Полная версия:

Ghostland: In Search of a Haunted Country

It’s an artificial, man-made landscape, reclaimed in part from the sea. We learnt about it at school, about Cornelius Vermuyden and the Dutch-led drainage of the seventeenth century, and of the earlier history of this ague-ridden backwater: the watery world where in 1216 King John is said to have lost his royal treasure on an ill-fated crossing of one of the estuaries of the Wash, having a few days before in King’s Lynn contracted the dysentery that would shortly kill him; or of the Anglo-Saxon rebel Hereward the Wake who led Fenland resistance to the newly arrived Normans, but was more familiar through having lent his name to the Peterborough-based radio station my classmates and I would listen to – in particular hoping they’d read out the name of our school on a snowbound day and that it wouldn’t be opening, a rare mythic event that actually came to pass on two occasions. Mostly though, the story of the area’s past is vague in my mind, like the inconstant lie of the land in the days prior to pumping stations. Even my own connections with the region seem increasingly tenuous, liable to be leached away by one of the local rivers: the Great Ouse, the Nene, the Welland. Or the River Glen, which my grandfather – a real-life incarnation of a character from Graham Swift’s Waterland – lived alongside.

Waterland was published in 1983 and was shortlisted for the Booker Prize in the same year. It is a novel about the forces inherent in human nature that tear people and families apart, how past events haunt the present. But, above all, for me it’s a book about the unnerving flat landscape of my youth. Though I must qualify this, because it would be wrong to regard the Fens as forming a solid, distinctive whole; the country of my childhood had its own boundaries based upon the places we’d visit regularly as a family, stretching a varying number of miles in each direction from our house, but outside of which the more removed outposts of flatness seemed alien and otherworldly. One such locality that we occasionally passed through was the tiny cluster of residences that formed the village of Twenty. In 1982 it acquired a new black-lettered sign that sat below its official name – ‘Twinned with the Moon’ it read; soon afterwards some local joker spray-painted the retort ‘No Atmosphere’ beneath.

In my reading of the novel, Waterland has its setting among the ‘Black Fens’ beyond Wisbech, a town which is itself reworked by Swift into Gildsey, with the real Elgood’s brewery standing in for the book’s fictional Atkinson’s. Despite being only a forty-minute drive from my home, Wisbech was an unacquainted place, less familiar to me than the geographically more distant London, which most years we would make a pilgrimage to on the train. Wisbech was merely somewhere we skirted on visits to Welney, where my mother took us to watch the winter gatherings of wild swans that sought refuge on the dark fields – terrain only slightly more hospitable than their native Iceland and Siberia.

Thomas Bewick, the eighteenth-century illustrator and author of the landmark History of British Birds, whose surname is commemorated by those squat-necked Arctic swans we would watch feeding on potatoes on the floodlit washes, also features tangentially in M. R. James’s story ‘Casting the Runes’. A victim of the story’s black-magic curse is sent in the post one of Bewick’s woodcuts that ‘shows a moonlit road and a man walking along it, followed by an awful demon creature’. If he has not concocted his own work by Bewick, James is most likely referring to the same tailpiece vignette that so disturbs the young Jane Eyre in Charlotte Brontë’s novel – a tiny extraneous illustration tucked into the blank space at the end of the 1804 ornithological tome’s chapter on the black-throated diver.* According to Brontë’s heroine, Bewick’s terrifying etching depicts a ‘fiend pinning down the thief’s pack’. And though there’s nothing that necessarily identifies the man as a law-breaker, the act of carting a heavy bag down a dark country lane does seem suspicious; the attached medieval-looking winged devil that’s doing its best to pry open the contents of the sack does little to assuage our suspicions that the bearer has been up to no good and is getting his hellish comeuppance.

The narrator of Waterland, Tom Crick, is a history teacher who is being encouraged to take early retirement due to budgetary restraints at his school. ‘We’re cutting back on history,’ his headmaster drily informs him, though ultimately it’s the mental breakdown of his wife that speeds the process along. A precocious boy in his class questions the point of learning about what has gone before: ‘What matters,’ Price declares, ‘is the here and now. Not the past.’ So, in order to demonstrate how history does still result in consequences for the here and now, Tom Crick begins to tell them of his own eddying past, the history of the watery landscape of the ‘fairy-tale place’ of his youth.

Waterland swirls between earlier days and the present, between the personal family dramas of the Crick and Atkinson families, and of the shifting silts of greater events such as the Napoleonic or First World Wars, whose eventual settling has a future effect on the imprecise borderlands of the far-off Fens. And, in a nod to Melville’s Moby-Dick, there is even an eight-page digression into the slippery natural history of the European eel, a species my grandfather, a keen angler, was well acquainted with.

I read the novel aged sixteen, a year or two after my brother had first turned its pages. It’s testament to the book’s power that my father, who usually distracted himself with the crime novels of Ed McBain or the thrillers of Frederick Forsyth (who he recalled meeting when they both worked in King’s Lynn at the end of the 1950s), and my grandfather – more comfortable with the westerns of Louis L’Amour – both seemed to take to it. For me, I think (and probably for them too), Waterland’s initial magic came from its setting; although its events largely occurred in a time well before I was born and in a skewed version of a place some twenty miles distant, it was still a landscape I felt I knew – and a landscape I’d never seen depicted in fiction before.

The key attraction, however, was that the Cricks were lock-keepers. Because Grandad had been one too, looking after the antiquated sluices at the confluence of the Welland and the Glen, and at the terminus of the Vernatt’s Drain. In common with the Cricks of the novel, Nan and Grandad lived in a riverside cottage that came with the job. It too was a fairy-tale dwelling of sorts, located in a place whose own name was something of a misnomer: Surfleet Reservoir (though Seas End on maps), the latter word referring to the ultimately failed eighteenth-century plan to divert river water into an artificial lake to aid the drainage of local farmland. My grandparents’ post-war brick bungalow, a veritable palace among the nearby wooden holiday chalets and ramshackle fishermen’s huts that lined the Glen, was where my mother spent her teenage years before she left to marry my father beneath the leaning steeple of the main village’s church, moving six miles upriver to the house where I grew up. ‘The Res’ (as locals still refer to it) was an odd enclave populated by weekenders who moored their boats on the seaward side of the sluice – a deep tidal channel fringed by tall reeds – from where they would head out for a spot of sea fishing, or others who preferred to spend the summer sitting outside their chalets chatting to their neighbours while their children played in the river. By all accounts the place had a distinct sense of community back then, and even today has a different feel to the rest of the uniform, arable-dominated area – bringing to mind some timeless Dutch canal-side idyll.

My grandparents departed this watery haven on Grandad’s retirement, moving to a ground-floor 1970s council flat in nearby Spalding fitted with wide doorways, a high-seated toilet, and red pull-cords that would summon the local old people’s warden in an emergency. The freedom of the lock-side home I cannot remember the inside of (I would have been two when they left it) was exchanged for more practical – but more humdrum – disabled-friendly accommodation that could better cope with Nan’s ongoing, crippling physical deterioration from rheumatoid arthritis.† As her condition worsened she developed a complete reliance on my grandfather who, in a strange role reversal for a man born in 1909, became her chief carer and cook, lugging her into her wheelchair to transport her to the bathroom and bedroom. Occasionally, the pair of them would argue with a causticity that now, I think, was borne out of Grandad’s frustrated inability to improve the situation. But, at other times, there was a tenderness in the way he gently pipetted artificial tears into her desert-dry eyes.

I follow the familiar route that hugs the river and leads away from my home town – I can still recall every curve even after all this time. This was the way I would ask my parents to come if we were returning from Peterborough of an evening, in the hope I’d spot an owl sitting on one of the fence posts strung along the bottom of Deeping High Bank. Sometimes Mum would pick me up from school and drive Grandad and me at dusk over the undulating road, while we watched through the windows for the silent-winged birds. In my formative years I claimed a kind of ownership of the place, mistakenly believing it was named ‘Deeping Our Bank’ – for the hours we spent here, it might as well have been.

On the face of it there’s not much to get excited about: the first stretch skirts a grass-covered strip to the left and wide fields of crops to the right, while a barbed-wire fence borders the roadside ditch. Today it’s empty, but over the years various birds of interest alighted here before us: a pair of stonechats, neat little passerines, usually took up winter residence; once, a russet-barred sparrowhawk gripped a bloodied linnet in his talons; and in spring, Pinocchio-billed snipe crouched on the wooden posts in full view, their cryptic brown plumage offering no camouflage against the green of the backdrop. But the highlight was the ghost-lit barn owls that fluttered ethereally in our headlights, or materialised, seemingly from nowhere, in the late afternoon sunshine.

Always you wanted owls.

Past where the road jinks to the left and twists up the bank, bringing the river into view, is a pale-bricked barn that looked out of place, like some Spanish mission picked up and transposed to the middle of this flatness. Just beyond, tucked behind the bank, is a pond. We rarely saw anything on it – except once, when Mum braved treacherous snow on one of the fabled occasions when school was closed to drive the two of us along the track. The river was frozen solid, but not the pit: a redhead female smew, a small, toothed diving duck from the continent, had found the last ice-free stretch in the vicinity.

That day sits in my memory like one of my favourite childhood books, Susan Cooper’s The Dark is Rising – the second (and arguably best) in the five-title series of the same name. The 1973 children’s novel followed eight years after the Cornwall-set Over Sea, Under Stone and, in truth, feels very different and aimed at an older audience (Cooper had not originally planned on it being part of a series). It dispenses with the child leads from the opening book (though they feature again later), retaining only the wizard Merriman – King Arthur’s Merlin. What we do get in The Dark is Rising, however, is the arrival of eleven-year-old Will Stanton, soon to discover that he’s the last of the Old Ones, on the side of the Light and tasked with keeping the forces of Dark at bay in a Manichaean struggle. It is a book I loved when I first read it (I would have been a similar age to its central character), especially its depiction of the longed-for snowy Christmas that renders its time-shifting Thames Valley setting into a magical, albeit malevolent, wilderness. It’s a remarkable evocation of the wintry English countryside (reminiscent of the snow in The Children of Green Knowe), particularly when you learn that Cooper left England for Massachusetts in 1963 with her American husband, writing all but the first of the sequence in either New England or the couple’s house in the British Virgin Islands:

The strange white world lay stroked by silence. No birds sang. The garden was no longer there, in this forested land. Nor were the outbuildings nor the old crumbling walls. There lay only a narrow clearing round the house now, hummocked with unbroken snowdrifts, before the trees began, with a narrow path leading away.

The scene reminds me of an earlier remembrance – the first time I saw proper deep snow, which had fallen on our garden overnight, anaesthetising the land and deadening all sound. Dad and I placed sticks in the snow-hills that the wind had sculpted, marking each one with a makeshift wooden trig point that reminded me of the mountains I longed to climb on the holidays we took, far removed from those flatlands.

The river is choppy, its banks a dirty green – there’s not a hint of snow in the sky – but I’m surprised by the new areas of wildlife habitat that have been cut alongside the water since the last time I was here: miniature inlets and scrapes, and a fledgling reedbed that would have been perfect back then for me to scan. In this same spot we watched transfixed on a correspondingly biting afternoon as a bare-chested man bobbed beside the river’s metal-reinforced far bank, a few strokes behind a paddling cow that he was trying to coax back onto dry land. My father knew him, he was a local farmer.

At the aptly named Crowland, a parliament of rooks is feeding amid a ploughed beet crop. I slow as I pass the town’s Civil War-ruined abbey, commemorated in a gothic sonnet by the ‘peasant poet’ John Clare, whose village of Helpston is only nine miles away, and whose wife spent her dying days in my home town:

We gaze on wrecks of ornamented stones,

On tombs whose sculptures half erased appear,

On rank weeds, battening over human bones,

Till even one’s very shadow seems to fear.

I stop in the heart of the nothingness, pulling onto the head of a dirt drove that branches off at a right angle to the main route’s undulating, cracked tarmac. It’s a bleak place, the very same stretch of road where, as teenagers, my friends and I would switch off our headlights while motoring at speed, briefly plunging ourselves into blindness. We were young and rash, fortunate not to suffer the classic Fenlander’s end and find ourselves drowning in two foolish feet of lonely water at the bottom of one of the ubiquitous steep-sided dykes that line those routes. A patch of ice at the wrong moment could have created a local tragedy and transformed us into a carload of ghouls.

If we had perished that way, perhaps one of us might have been fated to a curious, brief half-life like the main character Mary Henry, a church organist, in Carnival of Souls. At the start of the dreamlike, low-budget black-and-white 1962 movie she washes up on a sand bar more than three hours after the car she was a passenger in has plunged into the Kansas River, killing her two companions. She moves from the scene of the tragedy to Utah, where she finds herself stalked by a mysterious figure – ‘the Man’, played by the film’s director Herk Harvey – and a cast of undead dancers at the abandoned Saltair bathing pavilion that looms out of the Great Salt Lake’s fluctuating dried-out flatness, a landscape not unlike the Fens. The film’s eerie discordant organ music has a similarly hypnotic effect on Mary as the hurdy-gurdy of Lost Hearts does on Stephen. And, indeed, as both soundtracks seem to have on me.

‘It was though – as though for a time I didn’t exist. No place in the world,’ Mary says, after a fugue-like episode where she cannot hear external sounds or interact with her fellow townsfolk, before the song of a bird brings her back into the now. The young drowned organist, cast in the role of an awkward outsider, has been allowed to live out a brief window of her lost youth: events not actualised that should never have come to pass. Her limbo is a fleeting foretaste of what could have been.

Like my family’s own future among these formless fields.

Fear and paranoia were staples of growing up during the late 1970s and early 1980s. Made in 1973, the year I was born, Lonely Water is a public information film I vividly remember seeing at the cinema as a boy, before whatever main feature I’d been brought to see.‡ In recent years it has acquired a deserved cult reputation for its dark, warning content. Watching it now you’d think there was little danger that any child who saw Lonely Water would set foot on a riverbank or the shoreline of a reservoir ever again. Yet I did still go fishing with only a friend for company, and we often did end up messing about near the water, which makes we wonder whether the film’s message was lost on their target audience. Perhaps the known risk added an illicit thrill we found impossible to resist?

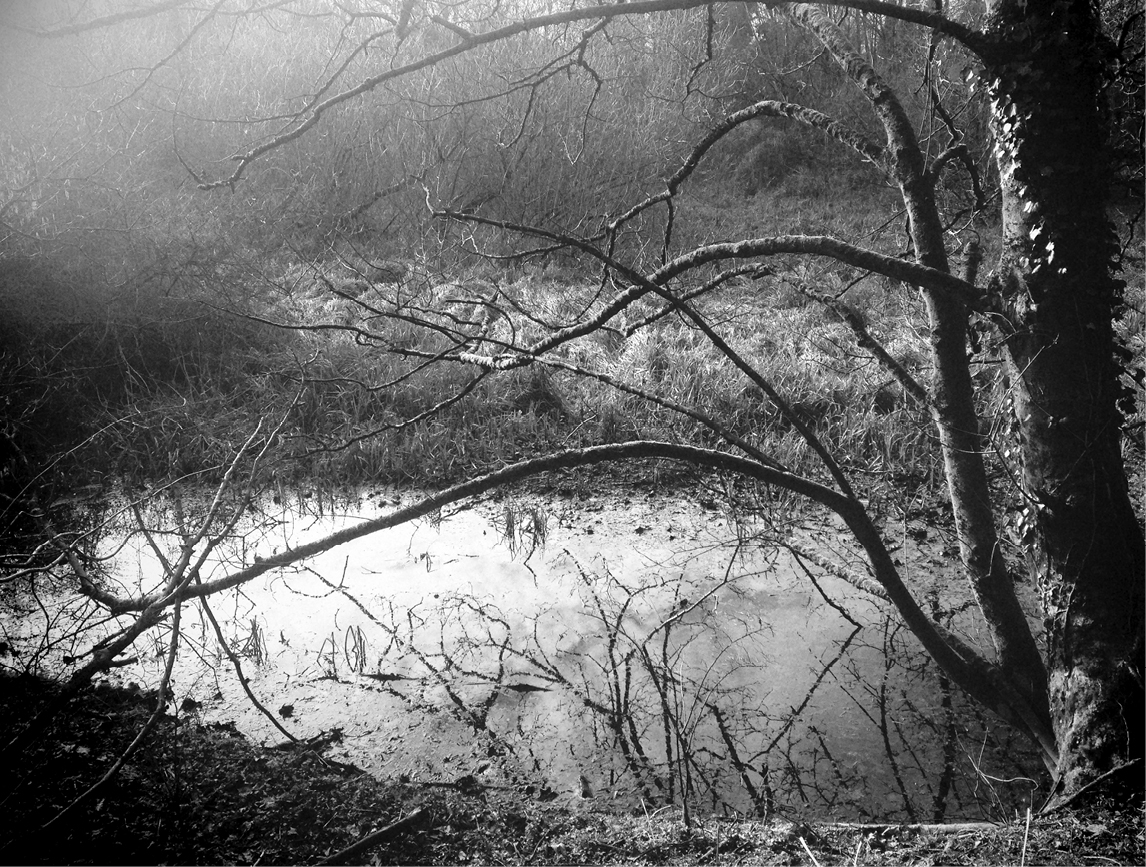

Just a minute and a half long, the film opens with a panning shot across a black, twig-strewn pond, accompanied by Donald Pleasance’s chilling voiceover – ‘I am The Spirit of Dark and Lonely Water, ready to trap the show-off, the unwary, the fool’ – before the camera lingers on a hooded Grim Reaper standing in the shallows. We cut to another hooded figure, a blue-coated boy, who is playing with his friends on the muddy bank of a gravel pit. One of his companions, a lank-haired urchin, is poking a stick at a football that’s fallen into the water. We look up at them from the position of the ball, towards the down-jabbing twig and the four shouting children; the Spirit looms behind them, unbeknown, as the boy slips on the bank. Without learning the fate of the show-off (though the implication is obvious), we switch to a bucolic scene – a tranquil duck-filled millpond. This time a lone older lad is leaning forwards, supporting his weight on the bough of an overhanging tree, again to stab at some untouchable object. Donald Pleasance’s narrator informs us with great delight: ‘This branch is weak. Rotten. It’ll never take his weight.’ We hear the snap as it falls, the cloaked voyeur observing the unfolding tragedy through the nearby reeds.

The final scene jumps to a close-up of a ‘Danger No Swimming’ sign, spelled out in large red letters. ‘Only a fool would ignore this … But there’s one born every minute.’ A pile of clothes and a pair of shoes have been left among a mountain of detritus as the camera pans to the pit where a boy is struggling and shouting for help. ‘Under the water there are traps: old cars, bedsteads, weeds, hidden depths. It’s the perfect place. For an accident.’

Watching Lonely Water again, the grisly relish Donald Pleasance’s Spirit takes in his description of these lurking dangers is one of the most unnerving elements about it – this brief voiceover role might well be the most frightening of his long career. The lad, fortuitously, is rescued from the water by two sensible passing children who chide him in thick cockney accents – ‘Oi mate, that’s a stupid place to swim’ – and the Spirit is exorcised, leaving just a discarded robe on the muddy ground that is thrown into the water by his rescuers. But Pleasance is determined to have the last word, the Spirit’s voice reverberating as the camera lingers on the cape that is by now sinking beneath the brown waves:

‘I’ll be back. Back. Back …’

In works of unsettling fiction, Britain’s inland waterways are not commonly a haunted geographical feature, though we have a vengeful spirit born of water in M. R. James’s Dartmoor-set ‘Martin Close’, and a canal trip looms large in Elizabeth Jane Howard’s ‘Three Miles Up’. There is also a story that I cannot seem to shake by an unfairly neglected author of the second half of the twentieth century: A. L. Barker’s ‘Submerged’.

Audrey Lilian Barker was born in Beckenham, Kent, in 1918, and died in a nursing home in Surrey in 2002. She wrote eleven novels and numerous collections of stories (which include several supernatural tales); her novel John Brown’s Body was shortlisted for the Booker Prize in 1970, and her debut collection of short works, Innocents, won the inaugural Somerset Maugham Award in 1947. ‘Submerged’ is part of that collection and a powerful piece. It opens with a vivid description of a rural English river and its pastoral surrounds – of the purple loosestrife, yellow ragwort and red campion that cover its banks. Yet in this mild, sun-dappled scene we are soon reminded of the menace that lurks beneath the water’s gentle eddies.

He wasn’t supposed to swim in the river anyway, there was some talk about its being dangerous because of the submerged roots of trees. Peter knew all about those, they added the essential risk which made the river perfect.

In the striking mid-century artwork of the first edition’s cover, the story’s adolescent protagonist is depicted as a stylised green figure part-way through a plunging dive. As the boy Peter engages in his lone swims he delights in exploring the tangled willow roots and branches that form his new benthic world; as readers we delight too, initially at least, as Barker paints an intoxicating picture of wild swimming that would make Roger Deakin proud. Having discovered a sort of tree-formed underwater tunnel, Peter has the realisation that he must explore its hidden folds, an epiphany made concrete by the sudden ethereal apparition beside him of a fleeting kingfisher, ‘a flicker of cobalt, bronze and scarlet’.

I too remember my first proper view of a kingfisher, a squat-tailed sprite on the railing beneath the dilapidated railway bridge at the back of my aunt’s house. It was Christmas Day 1987 and Dad and I had gone for a walk to try out my new big joint birthday and Christmas present – a telescope, so that now on trips with my brother I would have my own optics to look through at all those distant waders and wildfowl. The kingfisher perched below us for two, perhaps three, seconds before propelling itself like a tightly wound clockwork toy down the right-hand bank of the Vernatt’s Drain, the uniformly straight channel that ran all the way to my grandparents’ former home.§ Finally the bird came into focus, on a wooden jetty that protruded through the reeds, the middle of its back illuminated electric-blue through my scope despite the dullness of the day. I was elated. Even my father, who though mildly interested in wildlife was no wide-eyed naturalist, knew we’d been honoured with a glimpse of the fantastic.

After Peter witnesses his kingfisher in the story, he dives back down to his tunnel, conquering its dark secrets, before coming to rest on the water’s sunlit surface in an afternoon reverie. This heady state is ruined by the appearance of a stranger: ‘It was a woman in a red mackintosh. No longer very young, and so plump that the mackintosh sleeves stretched over her arms like the skin of scarlet saveloys.’ The woman orders the half-concealed boy out of the water, in anticipation of the imminent arrival of her presumed partner, an oafish brute who, she tells Peter, wants to murder her. ‘He won’t lay a finger on me if there’s a witness and a chance he’d swing for it …’ Peter emerges reluctantly, remaining close to the thick cover of the bank’s vegetation. The man arrives and the pair argue, but the expected violence does not come. The boy’s sacred bathing place has, none the less, been sullied by their presence, its rhythms punctured by the intrusion of this odd, aggressive couple, with their air of illicit adult sexuality.