Полная версия:

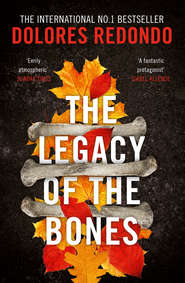

The Legacy of the Bones

‘Oh, come on, Salazar! Neither of us would be foolish enough to expose ourselves to the scrutiny of a shrink when we both know this is something he or she would be incapable of understanding. Most people would think that a cop who has nightmares about a case is at the very least stressed out or, at worst, if you push me, emotionally over-involved.’

He paused, draining the dregs of his glass then raised his arm to order another two beers. Amaia was about to protest, but the stifling New Orleans heat, the soft tones of a piano whose keys someone was stroking at the far end of the room, and an old timepiece stopped at ten o’clock which took pride of place above the bar, made her change her mind. Dupree waited until the barman had set down two fresh glasses in front of them.

‘The first few times it scares the pants off you, to the point where you think you’re starting to go crazy. But that’s not true, Salazar. On the contrary, a good homicide detective doesn’t possess a simple mind, or simple thought processes. We spend hours trying to figure out how a murderer’s mind works, how he thinks, what he wants, how he feels. Next, we go to the morgue, where we view his work, hoping the body will tell us why, because once we know the killer’s motive, we have a chance of catching him. But in the majority of cases the body isn’t enough, because a dead body is just a broken shell. For too long perhaps, criminal investigations have been more focused on understanding the mind of the criminal than that of the victim. For years, murder victims have been seen as little more than the end products of a sinister process, but at last victimology is coming into its own, showing that the choice of victim is never random, even when it’s made to appear so, that too can provide clues. In dreaming about victims, we are accessing images projected by our subconscious, but that doesn’t make them any less significant. It’s simply another form of thought-processing. For a while those apparitions of victims by my bed tormented me. I used to wake up drenched in sweat, terrified and anxious. I’d feel that way for hours, while I tried to figure out to what extent I was losing my mind. I was a rookie agent back then, partnered with a veteran. Once, during a long, tedious stakeout, I woke up suddenly in the middle of one of those nightmares. “You look like you’ve seen a ghost,” my partner said. I froze. “Maybe I did,” I replied. “So, you see ghosts too?” he said. “Well, next time you should pay more attention to what they say instead of hollering and trying to resist.” That was good advice. Over the years, I’ve learned that when I dream about a victim, part of my brain is projecting information which is already there, but which I haven’t been able to see.’

Amaia nodded slowly. ‘So, are they ghosts or projections inside the investigator’s mind?’

‘Projections, of course. Although …’

‘Although what?’

Agent Dupree didn’t reply. He raised his glass and drank.

She roused James, trying not to alarm him. He sat up in bed with a start, rubbing his eyes.

‘Is it time to go to the hospital?’

Amaia bobbed her head, her face pallid as she gave a weak smile.

James pulled on the pair of jeans and jumper that he had laid out in readiness on the end of the bed.

‘Call my aunt, will you? I promised I’d let her know.’

‘Are my parents home yet?’

‘Yes, but please don’t tell them, James. It’s two in the morning. I’m not going to give birth straight away. Besides, they probably won’t be allowed in. I don’t want them to have to sit for hours in the waiting room.’

‘So, it’s OK to tell your auntie, but not my parents?’

‘James, you know perfectly well that Aunt Engrasi won’t come here, she hasn’t left the valley in years. I promised I’d tell her when the time came, that’s all.’

Dr Villa was about fifty, with prematurely grey hair that she wore in a bob, which fell across her face whenever she leant forward. Recognising Amaia, she approached the side of her bed.

‘Well, Amaia, we have some good news and some not-so-good news.’

Amaia waited for her to continue, reaching out for James, who clasped her hand between his.

‘The good news is that you’re now in labour, the baby is fine, the umbilical cord is not wrapped round her, her heartbeat is nice and strong even during the contractions. The not-so-good news is that, despite the length of time you’ve been having contractions, your labour isn’t very advanced. There’s some dilation, but the baby isn’t properly positioned in the birth canal. What most concerns me though is that you look tired. Have you been sleeping well?’

‘No, not too well these past few days.’

This was an understatement. Since the nightmares had returned, Amaia had been sleeping on and off for a few minutes before drifting into a semiconscious state from which she would awake exhausted and irritable.

‘We’re going to keep you in, Amaia, but I don’t want you to lie down. I need you to walk – it will help the baby’s head engage. When you feel a contraction coming, try to squat; that will ease your discomfort and help you dilate.’

She gave a subdued sigh.

‘I know you’re tired,’ Dr Villa went on, ‘but it won’t be long now. This is when your daughter needs your help.’

Amaia nodded.

For the next two hours she made herself pace up and down the hospital corridor, which was empty at this hour of the morning. By her side, James seemed completely lost, distraught at how impotent he felt watching her suffer without being able to do anything.

For the first few minutes, he had kept asking if she was all right, whether he could help, or did she want him to bring her something, anything. She scarcely replied, intent upon keeping a degree of control over her body, which no longer felt like it belonged to her. This strong, healthy body that had always given her a secret feeling of pleasant self-assurance, was now no more than a mound of aching flesh. She almost laughed at the absurdity of her long-held belief that she had a high pain threshold.

In the end, James had given up and decided to remain silent. She was relieved. She had been making a superhuman effort not tell him to go to hell each time he asked her if it was hurting. Pain produced a visceral anger in her, which, coupled with her exhaustion and lack of sleep, was beginning to cloud her mind, until the only thought she could focus on was: I just want this to be over.

Dr Villa threw away her gloves, satisfied.

‘Good work, Amaia, you need to dilate a little more, but the baby is in position, so it’s all a matter of contractions and time.’

‘How long?’ she asked, anxiously.

‘As a first-time mother, it could take minutes or hours, but you can lie down now – you’ll be more comfortable. We’ll monitor you and prepare you for labour.’

The moment Amaia lay down, sleep overwhelmed her like a heavy stone slab closing eyes she could no longer keep open.

‘Amaia, Amaia, wake up.’

Opening her eyes, she saw her sister Rosaura aged ten, hair dishevelled, wearing a pink nightie.

‘It’s nearly morning, Amaia, go to bed. If Ama finds you here she’ll scold us both.’

Clumsily drawing back the blankets, Amaia placed her small five-year-old feet on the cold floor. She managed to open her eyes enough to make out the pale shape of her own bed amid the shadows, the bed she didn’t want to sleep in, because if she did, she would come in the night, to watch her with those cold black eyes, her mouth twisted in a grimace of loathing. Even without opening her eyes, Amaia could see her with absolute clarity, sensing the stifled hatred in her measured breath as she watched her feigning sleep, well aware that she was awake. Then, just when she felt herself weakening, when her muscles started to go stiff from the pent-up tension, when her tiny bladder threatened to empty its contents between her legs, eyes shut tight, she would become aware of her mother leaning slowly over her strained face, and a prayer, like an incantation, would echo in her head, over and over, preventing her even in those moments of darkest dread from falling into the temptation to disobey the command.

Don’topenyoureyesdon’topenyoureyesdon’topenyoureyesdon’topenyoureyesdon’topenyoureyes.

She wouldn’t open them, yet even with them closed she could sense the slow advance, the precision of her mother’s approach, the icy smile forming on her lips as she whispered:

‘Sleep, little bitch. Ama won’t eat you today.’

Amaia knew she wouldn’t come near if she slept with her sisters. Which was why, every night, when her parents went to bed, she would plead with her sisters, promise to do anything for them if only they would let her sleep in their bed. Flora seldom indulged her, or only in exchange for her servitude the following day, whereas Rosaura would relent when she saw Amaia cry; crying was easy when you were scared out of your wits.

She groped her way across the darkened room, vaguely aware of the outline of the bed, which seemed to recede even as the ground softened beneath her feet, and the smell of floor polish changed into a different, more pungent, earthy odour of dank forest floor. She threaded her way through the trees, protected as if by ancient columns, as she heard nearby the babbling waters of the River Baztán flowing freely. Approaching its stony banks, she whispered: the river. And her voice became an echo that bounced off the age-old rock framing the river’s path. The river, she whispered once again.

And then she saw the body. A young girl of about fifteen lay dead on the rounded pebbles of the riverbank. Eyes staring into infinity, hair spread in two perfect tresses on either side of her head, hands like claws in a parody of offering, palms turned upwards, showing the void.

‘No,’ cried Amaia.

And as she glanced about her, she saw not one but dozens of bodies ranged on either side of the river, like the macabre blossoms of some infernal spring.

‘No,’ she repeated, in a voice that was now a plea.

The hands of the corpses rose up as one, their fingers pointing at her belly.

A shudder brought her halfway back to consciousness for as long as the contraction lasted … then she was back beside the river.

The bodies were immobile again, but a strong breeze that seemed to be coming from the river itself tousled their locks, lifting them into the air like kite strings, while it whipped the limpid surface of the water into white, frothy swirls. Above the roaring wind, Amaia could hear the sobs of the little girl, who was her, mingling with others that seemed to come from the corpses. Drawing closer, she saw that this was true. The girls were weeping profusely, their tears leaving silvery tracks on their cheeks that glinted in the moonlight.

The suffering of those souls tore at her little girl’s heart.

‘There’s nothing I can do,’ she cried helplessly.

The wind suddenly died down, and the riverbed was plunged into an impossible silence. Then came a watery, rhythmic, tap-tapping.

Splash, splash, splash …

Like slow rhythmic applause from the river. Splash, splash, splash.

Like when she would run through the puddles left by the rain. After the first sounds, more followed.

Splash, splash, splash, splash, splash …

And more. Splash, splash, splash … and yet more, until it was like a hailstorm, or as if the river water were boiling.

‘There’s nothing I can do,’ she cried again, wild with fear.

‘Cleanse the river,’ shouted a voice.

‘The river.’

‘The river.’

‘The river.’ Other voices echoed.

She tried desperately to find the source of the voices clamouring from the waters.

The clouds parted over Baztán, and the silvery moonlight seeped through once more, illuminating the maidens who sat on the overhanging rocks, tapping their webbed feet on the water’s surface, long tresses swaying, their furious incantation rising from red, full-lipped mouths filled with needle-sharp teeth.

‘Cleanse the river.’

‘Cleanse the river.’

‘The river, the river, the river.’

‘Amaia, Amaia, wake up!’ The midwife’s strident voice brought her back to reality. ‘Come on, Amaia, the baby is here. Now it’s your turn.’

But Amaia couldn’t hear, for above the midwife’s voice, the maidens’ clamour still filled her ears.

‘I can’t,’ she cried.

But it was no use; they didn’t listen, only commanded.

‘Cleanse the river, cleanse the valley, wash away the crime …’ they cried, their voices merging with the cry issuing from her own throat as she felt the stabbing pain of another contraction.

‘Amaia, I need you here,’ said the midwife. ‘When the next one comes, you have to push, and depending how hard you push you can do this in two or in ten contractions. It’s up to you, two or ten.’

Amaia grasped the bars to heave herself up, while James stood behind, supporting her, silent and nervous, but reliable.

‘Excellent,’ the midwife said encouragingly. ‘Are you ready?’

Amaia nodded.

‘Right, here comes another,’ she said, her eye on the monitor. ‘Push, my dear.’

She pressed down as hard as she could, holding her breath as she felt something tear inside her.

‘It’s finished. Well done, Amaia, very good. Except that you need to breathe, for your sake and that of your baby. Next time, breathe – believe me, it’ll be over much more quickly.’

Amaia agreed obediently, while James wiped the sweat from her face.

‘Good, here comes another. Push, Amaia, let’s finish this, help your baby, bring her out.’

Two or ten, two or ten, a voice inside her head repeated.

‘Not ten,’ she whispered.

Concentrating on her breathing, she kept pushing until she felt as if her soul were draining out of her, and an overwhelming sensation of emptiness seized her entire body.

Perhaps I’m bleeding to death, she thought. And she reflected that, if she were, she wouldn’t care, because to bleed was peaceful and sweet. She had never bled like this, but Agent Dupree had nearly died from a bullet in the chest; he had told her that, although being shot was agonising, to bleed felt peaceful and sweet, like turning into oil and trickling away. And the more you bled, the less you cared.

Then she heard the wail. Strong and powerful, a genuine statement of intent.

‘Oh my goodness, what a beautiful boy!’ the nurse exclaimed.

‘And he’s blond, like you,’ added the midwife.

Amaia turned to look at James, who was as bewildered as she was.

‘A boy?’ she said.

The nurse’s voice reached them from the side of the room.

‘Yes, indeed, a boy who weighs 3.2 kilos and is pretty as a picture.’

‘But … they told us it was a girl,’ stammered Amaia.

‘Well, they were wrong. It happens occasionally, but usually the other way round, girls who look like boys because of where the umbilical cord is.’

‘Are you sure?’ insisted James, who was still supporting Amaia from behind.

Amaia felt the warmth of the tiny body the nurse had just placed on top of her, wrapped in a towel and wriggling vigorously.

‘A boy, no doubt about it,’ said the nurse, raising the towel to reveal the baby’s naked body.

Amaia was in shock.

Her son’s little face twisted in exaggerated grimaces; he was squirming as though searching for something. Raising a tiny fist to his mouth, he sucked at it hard, then half-opened his eyes and stared.

‘Oh my God, James, it’s a boy,’ she managed to say.

Her husband reached out and stroked the infant’s soft cheek with his fingers.

‘He’s beautiful, Amaia …’ he said with a catch in his voice, as he leaned over to kiss her. The tears ran down his face and his lips tasted salty.

‘Well done, my darling.’

‘Well done to you, too, Aita,’ she said, gazing at the baby, who appeared fascinated by the overhead lights, eyes wide open.

‘You really had no idea it was a boy?’ the midwife asked, surprised. ‘I was sure you did, because you kept repeating his name during the birth. Ibai, Ibai. Is that what you’re going to call him?’

‘Ibai … the river,’ whispered Amaia.

She gazed at James, who was beaming, then at her son.

‘Yes, yes!’ she declared. ‘Ibai, that’s his name.’ And then she burst out laughing.

James looked at her, grinning at her contentment.

‘Why are you laughing?’

She was giggling uncontrollably and couldn’t stop.

‘I’m … I’m imagining your mother’s face when she finds out she has to take everything back.’

2

Three months later

Amaia thought she recognised the song that reached her, scarcely a whisper, from the living room. She had just finished clearing away the lunch things, and, drying her hands on a kitchen towel, she walked over to the door, the better to hear the lullaby her aunt was singing to Ibai in a soft, soothing voice. Yes, it was the same one. Although she hadn’t heard it for years, she recognised the song her Amatxi Juanita used to sing to her when she was little. The memory brought back her adored and much-lamented Juanita, wrapped in her widow’s weeds, hair swept up in a bun, fastened with silver combs that could barely contain her unruly white curls; her grandmother, the only woman who had cradled her as an infant:

Txitxo politori

zu nere laztana,

katiatu ninduzun,

libria nintzana.

Libriak libre dira,

zu ta ni katig,

librerik oba dana,

biok dakigu. 1

Sitting in the armchair near the blazing fire, Engrasi held the tiny Ibai in her arms, eyes fixed on his little face as she recited the old verses of that mournful lullaby. She was smiling, although Amaia distinctly remembered her grandmother weeping as she sang it to her. She wondered why, reflecting that perhaps Juanita already understood the suffering in her granddaughter’s soul, and shared her fears.

Nire laztana laztango

Kalian negarrez dago,

Aren negarra gozoago da

Askoren barrea baiño. 2

When the song finished, Juanita would dry her tears with the spotless handkerchief embroidered with her initials and those of her husband, the grandfather Amaia had never known, gazing down at her from the faded portrait that presided over the dining room.

‘Why are you crying, Amatxi? Does the song make you sad?’

‘Take no notice, my love, your amatxi is a silly old woman.’

And yet she sighed, clasping the girl still more tightly in her arms, holding her a little longer, although Amaia was happy to stay.

She stood listening to the end of the lullaby, relishing the pleasure of recalling the words just before her aunt sang them. In the air lingered an aroma of stew, burning logs and the wax on Engrasi’s furniture. James had fallen asleep on the sofa, and although the room wasn’t cold, Amaia went over, covering him as best she could with a small, red rug. He opened his eyes for an instant, blew her a kiss and carried on dozing. Amaia pulled up a chair next to her aunt and sat contemplating her: the old lady had stopped singing, yet she continued to gaze in awe at the face of the sleeping child. Engrasi looked at her niece, smiling as she held the child out for her to take. Amaia kissed him gently on the head before putting him in his cot.

‘Is James asleep?’ Engrasi asked.

‘Yes, we hardly slept a wink. Ibai sometimes has cholic after a feed, especially at night, so James was up in the small hours, pacing round the house with him.’

Engrasi turned to look at James. ‘He’s a good father,’ she said.

‘The best.’

‘What about you, aren’t you tired?’

‘No, you know me. I’m fine with a few hours’ sleep.’

Engrasi seemed to reflect, her face clouding for an instant, but then she smiled once more and gestured towards the cot.

‘He’s beautiful, Amaia, the most beautiful baby I’ve ever seen, and I’m not just saying that because he’s ours; there’s something special about Ibai.’

‘You can say that again!’ declared Amaia. ‘The baby boy who was supposed to be a girl but changed his mind at the last minute.’

Engrasi pulled a serious face. ‘That’s exactly what I think happened.’

Amaia looked puzzled.

‘I did a reading when you first became pregnant – just to make sure everything was all right – and it was obvious then that the baby was a girl. Over the following months, I consulted the cards several times, but never looked into the question of the baby’s sex again because it was something I already knew. Towards the end, when you were acting strangely, saying you felt unable to choose a name for the baby or to buy her clothes, I came up with a plausible psychological explanation,’ she said with a smile, ‘but I also consulted the cards. I must confess that, for a while, I feared the worst; that this uncertainty you felt, this paralysis, was a sign that your child would never be born. Mothers sometimes have premonitions like that, and they always reflect something real. But on that occasion, no matter how many times I consulted the cards about the baby’s sex, they wouldn’t tell me – and you know what I always say about the things the cards won’t tell us: if the cards won’t tell, then we’re not meant to know. Some things will never be revealed to us, because their nature is to remain mysterious; other things will be revealed when the time is right. When James called me early that morning, the cards couldn’t have been clearer. A boy.’

‘Are you saying you think I was going to have a girl but in the last month she turned into a boy? That’s physically impossible.’

‘Yes, I think you were going to have a daughter, I think you probably will have her one day, but I also believe this wasn’t the right time for her, that someone left the decision until the last moment and then decided you’d have Ibai.’

‘And who do you think took that decision?’

‘Perhaps the same one who gave him to you.’

Amaia stood up, exasperated.

‘I’m going to make some coffee. Do you want a cup?’

Aunt Engrasi ignored the question. ‘You’re wrong to deny it was a miracle.’

‘I’m not denying it, Auntie,’ she protested, ‘it’s just that …’

‘Don’t believe in them, don’t deny their existence,’ said Engrasi, invoking the old incantation against witches that had been popular as recently as a century earlier.

‘Least of all me,’ whispered Amaia, recalling those amber eyes, the fleeting, high-pitched whistle that had guided her through the forest in the middle of the night as she struggled with the feeling of being in a dream while at the same time experiencing something real.

She remained silent until her aunt spoke again.

‘When are you going back to work?’

‘Next Monday.’

‘How do you feel about it?’

‘Well, Auntie, you know I like my job, but I have to admit that going back has never felt this hard, not after the holidays, or after our honeymoon. Everything’s different now, now there’s Ibai,’ she said, glancing at his cot. ‘It feels too soon to be leaving him.’

Engrasi nodded, smiling.

‘Did you know that in the past in Baztán women had to stay at home for a month after they gave birth? That was the period the Church deemed sufficient to ensure the baby’s health and survival. Only then was the mother allowed out to take the baby to the church to be baptised. But every law has its loophole. The women of Baztán were known for getting things done. A month was a long time, considering most of them were obliged to work, they had other children, livestock and crops to tend, cows to milk. So whenever they had to leave the house, they would send their husbands up to the roof to fetch a tile. Then they tied it tightly on their head with a scarf. That way the women were able to carry out their chores, while continuing to observe the custom, because as you know, in Baztán your roof is your home.’