Полная версия:

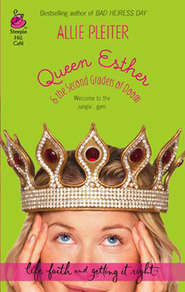

Queen Esther & the Second Graders of Doom

PRAISE FOR BAD HEIRESS DAY

“Delightful and clever, this first novel is worth reading.”

—Library Journal

“Pleiter’s inspirational debut…reflects the true meaning of faith and family. Characters learn to trust God’s goodness and provision even when things appear hopeless.”

—Romantic Times BOOKclub

“Bad Heiress Day is a heartwarming and soulful book for cold winter nights…. Darcy and the secondary characters are warm and real, and this book will not let you go. This is a top-notch story for all of us, and brings to light some of life’s problems and the surprising answers God can guide us to.”

—Romance Reviews Today

PRAISE FOR ALLIE PLEITER

“With humor, wisdom and lots of practical ideas, Allie encourages us to renew our commitment to the high and holy calling of motherhood.”

—Cheri Keaggy, Christian recording artist, on Becoming a Chief Home Officer

“Whether you’re desiring to learn how to apply your business skills to the business of parenting, or wondering why and how fancy underwear can help your mothering, Allie Pleiter draws you the perfect word pictures.”

—Charlene Baumbich, bestselling author of the Dearest Dorothy series, on Becoming a Chief Home Officer

Queen Esther & the Second Graders of Doom

Allie Pleiter

www.millsandboon.co.uk

To Christopher John Pleiter

My Second Grader of Delight

And

To

Anyone

Anywhere

Who’s ever taught

Anyone under ten years old

And lived

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Some books just come to you. The Doom Room and its burping crashed into my imagination one afternoon and simply refused to leave. Those are the books that are joys to write, because it is like unwrapping a gift of many layers—your efforts are filled with ooohs and aaahs as you discover what it is you’ve been given.

First, thanks should probably go to my own son, CJ, who was in second grade when his imaginary counterparts invaded my life. I must emphatically state that none of the antics portrayed in this book were from CJ’s actual second-grade existence. Some, however, come mighty close. Any mother of any second-grade boy anywhere will attest to the universality of bathroom humor, bug fascination, airborne objects and the ability to start a tussle in seven nanoseconds. Still, son of mine, you remain as joyful as you are jumpy, and much of Esther’s experiences comes from my own journey of motherhood—including Josh’s non-stop teething. It seems like all too soon we’ll be marching those pearly whites to the orthodontist….

The rest of my family, even if not so accurately depicted, shoulder the burden of living with me during the writing process. For that I will forever be grateful.

Rachel Young, my own personal New Jersey shot-put champion, served not only as a sparkle of inspiration, but also my resident expert on the athletic details. Any botching of the details is purely my own fault. Caroline Wolfe assisted me in several of the medical details—how many friends can help you pick out the perfect annoying geriatric female ailment?

I’m continually grateful to the team of professionals that keeps me on the bookshelves. My editor, Krista Stroever, always knows just when to let my wacky sense of humor fly, and when to…ahem…rein it back in. My agent, Karen Solem, continues to be the wisest of counsel in this wackiest of worlds that is publishing. Add those fine experts to the high-octane fuel of mocha lattes and Skinny Cow ice cream bars, fold in one kitchen counter and one laptop computer, and you’ve pretty much got the Allie Pleiter production mechanism.

And, as always, I’m grateful to the God who made me, wackiness and all. Who else but our Lord could create the marvelous surprises that have filled my life and gifted me with such wonderful stories? I am truly, abundantly blessed.

Blessings to all,

Allie Pleiter

Contents

Chapter 1: Of Salt Air and Soy Sauce

Chapter 2: Zacchaeus Was a Wee Little Man…

Chapter 3: Stinky Whale Guts

Chapter 4: How Many is the Norm?

Chapter 5: The Box Marked “Those”

Chapter 6: Play to the Strengths

Chapter 7: And on Some Sunday Afternoons…

Chapter 8: The Downpour of Demands

Chapter 9: Attack of the Ph.D.

Chapter 10: The Myth of Just Watching

Chapter 11: Thou Shalt Never, Ever, Ever!

Chapter 12: Reluctant Coffee to Go

Chapter 13: On the Verge of Pop-icide

Chapter 14: The Family History of Airborne Produce

Chapter 15: Just When You Thought it Was Safe To Go Back in the Kitchen…

Chapter 16: Endless Opportunities for Bad Behavior

Chapter 17: Something Bigger To Think About

Chapter 18: The Thanksgiving That Wasn’t…

Chapter 19: And the Victory Goes to…Whom?

Chapter 20: World War Three and the Base-Level Bailout

Chapter 21: Fighting the Undertow

Chapter 22: Deck the Halls

Chapter 23: Athletic Intuition

Chapter 24: The Problem with Queen Esther’s Realm

Chapter 25: Heroics

Chapter 26: Life’s Major Moments

Chapter 27: The Celebration of Bible Heroes

Discussion Questions

Chapter 1

Of Salt Air and Soy Sauce

Essie burst into the room.

Well, that wasn’t unusual—Essie always burst into rooms. It was the look on her face, though, that made Doug put down his hacksaw. It wasn’t very often he saw his wife in a state of panic.

“Essie?”

She groped for words. It didn’t seem to be about Josh: he was right there, tucked baby-perfect into her elbow and chewing on her knuckle, looking as content as a five-month-old teething baby could. Staying in the church nursery during Sunday school obviously hadn’t done him any bodily harm. The walk home perhaps? Had something happened then?

“Promise me!” she blurted out finally.

Doug stashed the saw in its proper drawer and began walking toward Essie to take Josh. “Promise you what?”

“Promise me Josh will never make bathroom jokes, or think crawling under the sanctuary pews is cool, or try to blow Kool-Aid out his nose because he was dared to, or draw the Apostles having a belching competition on his gospel lesson papers—promise me!”

Doug tucked Josh onto his shoulder, feeling his shirt dampen. His new son seemed to be a constant source of saliva. “Slow down, Essie….”

Which was useless, since Essie had now begun to pace the tiny workshop they’d carved out on the back porch of their San Francisco apartment. “Promise me he’ll never see who can say booger ten times fastest, or bark like a puppy for ten straight minutes while someone’s trying to teach him about forgiveness, and that he will possess the seemingly rare ability to sit still for thirty seconds, and that he won’t turn into one of them!”

Doug wasn’t sure there was a safe response to that. He tried to catch Essie’s hand as she paced the short length of the deck, but she slid out of his grasp. She turned and crossed the length again, tugging at her ponytail. She looked like she had another hundred such laps in her.

“They’re animals,” she said to no one in particular. “They’re little beasts in tiny khaki pants and itty-bitty loafers. They couldn’t have been raised by humans. They’re animals.”

“They’re second-grade boys. That’s pretty close to animals in my book.”

“No.” Essie turned to him, eyeing him like a biology specimen. “These aren’t normal boys. Men who run companies and drive school buses and file tax returns don’t start out like this. Mobsters start out like this, not nice boys.”

“You just had a bad day.”

“You know,” she replied as she rubbed at a marker stain on the cuff of her shirt, “I thought that. Last week. But this week was just the same. They’re lunatics, these little boys. It’s like trying to teach a band of chimpanzees on a sugar high.”

She stopped pacing and leaned her body back against one of the support columns. Strands of curly hair had escaped her ponytail, and she pushed them aside with an annoyed gesture. “I don’t why I ever let Mark-o talk me into this.”

Doug offered Josh a knuckle, wincing as the tiny edge of a new tooth made itself known. “You were excited about this. Essie, you’ve always been great with kids. You’re great with Josh. You were voted Teacher of the Year before we left New Jersey. You can do this.”

She turned her gaze out over the alley, away from him. “No one in the hallowed halls of Pembrook High School ever called me Mrs. Poopy-head.”

“Well, not to your face, maybe…”

“Doug…”

“Okay, okay.” He came up behind her and kissed one shoulder. “So they’re a rough crowd. And they lack certain social skills. That doesn’t make you a bad teacher. From what I remember of second grade, ‘poopy-head’ is a compliment.”

A tiny laugh escaped her lips. “So this is like kindergarten, where if I hit you it means I like you?”

“Not exactly. By second grade the ‘cootie factor’ comes into play. Look, Essie, Mark’s under a lot of pressure from those private-school-types to get things right. He wouldn’t have asked you to teach at his church if he didn’t think you’d do a great job.”

“I bet he’ll get calls today. Mrs. Covington’s gonna pop right out of her Guccis when she sees her son’s ‘Burping Apostle Peter.’ Where do those little minds dream up this stuff?”

“You were expecting them to line up and sing ‘Jesus Loves Me’ in harmony? Don’t you remember second grade?”

She rested her head against the pillar. Josh reached out a chubby hand to grasp at his mother’s curls, now within reach, and tried stuffing one in his mouth. Essie winced at the pull and turned to face them. “I thought I could handle them, Doug.”

“You can. You’re just going to have to work a little harder than you thought to pull it off.”

“I don’t know.”

“I do. The Essie Walker I married can’t be conquered. You could shot-put one of those kids across the room if you had to, and I bet they know it. Perhaps during next week’s lesson you could mention that you are the New Jersey state champion.”

“These boys don’t even respect the laws of gravity. They’re not going to respect the 1993 New Jersey state shot-put title.”

“I don’t know,” said Doug, breathing in the particularly wonderful scent of his wife’s neck. “It goes a long way with me.”

“You,” she said, her voice pitching a bit higher when he kissed her in just the right spot, “don’t count.”

“Joshua and I are insulted at that remark.” Doug pulled away in mock indignation.

“I’ll make it up to you.”

She leaned in to kiss him, her hair glinting in the early afternoon sunlight. Doug inhaled in sweet expectation.

Only to hear his son fill his diaper. Enthusiastically. And then snort in manly satisfaction.

Doug rolled his eyes. “Boys and their bodily functions.”

Essie sighed. “I’ll change this one.”

“No,” Doug countered. “I think you’ve had enough of male physiology for one morning. I’ll take this one. There’s some pink lemonade in the fridge. I’ll take care of Mr. Toxic Pants here and meet you back on the deck chairs.” He used his free hand to nudge her shoulders toward the kitchen.

Essie didn’t argue. Which could only mean those boys really had been beasts.

The second-grade boys’ Sunday school class at Bayside Christian Church was proving to require stamina of Olympic proportions. Two weeks into the job—no, Essie corrected herself, into the ministry—and she was up to her earlobes in doubt. She was a fine teacher, but try as she might, she could not get the upper hand with this squirrelly class. Essie was still shaking her head as she closed the fridge door and returned to the porch to sink into an Adirondack chair.

She loved these angled wood chairs. They barely fit on the deck, and their New England rustic charm clashed with the jazzy Euro-style that was San Francisco. Ah, but Essie wouldn’t give these chairs up for the world. They were home. Barbecues in the backyard followed by walks to the beach. They were morning coffee cups steaming into the salt-laden air, they were lemonades on the lawn when it was hot and sticky. Essie let her head fall back against the wood and tried to conjure up a New Jersey Sunday from the scents that lingered in the grain. Of a life where she knew what to do and where she fit in. It worked a bit—just the hints, the barest fragments of a Jersey shore summer came uncurling out of her memory. Had they really been in San Francisco for a month? Had she really jumped straight from the shores of one ocean to the shores of another? The tang of soy sauce from the sushi bar on the corner floated in on the breeze as if to confirm her thoughts.

Josh’s post-baby-wipe coos came through the doorway. “Wow!” commented Doug, wrinkling his nose as he tucked Josh back onto his shoulder. “Can all that come out of one baby at one time?”

“Please…not one more shred of conversation about body functions. Even from you. Even about Josh.”

Doug chuckled as he eased himself and Josh into the other chair. “Deal. Hey, look, Essie, you’ve done your tour-of-combat duty for this week. Josh will practically sleep through couples’ Bible study tonight, it’ll all be grown-ups, and you’ve got six days before you even have to think about apostolic burps again. Just let it go for now.”

Esther drank her lemonade, wishing it was as easy as that. “I wish you were right, but I said I’d come to their Christian education committee meeting on Tuesday morning. They even promised to get one of the committee member’s daughters to sit for Josh if he got antsy so that I could attend. I’m gonna get grilled, I know it.”

“That’s your game-face talking, Essie. They are not going to hold up score cards to rate your first two weeks with that class.” He turned to look at her. “Did you ever stop to think that Mark invited you so you’d get a chance to meet some of the other mothers in the church? To help you make a few friends out here? Did you consider that?”

“No.”

“Well, you ought to. Your brother’s no fool. He’s smart enough to know that if we had to count on the finely tuned social graces of my coworkers at Nytex, we’d never meet a soul. Software engineers don’t have a geeky reputation for nothing. I’m living in the land of the pocket protector here.”

There was just a bit of an edge to his last remark, and Essie realized she hadn’t thought about that. She’d just assumed that Doug had grafted himself into a ready-made circle of friends. She imagined him lunching with buddies and rehashing baseball games at the watercooler. They’d made this cross-country move for her more than for him—it was purely God’s grace that he was able to land a job so easily after they decided to join her brother out here to help with her aging parents. Sure, he’d never once griped about moving to San Fran, but that didn’t mean he was enjoying it. Doug wasn’t the kind of man who complained. Essie wanted to whack herself on the forehead for being so self-centered.

“Office a little geeky this week?” She’d never even thought to ask before now. Nice wifely behavior. Way to be that strong support system, Essie.

Doug’s sigh told far more than his words. “A bit. I’m fitting in.” After a long pause he added, “Slowly.”

“We did the right thing, didn’t we? Made a good choice?”

Doug turned immediately and caught her hand on the armrest next to his. “Yes. Essie, I don’t doubt it for a second. You know I agreed to this fully, of my own geeky free will. My parents in Nevada aren’t so far away now—we’re nearer to both our parents.”

“Why isn’t it easier?” Essie was amazed at how much the words caught in her throat. Josh stared at her, his wide gray eyes beaming love out from their perch on Doug’s shoulder. He made a gurgling sound and waved a tiny fist in the air. She caught it, and reveled anew in how his minute grasp fit perfectly around her finger. She’d wanted to be a mother since forever. No book or magazine, though, did justice to how just plain hard it was. She’d never felt further out of her element than she did this past month.

“Let’s see,” said Doug, pushing his glasses up on his nose. “New job, new city, new baby, new home, new weather—well, okay, that’s more of a fringe benefit. There’s a hunk of adjustments in that list. I think we’re doing pretty good. Most of my programs don’t even adapt this well—and I design relocation software, remember?”

“Can you design a—what do you call it? An integration program—for one small family? Make a button for me, Doug. One I can push and make all the uncertainty go away.”

Doug chuckled. “I did, sort of.”

“No kidding? Where is it?”

Doug held up the cordless phone he’d evidently brought onto the deck with him. “Pepperoni pizza, really thin, New York-style. Coming up.”

“I’m liking this.”

“A guy at work—one of the less geekier ones—recommended a place. His uncle moved here from Manhattan, and called it his ‘relocation coping mechanism.’ I’ve been saving its implementation for just such a moment.”

“Doug Walker, I love you.”

He winked. “Nah, that’s just the pepperoni talking. Is this a ‘medium,’ or a ‘large’ kind of day?”

Essie smiled, too. For the first time since she came home. “Do they make an extra large?”

Chapter 2

Zacchaeus Was a Wee Little Man…

She wasn’t supposed to be this nice.

When Essie first spied Celia Covington—and even more so when someone called her “Cece”—she was supposed to fall easily into the well-to-do-nitwit category. The twinset was a dead giveaway. Essie was always suspicious of women who wore twinsets. Those bearing sweaters in pastel colors, and most especially when adorned with a string of tasteful pearls, were to be avoided at all costs.

Essie had her own personal classification system for the branches of womanhood. There were “the ponytails,” which had a subset containing the unpretentious and practical, and another subset of the entirely-too-perky. This could usually be distinguished by height. Not of the woman, but of the ponytail. High ponytails signaled high-level perkiness. Low ones generally denoted practicality.

On another branch of the tree of womanhood sat “the headbands.” There was a certain kind of woman, Essie surmised, who wore headbands. Personality was then telegraphed by the type of headband selected—fabric, tortoiseshell plastic, wide, thin, etc. But it was the well-off, well-bred, well-dressed woman who generally opted for the headband as hair accessory. Or, on rare occasions, the headband became the tool of choice when the practical woman wanted to dress up.

Put a headband and a twinset together, and a smart gal runs quickly in the other direction.

Celia Covington, however, didn’t fit the twinset mold. She passed by the precise corner of pastel-sandaled women who flanked the far end of the table and plunked herself down in the middle, with a heavyset, friendly Japanese woman on her left, and an Hispanic grandmother-type on her right. This placed Celia directly opposite Essie across the rectangular table. Essie had opted for the middle of the table as well, seated next to Mark. As in her brother Mark-o, or as everyone called him, Pastor Taylor.

“You’ve got to be Mrs. Walker,” Celia said, smiling. “David went on and on about you the other day. You’ve made quite an impression on my little monster, and that’s no small feat.” She had an authentic, squint-up-the-corners-of-your-eyes smile that lit up her face. Essie tried not to like her—on account of the headband and all—and failed.

“Please, call me Esther. Actually, call me Essie. Everyone else does.”

“I’m Celia—Cece, actually. David, the little tornado in your class, he’s my youngest. He’s a handful, especially after he’s sat through a Sunday service. There’s only so much patience a roll of Life Savers can buy.”

Well, it was a small headband, after all. And coral isn’t really a pastel. “He’s a good kid. Very creative. I think he really enjoys drawing, and he seems to be rather good at it. I could tell right away that his gray blob on Noah’s ark was a rhinoceros. Most of the other blobs were undistinguishable. And no one else thought to put rhinos on the ark.”

Celia laughed. “That’s David. Always thinking out of the box. My oldest, Samantha? She’s in the nursery with her nose in a book, ready and waiting should your little one get too squirmy.”

Nice lady with babysitter daughter. No, coral is definitely not in the pastel family. “Thanks, but I think Josh is out for the count. You never know, though.”

“Don’t worry. Sam would consider it a treat to tuck a little cutie like that into her arms. Want some coffee?”

Essie sighed. “Oh, you wouldn’t think Josh was so cute if you’d seen him screaming his adorable little head off at two-thirty this morning. Sugar, please.”

“Teething?” Celia called over her shoulder as she walked to the sideboard.

“Like a pro.”

“Have you tried a grapefruit spoon?”

A what? Why would you hand spiky silverware to your newborn? Who actually had one of those? “Uh, no.”

Celia laughed at Essie’s apparent shock. “I know it sounds barbaric,” she said, bringing back the coffee, “but the metal stays cool, and as long as the serrated edges aren’t really sharp, it helps the tooth break through the gum. It’s all that straining against the gum that makes babies crazy. Once the full surface of the tooth breaks through, they settle right down.”

“Really?”

“I’ve got four sets of healthy gums marching their way to the orthodontist to prove it.”

Lean, lovely Celia Covington was way too toned to have birthed four children. Not if Essie’s own lumpy belly was any indication. Still, she had returned from the sideboard with java and cookies, not the spiffy-label bottled water that seemed to be the beverage of choice over in the corner. Those women looked like they’d not touched a cheese-burger since high school. “I’ll take your word for it. But I don’t own one. I don’t even know where you’d get one.”

“Well, you could go to TableSets and pay a ridiculous amount of money for some, or you could stop by Darkson’s restaurant supply just down the block and pick up a half-dozen for peanuts. If Josh is crying as you walk in the door, they might even give you one for free out of sheer sympathy.” She winked as she dipped a cookie into her coffee.

Essie decided that she might want to start liking Celia Covington.

“Now that we solved a few pediatric issues, here,” interjected Mark, looking at his watch, “we need to get started so I can give you ladies as much of my time as I can before my eleven o’clock appointment. Dahlia, do you have an agenda for today?”

Dahlia, who looked like she’d just walked off the cover of a magazine, flipped open an expensive-looking notepad. “Just two items, Pastor, but they’re hefty ones. One—” she held up her substantial silver pen and flicked it like an orchestra conductor “—I want to run down how things are going with Sunday school. It’s been two weeks, and we ought to be able to see the problem areas bubbling up by now.”

Essie gulped. Somehow she just knew this woman had a second-grade boy.

“Second—” the pen bobbed again “—it’s time to start the ball rolling on the Celebration.” That seemed to surprise some of the women around the table. “Now, gals, every January we’re caught scrambling. I know we’re all just getting our feet underneath us with Sunday school for the year, but I can’t help thinking now’s the time to start planning.”

Celebration? Could that be that “little drama thing later in the year” Mark-o mentioned? That thing he distinctly described as “nothing you’ll have to worry about”? She’d taught school long enough to know that any event requiring several months’ worth of preparation could never be classified as “nothing much.” Most especially when parents were in charge. Essie shot a look to her brother out of the corner of her eye. He knew this was just a trial stint. He knew she and Doug weren’t sure they could make it on one income, and that Essie going back to work in the new year was a distinct possibility. Now there was this Celebration thing in the mix? If she did go back to work, Essie was pretty sure she couldn’t handle this on top of it.