Полная версия:

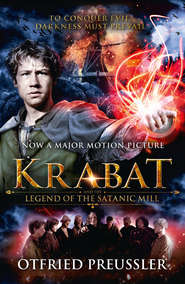

Krabat

‘I just don’t see how you can put up with it!’ he said.

‘What, me?’ asked Juro in surprise.

‘Yes, you!’ said Krabat. ‘The Master treats you shamefully, and all the others laugh at you!’

‘Tonda doesn’t,’ Juro objected. ‘You don’t, either.’

‘What difference does that make?’ cried Krabat. ‘I know what I’d do if I were you. I’d stick up for myself, that’s what! I wouldn’t take it any more – I wouldn’t take it from Kito or Andrush or any of them!’

‘Hm,’ said Juro, scratching the back of his neck. ‘Maybe that’s what you’d do, Krabat – well, you could! But what if you were just a fool like me?’

‘Well, run away, then!’ cried the boy. ‘Run away from here! Find somewhere else where they’ll treat you better!’

‘Run away?’ And for a moment Juro did not look stupid at all, merely tired and sad. ‘Try it, Krabat! Try running away from here!’

‘I don’t have any reason to!’

‘No,’ muttered Juro, ‘no, of course you don’t – let’s hope you never do …’

He put a crust of bread in the boy’s other pocket, cut short his thanks, and pushed him out of the door, a silly grin on his face just as usual.

Krabat saved his bread and sausage until the end of the day. Soon after supper, while the miller’s men were sitting in the servants’ hall, Petar busy with his whittling and the rest passing the time by telling stories, the boy left them and climbed up to the attic, where he threw himself down on his straw mattress, yawning. He ate his bread and sausage then, and as he lay there enjoying his feast, his thoughts went back to Juro and their talk in the kitchen.

‘Run away?’ he thought. ‘Run away from what? It’s no bed of roses here, with so much hard work to do, and I’d be in a bad way without Tonda’s help. But the food’s good, there’s plenty of it, I have a roof over my head – and when I get up in the morning, I’m sure of a bed for the next night, warm and dry and reasonably soft, with no bugs or fleas in it. That’s more than I could ever have hoped for when I was a beggar boy!’

CHAPTER FOUR A Dream of Escape

Krabat had run away once in his life already, soon after the death of his parents, who had died of the smallpox the year before. The pastor had taken him in, ‘to stop the child running wild,’ said he, which was much to the credit of the good pastor and his wife, who had always wished for a boy of their own. But Krabat, who had spent all his life in a wretched hovel, the shepherd’s hut at Eutrich, found it hard to settle down in the pastor’s house and be good all day long, never shout or fight, wear a white shirt, wash his neck and comb his hair, not go barefoot, keep his hands clean and his fingernails scrubbed – and on top of all that he had to speak German the whole time instead of Wendish!

Krabat had tried as hard as he could. He tried for a whole week, and then another week, and after that he ran away from the pastor’s house and joined the beggar boys. He was not absolutely certain that he wanted to stay at the mill in the fen of Kosel for good, either.

‘All the same,’ he decided, licking his lips as he finished the last morsel, and half asleep already, ‘all the same, when I run away from here it’ll have to be summertime … no one’s getting me to leave before the wild flowers are out, and the wheat’s springing in the fields, and the fish in the millpond are biting …’

It is summer, the wild flowers are out in the meadows, the wheat is springing, the fish in the millpond are biting. Krabat has quarreled with his master; instead of carrying sacks of grain, he lay down in the grass in the shadow of the mill and fell asleep, and the Master caught him at it and hit him with his big stick.

‘I’ll teach you to be idle in broad daylight, young man!’ the miller shouted.

Was Krabat to put up with such treatment? In winter, with the icy wind howling over the moor, perhaps he’d have to take it. Aha – the Master was forgetting that it’s summer now!

Krabat has made up his mind. He won’t stay in this mill a day longer! He steals into the house, takes his coat and cap from the attic, and then slips away. No one sees him. The Master has gone back to his own room, the blinds are down over the windows because of the hot weather, the miller’s men are at work in the granary and tending the millstones, even Lyshko is too busy to bother about Krabat. Yet the boy still feels that someone is secretly watching him.

When he looks around, he does see a watcher on the woodshed roof, sitting there staring at him – a rough-haired black tom cat, a cat that doesn’t belong in the mill. It has only one eye.

Krabat bends to pick up a stone, throws it at the cat and shoos it off. Then he hurries toward the millpond, under cover of the willows. He catches sight of a fat carp in the water by the bank. It is goggling up at him with its one eye.

Feeling ill at ease, the boy picks up a stone and flings it at the carp, which dives away, plunging down into the green depths of the pond.

Now Krabat is following the Black Water to that place in the fen of Kosel that folks call the Waste Ground. He stops there for a few minutes, by Tonda’s grave, remembering vaguely how they had to bury their friend here one winter’s day.

He stands there thinking of the dead man … and suddenly, so unexpectedly that his heart misses a beat, he hears a hoarse croak. There is a large raven perched motionless on a stunted pine at the edge of the Waste Ground. It is looking at Krabat, and the boy sees with horror that it, too, has no left eye.

Now Krabat knows where he stands, and wasting no time, he begins to run, running away as fast as his feet will carry him, going upstream along the Black Water.

When he first stops to get his breath back, a viper comes wriggling through the heather, rears up, hissing, and looks at him – it has only one eye. The fox watching him from the undergrowth is one-eyed, too.

Krabat runs, stops for breath, runs on, stops again. Toward evening he comes to the far side of the fen. When he comes out into the open, so he hopes, he will be out of the Master’s reach. Quickly, he dips his hands in the water, splashes his forehead and temples. Then, tucking in his shirt, which had come adrift as he ran, he tightens his belt, takes the last few steps – and freezes with horror.

Instead of coming out on the open moor, as he expected, he finds himself in a clearing, and in the middle of this clearing, in the peaceful evening light, stands the mill. The Master is waiting for him at the door of the house.

‘Why, if it isn’t Krabat! There is mockery in his voice. ‘I was just about to send someone out to search for you!’

Krabat is furious. He cannot understand what went wrong. He runs away again, early in the morning this time, before daybreak, in the opposite direction, out of the wood, over fields and meadows, through villages and hamlets. He leaps over watercourses, he wades through a bog, he never stops to rest. He ignores ravens, vipers, foxes; he does not glance at fish or cat, chicken or drake. ‘They can have one eye or two, or be stone-blind for all I care!’ he thinks. ‘I won’t be led astray this time!’

All the same, at the end of the long day he is standing outside the mill in the fen of Kosel again. This time the miller’s men are there to welcome him back, Lyshko with malicious remarks, the others silently and with sympathy in their eyes. Krabat is near despair. He knows it would be best to give up, but he refuses to admit it. He tries again, a third time, that very night.

It is not difficult to slip away from the mill … now he will guide himself by the North Star! What does it matter if he stumbles and gets scratched and bruised in the dark? No one sees him, no one can cast any spell on him, and that is the main thing.

Not far away, an owl hoots, and then another bird flits past. Soon after that he spots an old eagle owl in the starlight; it is sitting on a branch, within his reach, and watching him – with its right eye. Its left eye is missing.

Krabat runs on, falling over roots, stumbling into a ditch. He is not much surprised, when day breaks, to find himself standing outside the mill for the third time.

All is still quiet indoors at this hour, but for the sound of Juro at work in the kitchen, busy making up the fire. Hearing him, Krabat goes in.

‘You were right, Juro. No one can run away from here. ’

Juro gives him something to drink. “You’d better go and wash, Krabat,‘ he says. He helps Krabat off with his wet, muddy, bloodstained shirt, fills a pitcher of water, and then seriously and without his usual foolish grin, he says, ‘You couldn’t do it on your own, Krabat… but perhaps it might be done by two. Suppose we both try another time?’

Krabat was awakened by the sound of the miller’s men coming upstairs to bed. He still had the taste of the sausage in his mouth, he could not have slept long, even though he had lived through two days and two nights in his dream.

The next morning he happened to be alone with Juro for a moment or two.

‘I dreamed of you, Juro,’ said Krabat. ‘You suggested something to me in my dream.’

‘I did?’ said Juro. ‘Well, it must have been nonsense, Krabat, and you’d better just forget about it!’

CHAPTER FIVE The Man with the Plumed Hat

The mill in the fen of Kosel had seven sets of millstones. Six sets were always in use, and the seventh never; they called those millstones the Dead Stones. They stood right at the back of the grinding room. At first Krabat thought part of the cogwheel must be broken, or the main shaft was stuck, or some other part of the machinery damaged, until one morning, as he was sweeping the place out, he found a little flour lying on the floor boards around the chute that led down to the meal bin under the Dead Stones. On closer inspection, he found traces of fresh flour in the meal bin, too, as if it had not been knocked out well enough after the work was done.

Had the Dead Stones been grinding grain last night? If so, it must have been done in secret, while everyone was asleep … or were they not all sleeping as soundly as Krabat himself last night?

He remembered that the miller’s men had turned up for breakfast looking pale and hollow-eyed that day, and many of them were yawning, which struck him as suspicious now. Impelled by curiosity, he climbed the wooden steps up to the bin floor, where the grain was tipped from its sacks into the funnel-shaped hopper, from which it ran over the feed shoe and so down between the millstones. As the men tipped it in, a few grains were bound to be spilled, only it was not grain of any kind lying there under the hopper, as Krabat expected. The things lying around the bin floor looked like pebbles at first sight, a second glance showed Krabat that they were teeth – teeth and splinters of bone.

Horrified, the boy opened his mouth to scream, but he could not utter a sound.

Suddenly Tonda was there, behind him. Krabat had not heard him coming. He took the boy’s hand.

‘What are you after up here, Krabat?’ he asked. ‘Come along down, before the Master catches you, and forget what you have seen here, do you hear me, Krabat? Forget it!’

Then he led Krabat down the steps, and no sooner did the boy feel the boards of the grinding-room floor under his feet than all he had seen that morning was wiped clean out of his mind.

During the second half of February, a severe frost set in. The miller’s men had to break the ice outside the sluice every morning. Overnight, while the wheel stood still, the water would freeze in the grooves of the paddles, forming thick crusts of ice, which had to be hacked away before the machinery could be started up.

Most dangerous of all was the ice that formed in the tailrace below the mill wheel. To keep it from damaging the wheel, two men had to climb down from time to time and hack it out, a job that none of them was particularly keen to do. Tonda made sure that no one shirked it, but when it was Krabat’s turn the head journeyman climbed down into the tailrace himself, saying it was no work for a boy who might hurt himself doing it.

The others made no objection, except for Kito, who grumbled as usual, and Lyshko, who said, ‘Anyone might hurt himself if he didn’t look out!’

Whether by chance or not, stupid Juro happened to be passing just then with a bucket full of pig swill in each hand. As he came past Lyshko he stumbled and splashed him with the pig swill from head to foot. Lyshko swore, and Juro, wringing his hands, assured him he could kick himself for being so clumsy.

‘Just think how you’ll smell for the next few days!’ said he. ‘And it’s all my fault … oh dear, Lyshko, don’t be cross with me, please don’t! I feel so sorry for the poor pigs, too!’

These days Krabat often went out felling trees in the wood, with Tonda and some of the others. As they set off in their sleigh, well wrapped up, hot oatmeal inside them, their fur caps crammed down on their foreheads, he felt so good in spite of the bitter cold that he envied no one in the world.

The trees they felled had their branches lopped on the spot, were stripped of their bark, cut to the right length, and stacked up loosely, with crossbars running between each layer to let the air in between the trunks, before they were taken to the mill next winter to be made into beams or sawn up for planks and boards.

So the weeks passed by, and nothing much changed in Krabat’s daily life. He noticed a good many things that made him stop to think. For a start, it was odd that no customers ever came to the mill. Were the local farmers avoiding it? Yet the millstones ground every day, and grain was always being poured into the hoppers – barley and oats and buckwheat.

Did the flour that was poured from the meal bins into sacks by day turn back into grain overnight? It seemed perfectly possible, Krabat thought.

At the end of the first week in March the weather changed. A west wind sprang up, driving gray clouds across the sky. ‘There’ll be snow,’ muttered Kito. ‘I can feel it in my bones!’ And it did snow a little, large, watery flakes, before the first raindrops came splashing down and the snow turned to a downpour.

‘I tell you what,’ said Andrush to Kito. ‘You’d better keep a tree frog to tell you what the weather will be – there’s no relying on your bones these days!’

It rained cats and dogs, the rain poured down in torrents, whipped along by the wind, melting snow and ice, and making the millstream rise alarmingly. The men had to go out in the rain to close the sluice and shore it up with props.

Would the sluice gate hold against the rising water?

‘If it goes on like this we’ll all be drowned along with the mill before three days are up!’ thought Krabat.

On the evening of the sixth day the rain stopped, there was a break in the blanket of clouds, and for a few moments the rays of the setting sun shone through the dark, dripping wood.

The next night Krabat had a frightening dream. Fire had broken out in the mill. The miller’s men jumped up from their straw mattresses and clattered downstairs, but Krabat himself lay on his bed like a log of wood, unable to move from the spot.

Flames were already crackling in the rafters, and the first sparks were showering down on his face, when he woke with a yell.

He rubbed his eyes and yawned, looking around him. All of a sudden he froze, unable to believe his eyes. Where were the miller’s men?

Their beds were empty, deserted; they seemed to have left in a hurry, since the blankets were hastily pushed back and the sheets crumpled. Here was a jacket on the floor, there a cap, a muffler, a belt – all clearly visible in the reflection of a red light flickering outside the gable window …

Was the mill really on fire?

Wide awake now, Krabat flung the window open. Leaning out, he saw a cart standing outside the mill. It was heavily laden, a canvas cover, dark with the rain, was stretched tightly over it, and a team of six horses, every one of them as black as coal, was harnessed to it. Someone was sitting on the box, his collar pulled up high, his hat well down over his forehead, and all his clothes were black as night, too. Only the feather he wore in his hat was bright red. It was wavering in the wind like a flame flickering, now blown upward, glowing bright, now drooping as if it would go out. It was bright enough to light up the whole front yard of the mill.

The miller’s men were hurrying back and forth between the house and the covered cart, unloading sacks, dragging them into the mill, running out again. They worked in complete silence and feverish haste. Not a shout nor a curse could be heard, only the panting of the men, and now and then a snap as the driver cracked his whip right above their heads, so that they could feel the wind of it. That spurred them on to redouble their efforts. Even the Master was hard at work, though he usually never did a hand’s turn in the mill, never lifted his little finger. But tonight he was working with the rest, competing with his men as if he were being paid for it.

Once he stopped work for a moment and vanished into the darkness, not for a rest, as Krabat suspected, but to run to the millstream, move away the props and open the sluice.

The water shot into the millrace, came rushing along and poured over into the tailrace, surging and slapping. With a creaking sound, the wheel began to turn, it was some time before it really got going, but then it went smoothly around. And now the millstones ought to start grinding, with a hollow groaning noise, but there was only one set of stones working, and that one set of stones worked with an unfamiliar sound. Krabat thought it seemed to come right from the back of the mill, a noisy clatter and thud, accompanied by an ugly squealing sound which soon turned to a howl that tormented the listener’s ears.

Krabat remembered the Dead Stones, and his flesh began to creep.

Meanwhile work was still going on down below. The covered cart was unloaded, and the miller’s men had a break – but not for long. The work went on again, though this time they were carrying the sacks back from the house to the cart. Whatever those sacks had contained, it was now ground and was being brought back.

Krabat meant to count the sacks, but he nodded off to sleep in the middle. At first cockcrow the rumble of cartwheels awakened him, and he was just in time to see the stranger drive away over the wet meadow, cracking his whip, going toward the wood – and strange to say, heavily laden as it was, the cart left no tracks behind it in the grass.

A moment later the sluice was closed and the mill wheel ran down. Krabat jumped back into bed and pulled the covers up over his head. The miller’s men came staggering upstairs, tired to death. They lay down on their beds in silence, only Kito muttering something about ‘these accursed nights of new moon’ and ‘a fiendish job.’

In the morning Krabat was so tired he could hardly get up. His head was throbbing, and he had a queasy feeling in his stomach. At breakfast he looked at the miller’s men, they were sleepy and bleary-eyed and surly as they ate their oatmeal. Even Andrush was disinclined to make jokes; he stared gloomily at his plate and did not say a word.

After breakfast Tonda took the boy aside.

‘Did you have a bad night?’

‘I – I’m not sure,’ said Krabat. ‘I didn’t have to work, I was just watching. But what about you? Why didn’t you wake me when the stranger came? I suppose you wanted to keep it secret from me – like all the other things that go on at this mill, and I’m not to know about them! But I’m not deaf or blind, you know, and I’m no fool, either, not by any means!’

‘No one said you were!’ protested Tonda.

‘But that’s the way you all act!’ cried Krabat. ‘You’re playing some kind of game with me! Why don’t you stop it?’

‘All in good time,’ said Tonda quietly. ‘You’ll learn all about this mill and its master soon enough. The day and the hour are nearer than you know. Be patient until then.’

CHAPTER SIX The Ravens’ Perch

Early on Good Friday evening there was a pale, bloated moon hanging in the sky above the fen of Kosel. The miller’s men were sitting together in the servants’ hall, while Krabat, worn out, was lying on his bed trying to get to sleep. They had had to work on Good Friday, too. He felt thankful it was evening at last, and he could get some rest …

All of a sudden he heard his name called, just as it was in the dream he had in the smithy at Petershain, only now he knew the hoarse voice that seemed to come out of thin air.

He sat up and listened, and the voice called again. ‘Krabat!’ Reaching for his clothes, he got dressed.

When he was ready, the Master called him for the third time.

Krabat made haste, groped his way to the attic door, and opened it. Light shone up from below. Down in the hall he heard voices, and the clatter of wooden clogs. Feeling uneasy, he hesitated, holding his breath – but then he pulled himself together and ran downstairs, three steps at a time.

The eleven journeymen were standing at the end of the hall. The door to the Black Room stood open, and the Master was sitting behind the table. Just as on the day of Krabat’s arrival, the thick, leather-bound book was lying in front of him, and there was the skull, too, with the red candle burning in it. The only difference was that the Master was not so pale in the face now.

‘Come closer, Krabat!’ he said.

The boy came forward, to the threshold of the Black Room. He did not feel tired now, nor did he notice his dizziness or the throbbing of his heart anymore.

The Master looked him over. Then, raising his left hand, he turned to the journeymen standing in the hall.

‘Up on your perch!’

Croaking and flapping their wings, eleven ravens flew past Krabat and through the door of the room. When he looked around, the miller’s men had disappeared. The ravens settled on a perch at the far end of the room, in the left corner, and sat there looking at him.

The Master rose, and his shadow fell on the boy.

‘You have been at this mill for a quarter of a year now, Krabat,’ said he. ‘Your trial period is over, and you are no longer an ordinary apprentice – from now on you will be my pupil.’

With these words he went up to Krabat and touched the boy’s left shoulder with his own left hand. A shiver ran through Krabat, he felt himself begin to shrink, his body became smaller and smaller, he grew raven’s feathers, a beak, and claws. There he crouched in the doorway, at the Master’s feet, not daring to look up.

The Master looked down at him for a while, then clapped his hands and cried, ‘Up on your perch!’ Krabat – the raven Krabat – obediently spread his wings and rose into the air. Flapping awkwardly, he crossed the room, flew around the table, brushing against the book and the skull, and then settled beside the other ravens, clinging tight to the perch.

‘You must know that you are in a Black School, Krabat,’ the Master told him. ‘You will not learn reading and writing and arithmetic here – you will learn the Art of Arts. The book chained to the table is the Book of Necromancy, which teaches how to conjure up spirits. As you see, it has black pages, and the words are white. It contains all the magic spells in the world. I alone may read them, because I am the Master here. But you – you, Krabat, and my other pupils – you are forbidden to read the Book, remember that! And no going behind my back, or it will be the worse for you! Do you understand that, Krabat?’

‘Yes, I understand,’ croaked the boy, surprised to find he could still speak at all – in a hoarse voice, to be sure, but quite clearly and easily.