Полная версия

Полная версияLife and Lillian Gish

Three or four years ago, in a big barn of a theatre in Southern France, the writer of these pages first saw “The Scarlet Letter” and went home in a daze, waking up now and then to damn his Puritan ancestors. In the seat next his, had sat a small, intense Frenchwoman, who, at one point, had said, tearfully, to her companion: “Regardez, Léontine, regardez son pauvre petit dos!” (Look, Leontine, look at her poor little back!) And just now I read a paragraph which said: “Lillian Gish can convey more pathos with her back than any other actress with all her features.”

I agree with that, and I am not going by my first impression. I have seen the picture again—very recently, with Lillian, in the New York Metro-Goldwyn projection room. Association had destroyed none of the illusion. The effect was the same—heightened.

We left the crash and glare of Ninth Avenue for the comparative seclusion of a cab. Lillian said, presently:

“I was too immature to play that part. She was a woman. I looked just like a child.”

“You looked young, certainly, but not too young for Hester—that Hester. Of course, the real Hester—supposing there ever was one—was not at all your Hester. She was less—more—what the others were.”

She assented, a little doubtfully. I stumbled on:

“If I might offer a humble opinion, you did not turn Lillian Gish into Hester Prynne; you turned Hester Prynne into something—well—something more exquisite.”

“Some of the critics didn’t think so; they said–”

“I know the things they said. I have those scrapbooks, where you carefully preserved all the worst ones. A critic—a young critic—does not think he is doing his duty unless he puts a little sting into what he writes. The cup he offers must have its drop of hemlock, even when he proffers it on bended knee.”

“La Bohême” and “The Scarlet Letter” were popular abroad. From Europe, from the farthest East, the letters came. Oriental young men, in exquisite calligraphy and quaint phrase, told her how she was adored, begged for a photograph, a written line. Some suggested pictures they hoped she would do—“Joan of Arc” among them.

VII

“THE FIRST LADY OF THE SCREEN”

During Lillian’s absence in England, a scenario for a new picture bad been prepared for her, based on the song of “Annie Laurie,” believed to have a wide human appeal. All the sets were ready, the costumes had only to be fitted. The day of her arrival, Lillian went to the studio, and next day began on the scenes. Lillian and Miss Moir agree that it was a fearfully hot summer, and that the velvet costumes for Annie weighed fifteen pounds each. Lillian did not care much for the story, and cared for it a good deal less when she learned that Bonnie Annie Laurie, for whom someone had been ready to lie down and die, had, in her later years, turned into an old gossip. Of course, in the picture, her lover is a member of another clan, and there is the usual treachery, with a great deal of confused fighting, and struggling through artificial snow which, in that deadly heat, just about blistered your fingers when you touched it. But Lillian was faithful, and did her sweltering best.

One Sunday, Miss Moir, thinking how much it would be appreciated by the company, “on location,” drove out there with several gallons of ice-cream. Unfortunately, that day, rehearsal broke up early. She met Lillian on the road, but two girls couldn’t eat all those gallons of cream, and for some reason the rest of the company failed to materialize. They tried to give the surplus away, to passersby, but when several had haughtily refused, they dropped the rest into a ditch.

“Annie Laurie,” first given at the Embassy Theatre, New York, May 10, 1927, appears to have been well received. As usual, the notices spoke of Lillian as “lovely,” and “winning,” and “charming,” but they lacked the enthusiasm of those written of Hester and Mimi, and they were doubtful of the picture itself.

The reason is clear enough: the tame, or partially tame, Scot of today, has commendable points; he knows about engines, and Greek, and often plays a fair game of gowf. But the range species of some centuries ago, was a good deal different—an unprepossessing, evil-smelling, hairy type, who had clans and feuds and delighted in running off his enemy’s cattle, or cannily luring him into a cave and smoking him to death, or, as in this instance, into a castle, to murder him in cold blood. That earlier Scot was hardly the thing to offer to a delicately-nurtured picture audience. Even Norman Kerry as Ian MacDonald, even Lillian as Annie Laurie, could not make him palatable.

Lillian, however, was riding on the top wave. An English company offered her the lead in “The Constant Nymph”; a great German company offered the part of Juliet: “Cannot tell you how delighted we should be, if the remotest possibility”; de la Falaise offered her the part of Joan of Arc, in a picture for which Pierre Champion, the great French authority on Joan, had prepared the scenario. To the last named, she replied that she had long been considering the part of Joan, and put the matter aside with real regret.

And many wanted to write of her. Whatever she did, or was about to do, was news. A magazine, Liberty, sent a gifted young man, Sidney Sutherland, all the way to the Coast to see her. He had expected to do one, possibly two, articles, but his editors asked for more, and under the general title of “Lillian the Incomparable” continued his chapters—“reels” as he not inaptly termed them—through nine weekly installments!

On any excuse, and with no excuse at all, other than what it presented, and stood for, periodicals carried her picture. Vanity Fair published a full front-page portrait, by Steichen, nominating her “The First Lady of the Screen.”

Miss Moir says that she was always being approached by lovesick young men, anxious to find out all they possibly could about the object of their affections.

They wanted to know what she ate, what she read, what she did after studio hours, what she talked about. I did the best I tactfully could to gratify their curiosity, but I well remember the look of pained surprise which came over the face of one admirer when I told him that Lillian took a cold plunge every morning, exercised vigorously and did a really spirited Charleston. I suppose this was all contrary to his idea of what such a fragile, ethereal being should do.

Flowers were always arriving, enough to start a florist’s shop. And permanent gifts—anonymous ones, some of them, and of great value: a large, magnificent fire opal set with diamonds; an exquisite point lace shawl, so perfectly suited to her personality that the donor must have had taste as well as an opulent purse.

Photographers were always besieging her to pose for them, and painters. The latter rarely caught her personality. It was such an elusive thing. The quick camera was better at it. Frequently, too, she was caricatured, and it is only fair to say that most of the caricatures were among the best of the results—strikingly like her: “more like me than I was like myself,” she said.

She shared her success with those less fortunate—gave freely, money, advice to young aspirants, help to sister-players and would-be players—provided jobs for them. One day a girl with a face a good deal like her own, and the fairy name of Una Merkel, came to see her. Screen fans know Una Merkel very well today, but perhaps not many know that she is a poet. One Christmas, in appreciation of what Lillian had done for her, she wrote and had beautifully printed on a card of greeting, some verses, two of which follow:

To Lillian GishIf I could breathe on canvas white my dreams,I’d dip my fancy into tubes which heldLife’s colors—pure, of sheerest loveliness,Then—I’d paint—you.I’d borrow of the Lily its perfume,Of day—the misty beauty of its dawn;Then of the world I’d take a tear—a smile,And I’d have—you.VIII

“WIND”

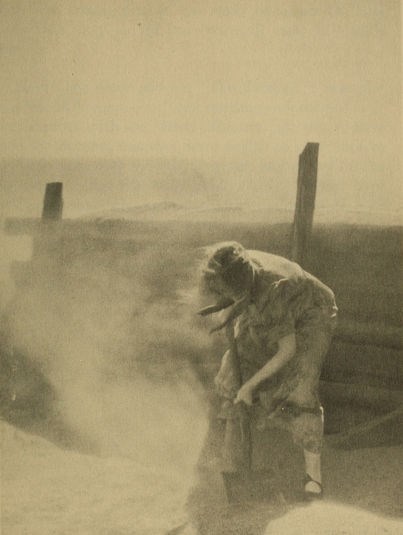

There had appeared an anonymous novel (later acknowledged by Dorothy Scarborough), a tale of sickening horror, entitled “Wind.” It was the story of a young, refined Southern girl, who goes to Texas in an earlier day; is made desperate by the wind and blowing sand and hard human circumstance; marries a rough cowboy; is violated by a man she had met on the train; murders him and goes mad—a category of black disaster.

It was regarded as fine material for a picture, well-suited to motion photography, because of the wild, tireless wind—perfect symbol of motion, and of the fierce action of the story. A director, Clarence Brown, was highly enthusiastic over the possibilities of “Wind” on the screen, but a favorable decision might have been less quickly reached had all the conditions been foreseen. For making the picture was an experience nearly as desolating as the story. When the studio scenes were finished, a trek of wagons, trucks and motor busses, loaded with paraphernalia, an entire company of actors, a big crew of technical assistants, mechanics, etc., the whole accompanied by eighty mounted cowboys, invaded the blistering Mojave Desert, in the cause of art.

Mr. Brown, after all, was not to direct. He had been sent off to Alaska, on the “Trail of ’98,” and could not, it seemed, finish it. Victor Seastrom was given the direction of “Wind,” and again Lars Hansen was Lillian’s leading man. Satisfactory as far as it went. They had waited a long time on Brown—until they could wait no longer. Spring had come. The Mojave in midsummer was unthinkable. So that big procession one morning got in motion.

It was May, and it was hot. Arriving at Mojave, the men took up quarters in a train that had been shunted onto a disused siding—Lillian, Miss Moir and a few others in a flimsy little hotel, opposite the tracks, where engines switched and banged most of the night long. It was a Harvey hotel, which was the best that could be said for it; the food at least would be good. Cool enough at first, the weather presently became unbearably hot. Whereupon a new difficulty presented itself: Film coating melted from the celluloid. No developing could be done with the thermometer at 120 in the shade. They tried freezing the films, but this made them brittle, like thin glass. Finally, they packed them, frozen, and rushed them by special cars to the Metro laboratories, one hundred and forty miles away, to be carefully thawed out.

And the human misery of it! Miss Moir writes:

Quivering veils of heat lay over the desert, there was no shade anywhere, and a burning wind blew all day long, raising blisters on your face, taking every bit of skin off your lips. I shall never forget the appearance of the crew during that picture. To protect their faces from the sun they all wore a heavy blackish make-up while their cracked and swollen lips were covered with some sort of white stuff. Add to this goggles, and handkerchiefs tied round their necks, and you can imagine that most desperate looking gang to be seen anywhere on that desert. When the studio executives saw the first rushes they were so horrified at Lars Hansen’s unromantic appearance that they ordered the whole sequence to be done again and Lars Hansen to appear shaven and clean, as they argued that no girl could possibly entertain romantic thoughts for such a hairy ruffian.

The cowboys added interest and excitement to the adventure. Long, lean blasphemous individuals, reckless of everything, gambling the minute they were not needed for a scene.

To which Lillian adds:

“It was the very worst experience I ever went through. Temperature 120 in the shade. In the sun…? One man burned his hand quite badly opening the door of a motor. We had eight wind machines, and in the studio, to match up with the blowing sand outside (supposed to be blowing in the doors and windows), we used sulphur pots, the smoke giving the effect of sand blowing in. The sand itself was bad enough, but the pots were worse. I was burned all the time, and was in danger of having my eyes put out. The hardships of making ‘Way Down East’ were nothing to it. My hair was burned and nearly ruined by the sulphur smoke. I could not get it clean for months. Such an experience is not justified by any picture.”

Nature seems to have wearied of their evil-smelling feeble devices, and one day gave an example of what she could do herself. Miss Moir, graphically:

A few days before we finished the scenes up there it turned cold. Towards the end of the afternoon work was stopped by a terrific sandstorm. A howling wind, which soon assumed the proportions of a hurricane, tore down from the mountains sending the sand whirling in dense masses before it. The sky was black and everything was obscured by a veil through which we could dimly perceive the figures of the cowboys bent forward on their saddles, horse and rider braced against the oncoming fury, making for camp. There was an extraordinary beauty about the scene, as Lillian and I stood for a moment and watched it before getting into the car, and I could appreciate the feeling in her voice when she said “Oh, how I wish Mr. Griffith was here. How he would have loved to photograph that.”

All night long the storm raged while our shaky little hotel quivered to its foundations. As we lay in bed trying vainly to sleep, we could see the flimsy walls of the hotel bending before the onslaught, and in the morning the room was full of sand which had leaked in through every crevice of the ill-built structure.

This was exactly what they had come up there to produce, but apparently they made no use of it. One remembers Griffith waiting for the blizzard in New England, and echoes Lillian’s heartfelt utterance. The day had come when Nature’s effects were no longer in favor—were even resented, as an imitation; and one who has seen the picture must confess that those eight wind machines were not easily to be outdone.

The most depressing of Lillian’s films, “Wind,” is one of the best—beautiful in its sheer ferocity. Nemirovitch Dantchenko, distinguished manager, playwright and producer, of the Moscow Art Theatre, being then in Hollywood, after a preview of it, wrote as follows:

I want once more to tell you of my admiration of your genius. In that picture, the power and expressiveness of your portrayal begat real tragedy. A combination of the greatest sincerity, brilliance and unvarying charm, places you in the small circle of the first tragediennes of the world.... One feels your great experience and the ripeness of your genius.... It is quite possible that I shall write [of it] again to Russia, where you are the object of great interest and admiration by the people.

“WIND” Letty, burying the man she had killed

For some reason, “Wind” was not released until late in the year. When it finally appeared, the time for it was brief—the talking picture was ready to invade the land—but that story—a sad one—we shall come to a little later.

Lillian’s last silent picture, “The Enemy,” a war picture, laid in Vienna—not very startling—closed her two-year contract with the Metro company. She was to have made six pictures, but they were unable to give them to her. Both sides were satisfied, however, and parted on the pleasantest terms. Only too gladly, Lillian would have made another picture, had conditions been otherwise. The company on its part had no word of complaint, even paid her for one day extra time, something over a thousand dollars, a complete surprise, for she had taken no account of that day.

IX

GOOD-BYE, CALIFORNIA

On the whole, in spite of “Annie Laurie’s” burdensome velvets, in spite of Mojave’s sulphur blasts and blistering sands, it had been—or, but for her mother’s illness, might have been—a happy as well as a profitable two years. Mimi and Hester Prynne had been worth while. “Wind” had been an artistic triumph.

Miss Moir, very close to Lillian during all this period, has left a series of impressions and incidents not directly connected with her work:

I remember the first time I saw her at the Ambassador Hotel, New York, she struck me as a person of perfect poise and great charm of manner in which there was something almost childishly appealing. In many ways she is a paradox. She gives the impression of helplessness when she is really the most resourceful person I know. You think sometimes that she is weak and easily led, and then you suddenly come up against an inflexible will and an iron determination to do what she has set her mind on doing.

Then another picture comes into my mind as I often saw her at parties, sitting uncomfortably in the quietest corner she could find, talking generally to some elderly person until the time came to go home, where she always went as soon as possible.

Her hands are expressive of her whole personality, delicately modelled, yet with a look of latent strength and capability about them. She uses them beautifully.

She has no fidgety movements. She is one of the few women I know who have learned the art of perfect stillness.

She loves fortune tellers, though she doesn’t take them seriously and generally forgets what they have told her, five minutes after leaving them.

Our entire life in California on looking back, seems to have its centre in the room where poor Mrs. Gish sat, patient and speechless, looking forward to the moment when Lillian would get back from the studio. On her Birthday morning her room was so crowded with presents it looked like a giftshop. She was delighted with everything, and seemed to take a turn for the better from that day. Until then she had seemed to be losing interest in life—slipping away from us. Having once aroused her from this lethargy Lillian’s whole endeavor was spent on keeping her mother amused. She was constantly coming home with some lovely thing for her—a pretty bed-jacket, a taffeta quilt for her bed, an exquisite set of china for her breakfast tray.

Mr. Mencken came for dinner one Sunday night. I remember we were all a little bit worried about entertaining such a distinguished guest, but we needn’t have been because he seemed to enjoy everything with the zest of a schoolboy.

I have somewhat different memories of the night Mr. Hergesheimer came to dine. Dinner was set for 7:30; Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks arrived, but no Mr. Hergesheimer. Half an hour and then three-quarters of an hour went by—still he did not appear. Finally the telephone rang and a desperate voice called over the wire. It was Mr. Hergesheimer: somehow or other he had gone to the house which Lillian had rented the previous year, and had been unable sooner to locate her present abode. He arrived quite out of breath, an hour late, and considerably disturbed.

One of the pleasantest recollections I have of California is the evening Lillian and I went to a “bowl” concert just a week or so before coming East for good. It was a night of brilliant moonlight, unusually warm for that climate and perfect for a concert in the open air. I remember as we drove homeward after it was all over, that we talked of our years together in California, of all the drama and comedy we had shared there, and agreed that it hadn’t been such an unpleasant time after all.

Then, presently, they were off for New York; Lillian, her Mother; the nurse, Miss Davies; Miss Moir; John, the poll-parrot, which they had got twelve years before at Denishawn; two dogs; three canary-birds, and a bus-load of hand luggage.

As usual, Lillian had worked up to the last minute, had made one or more scenes of “The Enemy” the morning of her departure. Little she guessed, when she walked out of the studio, that those were the last scenes in silent pictures she would ever make, that all unsuspected, another beautiful craft was about to be relegated to that limbo of outworn things which holds the painted panorama and the wood engraving. During fifteen years, she had been a unique figure in an industry which she had watched grow, almost from infancy, to a mighty maturity, and which was now at the moment of dissolution. That Lillian did not see this is not surprising, but that the great producers, with ears supposedly close to the ground, their research departments always alert, should have taken so little account of the warning voices (literally that), is astonishing.

Of Lillian’s pictures, I believe there are three on which her screen fame rests. In many there are distinguished scenes: in “The White Sister,” for instance; in “Romola,” in “Wind,” and in “Way Down East.” But of those which were consistently good, I should name, in order, “Broken Blossoms,” “La Bohême” and “The Scarlet Letter” as those for which she will be longest remembered: and this because of their exquisite beauty and their suitability to her special gifts.

As to what Lillian did for the picture world, I am troubled by a lack of knowledge. There are moments when it would seem that very little has been done for it, by anybody. I suspect, however, that she did more than now appears. She had a wide following among the picture players, to whom, through example alone, she must have taught restraint, delicacy—in a word, good manners. In a hundred pages I could not say more, or wish to.

X

REINHARDT

Lillian, at the Drake Hotel, in New York was kept busy declining offers of engagements—ranging from vaudeville through matrimony and pictures to the so-called legitimate stage. Maurice Maeterlinck wrote to a friend:

I should be all the more happy to undertake the scenario you speak of, in that it concerns Lillian Gish, who is the great star of the cinema that, among all, I admire, for no other has so much talent, or is so natural, so sympathetic, so moving.3

Lillian concluded a contract with the United Artists for three pictures, to be directed by Max Reinhardt, foremost director and producer of Europe. The company had a contract with Reinhardt, and it was on their promise that he should direct her, that Lillian signed with them. Her plan had had its inception a year earlier, she said, during a visit of Reinhardt’s to Los Angeles.

“My connection with Reinhardt was this: In 1923-24, I had seen his stage production of ‘The Miracle,’ with Lady Diana Manners and Rosamond Pinchot. Morris Gest brought it over, and at the time had asked me to play the part of the nun. Reinhardt, who had seen something of mine—I suppose ‘The White Sister’—had suggested this. I could not do it because of my contract. I was then on the eve of returning to Italy, to make ‘Romola.’

“I did not meet Reinhardt until he was in California, with ‘The Miracle.’ With Rudolph Kommer and Karl von Mueller he came out to our Santa Monica house, for luncheon. Before luncheon we went to the studio and ran, I think, ‘Broken Blossoms.’ Then, in the afternoon, ‘La Bohême’ and ‘The Scarlet Letter.’ They seemed to please him. He spoke no English, and I spoke no German, at the time. Kommer served as interpreter. It was then that Reinhardt suggested that we might work together. He had never made a picture, but was eager to try. He had spent thirty-five years in the theatre, and was tired of it. He had theatres in Berlin and Vienna, the finest in Europe.”

From Kansas City, Reinhardt and Kommer telegraphed:

Once more we want to thank you for that most fascinating Sunday you gave us. We greet you as the supreme emotional actress of the screen and hope fervently that the near future will bring us in closer contact on the stage and on the screen. Please do not forget Salzburg when you come to Europe. We shall be waiting for you.

Salzburg was Reinhardt’s home, where in an ancient castle, Leopoldskron, he kept open house, for a horde of congenial guests. Reinhardt and Kommer had spoken of a picture they would prepare when she came to New York. Now, at the Drake Hotel, they started on a story for it. Reinhardt, meantime, had brought over a company and was producing “Midsummer Night’s Dream” and “Danton’s Todt.”

Reinhardt, Lillian said, talked to her about Theresa Neumann, the peasant miracle girl of Konnersreuth, who on every Friday except feast days went through the entire sufferings of Christ, the blood trickling from stigmata on her forehead, her hands and her feet. Nobody but those who have seen it will believe it, but her case is a very celebrated one, and has been studied by scientists of Germany and Austria, and of other countries. Reinhardt believed that a great miracle picture could be based on the case of Theresa Neumann, and Lillian agreed with him. She would come to Leopoldskron, and would go to see Theresa Neumann for herself. “I must do that, of course,” she said, “and familiarize myself with the lives of the peasantry of which she was one.”