скачать книгу бесплатно

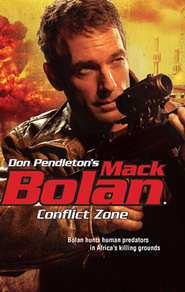

Conflict Zone

Don Pendleton

Nigeria is rich in oil, drugs and blood rivals–on both the domestic and international fronts. Mack Bolan's ticket into the chaos is a rescue operation involving the kidnapped daughter of an American petroleum executive.Her safe but violent return brings the warrior to phase two of his scorched-earth campaign against the escalating guerrilla violence in this country's delta state. Knowing that confused enemies mount ineffective defenses, Bolan launches multiple precision strikes, luring into the open hostile tribal factions vying for control of the oil fields. At the same time Chinese and Russian agents are cutting themselves in on the region's untapped fortune in oil. It's the kind of blood-and-thunder mission that Bolan fights best, the kind of war that keeps him in his element long enough to defeat the enemy and–with luck–get out alive.

“Change of plans,” Bolan snapped. “Follow me.”

The Executioner turned and raced with the hostage toward a line of vehicles. A shot rang out behind them, followed instantly by a dozen volleys.

Turning, Bolan raked the compound with a long burst from his Steyr AUG. Mandy fumbled with her pistol, getting off several shots, yelping as a round stung her palm.

Reaching the motor pool, Bolan chose a jeep at random, slid behind the wheel and gunned its engine into snarling life as Mandy scrambled into the shotgun seat.

“Hang on!” he said, flooring the gas pedal, barreling through the middle of the camp to reach the access road—and freedom.

Conflict Zone

Mack Bolan

Don Pendleton

www.mirabooks.co.uk (http://www.mirabooks.co.uk)

Pure good soon grows insipid, wants variety and spirit. Pain is a bitter-sweet, which never surfeits. Love turns, with a little indulgence, to indifference or disgust; hatred alone is immortal.

—William Hazlitt

“On the Pleasure of Hating” in

The Plain Speaker (1826)

I can’t stop hate. No one in history has come close, so far. But I can interrupt atrocities, beginning now.

—Mack Bolan

“The Executioner”

For Corporal Jason Dunham, USMC

April 14, 2004

God Keep

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

CHAPTER NINETEEN

CHAPTER TWENTY

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE

CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO

CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE

PROLOGUE

Esosa Village, Delta State, Nigeria

David Uzochi had been fortunate. He’d left home an hour before dawn to hunt, and he had been rewarded with a herd of topi when his ancient Timex wristwatch told him it was 8:13 a.m.

With game in sight, it came down to his skill with the equally ancient .303-caliber Lee-Enfield bolt-action rifle he carried, its nine-pound weight as familiar to Uzochi as the curve of his wife’s hip or breast.

He’d nearly smiled, thinking how pleased Enyinnaya would be when he brought home the meat, but he had caught himself in time, before the twitch of his lip or glint of sunlight on his white teeth could betray him to the grazing topi.

His first shot had been the only one he needed. As the other topi dashed away frantically to save themselves, Uzochi had been swift to clean his kill. There was no time to waste, when flies appeared to find a wound almost before the skin was broken, and the brutal sun began corrupting flesh before the last heartbeat had time to fade away.

The four-mile walk back to Esosa was a good deal shorter than his outward journey, since he was no longer seeking game, and he wouldn’t rest once along the way, despite the forty-something kilograms of flesh and bone draping his left shoulder. Uzochi drew a kind of buoyancy from his success, doubly thankful that he had meat enough to share with some of his neighbors.

The sound of the explosion made him break stride, pausing long enough to lock on its apparent point of origin.

The pipeline. What else could it be?

He cursed the Itsekiri bastards who were almost certainly responsible. Their war against pipelines and the pumping fields meant less than nothing to Uzochi, but he understood the Itsekiris’ hatred for his people, the Ijaw. And if this raid had brought them near Esosa…

Any doubt was banished from Uzochi’s mind when he saw the first black plume of smoke against the clear sky. The pipeline passed within a thousand yards of his village, and how could any Itsekiri cutthroat neglect such a target when it was presented?

Uzochi began to run, jogging at first, until he stabilized the topi’s deadweight to his new pace, then accelerating. He couldn’t sprint with the topi across his shoulders, and he never once considered dropping it.

Whoever managed to survive the raid would still need food.

Tears blurred his vision as he ran, thinking of Enyinnaya in the Itsekiris’ hands. Perhaps she’d seen or heard them coming and had fled in time.

A distant crackling sound of gunfire, now.

The sudden pain he felt was like a knife blade being plunged into his heart. It didn’t slow him, rather the reverse, but in his wounded heart David Uzochi knew he was too late.

Too late to save the only woman he had ever loved.

Too late to save the child growing inside her.

But, perhaps, not too late for revenge.

If he’d forgotten where the village lay, Uzochi could have found it by the smoke. When he was still a half mile distant, he could smell the smoke and something else. A stench of burning flesh that killed his appetite and made his stomach twist inside him.

It was over by the time he reached Esosa. Twenty minutes since he’d heard the last gunshots, and by the time he stood in front of the smoking ruins of his home, even the dust raised by retreating murderers had settled back to earth.

Uzochi didn’t need the dust, though. He could track his enemies as he tracked game, with patience that assured him of a kill.

He would begin as soon as he had dug a grave for Enyinnaya and their unborn child. As soon as he had cooked a flank steak from the topi over glowing coals that once had been his home.

He needed strength for the pursuit.

Strength, and the ancient Lee-Enfield.

It meant his death to track the Itsekiri butchers, but he wouldn’t die alone.

CHAPTER ONE

Bight of Benin, Gulf of Guinea

They had flown out of Benin, from one of those airstrips where money talked and no one looked closely at the customers or cargo. In such places, it was better to forget the face and name of anyone you met—assuming any names were given—and rehearse the standard lines in case police came later, asking questions.

Which plane? What men? Why would white men come to me?

“One minute to the beach,” the pilot said. His voice was tinny through the earphones Mack Bolan wore.

The comment called for no response, and Bolan offered none. He focused on the blue-green water far below him and the coastline of Nigeria approaching rapidly. He saw the sprawling delta of the Niger River, which had lent its name both to the country and to Delta State.

His destination, more or less.

“Still time to cancel this,” Jack Grimaldi said from the pilot’s seat. He spoke with no conviction, knowing from experience that Bolan wouldn’t cancel anything, but giving him the option anyway.

“We’re good,” Bolan replied, still focused on the world beyond and several thousand feet below his windowpane.

From takeoff, at the airstrip west of Cotonou, they’d flown directly out to sea. The Bight—or Bay—of Benin was part of the larger Gulf of Guinea, itself a part of the Atlantic Ocean that created the “bulge” of northwestern Africa. Without surveyor’s tools, no one could say exactly where the Bight became the Gulf, and Bolan didn’t count himself among the very few who cared.

His focus lay inland, within Nigeria, the eastern next-door neighbor of Benin. His mission called for blood and thunder, striking fast and hard. There’d been no question of his flying into Lagos like an ordinary tourist, catching a puddle-jumper into Warri and securing a guide who’d lead him to the doorstep of an armed guerrilla camp, located forty miles or so northwest of the bustling oil city.

No question at all.

Aside from the inherent risk of getting burned or blown before he’d cleared Murtala Muhammed International Airport in Lagos, Bolan would have been traveling naked, without so much as a penknife at hand. Add weapons-shopping to his list of chores, and he’d likely find himself in a room without windows or exits, chatting with agents of Nigeria’s State Security Service.

No, thank you, very much.

Which brought him to the HALO drop.

It stood for High Altitude, Low Opening, the latter part a reference to Bolan’s parachute. HALO jumps, coupled with HAHO—high-opening—drops, were known in the trade as military free falls, each designed in its way to deliver paratroopers on target with minimal notice to enemies waiting below.

In HALO drops, the jumper normally bailed out above twenty thousand feet, beyond the range of surface-to-air missiles, and plummeted at terminal velocity—the speed where gravity’s pull canceled out drag’s resistance—then popped the chute somewhere below radar range. For purposes of stealth, metal gear was minimized, or masked with cloth in the case of weapons. Survival meant the jumper would breathe bottled oxygen until touchdown. In HAHO jumps, a GPS tracker would guide the jumper toward his target while he was airborne.

“Four minutes to step-off,” Grimaldi informed him.

With a quick “Roger that” through his stalk microphone, Bolan rose and moved toward the side door of the Beechcraft KingAir 350.

It was closed. Bolan donned his oxygen mask, then waited for Grimaldi to do likewise before he opened the door. They were cruising some eight thousand feet below the plane’s service ceiling of 35,000, posing a threat of hypoxia that reduced a human being’s span of useful consciousness to an average range of five to twelve minutes. Beyond that deadline lay dizziness, blurred vision and euphoria that wouldn’t fade until the body—or the aircraft—slammed headlong into Mother Earth.

When Grimaldi was masked and breathing easily, Bolan unlatched the aircraft’s door and slid it to his left, until it locked open. A sudden rush of wind threatened to suck him from the plane, but he hung on, biding his time.

He was dressed for the drop in an insulated polypropylene knit jumpsuit, which he’d shed and bury at the LZ. Beneath it, he wore jungle camouflage. Over the suit, competing with his parachute harness, Bolan wore combat suspenders and webbing laden with ammo pouches, canteens, cutting tools and a folding shovel. His primary weapon, a Steyr AUG assault rifle, was strapped muzzle-down to his left side, thereby avoiding the Beretta 93-R selective-fire pistol holstered on his right hip. To accommodate two parachutes—the main and reserve chutes, hedging his bets—Bolan’s light pack hung low, spanking him with every step.

“Two minutes,” Grimaldi said.

Bolan checked his wrist-mounted GPS unit, which resembled an oversize watch. It would direct him to his target, one way or another, but he had to do his part. That meant making the most of his free fall, steering his chute after he opened it, and finally avoiding any trouble on the ground until he’d found his mark.

Easy to say. Not always easy to accomplish.

At the thirty-second mark, Bolan removed his commo headpiece, leaving it to dangle by its curly cord somewhere behind him. He was ready in the open doorway, leaning forward for the push-off, when the clock ran down. He counted off the numbers in his head, hit zero in a rush and stepped into space.

Where he was literally blown away.

EIGHT SECONDS FELT like forever while tumbling head over heels in free fall. It took that long for Bolan to regain his bearings and stabilize his body—by which time he had plummeted 250 feet toward impact with the ground.