Полная версия

Полная версияПозитивные изменения, Том 3 №1, 2023. Positive changes. Volume 3, Issue 1 (2023)

На основании полученных монетарных оценок был проведен уже сам расчет социального возврата на инвестиции, причем как для проекта в целом, так и для каждой группы заинтересованных сторон. Общий показатель SROI для проекта составил 12,45 – то есть на одну турецкую лиру, вложенную в реализацию проекта, получено 12,45 лиры социального эффекта. При этом из этих 12,45 лиры на долю результатов, полученных девочками, приходится 20 % (2,43 лиры), а на долю результатов, полученных родителями, – 38 % (4,68 лиры).

ПРОЕКТНАЯ ОЦЕНКАВ английском языке есть несколько слов-синонимов, которые переводятся на русский как оценка. Проектную оценку мы приравниваем к английскому evaluation. Эта оценка представляет собой комплекс аналитических мероприятий, которые проводятся, чтобы обеспечить лиц, принимающих управленческие решения относительно проекта, необходимой им информацией. Обычно такие решения принимают либо руководители проекта, либо его доноры.

Данный подход предполагает, что еще на этапе планирования проекта будет разработана система его мониторинга и оценки. Основой для разработки такой системы служат результаты анализа заинтересованных сторон и описания механизма работы проекта, которое объясняет, каким образом реализация проектных мероприятий приведет к достижению ожидаемых результатов (такое описание принято называть теорией изменений или логической моделью проекта).

Соответственно, при использовании этого подхода анализ заинтересованных сторон проекта «Девушки на футбольном поле» нужно было бы провести еще на этапе его планирования. После этого нужно было бы построить карту изменений или логическую модель, которая бы объясняла, каким образом мероприятия проекта приведут в итоге к достижению его целей. Построение такой карты могло бы также помочь конкретизировать цели (конечные ожидаемые результаты) проекта. Например, одна из целей сформулирована следующим образом: «Посредством футбола повысить информированность о гендерном равенстве и способствовать более активному участию девочек в занятиях спортом». При разработке карты изменений нужно было бы решить, какая цепочка изменений связывает презентацию по вопросам гендерного равенства для родителей девочек с этой целью: например, более информированные родители поддержат желание дочерей заниматься спортом. На этом этапе могло быть принято решение, что результаты презентации для родителей лучше вынести в отдельную цепочку изменений и добавить еще одну цель проекта.

На основании карты ожидаемых изменений определяют, какая информация потребуется для отслеживания процесса реализации проекта и достижения его результатов. Следующий шаг – решить, кто, когда и как будет эту информацию собирать, анализировать и использовать.

Ключевая задача оценки – помочь руководителям проекта понять, действительно ли реализуется задуманный механизм достижения изменений. Для управления процессом изменений очень важно знать, где в этом процессе происходят сбои. Соответственно, система мониторинга и оценки строится так, чтобы эти сбои выявлять. Кроме того, в проектном управлении сейчас уделяется много внимания незапланированным результатам, как позитивным, так и негативным. Поэтому сбор данных при проектной оценке мог бы быть примерно таким же, как и при описанной выше оценке социального возврата на инвестиции. Но при анализе был бы четкий фокус на то, насколько достигаются запланированные результаты, и какие из незапланированных результатов являются положительными и отрицательными.

Нужно отметить, что расчет SROI или другая монетарная оценка могут быть частью проектной оценки, если эта информация нужна лицам, принимающим решения.

ЭКСПЕРТНАЯ ОЦЕНКАЭкспертную оценку используют обычно тогда, когда социальные результаты проекта по каким-то причинам нельзя измерить. Чаще всего ее применяют организации-доноры для оценки проектных заявок. Оценка – это суждение о ценности проекта, о том, насколько он хорош. При проведении экспертной оценки ее заказчик формирует список критериев – характеристик, которыми должен обладать проект, а эксперты на основании описания проекта в заявке и своих знаний и опыта должны ответить, в какой мере проект соответствует этим критериям. Например, если бы доноры проекта «Девушки на футбольном поле» принимали решение о его финансировании на основании экспертной оценки, они могли бы использовать такие критерии, как соответствие проекта стратегии, результативность проекта – насколько проект способен достичь ожидаемых результатов, экономическая целесообразность проекта – использует ли проект самый дешевый способ достижения ожидаемых результатов или есть более экономичные варианты.

Так как достижение ожидаемых результатов – это главное, чего ждут от проекта, то экспертная оценка может фокусироваться на подробном анализе ожидаемых цепочек изменений. В этом случае экспертам предъявляют подробную карту изменений, составленную разработчиками проекта, и просят оценить вероятность всех связок между результатами, чтобы определить, где возможны разрывы.

Например, при планировании проекта «Девушки на футбольном поле» его авторы могли запланировать следующую цепочку изменений:

• Девочки, которые до начала проекта считают, что футбол – это игра только для мальчиков, проходят полный курс тренировок в академии (пять дней по три часа в день);

• В результате они успешно овладевают базовыми навыками игры;

• Девочки успешно применяют полученные навыки в тренировочных играх;

• Девочки получают удовлетворение и удовольствие от игры;

• Девочки понимают, что идея о том, что только мальчики способны играть в футбол, была ложной;

• Избавление от одного из гендерных стереотипов помогает девочками убедиться в возможности гендерного равенства.

В ходе оценки экспертам нужно будет оценить вероятность того, что достижение очередного результата в этой цепочке обеспечит реализацию следующего шага. Например, если девочки пройдут полный курс тренировок в академии (15 часов), какова вероятность того, что они овладеют базовыми навыками игры?

ЗАКЛЮЧЕНИЕМировой опыт показывает, что проекты, реализуемые в сфере физической культуры и массового спорта, могут создавать как значимые позитивные социальные изменения, так и негативные эффекты. Важным результатом проведенного исследования стала систематизация данных эффектов, что поможет организациям, реализующим и поддерживающим проекты в сфере социального спорта, в их идентификации и оценке. Использование различных видов оценки позволяет выявлять и измерять создаваемые изменения на всех стадиях реализации проекта, что, в свою очередь, помогает лучше управлять процессом изменений. Кроме того, оценка важна для обоснования объемов финансирования и выбора направлений стратегического развития, что особенно актуально в современных условиях, когда все социальные инициативы уже не могут рассчитывать на прежний уровень поддержки из бюджетных и внебюджетных источников.

The Power of Sport. Evaluation of Projects in the Field of Physical Culture and Grassroots Sport

Ilya Solntsev, Natalia Kosheleva

DOI 10.55140/2782–5817–2023–3–1–80–91

In 2020, the Vladimir Potanin Foundation launched the “Power of Sport,” a charitable initiative aimed at uncovering the potential of sports as a social institution. In preparing the launch of the program, the Foundation experts had to study the experience of evaluating project effectiveness, in both an international and Russian context – as well as develop approaches to the selection of promising development areas, including identification and evaluation of effects. To address these problems, the Financial University under the Government of the Russian Federation conducted a study in 2022 aimed at identifying the effects achieved through the implementation of social sports projects and summarizing the approaches used to evaluate them.

Ilya Solntsev

Doctor of Economics, Head of the Department of Management and Marketing in Sports, Financial University under the Government of the Russian Federation

Natalia Kosheleva

Consultant on monitoring and evaluation of social programs and projects, president of the Association of Specialists in Program and Policy Evaluation (ASPPE)

SOCIAL EFFECTS OF SPORTS PROJECTS

Projects implemented in the sphere of physical culture and grassroots sport address a wide range of problems that go beyond the category of “sports”: a number of changes occur in the economy, education and professional sphere, adaptation and socialization, and demography. Sports projects also affect people’s well-being, by changing crime and disease rates. Such a broad range of impacts resulted in the creation of the “Sport for Development” concept, which emerged in the middle of the 20th century. The first scholar to set up its theoretical basis was the American psychologist Gordon Allport (1954), who suggested that contact between different groups of people with different characteristics, including gender, ethnicity and race, was the most effective means of fighting racism, prejudice, and discrimination.

Based on this theoretical framework, Alexis Lyras (2011) suggested that sport initiatives could promote personal development and social change through the use of non-traditional management methods and by combining sports with cultural and educational activities. A number of analytical portals concept are dedicated to the “Sports for Development” concept, for example: Sport for Development[70], and Sport and Development[71], along with multiple studies by global organizations such as UNICEF[72] and the UN[73]. The impact of sports on the society as a whole can be summarized via the UN Sustainable Development Goals[74].

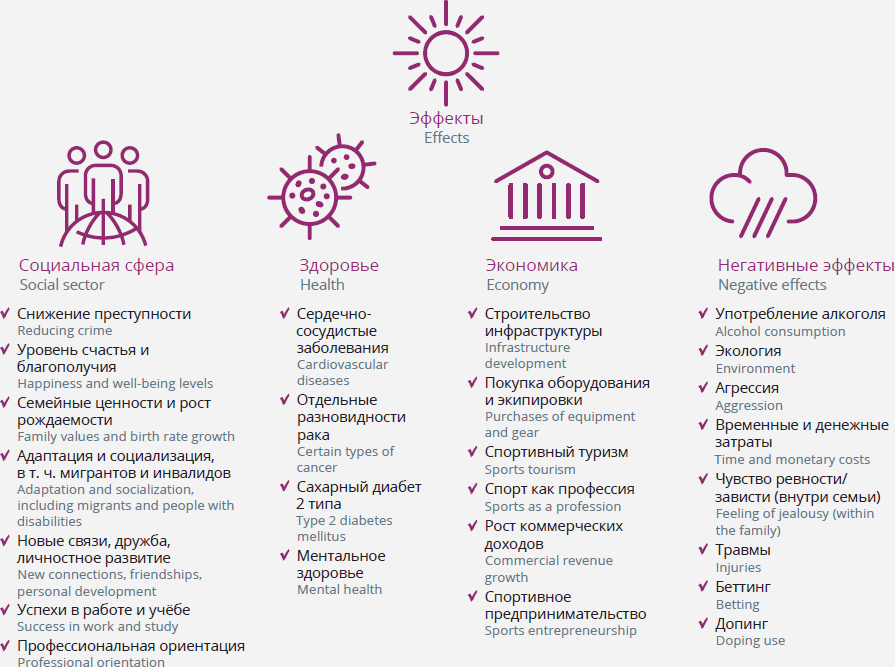

The effects generated by sports projects can be classified into positive and negative, and by the direction of the impact – in the context of the social sphere, health and economy (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Effects generated by sports projects

Source: Vladimir Potanin Foundation. (2022). Social Sports: measuring the effectiveness. Methods for evaluating the effectiveness of social projects in sports.

The positive social and health effects of sports are well summarized and, more importantly, quantified in the work by Larissa Davies et al. (2019):

1. Exercise in sports leads to a 1 % increase in education (11–18 years).

2. Graduates who had engaged in University sports earn 18 percent more a year on average than those who had not.

3. Exercise leads to a 1 % decrease in criminal incidents among men aged 10–24.

4. Participation in sports is associated with higher subjective well-being.

5. Volunteering in sports is associated with improved individual subjective well-being and greater satisfaction with life. The time spent by volunteers is equivalent in value to an average hourly wage.

6. Athletes are 14.1 % more likely to report good health than non-athletes. Sports and moderate-intensity physical exercise in adults, among other things, reduce the risk of:

• coronary heart disease and stroke in active men and women by 30 % on average (between 11 and 52 %);

• breast cancer in active women by 20 % (between 10 and 30 %);

• colorectal cancer by 24 %;

• type 2 diabetes by 10 %;

• dementia by 30 % (between 21 and 52 %).

Researchers from New Zealand reached similar conclusions[75]:

• 84 % of respondents agreed that sports help develop important life skills such as teamwork and cooperation;

• for New Zealanders who participate in sports, the level of well-being increases 59 %;

• sports help develop social skills and make new friends (including for migrants);

• high-performance sports help instill a sense of pride in the country and contribute to national identity;

• physical activity and sports reduce the risk of cardiovascular diseases (7.9 %), type 2 diabetes (9.8 %), dementia (7.7 %), breast cancer (13.1 %), and stomach cancer (14.1 %);

• sports and recreation provide 53,000 jobs and contribute $4.9 billion to GDP annually.

A broad range of impacts resulted in the creation of the “Sport for Development” concept. It was first described by the American psychologist Gordon Allport.

In terms of the impact of sports on the economy, Europe offers noteworthy experience[76]. For example, in 2012, the gross domestic product (GDP) associated with sports was EUR 279.7 billion, or 2.12 % of the total GDP in the EU. In addition, 5.67 million workers can be attributed to the sports industry, which is 2.72 % of the total number. In other words, one in 47 Euros and one in 37 employees in the EU are directly related to sports. These figures were derived from costoutput tables for sports based on national Sport Satellite Accounts.

Indirect multipliers were also used in the calculations, taking into account that each business needs the raw materials from other industries to make its products and/or provide services. Multipliers show how much output from other sectors is needed to produce a certain commodity. For example, producing a sports car requires seats, which in turn requires textiles, etc. The magnitude of multipliers depends primarily on the structure of economic ties between the original sector and the other industries. The more sectors are interconnected, the higher the multipliers. Applying multipliers to direct effects generates indirect effects. For example, if a soccer stadium costs 30 million euros to build (direct effect), and the construction sector reports a multiplier of 1.8, the indirect effect would be (1.8–1.0) x 30, that is, 24 million euros. Note that the supply chain involves national enterprises as well as foreign countries, but the primary effects for the country depend only on the import-adjusted costs.

In terms of economic effects, it is also necessary to consider the athletes’ costs to purchase the equipment, pay for attending the sports sections, travel to competitions (payment for tickets, food, accommodation). In addition, a significant effect can be achieved by the growth of commercial indicators (sponsorship revenues) for those projects that attract a significant audience.

Territorial development[77] is another important effect of many sports projects:

• stimulation of business activity;

• creation of local jobs (including indirectly through construction projects);

• increasing the appeal of the territories and improving their image;

• contributing to the innovation and development of information and communication technologies (ICT) with sporting content;

• greater economic mobility of the population.

In the context of territorial development, it is worth mentioning a whole block of studies devoted to the assessment of economic effects produced by major sport competitions: Gureeva & Solntsev (2014), Baade & Matheson (2004), de Nooij et al. (2013), Preuss (2007), Maennig & Zimbalist (2012).

Numerous studies have documented negative effects of sports as well. For example, it is well known that physical activity can be a stimulus towards alcohol consumption (Lisha et al., 2011). Many studies point to higher rates of alcohol use among athletes compared to non-athlete peers (Leichliter et al., 1998). A common explanation is that athletes tend to celebrate their victories (or experience failure), and teaming encourages this behavior (Leasure et al., 2015).

Sports can also have a negative impact on the environment, including by increasing emissions of harmful substances. For example, Wicker (2019) surveyed adults in Germany and asked them to report their sports-related travel, including in the context of regular (weekly) activities, sports competitions/tournaments, and training camps. The annual carbon footprint was estimated using information on travel distances and vehicles used. The results showed an average annual carbon footprint of 844 kg of emissions (carbon dioxide equivalent), with individual sports providing more emissions than team sports.

Another negative effect is aggression, abusive behavior and violence against competitors and referees. One example is Roman Shirokov, former captain of the Russian national soccer team, beating referee Nikita Danchenkov during the Moscow Celebrity Cup amateur tournament[78]. Peter Dawson et al. (2022) studied the effect of abuse on match officials’ decision to leave their jobs. Based on surveys of soccer referees in France and the Netherlands, the authors investigated factors associated with verbal and physical abuse of referees, as well as the relationship of such abuse to referees’ intentions to leave the profession.

Sports can also have negative effects on relationships within the family. In particular, researchers highlight the high costs of playing sports to families (Kay, 2000; Dixon et al., 2008). Besides the financial obligations, the time costs are also increasing. Tess Kay (2000) notes that the need to exercise affects daily routines and causes changes in vacation plans and work schedules. Negative consequences can vary from increased stress and anxiety (O’Rourke et al., 2011) to decreased self-esteem and trauma (Kay, 2000). Feelings of jealousy and resentment or lack of time for other activities are also noted (Côté, 1999). Tess Kay (2000) found that some children who did not compete felt jealous of their siblings who did participate in sports and felt that their relationship with their parents was not as strong. Finally, it has been shown that parents become less active as a result of their children’s participation in sports (Dixon, 2009).

The effects generated by sports projects can be classified into positive and negative, and by the direction of the impact – in the context of the social sphere, health and economy.

According to UEFA[79], the negative effects of social sports can include injuries, doping use, corruption and the influence of gambling.

PROJECT EFFICIENCY ASSESSMENTSeveral approaches can be used to evaluate the effectiveness of individual projects that use physical activity and sports to achieve social and economic effects, including expert assessment, project evaluation (and monitoring) and monetary evaluation, such as Social Return on Investment (SROI) evaluation. We will consider the similarities and differences between these approaches using the Girls on the Soccer Field project as an example. The project was implemented in Turkey in 2016. Social Return on Investment was calculated for it, and the corresponding report was certified by Social Value, an international network promoting the SROI approach[80].

DESCRIPTION OF THE “GIRLS ON THE SOCCER FIELD” PROJECTThe Girls on the Soccer Field project was created by Melis Abacıoğlu and her company Actifit in 2013. The year before that, Melis and her friends had organized a soccer game for women after their male friends refused to play against them.

The project includes the establishment of a Soccer Academy – for five days, the girls participate in soccer training, as well as creative master classes in visual and theatrical arts and creativity development. In addition, a lecture on gender equality was held for the parents of female Academy participants, who were invited to attend their daughters’ training sessions.

Several approaches can be used to evaluate the effectiveness of individual projects, including expert assessment, project evaluation (and monitoring) and monetary evaluation.

Project goals:

• Through soccer, raise awareness of gender equality and promote greater participation of girls in sports;

• Develop the girls’ creative potential through creative workshops.

EVALUATION OF SOCIAL RETURN ON INVESTMENTThe assessment began with a stakeholder analysis. The following groups were identified: girls participating in the Academy, their parents, volunteer trainers, Actifit (the organization implementing the project), donors who supported the project financially, the foundation that conducted a presentation on gender equality issues for the parents.

The next step in the evaluation process was data collection, which started immediately after the completion of the Academy. The data was mainly collected through survey. Questionnaires were developed for each stakeholder group. These included open-ended questions about participation in the various project activities and the results obtained, for example: “What did you gain from participating in the project? How did the project change your life? Were there any negative consequences of your participation in the project?”

Based on the data collected from all stakeholder groups, their contribution to the project was determined. For example, the girls, their parents, and the volunteer coaches contributed their time; the donors contributed money and sports equipment.

In addition, based on the analysis of the completed questionnaires, the positive and negative results obtained were determined, as well as the relationship between the project activities and results. It is worth noting that this analysis divided the results into expected (planned) and unplanned ones. In case of the girls, for example, the project produced three types of results. First, they became more confident and convinced about the possibility of gender equality. According to the researchers’ analysis, the following chain of changes led to the first result: through soccer training, girls realized that soccer was not just a game for boys, as they had previously thought; besides, soccer training allowed them to appreciate the positive effects of sports, which gave them self-confidence and created awareness of gender equality opportunities. Second, the girls developed imagination and creativity. Third, it was easier for girls to communicate with friends and parents. The authors consider the latter an unplanned outcome of the report, as it was not part of the project goals.

The project results for parents included increased awareness of gender discrimination and improved mutual understanding, as the parents started to communicate more with their daughters. Volunteer coaches have developed communication skills, gained coaching experience, and noted successes in personal growth through participation in the project.

Actifit, which prepared and implemented the project, was able to engage donors, partners and volunteers. Therefore, one of the positive results of the project for the company was saving its own financial resources and employee labor. Additionally, the company was able to make the project more sustainable. Finally, successful operation of the Soccer Academy in Eskisehir was a case study that Actifit can use to further promote its “Girls on the Soccer Field” program. Employee motivation associated with participation in this program has also increased. The negative result of the program was that three employees of the company spent 28 days of their time working on the project.

The next step was monetizing the contributions made by the stakeholders and the results obtained. Only financial and in-kind contribution by Actifit and the donors was taken into account during the monetary evaluation. The report authors decided not to include a monetary evaluation of the time spent on participation in the project by children, parents, and volunteer coaches.

In monetizing the results, the authors used data on the cost of paid services, which would enable the project participants to obtain similar results otherwise. For example, there is a paid soccer section in Eskisehir. The assumption was made that a week of paid soccer lessons would give the girls the same result in terms of developing selfconfidence and understanding the possibility of gender equality, so the cost of this week was used as a “proxy” in estimating the cost of the outcome.

Outside of the project, parents could learn to understand their daughters better and communicate with them more if they took a class with a family psychologist, so the cost of such a course was a monetary estimate for this outcome.