Полная версия:

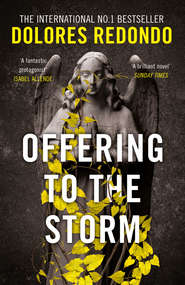

Offering to the Storm

‘Will you attend the autopsy, Inspector?’ asked San Martín, with a sweeping gesture that included Deputy Inspector Etxaide.

‘Start without me, Doctor, I’ll join you later. Perhaps you’d like to go, Jonan, there’s something I have to do first,’ she added evasively.

‘Going home again today, boss?’ he teased.

She smiled, admiring his astuteness.

‘All right, Deputy Inspector, would you like to come with me?’

13

The receptionist at the University Hospital hadn’t forgotten Amaia, judging by the way the woman’s face froze the instant she saw her. Even so, the inspector fished out her badge, prodding Jonan to do likewise. Both detectives placed their badges squarely on the counter.

‘We’d like to see Dr Sarasola, please.’

‘I don’t know if he’s here,’ the woman replied, picking up the receiver. She gave their names, listened to the reply then, with a sour expression, motioned towards the lift doors. ‘Fourth floor, they’ll show you the way.’ There was a tone of caution in the woman’s voice as she said these last words. Amaia grinned at her and winked, then started towards the lift.

Sarasola received them in his office, behind a desk heaped with papers, which he pushed aside. He stood up, accompanying them to the chairs over by the window.

‘I imagine you’re here about Dr Berasategui’s death,’ he said, as they shook hands.

Few things happened in Pamplona without Sarasola’s knowledge; even so, Amaia and Deputy Inspector Etxaide were somewhat taken aback. Noticing their expressions, he added:

‘The prison governor has family ties with Opus Dei.’

Amaia nodded.

‘So, how may I help you?’

‘Did you visit Dr Berasategui in prison?’

They knew that Sarasola had visited him. She’d asked the question to see whether he’d admit it.

‘On three separate occasions – in a purely professional capacity, I might add. As you know, I have a special interest in cases of abnormal behaviour that possess the nuance of evil.’

‘Did Dr Berasategui mention anything to you about Rosario’s escape, or what happened that night?’ asked Etxaide.

‘I’m afraid our conversations were rather technical and abstract – although fascinating, needless to say. Berasategui was an excellent clinician, which made discussing his own behaviour and actions a daunting task. He thwarted all my attempts to analyse him so that in the end I limited myself to offering him spiritual solace. In any event, nothing he might have said about Rosario or what happened that night would be of any use. One thing I do know is that you should never listen to people who have embraced evil, because they only tell lies.’

Amaia stifled a sigh, which Jonan recognised as a sign that she was becoming impatient.

‘So did you talk about Rosario, or have you lost interest in the matter?’

‘Of course, but he immediately changed the subject. Knowing what you do now, Inspector, I trust that you no longer hold me responsible for Rosario’s escape.’

‘I don’t. However, I am beginning to suspect that this is all part of a far more intricate plan, starting with Rosario’s transfer from Santa María de las Nieves and culminating in the events of that night – which weren’t your fault, either.’

Sarasola leaned forward in his chair and looked straight at Amaia.

‘I’m glad you’re beginning to understand,’ he said.

‘Oh, I understand, but I still find it difficult to believe that a man like you didn’t notice that something untoward was going on in this clinic.’

‘This isn’t my—’

‘I know, I know, it’s not your clinic, but you know perfectly well what I mean,’ she snapped.

‘And I apologised for that,’ he protested. ‘You’re right, once I became involved in the case I should have kept a closer eye on Berasategui, but in this instance I, too, am a victim.’

She always found it distasteful when someone who wasn’t dead or in hospital referred to themselves as a victim. Amaia knew only too well what it meant to be a victim, and Sarasola wasn’t one.

‘In any event, Berasategui’s suicide doesn’t add up. I visited him in prison too, and I’d have said he was more of an escape risk than a suicide risk.’

‘Suicide is a form of escape,’ Jonan broke in, ‘although it doesn’t fit his profile.’

‘I agree with Inspector Salazar,’ replied Sarasola, ‘and allow me to tell you something about behaviour profiles. They may work, even for individuals suffering from mental illness. But they are far from reliable when dealing with someone who is the embodiment of evil.’

‘That’s exactly what I mean when I talk about a premeditated plan. What would drive a man like that to take his own life?’ declared Amaia.

‘The same thing that drove him to carry out those other acts: to achieve some unknown end.’

‘Bearing that in mind, do you believe Rosario is dead, or that somehow she got away?’

‘I know no more than you. Everything points to the river having—’

‘Dr Sarasola, I was hoping we had got beyond that stage in our relationship. Why not help me instead of telling me what you think I want to hear?’ she said.

‘I believe that, besides inciting those men to commit murder, Berasategui devised a way of drawing you into the investigation by leaving your ancestors’ bones in the church at Arizkun, that for months he was working towards Rosario’s transfer from Santa María de las Nieves, and her subsequent escape from this clinic. The plan was meticulously carried out, which makes me think that he took every possible contingency into account. Rosario may be an elderly woman, but after seeing the images of her leaving the clinic with Berasategui, I …’

‘You what?’

‘I believe she’s out there, somewhere,’ he admitted.

‘But why involve me, why this provocation?’

‘I can only think that it’s connected with your mother.’

Amaia took a photograph out of her bag and passed it to him.

‘This is the inside of the cave where Berasategui and my mother were preparing to kill my son, Ibai.’

Sarasola studied the image, looked at Amaia for a few seconds, then at the photograph again.

‘Doctor, I suspect that the tarttalo killings are the grisly tip of an iceberg aimed at drawing our attention away from a far more horrible crime. Something connected to these sacrileges that would explain the clear symbolic use of bones belonging to children in my family, why they wanted to kill my son and didn’t, and, I believe, the Church’s response to a desecration, which on the face of it wasn’t all that shocking.’

Sarasola looked at them in silence, then examined the photograph once more. Amaia leaned forward, touching the priest’s forearm.

‘I need your help, please. Tell me what you see in this picture.’

‘Inspector Salazar, you’re aware that you share the name of an illustrious inquisitor. When the witch hunts reached their apogee, your ancestor, Salazar y Frías opened an investigation into the presence of evil in the Baztán Valley, which spread across the border to France. After dwelling among the population for over a year, he concluded that the practice of witchcraft was much more deeply rooted in the local culture than Christianity itself, which although firmly established, had been bastardised by the old beliefs that held sway in the area prior to the foundation of the Catholic Church. Salazar y Frías was an open-minded man, a scientist and investigator, who employed methods of inquiry and analysis similar to those you use today. Of course, many of the people questioned were undoubtedly driven to confess to such practices to avoid being tortured by the Inquisition, the mere mention of which sent them into a panic. I admire Salazar y Frías’s decision to put a stop to that insanity, but among the numerous crimes he investigated, many remained unsolved, in particular those involving the deaths of children, infants and young girls, whose bodies subsequently disappeared. Such stories appear in several statements; however, once the cruel methods of the Inquisition were abolished, all the statements taken at that time were deemed unreliable.

‘What I see in this photograph is the scene of a sacrifice, a human sacrifice, the victim of which was to be your son. Human sacrifice is a heinous practice used in witchcraft and devil worship. It was the appearance of children’s bones in the desecrations at Arizkun that raised the alarm; it is common in devil worship to use human remains, especially those of children. However, the sacrifice of a living child is considered the highest offering.’

‘I know about Salazar y Frías. I understand what you’re saying, but are you suggesting a connection between the practice of witchcraft in the seventeenth century and the desecrations in Arizkun, or what nearly happened to Ibai?’

Sarasola nodded slowly.

‘How much do you know about witches, Inspector? And I don’t mean witch doctors or faith healers, but rather the ones described by the Brothers Grimm in their fairy tales.’

Jonan leaned forward, interested.

‘I know that they’re covered in warts and dwell deep in the forest,’ said Amaia.

‘Do you know what they eat?’

‘They eat children,’ replied Jonan.

Amaia laughed.

The priest turned to her, irritated by her sarcasm.

‘Inspector,’ he cautioned, ‘stop playing games with me. Ever since you walked in here, I’ve had the impression that you know more than you’re willing to let on. This is no laughing matter; stories that become folklore after being passed down through generations usually contain a grain of truth. Perhaps witches don’t literally eat children, but they feed off the lives of innocents offered in sacrifice.’

Sarasola was shrewd enough to have figured out that, as a homicide detective, she had more reasons for asking him about this subject than those she was prepared to admit.

‘All right, so what do they get in exchange for these sacrifices?’

‘Health, life, riches …’

‘And people actually believe that? I mean now, as opposed to in the seventeenth century. They believe that by performing human sacrifices they will obtain some of these benefits?’

Sarasola sighed despairingly.

‘Inspector, if you wish to understand anything about how this works, then you must stop thinking about whether it’s logical or not, whether it corresponds to your computerised world, your profiling techniques. Stop thinking in terms of what you think a modern person would believe.’

‘I find that impossible.’

‘That’s where you are mistaken as are all those fools who base their idea of the world on what they see as logical, scientifically proven fact. Believe me, the men who condemned Galileo for suggesting that the Earth revolved around the Sun did exactly the same thing: based on their centuries-old understanding of the cosmos, they argued that the Earth was the centre of the universe. Think about this before you reply: do we know, or do we believe we know because that’s what we’ve been told? Have we ourselves tested each of the absolute laws which we accept unquestioningly because people have been repeating them to us over the centuries?’

‘The same argument could apply to the belief in the existence of God or the Devil, which the Church has upheld for centuries—’

‘Indeed, and you are right to question that, though perhaps not for the reasons you think. Find out for yourself, search for God, search for the Devil, then draw your own conclusions, but don’t judge other people’s beliefs. Millions live lives based on faith: faith in God, a spaceship that will take them to Orion, the belief that by blowing themselves to bits they will enter paradise, where honey flows from fountains and virgins attend their every need. What difference does it make? If you want to understand, you must stop thinking about whether it’s logical, and start accepting that faith is real, it has consequences in the real world, people are prepared to kill for their beliefs. Now consider the question again.’

‘Okay, why children, and what is done to them?’

‘Children under two are used in ritual sacrifices. Often they are bled to death. In some cases they are dismembered, and the body parts used. Skulls are highly prized, as are the longer bones, like the mairu-beso used in the desecrations at Arizkun. Other rituals make use of teeth, nails, hair and powdered bone made by crushing up the smaller bones. Of all the liturgical objects used in witchcraft, the bodies of small children are the most highly valued.’

‘Why children under two?’

‘Because they are in a transitional phase,’ Jonan broke in. ‘Many cultures believe that, prior to reaching that age, children move between two worlds, enabling them to see and hear what happens in both. This makes them the perfect vehicle for communicating with the spirit world, or obtaining favours.’

‘That’s correct. Children develop instinctual learning up to the age of two: standing, walking, holding objects, and other imitative behaviour. After that, they start to develop language, they cross a barrier, and their relationship with their surroundings changes. They cease to make such good vehicles, although similarly, youths of pre-pubescent age are also prized by those practising witchcraft.’

‘If someone stole a corpse for such purposes, where might they take it?’

‘Well, as a detective I imagine you’ve already worked that out: to a remote place, where they can perform their rituals without fear of being discovered. Although, I think I see where you’re going with this. You’re imagining temples, churches or other holy places. And you’d be quite right if we were talking about Satanism, whose aim is not only to worship the Devil, but also to offend God. However, witchcraft is a far more wide-ranging branch of evil than Satanism, and the two aren’t as closely related as you might think. Many creeds use human remains as vehicles for obtaining favours; for example, Voodoo, Santería, Palo and Candomblé, which summon deities as well as dead spirits. They perform their rituals in holy places as a way of desecrating them. And, of course, Arizkun is situated in the Baztán Valley, which has a long tradition of witchcraft, and of summoning Aker, the devil.’

Amaia remained silent for a few seconds, looking out of the window at the gloomy Pamplona sky to avoid the priest’s probing gaze. The two men said nothing, aware that behind Amaia’s calm appearance her brain was working hard. When she turned once more to Sarasola, her sarcasm had given way to resolve.

‘Dr Sarasola, do you know what Inguma is?’

‘Mau Mau, or Inguma. Not what, but who. In Sumerian demonology, he is known as Lamashtu, an evil spirit as old as time, one of the most terrible, cruel demons, surpassed only by Pazazu – the Sumerian name for Lucifer. Lamashtu would tear babies from their mother’s breast to feed on their flesh and drink their blood, or cause babies to die suddenly during sleep. Demons that killed babies while they slept existed in ancient cultures too: in Turkey they were known as “crushing demons”, while in Africa the name translates literally as “demon that rides on your back”. Among the Hmong people he is known as the “torturing demon”, and in the Philippines the phenomenon is known as bangungut, and the perpetrator is an old woman called Batibat. In Japan, Sudden Infant Death Syndrome is known as pokkuri. Henry Fuseli’s famous painting The Nightmare portrays a young woman asleep on a chaise longue while a hideous demon crouches on her chest. Oblivious to his presence, the woman appears to be trapped in a nightmare. The demon has many different names, but his method is always the same: he creeps into the rooms of sleeping victims at night and sits on their chests, sometimes clutching their throats, producing a terrifying feeling of suffocation. During this nightmare, they may be conscious, but unable to move or wake up. At other times Inguma places his mouth over that of the sleeper, sucking out their breath until they expire.’

‘Do you believe …?’

‘I’m a priest, Inspector, and you’re still thinking about this in the wrong way. Naturally, I’m a believer, but what matters is the power of these myths. In Rome, every morning at dawn, an Exorcism Prayer is performed. Various priests pray for the liberation of possessed souls, and afterwards they attend to people who come to them asking for help. Many are psychiatric cases, but by no means all.’

‘And yet exorcism has been shown to have a placebo effect on people who believe themselves to be possessed.’

‘Inspector, have you heard of the Hmong? They are an ethnic group that live in the mountainous regions of China, Vietnam, Laos and Thailand, and who collaborated with the Americans during the Vietnam War. When the conflict ended, their fellow countrymen condemned them, and many fled to the United States. In 1980, the Center for Disease Control in Atlanta recorded an extraordinary rise in the number of sudden deaths during sleep: two hundred and thirty Hmong men died of asphyxia in their sleep in the US, but many more were affected; survivors claimed to see an old witch crouched over them, squeezing their throats tight. Alerted to what was happening, parents began sleeping next to their sons to rouse them from these nightmares. When the attacks took place, they would shake them awake, or drag them out of bed. The most terrifying part was that, trapped in their waking dream, the boys could see the sinister old woman, feel her crooked fingers on their throats. This didn’t happen in a remote region of Thailand, but in places like New York, Boston, Chicago, Los Angeles … All over the country, every night, Hmong men suffered such attacks. Those who didn’t succumb were kept under strict surveillance in hospital, where the invisible attacks, in which the victims seemed to be strangled by some invisible creature, were witnessed and videod. Doctors were at a loss to diagnose a specific illness. The Hmong’s own shamans concluded that the demon was targeting this particular generation of Hmong because they had become distanced from their centuries-old traditions and protections. Requests to perform purification rites around the victims were mostly refused, because they involved animal sacrifice, even though in cases where permission was granted, the attacks ceased.

‘In 1917, seven hundred and twenty-two people died in their sleep in the Philippines, suffocated by Batibat, which translates literally as “the fat old woman”. And in 1959 in Japan, five hundred healthy young men died at the hands of pokkuri. It is believed that when Inguma awakens, he goes on a murderous rampage until his thirst is quenched, or until he is stopped by some other means. In the case of the Hmong people, the phenomenon that claimed the lives of two hundred and thirty healthy boys remains unsolved to this day.’ His eyes fixed on Amaia. ‘Even science could offer no explanation: autopsies were carried out, but the cause of death could not be determined.’

14

In accordance with Amaia’s orders, Dr San Martín had started the autopsy without them. When she and Etxaide approached the steel table, at the centre of a room filled with medical students, the pathologist had his back to them, and was busy weighing the internal organs on a scale. He turned, smiling when he saw them.

‘Just in time, we’re almost done. The toxicology tests show high levels of an extremely powerful sedative. We’ve identified the active ingredient, but I won’t hazard a guess as to the name of the drug. As a doctor, Berasategui would have known which one to use and how much to take. Most are injectable, but the small abrasions on the sides of the tongue suggest he took it orally.’

Amaia leaned over to examine through the magnifying glass the row of tiny blisters either side of the tongue, which San Martín was holding up for her with a pair of forceps.

‘I can smell a sweet, acidic odour,’ she remarked.

‘Yes, it’s more noticeable now. Perhaps the cologne Berasategui doused himself in masked it. A vain fellow indeed.’

Amaia examined the body as she listened to San Martín. The ‘Y’ incision started at the shoulders, travelling down the chest to the pelvis, laying bare the glistening insides, whose vivid colours had always fascinated her. On this occasion, San Martín and his team had forced open the ribcage to extract and weigh the internal organs, doubtless interested to see the effects of a powerful sedative on a healthy young male. The startlingly white ribs pointed up towards the ceiling. The denuded bones had a surreal look, like the frame of a boat, or a dead whale’s skeleton, or the long, eerie fingers of some inner creature trying to climb out of his dead body. No other surgical procedure quite resembled an autopsy; the only word that came close to describing it was wondrous. She understood the fascination it held for Ripper-type murderers, many of whom were skilled at making precise incisions at exactly the right depth to enable them to extract the organs in a particular order without damaging them.

Amaia observed the assistants and medical students, listening attentively to San Martín, as he pointed to the different sections of the liver, explaining how it had stopped functioning. By then, Berasategui was almost certainly unconscious. He had sought a dignified, painless death, but even he couldn’t avoid the procedure, which, he knew would inevitably follow. Berasategui hadn’t wanted to die, he had certainly never considered taking his own life. A narcissist like him would only have accepted suicide if he were forced to relinquish the control he exercised over others. And yet she had seen for herself how he had surmounted that obstacle in prison. He’d done what he did, against his own will, and that constituted a discrepancy, an abnormal element, which Amaia couldn’t ignore. Berasategui had wept over his own suicide like a condemned man forced to walk a green mile from which there was no return.

Turning to share her thoughts with Jonan, she saw that he was standing back, behind the students gathered around San Martín. Arms folded, he was gazing at the nightmarish vision of the wet, naked corpse splayed open on a table, ribs exposed to the air.

‘Come closer, Deputy Inspector Etxaide, I’ve been saving the stomach until last … I thought you’d be interested to see the contents, although there’s no doubt he swallowed the sedative.’

One of the assistants placed a strainer over a beaker, and then, tilting the stomach, which San Martín had clamped at one end, she emptied the viscid, yellow contents into the receptacle. The stench of vomit mixed with the tranquiliser was nauseating. Amaia looked on as Jonan retched, and the students exchanged knowing looks.

‘Here we see traces of sedative,’ said San Martín, ‘indicating that he reduced his food and liquid intake in order to absorb the drug more rapidly. The contact of the drug with the mucous membrane stimulated the production of stomach acid. It would be interesting to dissect the intestine, trachea and oesophagus to see how it affected those organs.’

The suggestion was greeted with general enthusiasm except by Amaia.

‘We’d love to stay, Doctor, but have to get back to Elizondo. If you’d be so kind as to give us the name of the sedative as soon as possible; we already know one of the guards supplied him with it, and probably also removed the empty phial. Having the name would help us find out how he got hold of it and whether he acted alone.’

Jonan was visibly relieved at the news. After saying goodbye to San Martín, he walked ahead of her towards the exit, trying not to touch anything. Amaia followed, amused at his behaviour.

‘Hold on a moment.’ San Martín handed over the reins to one of his assistants, and, tossing his gloves into a waste bin, plucked an envelope from his pigeonhole. ‘The test results of the decaying matter on the toy bear.’

Amaia’s interest quickened.

‘I thought they’d take much longer …’

‘Yes, the process was problematic because of the singular nature of the sample. Doubtless a copy will be waiting for you in Elizondo, but since you’re here …’