educational institutions and a university founded in 1583. In addition, when the ‘New Town’ was constructed in the early 1800s, the city took on a fine classical aspect. As such, it might remind spectators of the Greek capital with its ancient reputation for scholastic and artistic achievement. Calling the Scottish capital either ‘Athens of the North’ or ‘Modern Athens’ seems always to have occasioned some slight unease. James Hannay, writing ‘On Edinburgh’ (circa 1860), said: ‘Pompous the boast, and yet a truth it speaks: / A Modern Athens – fit for modern Greeks.’ Most such phrases date from the 19th century, though this kind of comparison has now become the prerogative of travel writers and journalists. Paris has been called the ‘Athens of Europe’, Belfast the ‘Athens of Ireland’, Boston, Mass., the ‘Athens of the New World’, and Cordoba, Spain, the ‘Athens of the West’. In one of James A. Fitzpatrick’s ‘Traveltalks’ – a supporting feature of cinema programmes from 1925 onwards – the commentator said: ‘And as the midnight sun lingers on the skyline of the city, we most reluctantly say farewell to Stockholm, Venice of the North…’ From Tom Stoppard’s play Jumpers (1972): ‘McFee’s dead…he took offence at my description of Edinburgh as the Reykjavik of the South.’ ‘All those colorful canals, criss-crossing the city, that had made travel agents abroad burble about Bangkok as the Venice of the East’ – National Geographic Magazine (July 1967); ‘Vallam is a religious spot, once known as the Mount Athos of the North’ – Duncan Fallowell, One Hot Summer in St Petersburg (1994).

at one fell swoop In a single movement or action, all at once. A Shakespearean coinage. In Macbeth (IV.iii.219), Macduff is reacting to being told of the deaths of his wife and all his children: ‘Did you say all? – O Hell-kite! – All? / What, all my pretty chickens, and their dam, / At one fell swoop?’ So the image is that of a kite swooping on its prey. ‘Fell’ here means ‘fierce, ruthless’.

at one with the universe Meaning, ‘in harmony with the rest of mankind’ or, at least, ‘in touch with what is going on in some larger sphere’. When the Quaker George Fox (1624–91) consented to take a puff from a tobacco pipe, he said no one could accuse him of ‘not being at one with the universe’. Sometimes the phrase is ‘atoneness with the universe’. Compare, from Gore Vidal, Myra Breckinridge, Chap. 13 (1968): ‘[With a hangover from gin and marijuana] I lay in that empty bathtub with the two rings, [and] looking up at the single electric light bulb, I did have the sense that I was at one with all creation.’

attention all shipping! For many years on BBC radio, the shipping (weather) forecasts were preceded by this call when rough seas were imminent. Then would follow: ‘The following Gale Warning was issued by the Meterological Office at 0600 hours GMT today…’ (or whatever).

at the crack of dawn (or day) Meaning, ‘at the break of day, dawn’, but often used jovially in the sense of unpleasantly early, as when complaining of having to get up early to carry out some task. Apparently of US origin (by 1887), ‘crack of day’ seems to have come before ‘crack of dawn’.

at the drop of a hat Originally an American expression meaning ‘at a given signal’ – when the dropping of a hat was the signal to start a fight or race. The phrase has come to mean something more like ‘without needing encouragement, without delay.’ For example, ‘He’ll sit down and write a witty song for you at the drop of a hat.’ Hence, the title of a revue At the Drop of a Hat (1957) featuring Michael Flanders and Donald Swann – who followed it up with At the Drop of Another Hat (1963).

at the end of the day This must have been a good phrase once – alluding perhaps to the end of the day’s fighting or hunting. It appeared, for example, in Donald O’Keeffe’s 1951 song, ‘At the End of the Day, I Kneel and Pray’. But it was used in epidemic quantities during the 1970s and 1980s, and was particularly beloved of British trade unionists and politicians, indeed anyone wishing to tread verbal water. It was recognized as a hackneyed phrase by 1974, at least. Anthony Howard, a journalist, interviewing some BBC bigwig in Radio Times (March 1982), asked, ‘At the end of the day one individual surely has to take responsibility, even if it has to be after the transmission has gone out?’ Patrick Bishop, writing in The Observer (4 September 1983), said: ‘Many of the participants feel at the end of the day, the effects of the affair [the abortion debate in the Irish Republic] will stretch beyond the mere question of amendment.’ And Queen Elizabeth II, opening the Barbican Centre in March 1982, also used it. But it is the Queen’s English, so perhaps she is entitled to do what she likes with it.

at the grassroots (or from the grassroots) A political cliché, used when supposedly reflecting the opinions of the ‘rank and file’ and the ‘ordinary voter’ rather than the leadership of the political parties ‘at national level’. The full phrase is ‘from the grassroots up’ and has been used to describe anything of a fundamental nature since circa 1900 and specifically in politics from circa 1912 – originally in the US. A cliché in the UK since the late 1960s. A BBC Radio programme From the Grassroots started in 1970. Katherine Moore writing to Joyce Grenfell in An Invisible Friendship (letter of 13 October 1973): ‘Talking of writing – why have roots now always got to be grass roots? And what a lot of them seem to be about.’ ‘In spite of official discouragement and some genuine disquiet at the grassroots in both parties, 21 such joint administrations have been operating in counties, districts and boroughs over the past year’ – The Guardian (10 May 1995); ‘The mood of the grassroots party, and much of Westminster too, is for an end of big government, substantial cuts in taxation, cuts in public spending, toughness on crime, immigration and social-security spending, and as little Europe as possible’ – The Guardian (10 May 1995).

at the midnight hour The ‘midnight hour’ phrase may first have occurred in the poetry of Robert Southey. Thalaba the Destroyer (written 1799–1800, published 1801), a romance set in medieval Arabia, contains (Bk 8): ‘But when the Cryer from the Minaret / Proclaims the midnight hour, / Hast thou a heart to see her?’ Charles Lamb’s friend ‘Ralph Bigod’ [John Fenwick] in his essay ‘The two Races of Men’ (1820) has: ‘How magnificent, how ideal he was; how great at the midnight hour…’ In the same year, John Keats, ‘Ode to Psyche’, has: ‘Temple thou hast none, nor / Virginchoir to make delicious moan / Upon the midnight hours’. Keats also wrote of, ‘[Sleep] embalmer of the still midnight’, and so on. Edward Lear’s poem ‘The Dong With the Luminous Nose’ (1871) has ‘at that midnight hour’. The full phrase ‘at the midnight hour’ is a quotation from the Weston & Lee song ‘With Her Head Tucked Underneath Her Arm (She Walks the Bloody Tower)’ (1934), as notably performed by Stanley Holloway. In a speech to the Indian Constituent Assembly (14 August 1947), Jawharlal Nehru said: ‘At the stroke of the midnight hour, while the world sleeps, India will awake to life and freedom.’ Wilson Pickett, the American soul singer, established the phrase ‘In the Midnight Hour’ with his hit single of that title (1965).

at the psychological moment Now rather loosely used to describe an opportune moment when something can be done or achieved. It is a mistranslation of the German phrase das psychologische Moment (which was, rather, about momentum) used by a German journalist during the 1870 siege of Paris. He was thought to be discussing the moment when the Parisians would most likely be demoralized by bombardment. With or without the idea of a mind being in a state of receptivity to some persuasion, a cliché by 1900. ‘The Prince is always in the background, and turns up at the psychological moment – to use a very hard-worked and sometimes misused phrase’ – Westminster Gazette (30 October 1897); The Psychological Moment – title of a book (1994) by Robert McCrum; ‘Indeed, some would argue that the end of hanging in 1969 was the psychological moment at which we ceased to take crime as a whole seriously, putting the liberal-humanitarian “conscience” first’ – Daily Mail (27 August 1994).

at this moment in time (or at this point in time) I.e. ‘now’. Ranks with AT THE END OF THE DAY near the top of the colloquial clichés’ poll. From its periphrastic use of five words where one would do, it would be reasonable to suspect an American origin. Picked up with vigour by British trade unionists for their ad-lib wafflings, it was already being scorned by 1971: ‘What comes across vis-à-vis the non-ambulant linguistic confrontation is a getting together of defensible media people at this moment in time. I am personally oriented towards helpless laughter at the postures of these bizarre communicators’ – letter to The Times from J. R. Barnes (2 December 1971); ‘There were five similar towers…but at this moment in time, they were only of passing interest’ – Clive Eagleton, October Plot (1974); ‘The phrase “at that point of time”…quickly became an early trademark of the whole Watergate affair’ – Atlantic Monthly (January 1975); ‘At this point in time’ was described by Eric Partridge in the preface to the 5th edition of his A Dictionary of Clichés (1978) as the ‘mentally retarded offspring’ of IN THIS DAY AND AGE. ‘The Marines, of course, had other ideas, but fortune was not favouring them at this moment in time’ – R. McGowan and J. Hands, Don’t Cry for Me, Sergeant Major (1983); ‘Thoroughly agree with you about the lowering of standards in English usage on the BBC. “At this moment of time” instead of “Now” is outrageous’ – Kenneth Williams, letter of 8 October 1976, in The Kenneth Williams Letters (1994); ‘At this point in time the private rented sector of the housing market was shrinking’ – The Irish Times (8 June 1977).

attitudes See ANGLO-SAXON.

at your throat or at your feet Either attacking you or in submissive mode. Working backwards through the citations: according to J. R. Colombo’s Popcorn in Paradise (1979), Ava Gardner said about a well-known American film critic: ‘Rex Reed is either at your feet or at your throat.’ From Marlon Brando in Playboy (January 1979): ‘Chaplin reminded me of what Churchill said about the Germans: either at your feet or at your throat.’ In fact, almost every use of the phrase tends to mention Winston Churchill. He said in a speech to the US Congress (19 May 1943): ‘The proud German Army by its sudden collapse, sudden crumbling and breaking up, has once again proved the truth of the saying “The Hun is always either at your throat or at your feet”.’ That is as far back as the phrase has been traced, though Dorothy L. Sayers, Have His Carcase, Chap. 12 (1932), has the similar: ‘Like collies – lick your boots one minute and bite you the next.’

au contraire, mon frère See EAT MY SHORTS.

August See MAKES YOUR ARMPIT.

auld lang syne Meaning, ‘long ago’ (literally, ‘old long since’). ‘Syne’ should be pronounced with an ‘s’ sound and not as ‘zyne’. In 1788, Robert Burns adapted ‘Auld Lang Syne’ from ‘an old man’s singing’. The title, first line and refrain had all appeared before as the work of other poets. Nevertheless, what Burns put together is what people should sing on New Year’s Eve. Here is the first verse and the chorus: ‘Should auld acquaintance be forgot, / And never brought to min[d]? / Should auld acquaintance be forgot, / And days of o’ lang syne. / (Chorus) For auld lang syne, my dear / For auld syne, / We’ll take a cup o’ kindness yet / For auld lang syne.’ ‘For the sake of auld lang syne’ should not be substituted at the end of verse and chorus.

aunt See AGONY; MY GIDDY.

Aunt Edna During the revolution in British drama of the 1950s, this term was called into play by the new wave of ‘angry young’ dramatists and their supporters to describe the more conservative theatregoer – the type who preferred comfortable three-act plays of the Shaftesbury Avenue kind. Ironically, the term was coined in self-defence by Terence Rattigan, one of the generation of dramatists they sought to replace. In the preface to Vol. II of his Collected Plays (1953) he had written of: ‘A nice, respectable, middle-class, middle-aged maiden lady, with time on her hands and the money to help her pass it…Let us call her Aunt Edna…Now Aunt Edna does not appreciate Kafka…She is, in short, a hopeless lowbrow…Aunt Edna is universal, and to those who may feel that all the problems of the modern theatre might be solved by her liquidation, let me add that…she is also immortal.’

Auntie/Aunty BBC (or plain Auntie/Aunty) The BBC was mocked in this way by newspaper columnists, TV critics and her own employees, most noticeably from about 1955 at the start of commercial television – the Corporation supposedly being staid, over-cautious, prim and unambitious by comparison. A BBC spokesman countered with, ‘An Auntie is often a much loved member of the family.’ The corporation assimilated the nickname to such effect that when arrangements were made to supply wine to BBC clubs in London direct from vineyards in Burgundy, it was bottled under the name Tantine. In 1979, the comedian Arthur Askey claimed that he had originated the term during the Band Waggon programme as early as the late 1930s. While quite probable, the widespread use of the nickname is more likely to have occurred at the time suggested above. Wallace Reyburn in his book Gilbert Harding – A Candid Portrayal (1978) ascribes the phrase to the 1950s’ radio and TV personality. The actor Peter Bull in I Know the Face, But… (1959) writes: ‘I would be doing my “nut” and probably my swansong for Auntie BBC.’ The politician Iain Macleod used the phrase when editing The Spectator in the 1960s. Jack de Manio, the broadcaster, entitled his memoirs To Auntie With Love (1967), and the comedian Ben Elton had a BBC TV show The Man from Auntie (1990–4).