Полная версия

Полная версияПолная версия:

The Australian Army Medical Corps in Egypt

We have never wavered from the conviction that any one suffering from venereal disease should be treated by a medical practitioner exactly like any other sick person. In military service, however, an added element makes its appearance in that the soldier by his act has rendered himself unfit, and consequently must suffer some pains and penalties. It is no answer to say that other men have exposed themselves and have not become infected. The fact remains that he has by a deliberate and avoidable act deprived his country of the value of his services. And whilst the doctrine of punishment should not be pushed too far, he certainly should not receive the same general treatment as other soldiers, and the policy of his prompt return to Australia and deprivation of pay was in the circumstances the best one.

In the Venereal Diseases Hospital, Abbassia, the men were well treated. They were well fed, and a certain amount of Red Cross help was given to them.

Many proposals were made which were not carried into effect: for example, placing of the prostitute quarter "out of bounds" and the posting of sentries. It was realised that the immediate effect of this action would have been to drive women to the vicinity of the camps, and that it was impracticable. Another practicable proposal was made, which, however, was not carried into effect – the creation of dispensaries in the vicinity of the prostitute quarter, so that immediate treatment could be obtained. In many camps such dispensaries were established by the medical officers.

The essence of the problem was learnt by a Brigadier-General who visited a number of young educated men in one of the camps, and asked them for their viewpoint on the subject. Their answer was that which every medical officer knows full well: that many men were influenced by the appeals which had been made to them, but that a percentage have indulged in this way throughout their adult life, and intend to continue to do so irrespective of anything medical officers, chaplains, or generals may say to them. It is this fundamental position which every reformer must face. So long as a sufficient number of men determine to adopt this policy, and so long as there is a sufficient number of women prepared to cater for them, the problem of venereal disease will continue to be acute in every country.

The opinion has been expressed elsewhere that the world will not be rendered more or less moral by the abolition of venereal disease, and instruction in the mode of preventing infection should be an essential part of education. Because people are immoral there is no reason why they should acquire gonorrhœa or syphilis. If the lex talionis is to be enforced, the logical way to deal with the matter is to refuse treatment to all the infected, and to let them die or become disabled. But the most thorough-going Puritan shrinks from adopting so terrible a policy. One method or the other, however, must be adopted – there can be no half-way house. And if the decision be in favour of eradicating the disease, it is essential to firmly face and grapple with the problem.

Wassermann TestsThe examination of the cases showed that gonorrhœa was far more common than syphilis, and a series of Wassermann determinations showed that the cases of soft sores did not give a syphilitic reaction in the early stages. Captain Watson of the First General Hospital made a number of determinations in order to try to settle this important point.

The Policy to be AdoptedIn spite of all that was done, 1,344 men were returned to Australia disabled, and 450 were sent to Malta. If a calculation be made of the cost of sending these men to Egypt and back, and of their pay before they were infected, some idea may be formed of the enormous sum of money the Australian Commonwealth wasted on men who were a drag and hindrance to the army machine.

The Government should, on the raising and equipping of a volunteer army, treat it as older countries treat a standing army by issuing instructions to the men.

When the Hospitals left Australia neither officers nor men received instructions, and not until the arrival of Surgeon-General Williams in Egypt was any serious collective action taken. He at once called a conference of medical officers and did what he could to limit the extent of disease.

The governmental action – or lack of action – is unsound, since the man who contracts disease is severely punished, but adequate attempts are not made to prevent him acquiring it. The notable departure made in the case of Cairo was the effort to make the men understand clearly what these diseases meant to them as soldiers and as citizens; to remove temptation from them as far as possible, and with the aid of the Australian Red Cross to give them a reasonable, healthy, and decent alternative. Nothing the Australian Red Cross has done (or is likely to do) is more important than the establishment of the Soldiers' Clubs. Nothing has been more successful or is likely so to redound to the credit of that great institution. And yet, under the new Constitution of the Australian Red Cross, not a shilling can be devoted in the future to such purposes.

Venereal Diseases ConferenceThe following are brief notes of a Conference of senior medical officers convened by Surgeon-General Williams.

Reference was made to the gravity of the problem with which the force was faced. It was estimated that about 1,000 men of the First and Second Australian Divisions are suffering from venereal disease on any one day, and of these a large number are incapacitated from work. The proportions seemed to be much greater than those of other forces, such as the Territorials, in Egypt. The displacement of so large a proportion of men and the ultimate consequence of numerous infections, rendered it necessary to take a comprehensive view of the position, and to endeavour to take some action to minimise the damage done. It was proposed to ask each officer present to furnish the secretary with a general statement of the number of cases treated under their command, specifying them under three headings – syphilis, soft chancre, and gonorrhœa. The information so obtained would form the basis of a report to headquarters. The problem was considered under five headings:

1. Military assistance.

2. Use of prophylaxis.

3. Treatment – general and special.

4. Establishment of convalescent depots – accommodation and position.

5. Ultimate destination of affected men.

1. In what way can the military authorities give assistance?– There are three ways in which they can approach the problem:

(a) They may decide that all areas known to contain brothels are out of bounds.

(b) They can provide adequate military control by military police organised under a competent officer, with one or more junior medical officers to assist him.

(c) That punishment can be inflicted on those men who break bounds and expose themselves to the risk of venereal infection. It might be desirable to reduce the pay of men found in those areas whether suffering from venereal disease or not.

2. Prophylaxis.– Officers were invited to discuss the question whether it would not be advisable to establish prophylactic depots in various parts of Cairo. Men to report immediately after exposing themselves to infection, and by cleanliness and the use of medicaments prevent infection. Circulars couched in plain and sensible language might be issued to the troops, conveying to them a knowledge of the risk they run, and the fact that if infected they will take back to Australia a disease which would reduce their value as citizens.

3. General and Special Treatment.– Suggestions from officers present were invited.

4. Convalescent Depots.– Was it right that the hospital should be crowded out with venereal cases, which demanded very much time and attention from the staffs? If the hospital was placed near the scene of military action the wounded might suffer from the amount of attention required for venereal cases. Most venereal cases required rest in the main, and this could be obtained in convalescent depots.

5. The ultimate destination of the affected men.– Two courses are open: The men may be treated in Egypt, or sent back to Australia.

(a) If they are kept in Egypt and the Australian Expeditionary Force is moved to the front its medical services would be depleted, and medical men of great ability and experience would be left behind to take charge of venereal cases when their services were required at the front.

(b) If on the other hand the Australian and Imperial Government could utilise some ships for the accommodation of these men, those who were cured could be sent to the front, and those who could not be cured could be sent back to Australia at once. But such ships would require special staffing so that the existing units should not be depleted in order to provide staffs.

In the discussion which ensued it was represented that there was a difficulty in placing areas out of bounds, as the brothels would be moved to other areas. Prophylaxis was regarded as most important. Isolation tents could be set apart in the regimental lines where men could be treated on return from leave. Cases of syphilis should be sent to Australia.

The reduction of pay is forbidden by King's Regulations, and although the Minister for Defence in the Commonwealth of Australia authorised such reduction, it is only for such period as the troops are in Egypt.

It was agreed that cases of syphilis should be returned to Australia, as there is no chance in Egypt of treating them efficiently, and even if such treatment were available the men would not be fit for duty for from four to six months.

It was pointed out that at least 100 men left Australia with the First Division suffering from venereal disease.

The chief difficulty seemed to be what venereal cases would ultimately be of service to a fighting line, and to properly arrange for them during convalescence; in other words, when and how men considered unfit for further service should be returned to Australia. Officers were asked to recollect that the future of these soldiers was to be considered and the part they would play in civil life. In the American Navy unbounded shore leave had been given, and had some effect in checking the disease. In the British Navy it was an offence not to report "exposure."

The Soldiers' Clubs are fully described in the chapter on the Red Cross. They were rendered possible by an alliance between the Y.M.C.A. and the Australian Branch British Red Cross. To the Y.M.C.A., who managed them, the best thanks of Australia should be given, for Australians will never fully know what they owe to Mr. Jessop and his assistants. Unfortunately, the Australian Branch British Red Cross subsequently decided that help should be given only to sick and wounded. Although convalescents frequent these clubs, the view was taken – we think wrongly – that Red Cross funds could not be used for their support. We feel sure that when Australians fully understand the matter the decision will be reversed.

CHAPTER IX

THE RED CROSS WORK: ITS VALUE AND LIMITATIONS – ORIGIN IN AUSTRALIA – REPORT OF EXECUTIVE OFFICER IN EGYPT – RED CROSS POLICY – DEFECTS OF CIVIL AND THE ADVANTAGES OF MILITARY ADMINISTRATION – WHAT WAS ACTUALLY DONE IN EGYPT.

CHAPTER IXThe British Red Cross Society, Australian Branch, was founded by Her Excellency Lady Helen Munro Ferguson, wife of the Governor-General of Australia, on the outbreak of war. On previous occasions unsuccessful attempts had been made to found an Australian Red Cross Society. On this occasion the movement was most successful, although many people then (like some people now) were quite unable to understand the distinction between the Red Cross movement and military administration.

The Red Cross Society in Australia undertook the collection of funds for immediate transmission to the British Red Cross Society for prompt use in the field. Branches were formed in each State and committees were formed by the wives of the various governors. Thus a rough-and-ready arrangement was made prior to the adoption of a constitution. It was considered far more important to do the work than to waste time holding meetings and devising a constitution. Those who could not afford to give money were invited to make clothing or to contribute articles of various kinds. Specifications of the clothing requisite were given, and patterns furnished so that it might be readily made on approved design. It is not too much to say that the majority of the inhabitants of the Continent were soon engaged in some way or other in helping the Red Cross movement. The ball-rooms of the respective Government Houses were used as depots. The depot at Federal Government House, Melbourne, was an excellent model. People were invited to send their donations irrespective of their number or their kind. These were received and receipted, and were then sorted into bundles of similar articles by lady volunteers. They were then placed in cases by volunteer packers, mostly experienced men from various warehouses, and were finally dispatched to Europe as opportunity offered.

The arrangement of these details fell largely on the Council and Secretary of the Branch (one of us, J. W. B.) in Australia acting under the direction of the President, Her Excellency Lady Helen Munro Ferguson. Very great difficulty was experienced in finding space in merchant ships for the conveyance of the goods. Space was found on the transports, but there was not the same security for delivery. In addition the hospitals of the transports were provided with such equipment as the officers commanding desired.

When, however, the Lines of Communication Units were ordered to Egypt, another problem arose, and the Australian Red Cross Society decided to properly equip these units both with money and goods. For this purpose £10,000 was set aside and forwarded to London. It was handed to the British Red Cross Society and kept available for the officers commanding the five hospitals, the requisite sum of money to be allotted to them by Surgeon-General Williams, C.B., the Director of Medical Services in Australia, who had proceeded to Europe. At the time it was supposed that these five hospitals were proceeding to France. In addition large quantities of goods were available at the British Red Cross Society in London, and large quantities of goods were given to the several hospitals for dispatch with their equipment. When, however, the hospitals were sent to Egypt a new situation arose. There were many other medical units in Egypt besides the hospitals. There were the Field Ambulances and the Regimental Medical Officers, and Surgeon-General Williams regarded them as equally worthy of assistance. On his arrival in Egypt at first, in December, and subsequently in the middle of February, the scope of the British Red Cross, Australian Branch, in relation to Australian troops had extended far beyond the original intention. The action taken is described in the following report sent to the President and members of the Council, British Red Cross Society, Australian Branch, on my resignation (Lieut. – Col. Barrett) from that body on September 9, 1915. I did not at any time receive any instructions from Australia, and acted in the manner which seemed best after consultation with local authorities.

REPORT ON THE WORK OF THE AUSTRALIAN BRANCH BRITISH RED CROSS IN EGYPT, FROM MARCH TO SEPTEMBER 3, 1915 By James W. Barrett, Lieut. – Colonel, Lately Executive Officer, Australian Branch British Red Cross SocietyReport presented to the President and Members of the Council of the Australian Branch British Red Cross SocietyThe First Australian General Hospital arrived in Egypt in January 1915. I was associated with it as Registrar and Oculist and had nothing to do with the Red Cross movement beyond assuming responsibility for any Red Cross goods which belonged to the Hospital.

When leaving Melbourne Colonel Ramsay Smith was informed that there would be room for 100 tons of Red Cross goods in the Kyarra. When, however, the Kyarra reached Melbourne her holds were full and no Red Cross goods were taken on board. There were consequently not any Red Cross goods available at No. 1 Australian General Hospital for some considerable time after arrival in Egypt.

Surgeon-General Williams, C.B., arrived in Egypt in the middle of February, and at once proceeded to organise the Red Cross movement. He had been entrusted with £10,000 which was to be expended by the officers commanding medical units according to the plan set out later. He at once took action, and money was distributed to a number of hospitals and medical units. This distribution was of the utmost service.

When Red Cross goods began to arrive in Egypt he sought a suitable store. Finding nothing in Cairo at a reasonable price, he established a store in the basement of the Heliopolis Palace Hotel, No. 1 Australian General Hospital, for which, of course, no rental was charged. The store was placed under the immediate charge of the Orderly Medical Officer, Captain Max Yuille, and under my general direction. The distribution of money and collection of goods from ships was effected by General Williams through his own office in Cairo.

General Williams left for London on duty on April 25, leaving me in charge of the Red Cross work, and leaving his Warrant Officer, Mr. Drummond, in his office to continue the collection of goods and the clerical work.

Soon after he had left, the crisis of May and June took place. Wounded and sick were poured into Cairo on a scale probably never known or equalled before. There have been occasions on which a much larger number of men have been wounded, but probably never any occasion in history in which so many wounded men have been handled in so limited a space. Fortunately preparation had been made by the D.M.S. Egypt, Surgeon-General Ford, D.S.O., and the D.M.S. A.I.F., Surgeon-General Williams, C.B., who instructed the O.C. First Australian General Hospital, Colonel Ramsay Smith, and myself as registrar to take over extra buildings and provide equipment. It was this action which prevented a disaster, and whilst not strictly a Red Cross matter was greatly aided by Red Cross equipment.

During this crisis I was instructed by the D.M.S. Egypt, Surgeon-General Ford, and the O.C. Australian Intermediate Base, Colonel Sellheim, to visit various hospitals in Egypt – both in Alexandria and the provinces – to interview the Australian wounded and supply all reasonable comforts. In accordance with this order, money and goods, either or both, were sent to various hospitals as set out in the various tables.

It so happened that the British Red Cross Society possessed neither money nor goods at the inception of the crisis, and the authorities were profoundly grateful for the help which the Australian Branch afforded. The British Red Cross, Egyptian Branch, at a later stage received large supplies of money and goods which were freely distributed. The fact that goods could be obtained from the British Red Cross Society, Australian Branch, soon became known, and many requisitions were received. The list of goods available was widely circulated and in no instance was the requisition of any Officer Commanding not complied with. It was always completed to the extent of our resources. Periodical reports of the work done were prepared and forwarded to the President of the Australian Branch British Red Cross Society, Melbourne.

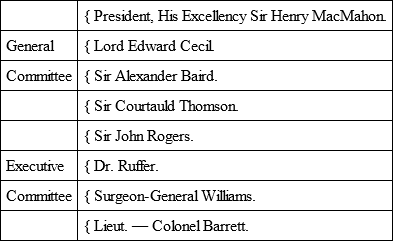

Whilst the work was at its height a message from Australia reached His Excellency Sir Henry MacMahon, in consequence of which two Committees were formed on June 3, 1915 – a General Egyptian Committee and an Executive Committee.

The members were:

Sir Courtauld Thomson is the Commissioner in the Mediterranean for the British Red Cross Society, and Sir John Rogers and Dr. Ruffer Deputy Commissioners in Egypt.

Surgeon-General Williams and Lieut. – Col. Barrett were appointed members of the Executive Committee of the British Red Cross Society in Egypt.

There was no amalgamation of the two branches, but by this arrangement each was kept informed of the activity of the other and wasteful overlapping was avoided.

Members of the General Committee investigated the work of the Australian Branch, were consulted in matters of policy, and received and investigated any complaints. They were most helpful.

General Williams returned to Egypt on June 21, made a tour of inspection, and visited the Australian wounded. He reported to the Government, and finally left for London on duty on June 29. On this occasion he took with him his office staff, and consequently the administration fell largely into my hands.

On July 13, however, I learned by cable from Australia that two Commissioners had been appointed in terms which seemed to place them in entire control of the Red Cross movement.

As it was desirable that other medical officers should be associated with the movement. Colonel Ryan, Colonel Martin, and Lieut. – Col. Springthorpe were invited by His Excellency Sir Henry MacMahon to join the Executive Committee.

Mr. Adrian Knox, K. C., the first of the Commissioners, arrived in Cairo on August 11, and the second Commissioner, Mr. Brookes, reported on August 27. I endeavoured to help them in every way that was possible, and finally asked to be relieved of the work on September 9, expressing my willingness, however, to continue to aid in any way they desired. My relationship to them has been cordial, and I am very glad if I have been able to be of any assistance.

I now propose to deal with the operations of the Society under various headings:

1. Finance.– The original fund in the hands of Surgeon-General Williams was operated upon by him in London, in Malta, and in Egypt. It was only in Egypt that I was concerned with it, and to a limited extent. It was most helpful, and great service was rendered during the crisis by the prompt distribution of money.

When the General Committee, of which His Excellency Sir Henry MacMahon is President, was formed, separate funds were forwarded to him in response to a cable from me indicating that more money was wanted. I suggested the supply of another £10,000, but when, on July 9, £18,000 had been received it became obvious that operations were contemplated on a more extensive scale than had hitherto been thought necessary. I have prepared a summary of the amounts distributed to medical units from both funds, and given an account of the method adopted.

The Red Cross Society originally intended that £10,000 was to be expended by the officers commanding medical units, and General Williams embodied the direction in the following circular, to which I subsequently added a memorandum in further explanation of new conditions which had arisen.

Australian Imperial ForceReceived from Surgeon-General W. D. C. Williams, Director Medical Service, A.I.F., the sum of – stg. to be utilised and accounted for by me in terms of Circular Letter No. E 1/15, dated 13-2-15.

– O.C.Place —

Date —

Australian Imperial ForceCircular Letter No. E 1/15.

O.C.,

1. Forwarded herewith the sum of – stg. to be expended by your authority and direction on such articles as you may consider requisite for the general improvement of equipment, stores, or other items which in your opinion will conduce to the general well-being and comfort of the patients in hospital under your command.

2. Attached receipt forms to be signed in duplicate and returned to me.

3. When three-fourths of the amount allocated to you has been expended, you will furnish this office with expenditure vouchers in duplicate. This will enable me to keep the High Commissioner informed as to how the moneys are being spent, and to arrange for further grants if considered necessary.

Surgeon-General,Director Medical Services, A.I.F.[Copy]May 20, 1915.O.C.

Govt. Hospt.

Tanta, Damanhour and Shebin el Kom.

1. I enclose herewith cheque for {£50 £25 £25} to be expended in terms of the Circular Letter attached. Will you please sign the accompanying receipt in duplicate and oblige.

2. It is not desired that the expenditure of the money should be restricted to Australians, as such a course would, I think, in a hospital be impracticable and undesirable. If, however, this is used for all the Allied troops under your care, then the next instalment which may become necessary might well be provided from the "Military Hospitals Fund" or the "Egyptian Red Cross Fund."