Полная версия:

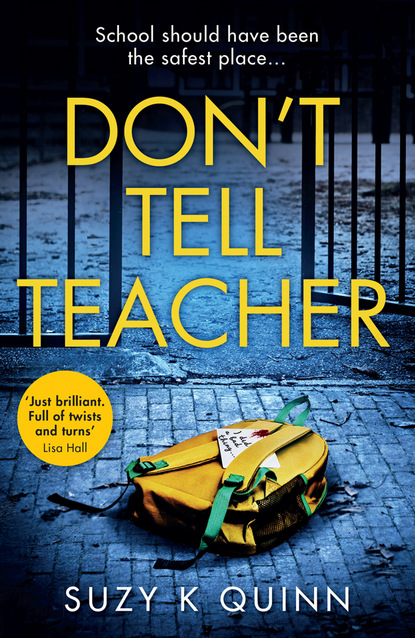

Don’t Tell Teacher

I write, pen-marks jerky.

‘You keep the medicine cabinet in your office?’ I ask.

‘Pardon?’ Mr Cockrun takes back the notebook.

‘Don’t you have a nurse’s office?’

Mr Cockrun smiles again, a wide version that still doesn’t reach his eyes. ‘As I said, Mrs Kinnock, there’s method to our madness. Don’t worry.’ He pats my shoulder. ‘We have it all under control. Let me show you to the gate.’

We walk slowly across the playground, me watching my plain lace-up DMs tap tap over tarmac.

On my way home, I see a dead bird. There’s a lot of blood. I suppose a fox must have got it.

It’s right by the hole in the school fence – the one I saw before, repaired with a bike chain. The hole is very small. Not big enough for an adult to climb through.

There’s probably some logical explanation.

Given my past, it would be strange if I didn’t get twitchy about odd things. But there’s no need to be paranoid.

Lizzie

‘Look, keep still. It’s broken.’

I put my hand on Olly’s knee, which bulges at an eye-watering angle under his padded O’Neill trousers.

He’s lying on thick snow, one ski boot bent back under his snowboard, the other boot snapped open, his socked foot falling out.

Under the bright morning sunshine, Olly’s blue eyes water, tanned skin squeezing and contorting. He has English colouring – sandy hair dusting his ski goggles and an unnatural orange hue to his suntan.

‘I’m pretty lucky to have a nurse here,’ says Olly, after another wince of pain. ‘Have I told you I love you yet today? I do. I love you, Lizzie Nightingale. Remember that, if I die out here on this slope.’

He doesn’t realise how serious this is.

‘I’m not a nurse yet. Don’t try to move.’

Olly, of course, makes a stupid attempt to get up, pushing strong, gloved hands onto the snow. But then his eyes widen, his skin pales and he falls back down. This is just like him. Give him a boundary and his first impulse is to overcome it.

‘Please don’t move,’ I beg. ‘God – this is awful. I can’t bear seeing you hurt.’

Olly reaches up to trail fingers down my cheek. ‘Is it bad that even in all this pain, I still want to do things to you?’

‘You know, there are times for jokes. And this isn’t one of them.’

‘I’m not joking.’ He gives me the soft, blue eyes that make my stomach turn over. ‘We could have sex right here on the snow. The ambulance will take ages.’

‘Olly. You’ve just broken your leg.’

‘I get it. You can’t have sex in public until we’re married.’ He heaves himself onto his elbows and grasps my fingers. ‘So marry me, Lizzie.’

‘I just said this is no time for jokes.’

‘I’m not joking. You’re the one for me, Lizzie Nightingale. I knew it from the moment I saw you stumbling along that icy path in your big purple coat, looking like a little elfin angel thing. I promise I will take care of you for the rest of my life.’ He gives another wince of pain. ‘Even if I never walk again.’

Olly is so impulsive. A risk-taker. I suppose that goes hand in hand with snowboarding. He goes full-pelt into everything. Including love.

In a few short weeks, he’s made me feel so special and adored. Lying in Olly’s chalet bed, wrapped up in his arms, watching snow fall outside, I have never known love like this – utterly consuming, can’t-be-apart love.

He makes me breakfast every morning, constantly tells me how beautiful I am and texts me all day long.

I’m waiting for him to work out who I really am. Just a nobody. And then this holiday romance will come crashing down.

‘Just lie down and rest,’ I say, stroking his forehead. ‘They’ll take you to hospital. I’ll bring you chocolate Pop Tarts.’

Olly loves sugar. He’s a big kid, really. So enthusiastic. And when we’re in bed he’s like that too – just ‘wow!’ at everything. ‘Wow, you look incredible, wow your body is amazing.’

He makes me feel so alive. So adored. So noticed. The exact opposite of how my mother makes me feel.

How did this happen so quickly?

I’m so in love with him.

Olly lies back on the snow, staring up at the sky. ‘I’ll heal. Won’t I? I’ll be able to compete?’

He looks right at me then, blue eyes crystal clear.

‘I don’t know, Olly. Just try to rest. The paramedics will be here soon.’

Olly reaches out a snowy, gloved hand and takes my mitten. ‘You’re an angel, Lizzie Nightingale. You have fabulous dimples, by the way.’

I smile then, without meaning to.

‘You will stay with me, won’t you?’ Olly asks, suddenly serious. ‘Until the stretcher comes?’

‘Of course I will. You fall, I fall. Remember? We’re in this together.’

I sit on the cold snow, my mitten clasped in his glove.

Kate

1.45 p.m.

I take deep breaths, lifting knuckles to the door. The red-brick house is identical to its neighbours – except for the large crack in the front door.

Knock, knock.

No answer.

Tessa’s words ring in my ears: Get on to that Tom Kinnock case as soon as possible. He should never have been passed over to us. Get it shut down and off your desk.

I would peer in the window, but the curtains are closed, even though it’s gone lunchtime.

Knock, knock.

I put an ear to the door and hear voices. Someone is home.

Knock, knock, knock.

‘Hello?’ I call. ‘It’s Kate Noble from Children’s Services.’

I knock again, this time with a closed fist.

There are hurried footsteps and a woman opens the door, blonde hair scraped back in a hairband.

‘Keep it down.’ The woman’s eyes swim in their sockets. ‘Alice is sleeping.’

So this is Leanne Neilson. Mother to the infamous Neilson boys.

She wears Beauty and the Beast pyjamas with furry slippers and looks exhausted, huge bags under her eyes. Her grey pallor is a drug-abuse red flag. Unsurprisingly, the files note that Leanne has a problem with prescription medicine.

Behind Leanne is a tidy-ish living room with red leather sofas and a shiny flat-screen over a chrome fireplace. The voices, I realise, were coming from the television.

‘You must be Miss Neilson,’ I say, reaching out my hand. ‘Lloyd, Joey and Pauly’s mum. Can I call you Leanne?’

Leanne Neilson isn’t the person I wanted to see today. I should be at Tom Kinnock’s house, getting his file shut down and letting his mother get on with her new life.

But social services is all about prioritising highest need.

‘All right,’ says Leanne, tilting her head, eyes still rolling around, not taking my hand.

‘So my name is Kate. I’m your new social worker.’

Leanne blinks languidly, grey cheeks slackening. ‘What happened to … er … Kirsty?’

‘She’s been signed off long-term sick.’

‘What do you want?’ A rapid nose scratch. ‘I’ve been in hospital.’

‘Yes – that’s what I wanted to chat to you about. Can I come in for a minute?’

Leanne looks behind her. ‘I mean, the house is a mess.’

‘It looks okay. Are the sofas new?’

‘Leather is … easier to clean. But give it a few weeks and Lloyd … he’ll wreck them.’ More rapid nose scratching.

‘Can I come in?’

‘When is Kirsty back?’

‘She probably won’t be coming back.’

‘Another one gone then.’ Leanne walks back into the lounge, her hand going to the sofa arm for support.

I close the front door.

‘Where’s baby Alice?’ I ask.

‘I told you. Sleeping.’

‘Can I see?’

‘This is like a … roundabout,’ says Leanne. ‘“Can I see the bedrooms? How are things with your partner? How are you coping?” I never see the same person twice. No one ever gives me any help.’

‘We don’t like changing staff either, Leanne,’ I say, following her up the pink-carpeted staircase. ‘It’s bad for everyone when people leave. But it’s just the way things are at the moment.’

‘Alice is here,’ says Leanne, lowering her slow voice to a whisper, and showing me a clean, relatively tidy baby room with five large boxes of Pampers stacked in the corner.

Baby Alice is asleep in a white-wood cot with a mobile hanging overhead. The room smells fine – unlike the landing, which has a faint odour of urine.

‘I know it smells,’ says Leanne, as if reading my mind. ‘Joey’s still wetting the bed. The doctor says he’ll grow out of it.’

‘How did this happen?’ I ask, pointing to a hole in a chipboard bedroom door.

Leanne blinks a few times, then responds: ‘Lloyd did that. I’ve told the housing people. They still haven’t been round to repair it.’ She adds, ‘It wasn’t my partner, if that’s what you’re asking.’

‘Has Lloyd started counselling yet?’ I ask. ‘He should be nearing the top of the waiting list by now.’

‘No.’ Leanne’s face crumples. She looks at me then, brown eyes filled with pain.

I know what she’s saying. I can’t cope. And suddenly I want to hug her.

But we’re not allowed to do that with adults.

‘Lloyd talked with the last social worker about coping strategies,’ I say, following the official line. ‘Boxing at his cousin’s gym? Has he been doing that?’

‘I’m his punch bag,’ Leanne says. ‘He’s getting so big now, I can’t stop him. I’ve asked them to take him into care. No one listens. He’s going to kill me one of these days.’

‘Let’s talk about how you can set boundaries. Look into some parenting classes—’

‘I’ve been to them.’

‘No. They were organised for you, but you didn’t attend.’

‘I couldn’t get there. I don’t have a car.’

‘I’ll set up some more classes for you. Maybe I can look into having someone drive you there. What about your medication? Are you taking it regularly?’

‘Yeah, yeah, I’m taking it.’ Leanne’s eyes dart to the floor. ‘But I lost some. Can you tell the doctor to give me more?’

‘You’d have to ask him yourself. Let’s talk about your partner. Are you still with him?’

‘Why do people always ask about him? What has he got to do with anything? I’m allowed to have a boyfriend. I’m a grown woman.’

‘He’s living here, isn’t he?’

Leanne thinks for a moment, eyes rolling around. ‘It’s my house,’ she says. ‘Why is it anyone else’s business who lives here? Look, can’t you take Lloyd into care, just for a bit?’

‘I can’t pick up a child and place them in care just like that.’

‘Why not?’

Because they have to be deemed at risk of immediate harm. And Lloyd is more of a risk to others than in danger himself.

Lizzie

‘So how was school?’

Tom is quiet, head down, kicking stones. I squeeze his hand in mine.

We’re walking home along the country path, me shielding my eyes against the low sun.

My little boy seems so small beside me today. It’s funny – when he started school in London, he grew up overnight. But now he seems young again. Vulnerable.

He hasn’t grown much this year, even though he’s nearly nine.

‘It was all right,’ says Tom. His school jumper is inside out, so he must have had sports today. He never has quite got the hang of dressing himself. ‘Were you okay at home?’

I laugh. ‘I was fine, Tom. You’re such a lovely boy for caring. High five?’

Tom slaps my fingers, but doesn’t smile.

‘Do you need me to carry your bag?’ I ask. ‘You look tired.’

He doesn’t reply.

‘Tommo?’

‘What?’ Tom turns to me, eyes dull. He looks … disorientated.

‘Are you okay?’

He nods.

‘You don’t look okay. What’s up, Tommo?’

‘Just tired.’

‘How was school?’

‘I don’t remember.’ Tom’s words are soft now – almost slurred.

My heart races, but I keep my questions calm. ‘Nothing? Not even what you had for lunch? Tom … you don’t look too well. Maybe you should have a lie-down on the sofa when we get home.’

‘Yeah.’ His feet trudge over stones.

I remember chatting with another mum in London once.

Usually, I kept my head down at the school gates, the quiet, downtrodden wife. But this mum sought me out. Forced me into a conversation.

She told me her son, Ewan, never remembered what happened at school. She said it was common.

I’d nodded, feigning agreement. But actually, Tom always remembered his school day. Our walk home was filled with chatter about reading books, school dinners and gold stars.

‘Okay, champ.’ I ruffle Tom’s hair, the words catching. ‘A little rest. And then I think a trip to the doctor’s would be a good idea.’

‘Yeah.’ Tom stumbles a little, his black school shoe turning under itself.

‘Tom?’ I take his arm.

He gives a languid blink. ‘Maybe … maybe I’m getting a cold. Everything looks blue today.’

I stiffen.

When things were especially bad between Olly and me, Tom became fixated on colours. How grass wasn’t really green, but green, yellow and brown. And the teacher’s skirt was ‘turquoise like Daddy’s sweatshirt’.

A sign of stress, the doctor said.

We approach our sleeping house, the curtains drawn. They’re made from thick, heavy velvet, and I hung them the very first day we moved.

Heavy curtains are a necessity for anyone running from someone.

‘Do you want something to eat?’ I unlock the front door. ‘I bought some biscuits. You can have a snack and I’ll take your temperature.’

‘I don’t want a snack,’ says Tom, heading straight through our messy living room and throwing his coat and bag over the bannisters. ‘Biscuits are too brown today.’

Too brown.

He hasn’t mentioned colours since we left London …

‘I just want to sleep,’ says Tom.

‘Can’t we just have a little chat?’

Out of the blue, Tom snaps: ‘Leave me alone! I hate the new school, okay? And I hate you.’

I stare at him, utterly stunned. He’s never talked to me like that. Ever.

‘Maybe you should go upstairs and rest,’ I say sharply.

‘That’s what I just said,’ he retorts.

Clump, clump, clump.

Tom stomps up the stairs, head bowed. Then his bedroom door slams.

I follow him upstairs and find him sitting on his bed, playing with his Clarks shoes. He pulls the Velcro back, then sticks it down. Rip, rip. Rip, rip.

‘Tom? Please let’s talk. I know this is hard.’

Tom looks up, and as he does his head begins to loll around.

Then my little boy slides to the floor, his body totally rigid, twisting, biting, drooling.

‘Tom!’ I stare, terrified, as he snaps his teeth at thin air. One hand is still locked to the Velcro on his trainer, his body a stiff crescent, fingers refusing to yield. ‘Tom!’

I see the whites of his eyes as he shouts, ‘School grey.’

‘I’m phoning an ambulance,’ I shout, dashing downstairs two steps at a time.

My fingers are shaking as I dial 999, my words rushed when the operator comes on the line. ‘Help, please,’ I sob. ‘My son is having some sort of fit. Please send an ambulance. Hurry!’

Lizzie

I have nausea – the sort brought on by overwhelming fear and anxiety.

Oh God, oh God, oh God.

Tom lies on white cotton sheets. They’re the same sheets I used to strip down in hospitals before I got pregnant. They should feel familiar and safe, but today everything is wrong.

My eyes are wide, barely blinking. ‘Why did this happen?’ I ask the doctor. ‘He’s a healthy child. He’s healthy.’

Tom stopped convulsing when the ambulance came. He is now drowsy and confused, barely conscious. A seizure – that’s what they’re calling it. Nobody knows why it happened.

‘Could he have taken anything he shouldn’t?’ the doctor asks. ‘Medication, anything like that? It’s quite unusual for this to happen with no history.’

‘No. We keep paracetamol, cough syrup. He has painkillers for migraines … but Tom wouldn’t take anything without asking. He’s very sensible for his age.’

‘Normal painkillers wouldn’t have caused something like this.’

‘Tom,’ I whisper.

‘Mum,’ Tom says.

‘Sweetheart.’ I stroke his forehead.

Tom murmurs, ‘I want to sleep. Please, Mum.’

‘You haven’t eaten. The sooner you eat, the sooner we can get home to your own bed. With all your Lego.’

‘Red Lego. Want to … sleep.’

‘Tom, the doctor wants to know if you took anything. Medicine – anything like that.’

Tom shakes his head, eyes bobbing closed.

When the doctor leaves, Tom sleeps until teatime.

He wakes to eat three forkfuls of hospital meat pie and one spoonful of strawberry yoghurt.

While I’m clearing Tom’s dinner tray, a nurse says: ‘You’ll be discharged later. Just as soon as the doctor comes back.’

I nod, shelving the empty tray in a metal trolley.

‘Tom will be in his own bed tonight,’ the nurse continues. ‘And back at school tomorrow. That’ll be nice, won’t it?’

‘Yes.’

But actually, the thought of school … it frightens me.

Kate

What’s the time? My watch hands point to 7.10 p.m., but the computer says 7 p.m.

The computer is right, of course – I always set my watch ten minutes fast. Col calls this my mega efficiency.

I see Tessa in her office, stuffing Nespresso capsules into her handbag.

‘I need you here first thing tomorrow,’ she commands, striding past me. ‘Did you get the Kinnock file closed down yet?’

‘Tom Kinnock’s mother still hasn’t replied to my letter. She’s had it over a week now. I need to pencil in an unannounced visit. See how Tom’s settling into his new school before I close the case down.’

‘Don’t forget your twenty-nine other children.’

‘Thirty children now, Tessa. And yes, I know.’

‘Don’t cancel anything you shouldn’t.’

There is a secret code in social services. Some appointments absolutely can’t be altered. Some shouldn’t be altered, but have to be.

It all comes down to greatest need.

‘Okay, listen. Why not forget about Tom Kinnock for the time being?’ Tessa suggests. ‘You have a cast-iron defence if anything goes wrong – blame Hammersmith and Fulham. They should have passed it over sooner.’

‘I need to make a start,’ I say. ‘Get some sort of order. The file has passed through ten different social workers – the notes are an absolute mess. Pages and pages of reports, everything out of order. It needs straightening out.’

‘Hammersmith and Fulham sound worse than this place,’ says Tessa. ‘Can you imagine? Somewhere more chaotic than here?’ She snorts with laughter and heads towards the swing doors. ‘Well. Night then.’

I put my head in my hands.

At university, I was always ‘Sensible Kate’ or ‘Aunty Kate’. The one with a good head on her shoulders. I never broke down or got overwhelmed. But right now, I’m stressed to the point of collapse.

‘Are you all right?’

My head jerks up, and I see Tessa lingering in the doorway.

I feel embarrassed and pat my cheeks. ‘Fine. I thought you’d gone.’

‘You’re not all right, are you?’ Tessa backtracks, perching her large behind on my desk. ‘You’re killing yourself. Staying late every night. This can’t be doing your love life any good. What does your boyfriend think about all this?’

‘Husband.’

‘Oh, that’s right. I can never get my head around that. At your age.’

‘Col’s getting used to my working habits. I used to text him if I’d be home late. Now I text if I’ll be home on time.’

Tessa guffaws. ‘Sounds about right. But how long will he be understanding for? A lot of relationships break down here. Partners get fed up of being second best.’

‘Col and I are solid. We support each other.’

‘Listen, with a caseload like yours, you’ve got to put some of them on the back burner.’

‘Tell me, Tessa – how can I put a vulnerable child on the back burner?’

Lizzie

Mum is visiting today. She wants to talk about Tom’s first week at school. Make sure he’s settling in okay.

Two things will happen.

She will be late.

She will criticise me incessantly.

I’ve made vegetable soup with organic parsnips and carrots, and just a little bit of crème fraîche, plus (I won’t tell my mum this) a squirt of tomato ketchup. Pumpkin seed and olive oil bread warms in the oven.

I have been up early, cleaning, scrubbing, dusting. The house looks great, actually. A real step forward. I’ve laid the breakfast bar in the big, beautiful conservatory using freshly laundered napkins and antique wine glasses.

But I know it won’t be enough. Nothing ever is for my mother.

It’s 1 p.m., and Tom waits in a clean shirt, face scrubbed, hair shiny. He tried to get out of brushing his teeth (‘I’ll do it later, Mum’), but I managed to bribe him with a fruit Yoyo and the promise that he doesn’t have to give Grandma a kiss.

Now we’re sat on the sofa, listening for the click click of my mother’s high heels.

A car slows outside. I hear footsteps, then a hard knock at the door.

This is her.

I open the door to a cloud of rose perfume and Mum’s glossy, denture-perfect smile. She looks like a Fifties movie star – red lipstick, bright green pashmina and Jane Mansfield coiffed black hair.

‘Hello, darling.’ Mum kisses me on both cheeks, leaving traces of lipstick, which I surreptitiously rub off. She glides into the house, sharp, green eyes inspecting. ‘How is my little grandson?’

‘He’s much better now,’ I say. ‘They didn’t keep him overnight in the end. They think the seizure could have been a one-off. Just some unexplained childhood thing. Tom, say hello to your grandma.’

‘Hello, Grandma,’ says Tom, back straight, knees together. ‘That’s a very nice red bag.’

‘Have they put him on any medication?’ Mum asks.

I hesitate. ‘Yes. Yes, they have. Blood-thinning meds, just in case. He’s going to be on them for the next few months and then they’ll reassess.’

‘So he’s on prescription medication?’ Mum qualifies. ‘It must be serious, then.’

‘I … yes. He’s still not quite himself.’

‘How are you settling into school?’ Mum asks. ‘Are you keeping up with your school work?’

‘Yes,’ says Tom. ‘It’s harder than London, but it’s all right.’

‘Did I mention, Thomas – I met your new headmaster?’ Mum slides leather gloves from her hands and pats his head. ‘I liked him very much. Behave well for him, won’t you? We don’t want people thinking you’re from a bad family. How are you doing in class? Still at the top?’

‘No,’ says Tom. ‘Not here. But I don’t mind.’

‘You need to work hard, Tom,’ says Mum. ‘Don’t be lazy. You were top of the class before. The headmaster is such a nice man. Very high standards. He’ll be disappointed in you.’

‘Tom has never been lazy,’ I say. ‘He’s just not competitive. He doesn’t care about being the best. That’s just not who he is.’

‘Not like his father then.’ Mum raises an eyebrow. She walks through the living room and into the kitchen, opening and closing cupboards. ‘So this is where you’re hiding the mess.’

It’s true – there’s a raggle-taggle heap of objects stuffed inside the lower cupboards. Things I didn’t have time to sort through and stuffed out of the way to look tidy.