Полная версия:

Economics

Collins dictonary of

Economics

fourth edition

Christopher Pass, Bryan Lowes

& Leslie Davies

William Collins’ dream of knowledge for all began with the publication of his first book in 1819. A self-educated mill worker, he not only enriched millions of lives, but also founded a flourishing publishing house. Today, staying true to this spirit, Collins books are packed with inspiration, innovation, and practical expertise. They place you at the centre of a world of possibility and give you exactly what you need to explore it.

Collins. Do more.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Preface

Acknowledgements

Dictionary of Economics

a

b

c

d

e

f

g

h

i

j

k

l

m

n

o

p

q

r

s

t

u

v

w

x

y

z

Internet Resources

About the Authors

Copyright

About the Publisher

Preface

This dictionary contains material especially suitable for students reading ‘foundation’ economics courses at polytechnics and universities, and for students preparing for advanced school economics examinations. The dictionary will be useful also to ‘A’ and degree-level students reading economics as part of broader-based business studies, commerce or social science courses as well as to students pursuing professional qualifications in the accountancy and banking areas. Finally, it is expected that the dictionary will be of interest to general readers of the economic and financial press.

The dictionary provides a comprehensive coverage of mainstream economic terms, focusing in particular on theoretical concepts and principles and their practical applications. Key economic terms are given special prominence, including, where appropriate, diagrammatic illustrations. In addition, the dictionary includes various business and commercial terms that are relevant to an understanding of economic analysis and applications. It is, of course, difficult to draw a precise dividing line between economic and economics-related material and other subject matter. Accordingly, readers are recommended to consult other volumes in this series, in particular the Collins Dictionary of Business, should they fail to find a particular entry in this dictionary. In the interests of brevity, we have kept institutional minutiae and description, as well as historical preamble, to a minimum.

To cater for a wide-ranging readership with varying degrees of knowledge requirements, dictionary entries have been structured, where appropriate, so as to provide, firstly, a basic definition and explanation of a particular concept, then leading on through cross-references to related terms and more advanced refinements of the original concept.

Cross-references are denoted both in the text and at the end of entries by reproducing the keywords in small capital letters.

Acknowledgements

We should to thank Edwin Moore and Clare Crawford for their excellent work in preparing the manuscript for publication. Particular thanks are due to Sylvia Ashdown, Chris Barkby and Sylvia Bentley for their patience and efficiency in typing the manuscript.

Christopher Pass, Bryan Lowes

a

ability-to-pay principle of taxation the principle that TAXATION should be based on the financial standing of the individual. Thus, persons with high income are more readily placed to pay large amounts of tax than people on low incomes. In practice, the ability-to-pay approach has been adopted by most countries as the basis of their taxation systems (see PROGRESSIVE TAXATION). Unlike the BENEFITS-RECEIVED PRINCIPLE OF TAXATION, the ability-to-pay approach is compatible with most governments’ desire to redistribute income from high income earners to low income earners. See REDISTRIBUTION-OF-INCOME PRINCIPLE OF TAXATION, POVERTY.

above-normal profit or excess profit a PROFIT greater than that which is just sufficient to ensure that a firm will continue to supply its existing product or service (see NORMAL PROFIT). Short-run (i.e. temporary) above-normal profits resulting from an imbalance of market supply and demand promote an efficient allocation of resources if they encourage new firms to enter the market and increase market supply. By contrast, long-run (i.e. persistent) above-normal profits (MONOPOLY or super-normal profits) distort the RESOURCE ALLOCATION process because they reflect the overpricing of a product by monopoly suppliers protected by BARRIERS TO ENTRY. See PERFECT COMPETITION.

above-the-line promotion the promotion of goods and services through media ADVERTISING in the press and on television and radio, as distinct from below-the-line promotion such as direct mailing and in-store exhibitions and displays. See SALES PROMOTION AND MERCHANDISING.

absenteeism unsanctioned absences from work by employees. The level of absenteeism in a particular firm often reflects working conditions and morale amongst workers in that firm and affects the firm’s PRODUCTIVITY. See SUPPLY-SIDE ECONOMICS.

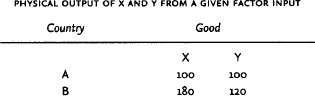

Fig. 1 Absolute advantage. The relationship between resource input and output.

absolute advantage an advantage possessed by a country engaged in INTERNATIONAL TRADE when, using a given resource input, it is able to produce more output than other countries possessing the same resource input. This is illustrated in Fig. 1 with respect to two countries (A and B) and two goods (X and Y). Country A’s resource input enables it to produce either 100X or 100Y; the same resource input in Country B enables it to produce either 180X or 120Y. It can be seen that Country B is absolutely more efficient than Country A since it can produce more of both goods. Superficially this suggests that there is no basis for trade between the two countries. It is COMPARATIVE ADVANTAGE, however, not absolute advantage, that determines whether international trade is beneficial or not, because even if Country B is more efficient at producing both goods it may pay Country B to specialize (see SPECIALIZATION) in producing good X at which it has the greater advantage.

absolute concentration measure see CONCENTRATION MEASURES.

ACAS see ADVISORY, CONCILIATION AND ARBITRATION SERVICE.

accelerator the relationship between the amount of net or INDUCED INVESTMENT (gross investment less REPLACEMENT INVESTMENT) and the rate of change of NATIONAL INCOME. A rapid rise in income and consumption spending will put pressure on existing capacity and encourage businesses to invest, not only to replace existing capital as it wears out but also to invest in new plant and equipment to meet the increase in demand.

By way of simple illustration, let us suppose a business meets the existing demand for its product, utilizing 10 machines, one of which is replaced each year. If demand increases by 20%, it must invest in two new machines to accommodate that demand in addition to the one replacement machine.

Investment is thus, in part, a function of changes in the level of income: I = f(ΔY). A rise in induced investment, in turn, serves to reinforce the MULTIPLIER effect in increasing national income.

Fig. 2 Accelerator. The graph shows how gross national product and the level of investment vary over time. See entry.

The combined effect of accelerator and multiplier forces working through an investment cycle has been offered as an explanation for changes in the level of economic activity associated with the BUSINESS CYCLE. Because the level of investment depends upon the rate of change of GNP, when GNP is rising rapidly then investment will be at a high level, as producers seek to add to their capacity (time t in Fig. 2). This high level of investment will add to AGGREGATE DEMAND and help to maintain a high level of GNP. However, as the rate of growth of GNP slows down from time t onward, businesses will no longer need to add as rapidly to capacity, and investment will decline towards replacement investment levels. This lower level of investment will reduce aggregate demand and contribute towards the eventual fall in GNP. Once GNP has persisted at a low level for some time, then machines will gradually wear out and businesses will need to replace some of these machines if they are to maintain sufficient production capacity to meet even the lower level of aggregate demand experienced. This increase in the level of investment at time t1 will increase aggregate demand and stimulate the growth of GNP.

Like FIXED INVESTMENT, investment in stock is also to some extent a function of the rate of change of income so that INVENTORY INVESTMENT is subject to similar accelerator effects.

acceptance the process of guaranteeing a loan, which takes the form of a BILL OF EXCHANGE that will be repaid even if the original borrower is unable to pay. This is done by a commercial institution which signs, that it ‘accepts’, the bill drawn up by the borrower in return for a fee. See ACCEPTING HOUSE.

accepting house a MERCHANT BANK or similar organization that underwrites (guarantees to honour) a commercial BILL OF EXCHANGE in return for a fee. See DISCOUNT, REDISCOUNTING, DISCOUNT MARKET.

account period a designated trading period for the buying and selling of FINANCIAL SECURITIES on the STOCK EXCHANGE. On the UK stock market all trading takes place within a series of end-on fortnightly account periods. All purchases and sales agreed during a particular account period must be paid for or settled shortly after the end of the account period.

accounts the financial statements of an individual or organization prepared from a system of recorded financial transactions. Public limited JOINT-STOCK COMPANIES are required to publish their year-end financial statements, which must comprise at least a PROFIT-AND-LOSS ACCOUNT and BALANCE SHEET, to enable SHAREHOLDERS to assess their company’s financial performance during the period under review.

acquisition see TAKEOVER.

activity-based costs see COST DRIVERS.

activity rate or participation rate the proportion of a country’s total POPULATION that makes up the country’s LABOUR FORCE. For example, the UK’s total population in 2004 was 59 million and its labour force numbered 29 million, giving an overall activity rate of 49%. Similar activity rate calculations can be done for subsets of the population such as men, women, ethnic groups, etc.

The activity rate is influenced by social customs and government policies affecting, for example, the school-leaving age and the proportion of young people remaining in further and higher education beyond that age; the ‘official’ retirement age and the proportion of older people retiring early or working beyond the retirement age. Opportunities for PART-TIME WORK and job-sharing can also influence, in particular female, participation rates. In addition, government TAXATION policies can also affect activity rates insofar as high marginal tax rates may serve to deter some people from offering themselves for employment (see POVERTY TRAP). See LABOUR MARKET, DISGUISED (CONCEALED) UNEMPLOYMENT.

actual gross national product (GNP) the level of real output currently being produced by an economy. Actual GNP may or may not be equal to a country’s POTENTIAL GROSS NATIONAL PRODUCT. The level of actual GNP is determined by the interaction of AGGREGATE DEMAND and potential GNP. If aggregate demand falls short of potential GNP at any point in time, then actual GNP will be equal to aggregate demand, leaving a DEFLATIONARY GAP (output gap) between actual and potential GNP. However, at high levels of aggregate demand (in excess of potential GNP), potential GNP sets a ceiling on actual output, and any excess of aggregate demand over potential GNP shows up as an INFLATIONARY GAP.

Over time, the rate of growth of actual GNP will depend upon the rate of growth of aggregate demand, on the one hand, and the growth of potential GNP, on the other.

actuary a statistician who calculates insurance risks and premiums. See RISK AND UNCERTAINTY, INSURANCE COMPANY.

adaptive expectations (of inflation) the idea that EXPECTATIONS of the future rate of INFLATION are based on the inflationary experience of the recent past. As a result, once under way, inflation feeds upon itself with, for example, trade unions demanding an increase in wages in the current pay round, which takes into account the expected future rate of inflation which, in turn, leads to further price rises. See EXPECTATIONS-ADJUSTED/AUGMENTED PHILLIPS CURVE, INFLATIONARY SPIRAL, RATIONAL EXPECTATIONS, HYPOTHESIS, ANTICIPATED INFLATION, TRANSMISSION MECHANISM.

‘adjustable peg’ exchange-rate system a form of FIXED EXCHANGE-RATE SYSTEM originally operated by the INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND, in which the EXCHANGE RATES between currencies are fixed (pegged) at particular values (for example, £1 = $3), but which can be changed to new fixed values should circumstances require it. For example, £1 = $2, the re-pegging of the pound at a lower value in terms of the dollar (DEVALUATION); or £1 = $4, the re-pegging of the pound at a higher value in terms of the dollar (REVALUATION).

adjustment mechanism a means of correcting balance of payments disequilibriums between countries. There are three main ways of removing payments deficits or surpluses:

(a) external price adjustments;

(b) internal price and income adjustments;

(c) trade and foreign-exchange restrictions. See BALANCE-OF-PAYMENTS EQUILIBRIUM for further elaboration.

While conventional balance of payments theory emphasizes the role of monetary adjustments (e.g. EXCHANGE RATE devaluations/depreciations) in the removal of payments imbalances, a crucial requirement in this process is for there to be a real adjustment in terms of industrial efficiency and competitiveness. An example will reinforce this point. Let us assume that, because UK goods are more expensive, the UK imports more manufactured goods from Japan than it exports manufactures to Japan. Since each country has its own separate domestic currency, this deficit manifests itself as a monetary phenomenon – the UK runs a balance of payments deficit with Japan, and vice-versa. Superficially, this situation can be remedied by, for example, an external price adjustment: currency devaluation/depreciation of the pound and currency revaluation/appreciation of the yen.

But price differences in the domestic prices of manufactured goods themselves reflect differences between countries in terms of their real economic strengths and weaknesses, that is, causality can be presumed to run from the real aggregates to the monetary aggregates and not the other way round: a country has a strong, appreciating currency because it has an efficient and innovative real economy; a weak currency reflects a weak economy. Simply devaluing the currency does not mean that there will be an improvement in real efficiency and competitiveness overnight. Focusing attention on the monetary aggregates tends to mask this fundamental truth. Thus, if the UK and Japan were to establish an economic union in which, as provided for by the European Union’s Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) arrangements, their individual domestic currencies would be replaced by a single currency, then, in conventional balance of payments terms, the UK’s deficit would disappear.

Or does it? It does so in monetary terms but not in real terms, that is, the disequilibrium manifests itself not in terms of cross-border (external) foreign currency flows but as an internal problem of regional imbalance. The ‘leopard has changed its spots’ – a balance of payments problem has become a regional problem, with the UK region of the customs union experiencing lower industrial activity rates, lower levels of real income and higher rates of unemployment compared with the French region. To redress this imbalance in real terms requires an improvement in the competitiveness of the UK region’s existing industries and the establishment of new industries by inward investment. For example, within the UK itself the decline of iron and steel production in Wales has been partly offset by the establishment of consumer appliance and electronics industries by American and Japanese multinational companies. See EURO, REGIONAL POLICY.

adjustment speed the rate at which MARKETS adjust to changing economic circumstances. Adjustment speeds will tend to vary between different types of market. For example, in the case of the FOREIGN EXCHANGE MARKET, the exchange rate of a currency will tend to adjust rapidly to EXCESS SUPPLY or EXCESS DEMAND for it. A similar rapid response tends to characterize COMMODITY MARKETS and MONEY MARKETS, with commodity prices and INTEREST RATES changing quickly as supply or demand conditions warrant. Product markets (see PRICE SYSTEM) tend to adjust more slowly because the prices of products are usually fixed administratively and are generally changed infrequently in response to major supply or demand changes. Finally, some commodity markets, in particular the LABOUR MARKET, tend to adjust more slowly still because wages tend to be fixed through longer-term collective bargaining arrangements. See WAGE STICKINESS.

administered price 1 a price for a PRODUCT that is set by an individual producer or group of producers. In PERFECT COMPETITION, characterized by many very small producers, the price charged is determined by the interaction of market demand and market supply, and the individual producer has no control over this price. By contrast, in an OLIGOPOLY and a MONOPOLY, large producers have considerable discretion over the prices they charge and can, for example, use some administrative formula like FULL-COST PRICING to determine the particular price charged. A number of producers may combine to administer the price of a product by operating a CARTEL or price-fixing agreement.

2 a price for a product, or CURRENCY, etc., that is set by the government or an international organization. For example, an individual government or INTERNATIONAL COMMODITY AGREEMENT may fix the prices of agricultural produce or commodities such as tin to support producers’ incomes; under an internationally managed FIXED EXCHANGE-RATE SYSTEM, member countries establish fixed values for the exchange rates of their currencies. See PRICE SUPPORT, PRICE CONTROLS.

administrator see INSOLVENCY ACT 1986.

ad valorem tax a TAX that is levied as a percentage of the price of a unit of output. See SPECIFIC TAX, VALUE-ADDED TAX.

advances see LOANS.

adverse selection the tendency for people to enter into CONTRACTS in which they can use their private information to their own advantage and to the disadvantage of the less informed party to the contract. For example, an insurance company may charge health insurance premiums based upon the average risk of people falling ill, but people with poorer than average health will be keener to take out health insurance while people with better than average health will tend not to take out such health insurance, so that the insurance company loses money because the high risk part of the population is over-represented among its clients.

Adverse selection results directly from ASYMMETRY OF INFORMATION available to the parties to a contract or TRANSACTION. Where there is hidden information that is private and unobservable to other parties to a transaction, the presence of hidden information or even the suspicion of hidden information may be sufficient to hinder parties from entering into transactions.

advertisement a written or visual presentation in the MEDIA of a BRAND of a good or service that is used both to ‘inform’ prospective buyers of the product’s attributes and to ‘persuade’ them to purchase it in preference to competing brands. Advertisements are usually featured as part of an ‘advertising campaign’ involving a series of presentations of the brand in the media over a run of weeks, months or even years that is designed to reinforce the ‘image’ of the brand, thereby expanding sales of the product and establishing BRAND LOYALTY. See ADVERTISING.

advertising a means of stimulating demand for a product and establishing strong BRAND LOYALTY. Advertising is one of the main forms of PRODUCT DIFFERENTIATION competition and is used both to inform prospective buyers of a brand’s particular attributes and to persuade them that the brand is superior to competitors’ offerings.

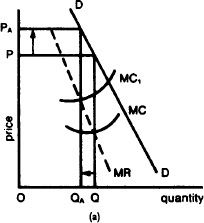

Fig. 3 Advertising. (a) The static market effects of advertising on demand (D). The profit maximizing (see PROFIT MAXIMIZATION) price-output combination (PQ) without advertising is shown by the intersection of the marginal revenue curve (MR) and the marginal cost curve (MC). By contrast, the addition of advertising costs serves to shift the marginal cost curve to MC1, so that the PQ combination (shown by the intersection of MR and MC1) now results in higher price (PA) and lower quantity supplied (QA).

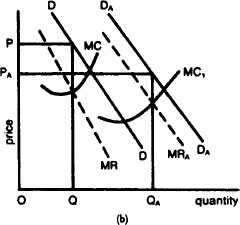

(b) The initial profit-maximizing price-output combination (PQ) without advertising is shown by the intersection of the marginal revenue curve (MR) and the marginal cost curve (MC). The effect of advertising is to expand total market demand from DD to DADA with a new marginal revenue curve (MRA). This expansion of market demand enables the industry to achieve economies of scale in production, which more than offsets the additional advertising cost. Hence, the marginal cost curve in the expended market (MC1) is lower than the original marginal cost curve. The new profit maximizing price-output combination (determined by the intersection at MRA and MC1 results in a lower price (PA) than before and a larger quantity supplied (QA). See BARRIERS TO ENTRY, MONOPOLISTIC COMPETITION, OLIGOPOLY, DISTRIBUTIVE EFFICIENCY.

There are two contrasting views of advertising’s effect on MARKET PERFORMANCE. Traditional ‘static’ market theory, on the one hand, emphasizes the misallocative effects of advertising. Here advertising is depicted as being solely concerned with brand-switching between competitors within a static overall market demand and serves to increase total supply costs and the price paid by the consumer. This is depicted in Fig. 3 (a). (See PROFIT MAXIMIZATION).