скачать книгу бесплатно

“He spent ten minutes telling Dr. Einhart how he exercises each day.”

“Mom! That couldn’t be further from the truth. Why did you let him do that?”

Essie’s mom blinked. “Do what?”

“Lie to his doctor? It’s ridiculous.”

“But he’s supposed to walk each day. They’ve told him he should walk each day.”

Essie shot out a frustrated sigh. “Well, he doesn’t, does he? We both know he doesn’t.”

“Well, of course he doesn’t. His knees bother him.”

“Mom, we’ve been over this a gazillion times. If he’d walk more, his knees wouldn’t bother him, then he’d drop some of that weight, then his knees would bother him less. It’s just going to get worse if he keeps sitting there. No, no, it’s not just that, but sitting there and lying to his doctor.”

Mom crossed her arms. “I’m not going to make him look bad in front of his doctor.”

Essie wanted to scream. “This is not a popularity contest, this is Dad and his doctor. What’s the point of going to a doctor if you don’t actually tell him what’s going on?”

“How’s Doug, dear?” Mom clipped that thread of conversation clean off. It was quite clear no further discussion on the subject of honesty with one’s doctors would be allowed. Essie fought the urge to go find her father and shake him by the shoulders. Lord, help me. They sure won’t help themselves. Patience, just send gallons and gallons of patience. Right this minute, or I’m going to go out of my mind.

Essie let out a long, slow exhale, rolling her shoulders back as she watched Joshua inspect his thumb. “Doug’s doing fine. The new department has more people and more resources than he had in Jersey, so he’s happy. It’s been a good move for him.”

“That’s nice, dear. Have you talked about having another child? Soon?”

Essie popped her eyes wide open. “Mom, Josh is five months old!”

“I had you and Mark only a year apart. You played so well together.”

Oh, yes, Mom, I have such happy memories of tearing Mark-o apart in joyful siblinghood. Not to mention I’d like to get acquainted with the sight of my toes again.

“Really, Mom, it’s a bit early for that sort of thing.”

“Nonsense. You’re thirty-one. Life won’t go on forever you know. An old woman can pine for grandchildren, can’t she?”

Essie didn’t quite know how to convince her mother she didn’t want to be pregnant for every waking moment of her thirties. Deflect the attention. “You know, there’s always Mark-o. He could have children. He’s married, you know. Married people do that sort of thing.”

Her mother waved a hand as if that were an absurd suggestion. “Oh, yes, but Mark is so very busy with that church. And Peggy—well, I just don’t see Peggy being ready to have children soon. She’s just not that motherly type.”

So I should pop out a gaggle of grandchildren to compensate? And aren’t Doug and I busy? Now that I’m at home with Joshua, is procreation my only purpose in life?

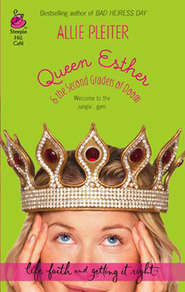

“You, my little Queen Esther.” Essie watched her mother burst into a wide smile. “You were always meant to be a mother. I always knew you’d give me precious, beautiful grandbabies to love.” She scooped up Joshua just as he was dozing off, and made loud snuggly noises into his neck.

Which, of course, sent him into a full-fledged wail.

“I just never thought I’d see the day my Essie fed her children silverware.” Her disapproval of the now-revered grapefruit spoon trick was almost palpable. “Really. No wonder he cries so much.”

He cries so much because you just did the unthinkable: you woke a sleeping baby. A sleeping cranky baby. My sleeping cranky baby that almost never sleeps. Mother-r-r…

“How can such a darling boy be so miserable?” Dorothy made a sour face and handed her “precious grandbaby” back to Essie, obviously unwilling to hold anything making that much noise, even if it was flesh of her flesh.

“He’s teething, Mom. Don’t you remember how miserable a toothache is?” Essie fished around on the couch for the spoon, mentally convincing herself it didn’t need reboiling just because it had endured forty-five seconds on her mother’s couch cushions. She returned it to Joshua’s gaping mouth.

Within fifteen seconds Mount Joshua ceased to erupt. With a dying chorus of wet gurgles, Josh settled into a slow, relieved chew. Essie felt the spoon’s handle wobble up and down as Josh’s besieged gums found their solace. “I know it’s weird,” Essie replied to her mother’s subsequent frown. “But it works. See? It works. I don’t care how, I don’t care why, I just know it works. If putting him in purple socks worked, I’d probably do that, too.”

The front door pushed open and Essie’s dad shuffled in, clutching a white paper pharmacy bag. Mark-o entered behind him, holding a paper bag of groceries. It took Bob Taylor four full minutes to make it from the front door to his permanent spot on the recliner beside the couch. He grunted with every step, and groused with every breath about “those knuckleheaded quacks and their useless pills.”

“I’m gonna spend my pension at that pharmacy,” he grumbled as he eased his large frame into the worn chair. “Every day and every dollar’s gonna buy some drug executive a shiny new yacht.”

“Now, Pop—” Mark-o had put on his counseling persona; Essie could tell by his voice. “If it weren’t for those useless pills, you’d be in the hospital looking at a shiny new wheelchair.”

“Baloney.” Essie’s dad tossed the bag on the coffee table in disgust. “I’m slow, but I’m still moving. Since when is it a sin to get old and slow?”

“At your young years,” Mark shot back, his fraying patience beginning to show through the practiced calm, “it’s a sin.”

“So’s lying.” The words jumped out of Essie’s sleep-deprived mouth before she could think better of it. “As in lying to your doctor.”

“Oh, honey…” began her mother.

“Pop, all she’s…”

Pop’s next booming question stopped the argument in its tracks: “What on earth is that in my grandson’s mouth?”

“Now, who knows the story of Jonah?”

Four cookie-crumbed hands shot up. Essie passed out a second set of napkins before she allowed Justin to answer.

“He got stuck inside a fish.”

Essie smiled. “He sure did. You were listening in assembly this morning, Justin. Who knows how he got there?”

Stanton, a tall boy in pressed pants and gelled hair, strained to get his hand as high as possible. He yipped a series of small “Me! Me! Me!” s. Frantic to be picked, he seemed oblivious to the fact that his was the only hand aloft.

“Stanton?”

“I bet he was swimming. My dad, he took us swimming once, on vacation, and I was really worried about the fishes when we were swimming. I didn’t want to swim where the fishes were, but he told me pools don’t have fishes,’ specially hotel pools. And we were in a hotel ’cuz we were on vacation and stuff, ’cuz we went on vacation over Christmas and we got to go somewhere warm so we could go swimming, but my big brother got in trouble ’cuz he…” The entire speech whooshed out of him in a single breath.

“Okay,” Essie cut in, placing her hand on Stanton’s arm. The boy was wearing a watch. A fancy one. Who buys designer watches for their eight-year-old? Dahlia Mannington, of course. For all his dapper duds, Stanton was a sweet boy with tender green eyes and a near insatiable appetite for attention.

“Swimming is fun. But Jonah wasn’t swimming for fun. Can anyone tell me why Jonah was in the water?”

“It’s hot where he lives!” said Decker Maxwell, as he tipped his chair back far enough to send himself head over heels. The resulting laughter stopped any hope of education dead in its tracks for the next five minutes, as all the other boys tried immediately to follow suit. Essie finally had to resume her lesson on the floor in a circle, without the benefit of chairs. She tried to ignore the sensation of her legs falling asleep as she patiently suggested that Jonah was running from God’s commands.

“Did Jonah get a time-out? I wanna do my time-outs in whale guts!” Peter, a smaller boy with wildly curly hair and an obsession with all things bug-and animal-related, pushed his glasses back up on his face as he joined the conversation.

“Well,” replied Essie, catching a pencil as Stanton sent it through the air in another boy’s direction, “it was sort of a time-out. In one way, God saved Jonah because he wouldn’t have survived being thrown out into the middle of the ocean like that. But in another way, God gave Jonah a good long time to think about what he’d done.”

“My mom does that,” grumbled Peter. “In my ‘Think It Over Chair.’” He crossed his arms over his chest in an exaggerated fashion that made his next comment almost unnecessary. “I hate my Think It Over Chair.”

“Discipline isn’t much fun, is it?” Essie passed around the large blue whales she’d spent two hours cutting out last night.

“What’s dicey-pline?”

“Di-sci-pline.” Essie made a mental note to strike any word over three syllables from her lesson plan. “It’s what your mom or dad does to help you think about something wrong you’ve done.”

“You mean like getting spanked?” Steven Bendenfogle offered. Essie continually felt sorry for a little boy with such a mouthful of a last name. She guessed Steven’s meek demeanor came from endless teasing.

“That’s one kind of discipline, yes.”

“God spanked somebody?” Steven seemed scandalized at the idea. “Wow, I bet God hits really hard.” Essie wondered if Steven even realized he was rubbing his backside protectively. Which made her wonder if Steven had considerable personal experience. Did people still spank their kids?

Would she ever spank Josh? It seemed hard to imagine. She couldn’t fathom doing anything like that to her son. Then again, when Decker took the paper whale lovingly prepared for him, crumpled it without a moment’s hesitation, and threw it straight into Steven’s face—hard—Essie could see where a spanking might have its uses.

Well, she’d taken on this class as a chance to see what young boys were really like. Oh, Essie, she chided herself, when will you realize it isn’t always great when you get what you pray for?

“God has never spanked someone, Steven. He— Decker, uncrumple that whale right now, you’re going to need it in a minute. And say you’re sorry to Steven. Nobody throws anything at anyone in this class. God’s so smart, He can find different ways to let us know we’ve not obeyed.”

“I still like the whale guts,” said Peter, obviously disappointed that a stint in whale innards wasn’t in his immediate future. “I bet they smell really gross.”

The suggestion sent the boys into a flurry of stinky adjectives, each in a full-out competition to find the grossest possible description for how bad whale guts would smell. How can I hope to teach obedience here, Lord, when I can’t get past the stinky whale guts?

Just when she thought she could restore order, Peter remembered the lyrics to “Gobs and Gobs of Greasy Grimy Gopher Guts,” a revolting camp song Essie was horrified to discover had still survived even from her childhood. Within seconds all decorum was lost. Essie stood up as fast as her thirty-one-year-old knees would allow, bellowed out a menacing, “Settle down!” in her most authoritative voice and flicked the light switch. It sent the room into darkness.

That shocked ’em. All noise and movement stilled.

“When I turn these lights on, I want everyone to pick up their paper whale and come back quietly to the table. Okay?”

A few whimpered “Okay” s signaled her return to superiority.

“Now,” Essie said in a calm voice as she turned the lights back on, “I want each of you to think about something that you know you should do, but is hard. Something that you know you have to do, but you don’t always want to do. Those things are like Jonah’s trip to Ninevah. We’re going to write those things on your whales. Raise your hand when you have an idea of what to write, and I’ll come help you.”

Peter’s hand shot up first. “I hate getting my allergy shots.”

Essie nodded in agreement. “That’s a good example. It’s no fun, but you know you’ll feel better when you get them, right?”

“Yep, but they hurt.”

Essie wrote “allergy shots” in large letters on Peter’s whale. “When you get them, you can remember that you’re being obedient, and doing what you need to, even though it’s tough. God is very happy when we do obedient things like that.”

Soon the other boys chimed in with their ideas. “Practice piano.” “Be nice to my new baby sister.” “Go to bed.” And a host of other examples until one little response gave her pause.

“Like my new stepmom,” said Alex Faber quietly. “She’s my third stepmom,” he added, kicking his chair with his foot over and over. “I don’t like her. And I don’t think she likes me very much.”

What do you say to something like that?

“It’s hard to be the new person,” Essie responded. “It’s hard to get used to new people. What makes you think your stepmom doesn’t like you?”

“She said so.” Alex kept kicking the chair.

Oh, my.

“I wonder if that’s really true, Alex. Grown-ups have a funny way of saying things sometimes that little boys don’t always understand.” Essie squatted down beside him, warning her knees to cooperate in the name of human compassion. “Can you remember what she said?”

“Well—” Alex took his crayon and began drawing swirly circles on his whale as he talked. “She was talking to Dad at night. I wasn’t s’posed to be up, but I was thirsty so I got a drink and I heard them talking down the hall. You know, in Dad’s room. Vicki—that’s her name, Vicki—didn’t have kids before she married Dad. She was telling him how she didn’t like being a mom so quick.” Alex looked at her with hard eyes. “But she’s not my mom. My mom’s in Minnosoda now.”

“That’s hard.”

“Vicki doesn’t now how to make peanut butter sandwiches or play Uno or do any mom stuff. My sister calls her Icky Vicki. That’s when Vicki gets all mad and locks herself in the bathroom and tells me to go play outside.”

Essie didn’t think it would be wise to admit that she’d have liked to lock herself in the church ladies’ room a couple of times in the last few Sundays.

She took Alex’s hand, stilling the flow of crayon swirls for a moment. “You’re right, Alex, that is a hard thing. And God would want you to learn to like Vicki. And I think He’ll help you if you ask Him.”

Alex raised an eyebrow. “I dunno.”

“I do. Every family’s got an Icky Vicki. Someone who’s hard to like. But sometimes, the Icky Vickies turn out to be the nicest people if you just give them a chance.”

“Yeah,” offered Justin with sudden enthusiasm. “I thought my Uncle Arthur was really boring until he showed me how he can take his teeth out. All of ’em.”

That brought a chorus of approving oohs and aahs—the gross-out factor of extractable teeth was a sure-fire hit with this crowd.

“Justin’s right. People surprise you.” Essie pulled the Children’s Picture Bible off the shelf behind her where it lay open to the Jonah story. “Jonah thought the Ninevites were a whole city of Icky Vickies. He didn’t want to go teach them to act better. He didn’t want to care about them one bit. But God wanted him to care, and to go there. And so, when he did, the Ninevites changed their icky ways and Jonah learned it’s a good thing to be obedient to what God wants.”

And what do you know, those tiny faces actually registered understanding! Little heads were actually nodding.

If Jonah could work with the Ninevites, maybe there was a shred of hope for the Doom Room.

Chapter 4

How Many is the Norm?

Josh wailed every single moment of his doctor visit. This morning’s fever had called a halt to any hope of Josh’s grumpiness being “just teething.” Essie was barely conscious. She couldn’t remember if she’d brushed her teeth yet this morning, so she tried to smile for the doctor without opening her mouth. She tried to look like an intelligent member of the human race, even though she was feeling pretty much like an amoeba.

“Yes, there, Master Walker. That’s one whopping ear infection you’ve got. Both ears, too. Overachiever, I see.” Dr. Martin was trying to put a good spin on things. The man could even be called cheerful. But to Essie right now, twin ear infections sounded like the end of the world.

It must have shown on her face. Dr. Martin walked over and returned screeching little Joshua to her arms with an understanding smile. His appearance and demeanor were so completely, perfectly “doctorish,” that the guy belonged on television. “You’ll be amazed,” he commiserated, “what a little pain medicine will do for the guy. Half an hour, a couple of squirts of pink stuff and he’ll be snoozing in no time.”

“Could I have that in writing?” Essie whimpered.

“Next best thing,” replied Dr. Martin, scribbling off a set of prescription notes. “May I introduce you to your new best friend, amoxicillin? You’ll be very well acquainted by the end of the year. There are two kinds of babies in this world. The kind who hardly ever get ear infections, and…the other kind.”

“Josh is an ‘other,’ isn’t he?”

“I could lie, but you look like the kind of person who prefers a straight story.”

Essie juggled Josh onto her shoulder, which settled his wailing down into a low-grade, pitiful moan. “And the straight story is I’m going to see a lot of amoxi-whatever.”

Dr. Martin touched her shoulder. “It does get easier. When he gets old enough to have good control of his hands—which should be soon—he’ll grab at his ears and you’ll catch on before it gets full-blown awful.”