Полная версия:

The Forgotten Child: A little boy abandoned at birth. His fight for survival. A powerful true story.

Copyright

HarperElement

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published by HarperElement 2019

FIRST EDITION

Text © Richard Gallear 2019

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2019

Cover photograph © Bert Hardy/Picture Post/Getty Images (front cover archive image is not of author)

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

Richard Gallear asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Find out about HarperCollins and the environment at

www.harpercollins.co.uk/green

Source ISBN: 9780008320768

Ebook Edition © March 2019 ISBN: 9780008320775

Version: 2019-01-31

Dedication

In memory of Joseph Lester, who saved my life

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

1954: ABANDONED

Chapter 1 – Left to Die

1954–59: THE EARLY YEARS

Chapter 2 – Field House

Chapter 3 – The Monkey Man

Chapter 4 – Chosen

1959–71: THE CRUEL YEARS

Chapter 5 – Goodbye to Happiness

Chapter 6 – The House of Dangers

Chapter 7 – One Day at a Time

Chapter 8 – Poor Joey

Chapter 9 – Christmas Capers

Chapter 10 – The Tricycle

Chapter 11 – Jekyll and Hyde

Chapter 12 – Another Nail in the Coffin

Chapter 13 – Adoption – Hope or Despair?

Chapter 14 – Finny

Chapter 15 – Schooldays and Holidays

Chapter 16 – Leaving School

Chapter 17 – The Next Step

Chapter 18 – The Motorbike

1971–85: THE ESCAPE

Chapter 19 – A Room with a View

Chapter 20 – Crash!

Chapter 21 – A Second Escape

Chapter 22 – Crossroads … and a New Life

1986–2019: THE TRUTH

Chapter 23 – Opening Pandora’s Box

Chapter 24 – Closing the Circle

Acknowledgements

About the Publisher

1954: ABANDONED

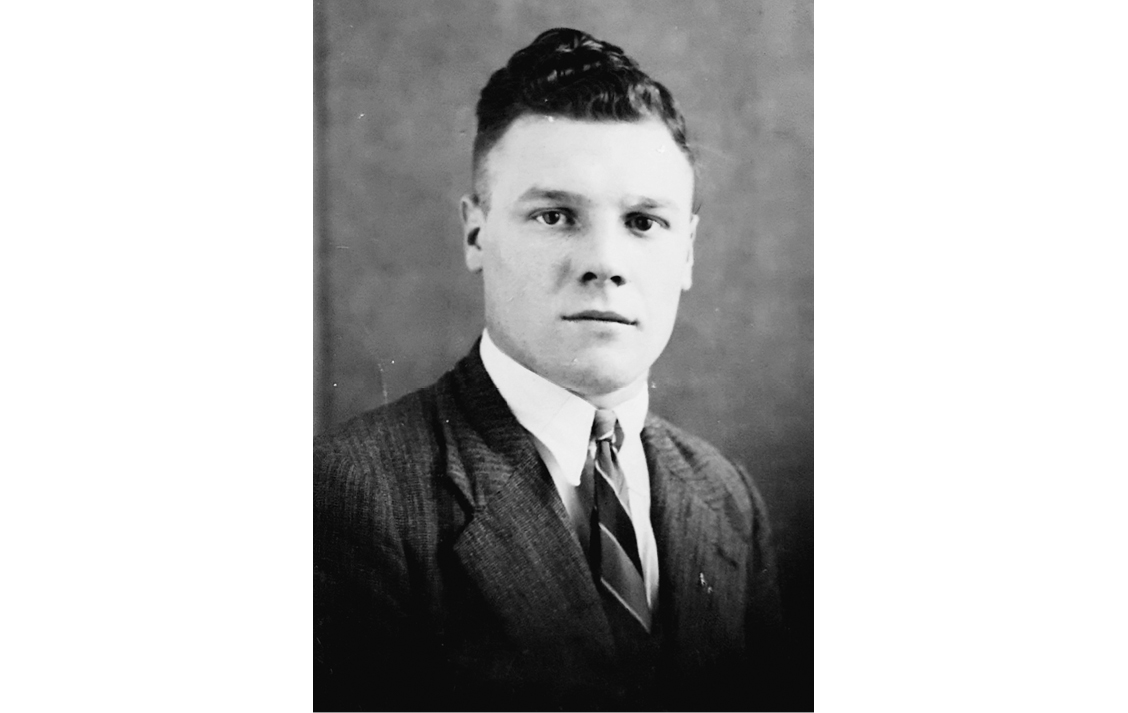

© Ray Bryant

CHAPTER 1

Left to Die

‘What was that?’ The whispered words faded to echoes in the dark mists of that frozen night, 17 November 1954.

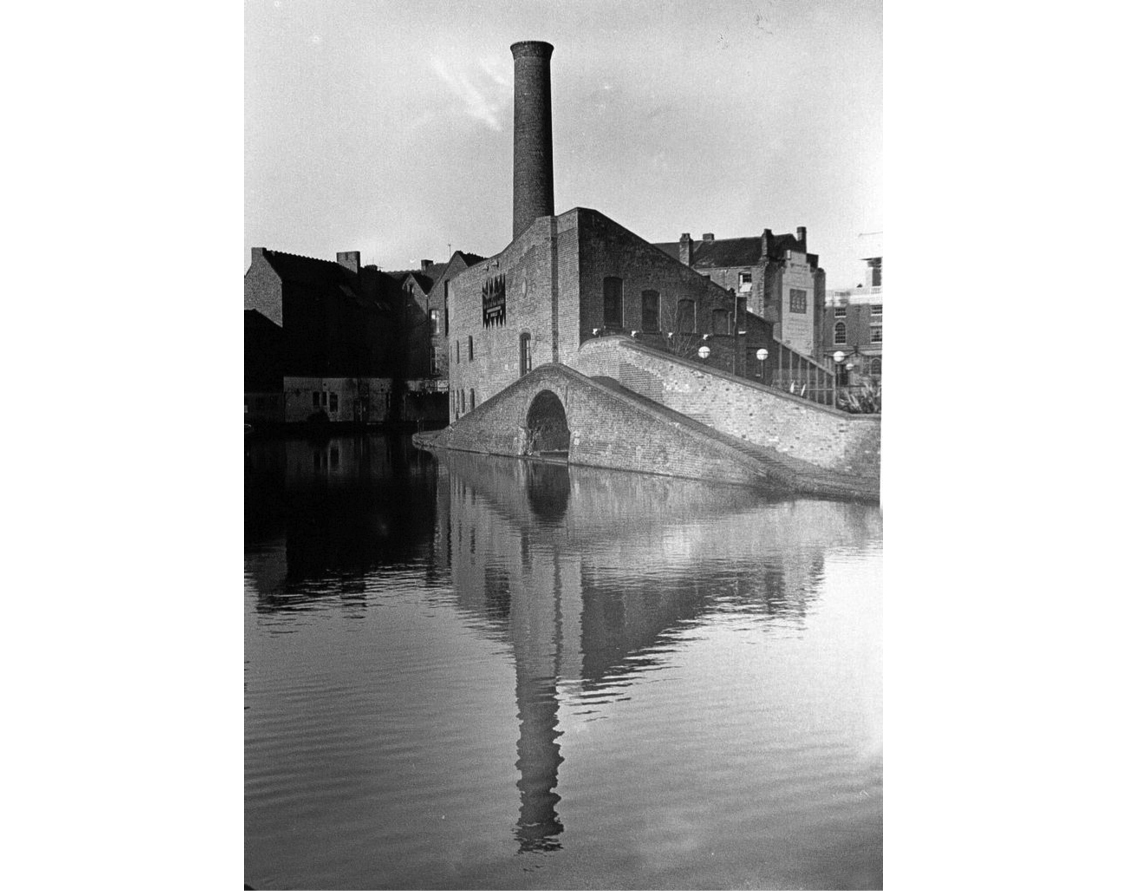

Postman Joseph Lester had just finished his shift at Birmingham’s sorting office and started out on his walk home along Gas Street, through the gap in the wall and down to the canal towpath at Gas Street Basin. It was nine o’clock; the temperature was two degrees below zero. Tired and shivering cold, he was keen to get back to his family in Ledsham Street and relax in front of a roaring fire. This was his usual shortcut home, so he knew his way through the fog that thickened the darkness and stayed well clear of the water’s edge. There was nobody about – just the unseen lapping of water and the muffled, almost inaudible sounds of the city all around … until that faint something, a sort of whimper.

Joseph pointed his torch where he thought it came from, but he found it almost impossible to see anything. He retraced his steps and tried again, shining the beam to and fro over the water and straining his eyes to pick any form out of the darkness. As he moved his torch for one last sweep over the canal, the beam caught something pale. Was it his imagination? Had it moved?

There it was again. An eerie sound, was it a wounded animal? Surely even a rat wouldn’t venture out on this wintry night. But rats aren’t usually pale coloured. Could it be a kitten, or maybe the shape was just a piece of paper?

Joseph hesitated. It was probably nothing worth stopping for, but something niggled at him, making him turn back from his homeward path. He picked his way over the main bridge and round the basin to the other side, where he knew there was another low bridge, which was about where he thought the pale object must be. Sure enough, as he approached it from the back, he heard that sound again, fainter still. Whatever it was, he needed to find it soon. He clambered down and under the bridge, ducking to shine his torch through the profuse undergrowth.

‘There it is!’ he said out loud to himself, reaching what looked like a parcel wrapped in newspaper, only two or three inches from the water’s edge. But this was no normal parcel. As he peeled back the paper, he found inside a scrawny newborn baby, white, cold and whimpering. Joseph was shocked beyond belief: he’d seen rats as big as cats down there, capable of attacking this baby or pushing him into the canal.

He wrapped him up again and placed him inside his coat, holding him close to try to warm him, and turned to go back up to the street, where he knew there was a phone box to dial 999. Police Constable Watson came to meet Joseph and took his name, then noted down his brief account of finding the baby.

‘Well done, mate,’ he told him. ‘You might have saved a life tonight.’

Joseph smiled and went on his way, back to his wife and children. Meanwhile, the policeman hailed a squad car and took the baby straight to the Accident Hospital, where he was rushed through and seen straight away. A nurse gently opened up the two layers of newspaper and removed the thin, stained blanket beneath. She gasped when she saw the baby’s roughly cut umbilical cord.

‘Do you think the mother gave birth alone?’ she asked.

‘Yes, it looks like it,’ said the doctor. ‘And he looks underweight, probably premature.’ Clearly shocked, he examined the boy. ‘He’s only about two hours old, and his temperature is very low,’ he said as he gently rubbed the baby’s fragile skin in an attempt to warm him up. ‘He’s suffering from exposure. It’s touch and go, I’m afraid.’

Another nurse arrived and weighed him before swaddling him in a soft, warm blanket.

‘Call the night sister,’ ordered the doctor. ‘And see if you can find the Chaplain. This baby needs to be baptised, he may not survive the night.’

The night sister came and the Chaplain too.

‘What name shall I give him?’ he asked.

‘Any ideas?’ the night sister asked the nurses.

‘He looks like a Richard,’ suggested one of them, so that was the name he was given.

‘We must transfer him to Dudley Road Maternity Hospital,’ said the doctor. ‘They can put him in an incubator to give him the best chance. Can you arrange that please, Sister?’

As they waited for the paperwork to be completed, the nurses gathered round baby Richard, who had by now regained a little colour and started to cry and kick his legs up. Everyone smiled to see him protesting.

‘He’s a determined little mite,’ said the doctor. ‘He might just make it.’

One of the nurses accompanied the baby in an ambulance to the Dudley Road Maternity Hospital, where they were better equipped to look after him.

On admission to Ward D6 and placed in an incubator, Richard rallied and his temperature normalised. Not only did he survive the night, he became the nurses’ favourite.

Meanwhile, the next day’s newspapers were full of articles about the abandoned ‘canal-side baby’. The headlines read: ‘BABY LEFT ON CANAL BANK’, ‘NEW-BORN BABY FOUND WRAPPED IN NEWSPAPER’, ‘CHILD FOUND UNDER BRIDGE’, ‘POLICE SEARCH FOR MOTHER’. In fact, the police used the newspapers to put out pleas for the mother to come forward, or for any information, but there was no response. It seemed the baby would have no parents named on his birth certificate.

Almost hour by hour, Richard’s condition improved and he began to flourish. ‘DAY-OLD BABY IMPROVING’ was one of the second day’s headlines.

Later that day, a woman was brought into Dudley Road Maternity Hospital and admitted for treatment, suffering complications after giving birth. She gave her name and address, but would say no more. However, with the press still badgering the hospital for news of the abandoned baby’s progress, an astute nurse suspected a link. The police were alerted and sent round a constable to question the woman in her hospital bed. At first silent, her weakened state left her vulnerable. Within minutes, she broke down and admitted she was the woman they were looking for. However, she didn’t give much away at that stage – just that she had given birth that evening at her lodgings (a story that would later prove to be untrue) and wandered round with the baby, tired and confused, before laying him down under the canal bridge.

While in hospital, it seems, she did not request to see the baby. However, had she asked, she would not have been permitted to visit him while the police were investigating the case.

The next morning’s newspapers triumphantly carried the story on their front pages: ‘CANAL-SIDE BABY: MOTHER TRACED’ and other similar headlines.

Now the police charged her with abandonment and started to gather evidence from postman Joseph Lester, PC Watson, the first policeman on the scene, the doctor at the hospital where the baby was first admitted, and anyone else they could find.

On 22 December, Richard’s birth mother was in the dock at Birmingham Magistrates’ Court, where she had no alternative but to plead guilty to ‘abandoning the child in a manner likely to cause it unnecessary suffering or injury’. The press reported the case in considerable detail.

The prosecution set out the evidence, explaining how the baby was found by the canal, very close to the water’s edge, and the state he was in: ‘The weather was bad. Exposure had endangered the baby’s life and it was not likely the child would have lived, but for the keen observation of Mr Lester.’

The mother’s counsel told the court that she was afraid of losing her lodgings and possibly her job too. ‘And the fact that the baby was born prematurely, when she got home from work,’ he explained, ‘caused her to act in an unnatural manner.’

‘I hope you realise the gravity of your offence,’ the magistrate scolded her. All the available evidence, which was not very much, was heard. Finally, the magistrate looked straight at the mother and said: ‘You might have faced a charge of infanticide, for what you did could have resulted in the child’s death.’

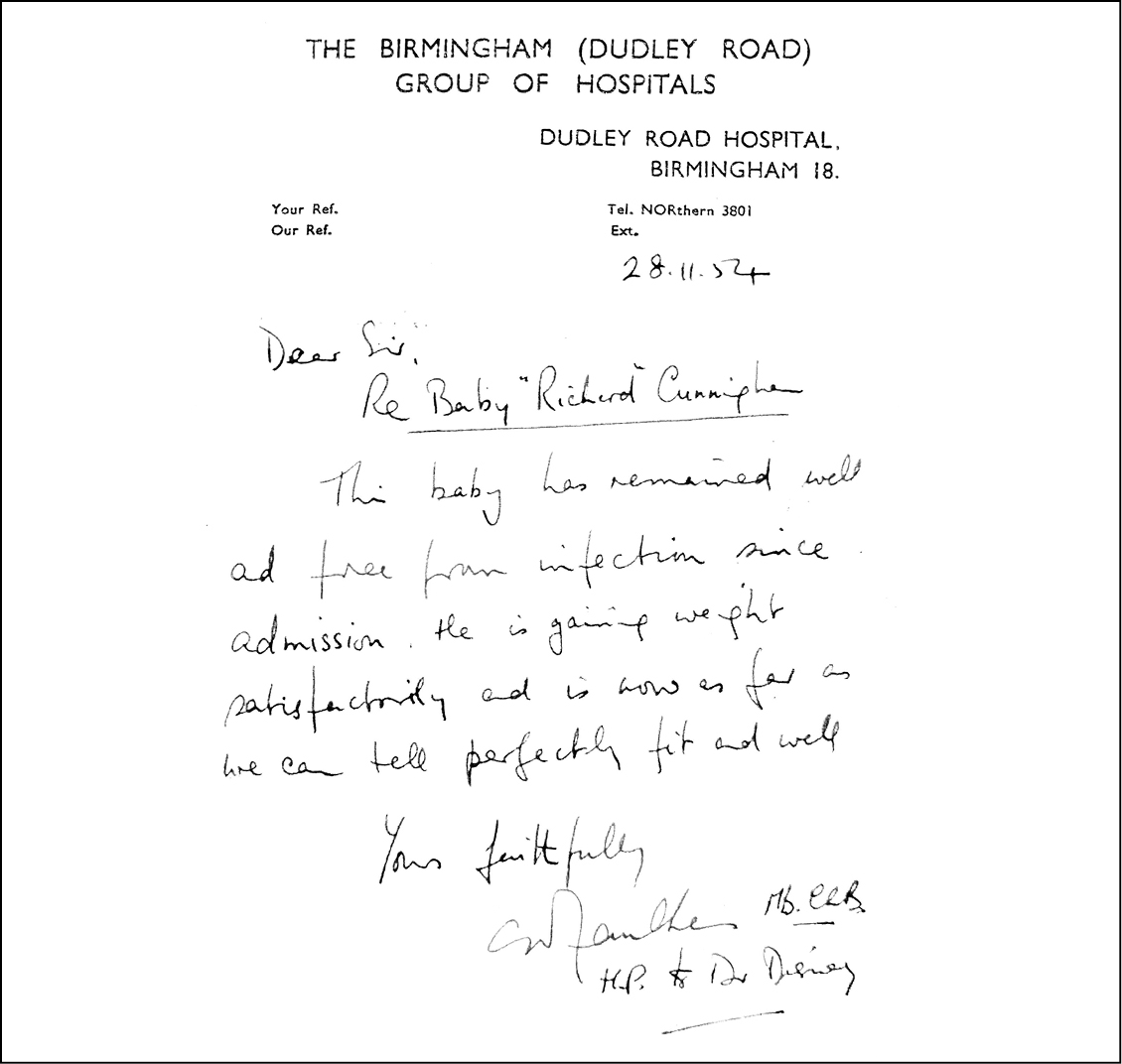

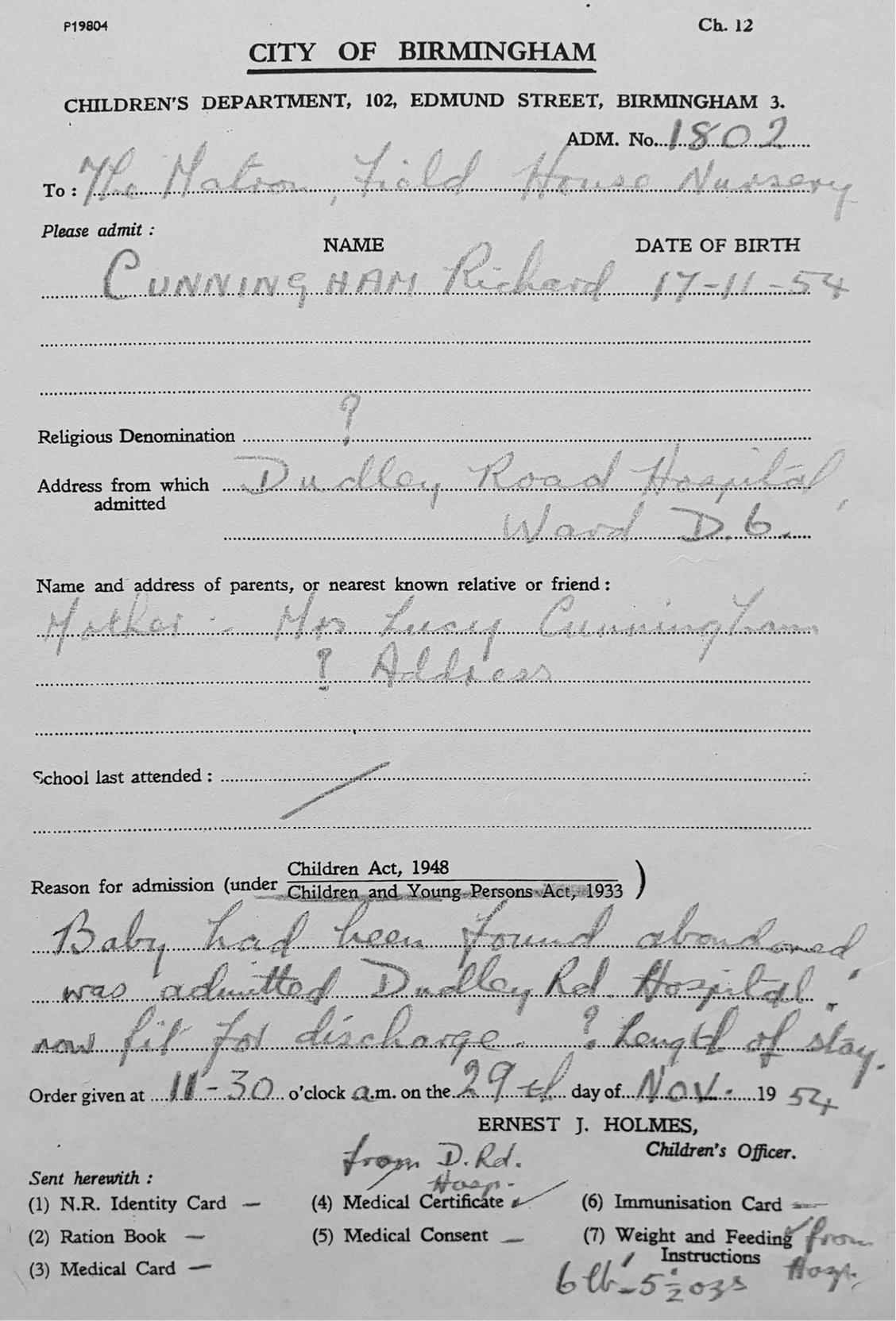

Oblivious to all this, baby Richard was basking in the affection showered on him by the nurses in Ward D6 and only a day or two after his arrival was well enough to thrive outside the incubator. He fed hungrily and was soon ready to be discharged from hospital. On 28 November, just 11 days after his birth, the duty doctor wrote a letter to Birmingham Children’s Officer:

The following day, a form was filled in at Birmingham Children’s Department to take over responsibility for him.

That afternoon, the nurses gathered to wave off baby Richard as he was handed over to a woman from the Children’s Department, who took him to Field House Nursery – the place that would become his first real home.

1954–59:THE EARLY YEARS

Field House © Annette Randle

CHAPTER 2

Field House

December 1954 (1 month old) – Appears a normal child for age. Plump and round.

September 1955 (10 months old) – A happy, fair child. Can sit and crawl. Goes after toys and is responsive and friendly.

August 1956 (nearly 2) – Growing taller. Jealous of baby in his ‘family’. Happy and jolly in between times.

Field House progress report

Friends are often amazed at how vivid my early childhood memories are. My earliest recollection is from the age of about two and a half to three. I was running around the huge lawn in front of Field House, enjoying the freedom of space in the sunshine, when I was excited to find a metal watering can lying on the grass. I must have seen the gardener watering plants, because I knew what to do with it. With some difficulty, because it was quite big and heavy for me, even though it was nearly empty, I picked it up. Inside, I saw a little water at the bottom, so I half-carried, half-dragged it across the grass to a flower bed – I suppose I thought the flowers needed watering and I remember trying to lift the spout to pour water over them. I was thrilled when a trickle came out and wetted the earth around one of the plants. That memory has always stayed with me and I’ve loved gardens and gardening ever since.

I know it’s a cliché, but the sun always seemed to shine at Field House and I was a happy child. That’s what I remember most – being happy, whether playing with the other children or exploring on my own. Those memories have comforted me ever since.

As a child, I was always hungry. I don’t know why because at mealtimes we had a lot of food and the staff encouraged us to eat as much as we wanted. Every now and then I would run through the grand front door (which was always open) and across the hall to the kitchen to see what I could find.

As I approached the kitchen one day I could smell the steak pie they were cooking for our lunch – my favourite. When I peeked in, round the kitchen door, I saw a trolley with several loaves of sliced bread, all wrapped in waxed paper. One was already open, with half taken out. I reached for it and looked inside to see if it had any burnt crusts – I always loved the burnt loaves best. This one looked just right, so I turned around with it, and as I carried it out, I saw one of the cooks smiling and winking at me. They were all so kind – I think I amused them with my cheeky ways. I ran outside again, across the lawn and found my favourite tree, whose branches swept the ground. After clambering up on one of those branches, I ate the crusts from each piece of bread. I was in Heaven! It seems strange now, but nobody ever told me off for taking the bread – or for climbing the tree for that matter.

I often sat in that tree and gazed at the beautiful house, with its tall windows arranged in a pattern on each grand facade. At that stage, as far as I knew, I hadn’t seen any other buildings at all, so I didn’t realise how lucky we were to live in such an elegant mansion, with its mown lawns, ancient cedar trees and wonderful views of the Clent Hills. Every day, I watched Matron drive in or out in her little car, a pale green Austin A30, which she parked on the gravel to one side of the house.

When I wasn’t running around or climbing trees, I used to take myself off for a walk around the outside of the building. We were all friends at Field House, but from a very early age, I enjoyed being on my own as well. I loved to see what was happening in the large, walled vegetable garden behind the house. All our vegetables were grown there and I enjoyed watching them day by day as they came up out of the ground and revealed their produce. To me, the whole process seemed like magic! We grew our own fruits too. Often in the summer we’d have raspberries and strawberries and in the autumn the cooks made us delicious apple crumbles. Blackberries grew abundantly in the hedgerows lining our drive, so we would each be given a little basket to pick some – under supervision, of course. I remember eating most of mine, but some must have been taken back to the kitchen because they were often added to the crumbles.

All the year round, the kitchen’s delicious smells lured me in, again and again. Often the best times were when the cooks were baking cakes. I have to admit that every now and then, when I thought they weren’t looking, I would pop in and pinch an iced bun or a slice of Victoria sandwich from a plate – I loved that. The cooks never seemed to mind. The head cook was a large and jolly woman. In fact, all the staff seemed jolly to me. Whoever appointed the people to work at Field House, with children from all different backgrounds and circumstances, they chose very well. If any of us had a problem, from a scraped knee to a crisis of confidence or a terrifying nightmare, there was always somebody on hand to comfort us.

There were several housemothers and I think we each had one special one who would take particular care of us and encourage us to do the right things and to play well with each other. I can remember my housemother as if I saw her yesterday – very slim, with straight dark hair and a kind, smiley face. She was very bubbly and I loved her for that. I only wish I could remember her name. I suppose each housemother must have had responsibility for two or three children at a time and sometimes, especially when the new babies came in, I think I may have been a little jealous of the attention she paid them. However, as far as I can remember, I was quite an easy-going child and always happy to make my own amusements.

Sometimes, at night, I remember waking up to find I had wet the bed. This wasn’t unusual at Field House, but it did upset me and I couldn’t help crying. I don’t know how they knew, but my housemother, or one of the others, would always come and change the sheets and calm me down with soothing whispers and a cuddle until I fell asleep again.

The matron was different. We all had to call her ‘Matron’ and so did all the staff – it wasn’t Joan, or Mrs Smith, or anything like that, it always had to be ‘Matron’. A tall woman, she was quite thin and stern. I remember she did sometimes have a kindly face, but most of the time she was strict and everyone was a little afraid of her. She was that old-fashioned sort of matron they used to have on hospital wards to make sure that everything was clean and tidy. Nothing got past our matron! We were all wary of her – nobody ever said ‘boo’ to Matron. I think the staff were all wary of her too – they were constantly cleaning. As soon as that little green car came up the drive, crunching the gravel, and drew up outside, I noticed the great flurry as everybody started doing things!

While all the housemothers were kind to us, they sometimes had to be quite strict as well, to make sure we did the right things and followed the routines as much as possible. If we were asked to line up on the front lawn, that’s what we did. And if it was time for lunch or an afternoon lemonade, we had to stop what we were doing and come straight away. I don’t remember a bell – the staff just came out and found us around the grounds and gathered us in.

Although the house was big, we only really used the ground floor. In all, there were about 20 to 25 children, plus the babies, who were in a separate part of the house. There were at least as many staff as there were children. I can still remember the uniforms the housemothers wore: striped dresses with belts round their waists and pure white tabards slipped over the top.

Although the doctor usually came to do vaccinations and check-ups on our progress, writing down his findings on special forms, there were other times when he was called out to someone who was ill. We all had the usual illnesses, being together so much and passing them on to each other. I know from my medical records that I had whooping cough when I was two and I remember the doctor coming to see me when I had measles, aged three and a half. But the worst thing I ever had was salmonella food poisoning when I was about three, because I had to be taken to Hagley Green Hospital in the doctor’s car. I must have been very ill with it as I was kept in for about five weeks.

Throughout the summer, the staff would sometimes organise games for us, like taking turns hitting the ball. But I never joined in those games for very long as I lost interest in balls and bats. Instead, I would go off to a little den I’d made and study the insects that hid under the logs.

I wasn’t really interested in group games. For me the biggest entertainment was the gardens, the beautiful place we lived and the countryside around it – I just loved playing there. I looked at the buttercups and how they were made; I watched the butterflies flitting about and settling, so that I could study the patterns on their wings.

One day, my housemother came over and sat on the grass with me, watching the bees buzzing over a clump of lavender. ‘I like bees,’ she said. ‘They are good for the flowers, taking pollen from one to another and back to their hives, where they make honey.’

‘Really?’ I asked in wonder. ‘Do the bees make our honey that we sometimes have at teatime?’

‘Yes, that’s right,’ she nodded with a smile.

‘But they sting, don’t they?’ I continued. ‘David had a bee sting.’

‘Not usually, only if they feel threatened. David was trying to hit them with his bat. Bees only sting if they think we are trying to hurt them, but wasps are the ones you want to look out for. They can give you a nasty sting, so best to stay clear of them.’

‘How do I know if it’s a wasp?’

As my housemother explained the differences, I took it all in and never forgot it. From an early age I was fascinated by nature and loved to learn about it.

As well as organised games and a large amount of space to build dens and trees to climb, we had swings and small climbing frames, which we took turns on.

I don’t remember having any best friends at Field House because we were all friends together – I liked everybody and none of them were horrible or selfish, so we just got on. We missed the older ones when they had to leave, but new children came in to replace them and it was all part of the pattern of our lives. We were all different ages under five, so it was like a big family. Yes, that’s exactly the right word: it was the ethos of the place, we all felt loved and looked after. We took it for granted, cocooned as we were from the outside world, not knowing that children’s homes could be any different.

Of course, children were occasionally naughty and they would have their legs slapped. If they were very naughty, they would have to go and see Matron. That induced the fear, oh yes! Just the thought of it put them off doing anything naughty again.