скачать книгу бесплатно

‘Do you like vegetables?’ asked Pearl.

‘Yes, we have lovely vegetables every day with our lunch.’

‘Lucky you!’ she said with a tinkling laugh. ‘What other foods do you like?’

‘Steak pie,’ I said. ‘And puddings and gravy … and cakes and burnt bread crusts …’

‘Well,’ she laughed again, ‘I’m glad you enjoy your food!’

Pearl chatted to me all the time and made a very good impression on me. She was quiet, gentle and very kind – I really liked her.

I saw Arnold taking a sideways look at me. He didn’t smile, but he didn’t frown either. I felt unsure of him, because he wasn’t friendly and warm like Pearl. But I was pleased somebody was taking an interest in me – and Pearl certainly was.

‘Where else shall we go?’ she asked.

‘Come and see the Japanese garden,’ I suggested, leading them round to the side of the house and through the gate in the wall.

‘Ooh! Isn’t this beautiful?’ She seemed quite excited.

I took them round to look at the little waterfalls and showed them where the toad sometimes sat, but he wasn’t there that day. I told her what I had learnt about the plants and the animals that lived there.

‘Oh, you are a clever boy!’ said Pearl with an admiring look. ‘Isn’t he, Arnold?’

But Arnold grunted and turned his head away without saying anything. It might have been a ‘yes’ sort of grunt, but maybe not.

Finally, we went a little way down the drive and I told them about our summer outings to the Clent Hills.

‘This seems like a lovely place,’ said Pearl as we walked back towards the house.

‘Yes, I love it here,’ I grinned.

‘We’ve enjoyed talking to you,’ she said, which I thought was rather odd as Arnold hadn’t said a word. ‘But I’m afraid it’s time for us to go now. Perhaps we might be able to come and see you again. Would that be all right?’

‘Yes,’ I agreed readily. Pearl seemed to be a lovely woman – I thought I’d definitely prefer to be with her than with a lot of big boys in a home full of strangers. So, off they went and I ran in, just in time to wash my hands and join my friends for tea.

That night in the dormitory, getting into bed and falling asleep to another bedtime story that I didn’t hear the end of, I didn’t give the visitors another thought. The next day, I remembered they’d been and I wondered whether I would ever see them again. I would have liked to see Pearl, but wasn’t so sure about Arnold. And I didn’t want to hasten leaving my idyllic life with my friends and all the kind staff, so when nobody told me anything, I didn’t ask.

It must have been a few days later, maybe a week, when my housemother sat me down and told me: ‘Tomorrow, your new mother and father are going to come and collect you.’

I was shocked. ‘What do you mean?’

‘Do you remember Mr and Mrs Gallear, the nice couple who came to see you last week?’

‘Yes, but nobody said anything, so I thought they didn’t like me.’

‘Well, they did like you and they want to take you home.’

‘Are they my real mother and father?’ I asked. Children in books always seemed to have mothers and fathers, so I assumed I must have too.

‘Not your birth mother and father, no, but they want to be your foster parents.’

‘I liked her, she was nice.’

‘Good. Well, they will be your foster parents – your foster mother and foster father. You will call them Mummy and Daddy.’

‘Oh.’

‘Won’t that be nice?’

‘Tomorrow?’ I asked, suddenly welling up with tears. ‘Does it have to be tomorrow?’

‘Yes,’ she said gently, giving me a cuddle when she saw how upset I was. ‘Don’t worry, they are looking forward to taking you back with them to their house, which will become your new home. They will look after you. You’re going to have your own bedroom and you will have a lovely time making lots of new friends where they live.’

I couldn’t speak for crying. My stomach went all wobbly and I just couldn’t take all this in. I suppose I didn’t want to and it all seemed so sudden – I had no time at all.

‘Can I take my cars and my spinning top?’

‘Yes, of course you can. We’ll put them in your case to take with you. I expect you will have some more toys to play with at their house, and maybe some new clothes of your own too.’ She gave me another hug.

‘Can’t I stay here a bit longer?’

‘No, little soldier, I’m afraid you can’t, but they’re not coming till after lunch tomorrow, so you can enjoy all this afternoon and tomorrow morning in the garden. Have a good run round, play with your friends and sit in your favourite tree, whatever you like. I’ll come and find you out there when I’ve gathered all your things to pack, then we can talk some more. Would you like that?’

I nodded, as more tears trickled down my cheeks.

‘Here, take my hankie.’

It was a fine summer’s day and I walked around all my favourite places, ending up on a branch of the cedar tree. How could this happen to me? I knew others had gone to foster homes before me, but I couldn’t talk to any of them to find out if they were happy there.

At bedtime I was tearful and my housemother soothed my fears as best she could.

‘What if I don’t like it there?’ I asked her.

‘You will like it,’ she reassured me. ‘It may take you a little time to settle and get used to belonging to a proper family, getting to know them better, and all their routines. You’ll soon forget all about us. You will make new friends and I expect you’ll be starting school soon. You’ll love school, you can learn all sorts of new things at school.’

She did her best to inspire me with confidence, but it didn’t really work. For once, I didn’t fall asleep before the bedtime story finished – I don’t think I was even listening. As I lay in my bed with the lights out, a shaft of waning daylight shining across my bed from a crack in the curtains, I hoped against hope that when I woke up in the morning it would all be a dream and I wouldn’t have to leave after all.

1959–71: THE CRUEL YEARS (#ulink_776472e1-0404-5195-b31e-88a589bd2437)

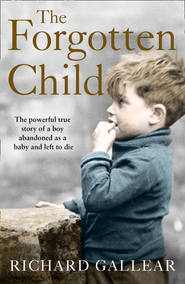

Richard at school, aged 8

CHAPTER 5

Goodbye to Happiness (#ulink_2c8b9be3-a929-577a-9590-cdbc57291454)

July 1959 (4 years, 8 months) – Fine healthy boy. Much more stable and happier. Full of imagination, conversation, knowledge of everyday things.

Richard’s last progress report before leaving Field House

30 August 1959 was a beautiful sunny day, but it didn’t feel sunny to me. It was the day my cosy world fell apart. That afternoon I would have to leave the only home I’d ever known – a happy home of fun and laughter with my friends, a secure place where every adult loved us and cared for us. I knew nothing of my beginnings, but I did know I didn’t want to leave Field House. I didn’t want to go and live anywhere else, I wanted to stay there for ever.

It was my last morning so I went to all my favourite places. First, to the vegetable garden, where I had ‘helped’ so often. Everything was growing well, including ‘my’ lettuces, poking up through the soil, and the runner beans I’d planted and watched growing up their canes.

‘I’m leaving today,’ I told the kindly gardener, trying to put on a brave face.

‘Are you now?’ he said. ‘We’ll miss you.’ He paused. ‘Have you got time to pick a few of these beans for the kitchen before you go? Then you can eat them for lunch.’

‘Yes, please,’ I said, perking up at the thought.

Next, I visited the Japanese garden and said goodbye to my friend the toad, who sat and croaked as if he understood.

The rest of the morning went far too quickly and when I went in for lunch, I was overjoyed that it was steak pie, mash and gravy with ‘my’ beans. It was all delicious, so I had another helping.

The housemother at our table told the other boys that I was leaving and they all came up to say goodbye to me as we left the dining room. I didn’t like them saying goodbye – I didn’t want to say goodbye, I didn’t want to go.

Finally, I went to my dormitory, where my housemother was packing my few belongings into a little, scuffed leather suitcase and ticking them off on a list.

‘I’ve packed some spare clothes for you,’ she explained in her kindest voice. I didn’t realise it at the time, but perhaps she didn’t want me to go either. ‘I’ve put in your favourite toys too.’

‘My cars?’ I asked.

‘Yes, both your cars and your spinning top.’

I pulled open the drawer by my bed: it was empty.

‘Where are my conkers?’ I asked, my anxiety rising.

‘In your case.’

I tried desperately to think what else I might need. Then I realised …

‘Where’s Jeffrey?’ I wailed. ‘My teddy!’ I felt under my bedcovers for him. ‘He’s not in my bed, I can’t go without him.’ I was panicking now.

‘It’s all right,’ she tried to soothe me. ‘Jeffrey is in the case too – I knew you wouldn’t want to go without him. I had to squash him in, but I think he’ll recover all right. I expect he’s a bit worried about going to a new home too.’

‘Oh, really?’ I hadn’t thought of that.

‘I’m sure we have packed everything now,’ she reassured me. ‘Let me give you a big hug.’ She put her arms round me and for those last few moments I felt secure. Would I feel like this with my new foster mother, in my new home? I had to hope so. I held on for as long as I could, then she gently pulled away.

‘Come on, it’s time to go.’

At two o’clock that afternoon, we stood on the drive, my housemother holding my hand and carrying my case in her other hand. This was a terrible moment – the phrase ‘gut-wrenching’ comes to mind when I think back to the forlorn little boy I was, standing, waiting.

‘They’ll be here in a minute or two,’ she said. ‘Now, I want you to be a good boy and be happy in your new home.’

I couldn’t say anything, so I just nodded.

‘You will have a good life and a good future with your foster parents.’

But I hardly knew them. I screwed up my eyes and hoped to vanish, but when I opened them again, I was still there.

The crunch of the gravel heralded the approach of a vehicle, which suddenly came into view and parked beside the house. I recognised it because one of the other boys had a toy version that looked the same. A small Ford van, it was hand-painted in two shades of blue. My housemother squeezed my hand and we walked across together. It wasn’t far and yet it seemed like a huge gulf of despair to me. I knew I had to try and be very brave.

Mr and Mrs Gallear both got out of the van and Pearl gave me a lovely smile and a wave. I immediately felt all right with her. If only Arnold looked happier to see me, I might have felt a bit better, but he wore the same stern, distant expression that he’d had the first time they came. I felt instinctively that he didn’t like me, which made me feel very uncomfortable. At that moment, young as I was, I knew it was Pearl who wanted me, not her husband.

‘Wave back to your foster mother,’ coaxed my housemother.

I did a little wave to her, but I felt too sad to smile.

As we walked towards them, Pearl came to meet us, wearing another flowery summer dress. She looked lovely, walking with footsteps as dainty as a dancer and beaming her happy smile at me. But standing by the van, like a dark shadow in the background, was Arnold, who was not even looking at me. Though I tried my best not to cry, I was sobbing inside. I clung to my housemother, but she gently released my grip and knelt down, with Pearl standing next to her, looking anxious.

‘Be a brave boy,’ said my housemother. ‘I won’t forget you and we will all be thinking of you, but these are your new parents and this is your new life.’ She stood again and passed my hand over to Pearl, who grasped it warmly, along with my little case.

‘There’s a list of Richard’s things in the top of the case, together with his medical notes for you to give to his new doctor.’

‘Thank you,’ said Pearl.

‘Off you go now,’ said my housemother. ‘You will be fine.’

I gave her a little wave and walked with Pearl to their van. In fact, I was focusing on it. From the little toy van one of my friends had, I knew there were only two front seats. Where would I sit? For a moment I hoped they would not have room for me and would leave me behind, but not so. Did Arnold know what I was thinking? As he walked round to the back and opened out the two rear doors my heart sank.

‘We’ve been looking forward to taking you home with us today,’ Pearl said with a smile and a squeeze of my hand. ‘We’ve put some carpet in the back of the van for you and a cushion to sit on,’ she explained. ‘To make you more comfortable.’

She gave him my case and he tossed it in the back. Now that my things were in there, I had to resign myself to going. I trusted Pearl, but I was wary of Arnold. At the time I didn’t know the word ‘vulnerable’, but that’s how I felt. I was reticent to clamber in, so Arnold lifted me up roughly and into the van, closing the doors behind me. Inside, I sat on the cushion with my legs stuck out in front. The only windows were at the front and little squares of glass in the rear doors, so I couldn’t see much either way.

Although I was fascinated by vehicles and knew that this was a Ford Thames van, I had never actually been inside any vehicle so this was all a new experience for me. Normally, I would have been excited, but not today. Arnold and Pearl got in and closed their doors. He started the engine and we were off. I had to put my hands out behind me so as not to fall off my cushion, going over the bumps.

As we went down the drive, I turned around to look through the back windows and saw Field House for the last time, receding and getting smaller as we went. Desperate to keep it in view, the tears running down my face, I craned my neck to see the building, my dormitory, the lawn, my friends and everyone I loved all disappearing for ever. Through the gates we went, round the bend and off down the drive towards the lane that led to the outside world. I was miserable – I had left behind everything I knew and loved and had no idea where they were taking me.

It was a very warm day and soon it became uncomfortably hot and airless in the back of the van. I struggled to keep my balance as we moved along the twisting country lanes. Before we had even reached the main road, my tummy started to feel like collywobbles inside and I began to feel ill – I think it must have been the upset and uncertainty.

Suddenly I was sick. I vomited all down the front of my clothes and my legs, onto the cushion, the carpet – everywhere. I started to cry in earnest now, as Arnold rammed on the brakes and Pearl turned around with a sympathetic glance.

‘I’m sorry,’ I said as Arnold pulled into the side of the road, muttering loudly. ‘Sorry,’ I repeated, ‘I didn’t mean to do it.’

But that was only the start of my troubles. As Pearl whispered soothing words, Arnold yelled, ‘You stupid child!’

He flung his door open and stomped round to the back of the van. As bad-tempered as he might be, I still thought he was going to clean me up and sort things out.

But I was wrong.

He yanked the doors open and with an angry face and staring eyes, dragged me out, down onto the ground. Then, right there on the gravel at the side of the road, he laid into me, fists flailing, blow after blow, shouting at me all the while.

‘How dare you make a mess like that, pouring out your filthy insides all over my van! You little brat!’ he shouted. ‘Haven’t they taught you how to behave?’

‘I didn’t m-m-mean it,’ I stammered. But he hit me all the harder.

I could understand why he was cross. I knew I shouldn’t have done that, but I couldn’t stop myself. Again and again he hit me, as I instinctively curled myself into a ball.