Полная версия:

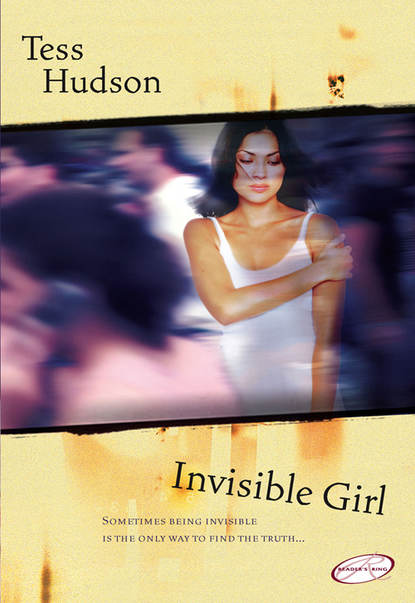

Invisible Girl

There were about forty people in the room. They applauded. Maggie felt mesmerized, and she wasn’t sure why. His voice was soothing. He looked so confident, so calm. She wanted that.

She listened to others share, thankful they ran out of time before they got to her. After the meeting, Bobby approached her.

“Um, do you want to get a cup of coffee? I usually go to a coffee shop a few blocks from here. It’s open until four in the morning.”

She smiled. “Okay.”

They walked together to the Blue Moon Diner. They didn’t say much, but the way they walked, they fell into a rhythm with each other, finding a stride. The diner had a bell that jingled over the door when they opened it. The tables had little jukeboxes on them, and they sat in a back booth. He put quarters in their jukebox and played some Elvis.

She stared at him across the table. She was pretty sure she looked like someone who’d just white-knuckled it for three days, but she was grateful Bobby hadn’t seemed to notice.

Their waitress came over, and Bobby ordered their coffee. When it came, Maggie wrapped her hands around her mug, hoping the heat would calm her.

“Much better coffee than at the meeting,” he said as he leaned into the table and smiled at her.

“You can say that again.” She sipped the coffee. “And you remembered—two sugars and lots of milk.”

“I’m a detective. I’m paid to notice details like that.” He winked at her. “How come I’ve never seen you before?”

She looked down at her coffee. “I’m…kind of quiet. I blend in.”

“You don’t blend in anywhere. I spotted you the moment you walked in.”

“Well, I go to meetings all over. I haven’t really picked a home group.”

“I almost always go to the one at St. Michael’s. And I pick up a lunchtime meeting in Manhattan sometimes.”

“A cop, huh?”

He nodded. “Does that turn you off? A lot of women just don’t want to date a cop, or even be friends with a cop. Too stressful.”

“Doesn’t bother me.”

“What do you do?”

“I’m a bartender.”

“You’re kidding.”

“Nope.”

“Isn’t that kind of hard with your sobriety?”

“Not really.” She wasn’t about to admit her “sobriety” had lasted all of three days.

“Well, I guess you must be able to twelve-step a lot of people.”

She looked at him blankly.

“You know, refer a lot of people to the program. Talk about the steps.”

“Um, yeah. Mostly I listen to people’s problems. Bartenders are paid to listen as much as pour drinks. So…do you like being a detective?”

She had a bartender’s psychology, a way of asking a question and then shutting up. Most people, she had come to discover, weren’t really looking for a bartender’s advice any more than they expected a shrink to tell them what to do. They just wanted to talk out whatever it was that was bothering them.

Sitting in the diner across from Bobby, his life story spilled out in more detail, and he told her about being a detective, about what drove him. “My best friend was shot when I was twenty-two. We were together at a bar down in lower Manhattan. He walked one way, I walked the other and went home. He ended up dead. Luck of the draw, I guess. His wallet was missing. Maybe it was a mugging gone bad. They never caught the person who did it, and I have this feeling like he’s following me all the time. Until a case is solved, that’s what ghosts do, you know. They follow you.”

“You believe in ghosts?”

He cleared his throat. “Not like seeing spirits and stuff, but I feel like the soul isn’t at rest until the case is solved. Do you believe in ghosts?”

“I think so.” She thought of her Buddhas and lighting incense and speaking to her mother. She thought of how her father was a ghost even if he was flesh and blood.

They talked—Bobby doing most of the talking—until after midnight. She found being around him comforting.

“I don’t want to say good night,” he said as he helped her from the booth. Their waitress had been sighing each time she passed their table, and they knew they’d overstayed their welcome. Maggie watched him put down a twenty-dollar tip, and as a bartender, she appreciated someone who did that. Their bill was less than nine dollars. He’d ordered a slice of pie.

“Me either. I live near here. Do you know the Twilight?”

“Rough place.”

She laughed. “I own it. Well, my father does. I live above it. If you want, I can make more coffee.” She looked at him intently, willing him to come, not sure why she was so drawn to him.

“Sure.”

When they left, a winter chill blasted them and, almost involuntarily, she leaned toward him, nearly against his arm. They walked the twelve blocks or so to the Twilight. At some point, he grabbed her hand. It was an intimate gesture, holding hands tightly, as if they were a couple.

When they got to her building, she opened the door and they climbed the stairwell to her apartment. She unlocked the door and moved to the side to let him in.

Turning on lights, she said, “I’ll make some coffee.”

“To be honest, I’m all coffeed out. If I have any more, I’ll never get to sleep.”

“Okay. Would you like a soda? Water? Juice?”

“Nah.” He took off his jacket.

“Here, I’ll put it on the coatrack.” She took his jacket from him and hung it up, placing hers on the hook next to it.

She turned around and looked at him, feeling peaceful for the first time in days, but now nervous. He walked closer to her and put his hands on either side of her face. Without saying anything, he leaned down and kissed her gently. She kissed him back.

The next thing Maggie knew, they were moving toward the bedroom. She felt as though she wanted literally to pull him inside of her, as if she wanted to hide within him, to find refuge somehow in that calm voice of his. The sex between them, even though he was a stranger to her, was incredibly intense, leaving her breathless and holding onto him.

“I wish I knew why I…I never do this,” he said. “I just felt like I knew you.”

“Me, too,” she whispered. He was in no hurry to leave. An hour later, they were making love again, and he curled himself around her, holding her tight to him as they fell asleep. She slept without Valium. She slept without dreaming, which was the point, she guessed. Dreams were always scattered, uneasy images to her.

In the morning, she rolled over and watched him sleep. There was something angelic about him, innocent. It was something missing from her father’s face, from Danny’s. The minute Bobby opened his eyes, he grinned widely. “I was hoping I wasn’t dreaming about last night.”

They stayed in bed, made love, and had coffee and eggs and read the paper.

“This is kind of crazy,” he said, sliding under the covers after breakfast and clutching her to him, her head nestling perfectly against his shoulder. “Getting involved so fast. They tell you not to do that in AA.”

“Sometimes you just know.”

She never told him she was embarking on day four without alcohol. After that night, they rarely slept apart. And Maggie rarely craved alcohol after that. Bobby was her pacifier. He was the way the night made sense.

Chapter Four

Saigon, June 11, 1963

Mai Hanh’s mother grabbed her daughter’s hand and urged her along the crowded street near the opera house. They made the trek to Saigon once a year to shop for a few items and to visit Mai’s aunt, who had left their village with a Frenchman some years before and now lived in an apartment that Mai thought smelled of a strange mixture of clove cigarettes and dumplings.

The streets were filled with pedestrians, and Mai frequently bumped into people as her mother tugged and pulled, demanding her to walk faster than her ten-year-old legs could carry her.

Ahead of them, an enormous gathering of people stood, blocking the way, as they formed a circle. Mai couldn’t see what was going on, but she heard chanting.

“Ma, what is it?”

Her mother, who usually walked with her head bent forward and down, as if expecting to confront a strong wind, lifted her face. Mai noticed how tired her mother appeared. She was always tired when they visited Tante, as her aunt insisted Mai call her. Tante wore a silk dress the color of emeralds, stiletto heels and stockings with a black seam down the leg, red lipstick, her hair in intricate braids with tortoiseshell combs. Ma wore plain black pants and a loose top, both made of coarse cloth and flat black cloth shoes. Ma never wore lipstick, didn’t own lipstick, and the years of working in the fields had taken their toll on her hands and the skin on her face.

“I don’t know,” Ma said.

Mai craned her neck but saw nothing but the backs of the people in her way. Then she decided to crouch. From her new vantage point, she could glimpse the center of the circle. Crouching further still, she saw Buddhist monks and nuns. They were speaking about charity and compassion.

“What is it?” Ma asked, looking down at Mai.

“I don’t know. Monks.” Mai squinted as an elderly monk with a smooth face sat down, his saffron robes gleaming in the midday sun, his eyes serene and determined. The nuns and monks around him were speaking, reciting from books, but Mai couldn’t make out what they were saying. The sitting monk remained calm. Tranquil. Mai watched as they poured a liquid on his robes and then his head. Something was shouted from the crowd and she heard a scream.

The sitting monk set himself on fire. They had been pouring gasoline, Mai realized as the intense smell of burning flesh assaulted her nostrils.

“Ma!” She grabbed at her mother’s legs and clung to her, unable to look away from the image of the burning holy man, waves of nausea sweeping over her as her stomach fell and shuddered.

“What is it, Little Mai?”

“He’s on fire, Ma.”

Her mother quickly swooped Mai into her arms, though Mai was too big to be held like that anymore, and her spindly legs trailed down her mother’s body. Protectively, her mother pushed Mai’s face against her shoulder, forcing Mai to look away.

“Why, Ma?” Mai cried, tears rolling down her face.

Her mother shook her head. “Vietnam is like grain that the hens peck. First this one wants her, then that. France, America. Pecking at us. Pecking.”

The crowd had grown restless and angry over the immolation. Mai’s mother insistently pushed and maneuvered until they were down a side street, moving away from the commotion.

Later that night, Mai tried to sleep. But in the flames of the cooking fire, she kept seeing the monk. She wondered if Buddha had given him the courage. Because even as he’d burned to death, the monk her mother said was named Thich Quang Due had never flinched. He had burned alive without moving a muscle, without uttering a single cry of agony.

Chapter Five

Sometime near dawn, Maggie watched as her brother stirred. She crossed the room to his side and knelt down.

“Danny?”

“Hey,” he said, squinting up at her, his voice hoarse and gravelly.

“Want a sip of water?”

“I’ll take a shot of J. D. if you have it,” he said as he winked his good eye.

“No, you won’t. I’ll get you some water.”

She stood and went to the kitchen, returning with a small glass of ice water. She helped Danny lean up on the elbow of his good arm so he could take a sip.

“Hope I didn’t scare you too much.”

“I’m used to it by now.”

“Yeah, but last time you told the old man and me you’d had enough of this bullshit.”

“I was angry. Forget about that. How do you feel?”

Danny leaned back down on the mattress and felt along his face, his fingers tracing the ragged line of the home-sewn stitches. “I bet as bad as I look. Even my eyelashes hurt, bright eyes. My earlobes hurt. There’s nothing on me that doesn’t hurt.”

“Want some more Tylenol with codeine?”

“Yeah. But I better eat something with it. Toast.”

“How’s the arm?”

“I don’t know. I’m not sure if it’s broken.”

“I think it was just a dislocated shoulder. I hope it was, at least. You going to tell me what happened?”

“Damned if I know.”

“Come off it, Danny.”

“I’m serious. Three guys came into the warehouse we got out in Jersey. I was just getting ready to lock up. From the looks of them, I knew they didn’t want a pirated DVD.”

“Have you ever seen them before?”

He moved his head very slowly from side to side.

“You owe any money around?”

“I’ve been laying off the betting. Nothing. I got a bad feeling as soon as they walked in, and I started to walk toward the desk, where I keep a gun in the top drawer. One of them, a huge cement wall of a guy, blocked my way.”

Maggie winced. “Christ, I know where this is going.”

“Exactly. They locked the door and beat the living shit out of me. I put up a fight. Smashed a chair on somebody’s head. But three guys, Mags. I didn’t stand a chance.”

“And did they tell you what they wanted?”

“No. They just kept saying I knew what they wanted, which I didn’t. They flipped the warehouse from end to end. Went through my lockbox. They didn’t take the cash or find what they were looking for, either. They left me half-dead on the floor and said they’d let me think about it, and that they’d be back. I barely remember getting up and driving here.”

Maggie’s teeth started chattering from nerves and she pulled her knees close to her chest as she sat on the floor. “You have no idea who they were?”

“No. But they mentioned Dad. And from how they looked…you know the type.”

“Christ, what is he into this time?”

“I have no idea, and if we don’t figure it out, I’m a dead man. And frankly, I’m not too sure you’re safe, either.”

Bobby Gonzalez’s deep voice called out from the bedroom doorway behind them. “What do you mean Maggie’s not safe?”

Maggie startled and whipped her head around, and then she turned back and exchanged a look with Danny.

“Listen, if you two are in trouble, I can help.”

“Maggie told me you’re a cop. And cops, in general, don’t help the kind of trouble we’re in,” Danny said.

“And what kind of trouble is that?”

Danny glanced at Maggie. “It has to do with our father.”

“So ask him. Whatever these guys wanted, find out what it is and give it to them.”

“We can’t ask Dad.” Maggie didn’t look directly at Bobby. “We don’t know where he is. He took off over a year ago. He wouldn’t say why. Said it would be safer if we didn’t know where he was. We didn’t ask questions.”

“What kind of father leaves his kids in danger like that?”

“We’re not kids. We can take care of ourselves,” Maggie snapped.

“As evidenced by you having to stitch your brother up last night? Look, if you don’t want to report this, fine, but I hope you have a better plan than sitting here waiting to be killed for whatever it is these jerks wanted last night. What’d these guys look like anyway?”

Maggie saw the answer in Danny’s eyes before he even said anything.

“Feds,” he whispered.

“What was that?” Bobby came closer to the two of them. Instinctively, Maggie touched Danny, as if he were a talisman of reassurance. She fingered his shirtsleeve, almost absentmindedly.

“Feds,” Danny said again, louder this time.

“I don’t get it. What are feds doing beating the crap out of you?”

“Whatever our father did in Laos,” Maggie said, “he had friends in high places.” She paused. “And enemies in even higher places.”

“So we put out feelers. I can find someone to trust in the bureau. We can get to the bottom of this discreetly, put you into protective custody if we have to.”

“You don’t get it, pretty boy,” Danny said, shutting his eyes. “You won’t find our father anywhere in the bureau, or anywhere, period. He doesn’t exist.”

Bobby looked at Maggie, who nodded in agreement. “You could reach out all you want, Bobby. He doesn’t exist. He’s a phantom, and by birthright, so are we.”

Maggie watched as Bobby’s eyes revealed a struggle to understand. He paced back and forth a few times before he turned back to them. “I don’t accept that you’re just going to stay here and wait for them. You have to be able to do something.”

“We can call Uncle Con,” Maggie suggested.

“Who’s he?”

“Our father’s best friend,” Danny replied.

“And he’ll know where your father is?”

“Maybe. We have another uncle, Dad’s brother. He lives in Boston. But Con is more likely to know where he is.”

“What’s Con short for? Conrad?”

“No. Con artist.”

“This just gets better and better.”

Maggie got up to go make Danny some toast. As she neared the kitchen, Bobby approached her. “Can we talk in private?” he asked.

She followed him into the bedroom and shut the door.

“Are you out of your mind?” he asked her.

“No.”

“What’s going on?”

“I don’t know.”

“You have no idea?”

She sat on the bed. “From time to time, men would come to the Twilight. They looked like CIA. Feds. I didn’t ask questions. Then maybe two or three years ago, things started to seem dangerous. I can’t put my finger on it, but my father changed. He began moving things to safety deposit boxes. Became paranoid, which wasn’t like him. Maybe paranoid isn’t the right word…just very secretive.”

“Sounds like the guy was already pretty damn secretive.”

“This was worse. Then he took off.”

“Just like that?”

“In a way, yes.” She looked up at Bobby, aware for the thousandth time since their first night together that he was good in a way the shadowy world of her father would never be.

“I don’t know what to say, Maggie. Let’s call this uncle Con of yours and see what he thinks.”

Maggie went to the phone, then thought better of it, not wanting to use her land line. “Can I use your cell?”

Bobby picked up the phone, which was next to his wallet on the dresser. He handed it to her.

Maggie dialed the number, praying Con would answer even if he didn’t recognize Bobby’s number on caller ID.

“Yeah.” His voice came over the line in the vaguely hostile way he had of answering the telephone.

“Con, it’s Maggie.”

“Oh, bright eyes, I’m so sorry.”

“You heard about Danny?”

“Danny? No. Don’t tell me those fucking bastards got to him, too?”

“Too?”

“Is he dead or alive?”

“Alive, but just barely. What are you talking about Con?” Fear seeped into her voice and around the edges of her brain. Bobby came and stood behind her, pulling her backward against his chest and wrapping his arms around her.

“Your father, Maggie. I thought you knew.”

“Knew what?” she asked, but felt the answer down in her stomach, in the way it tightened.

“He’s dead. The bastards finally got him.”

Chapter Six

Somewhere near the seventeenth parallel, North Vietnam, July 1972

Our Father who art in heaven…

Jimmy Malone was surprised at how quickly the words leaped to his tongue. The short one, the one with the bad teeth, kept poking at Jimmy’s broken arm. Tears of pain filled his eyes. The short one poked harder, his finger touching bone through the deep gash that ran from Jimmy’s elbow to his shoulder. The short one said something unintelligible to the taller one with the lazy left eye, and without even knowing their language, Jimmy could tell they were angry.

Bile rose in his throat. Six months ago, out of shame or politeness, he would have turned his head. Now, sweating in the jungle, insects swarming around his eyes, making blinking a necessity to ward off insanity, he merely leaned forward and retched from the pain. He felt his own vomit warm the front of his shirt.

Hallowed be thy name…

The prayer was there. On the edge of his consciousness. He repeated it over and over in his mind. A mental salve on the open sore of being twenty-two and hopelessly bent and broken in a jungle farther from New York’s west side than he had ever imagined he might go. Farther than he’d ever wanted to go.

Thy kingdom come…

Sometimes Jimmy thought about the words.

Thy will be done…

How could this be God’s will? This war, his arm, the short one with the bad teeth. The hunger. The bugs. The fucking bugs. God, how can this be your will? Death. Cowboy McMann blown to smithereens right in front of him. The land mines. The bugs. The infection spreading up his arm. Malaria. In two days, I will be dead. If I make it that long. God’s will. Jimmy wanted to weep, but that wasn’t how he was raised—his father would have just as soon punched him in the face than allow a son of his to cry. His mother was the same, a tough old woman, always a bourbon away from passing out.

On earth as it is in Heaven…

Hell. Fucking hell. Hot as hell. That’s what this place is, he thought through the pain, so intense at times he thought he was floating above himself. When had the short one left? He couldn’t remember. It all ran together. Day and night. Bugs and stickiness and pain and bugs all the time. Same day. Different day. All the same.

And lead us not into temptation…

And sometimes he didn’t think about the words but just the sound of them. Like a mantra, he repeated the prayer. I am still alive. I am still alive. Our Father. Our Father. Our Father. I am still alive. Not that he was sure being alive was a good thing. Dying far from home on the floor of a hut, gooks poking him, swollen mosquitoes too fat to fly from drinking the blood clustered on his wound. Young North Vietnamese—no more than boys—hitting him with sticks. All he could think of was relief. Death or rescue. One way or the other. Relief.

But deliver us from evil…

And that line, when he thought about it, was for the Washington assholes. The politicians whose own sons would never see the war, or if they did, it’d be as paper-pushers somewhere. Fucking evil motherfuckers. You come die here.

Amen… Fucking evil.

He tried to imagine the antithesis of evil. He thought of Mai. He had a rule when he was flying. He wasn’t allowed to think of her. Men died when they let down their guard, fragments of thoughts of home or their girl making them careless. Instead, he put Mai in a box in his mind. Then, when it was time, when he was on the ground, when he was safe, he would shut his eyes and open the box and take her out.

Their moments together were rare. It was hard to get away, to get to her village. And she came to Saigon infrequently. But when he saw her, Vietnam was bearable. He couldn’t believe he was content to do as little as hold her hand. But he was. He liked to bring her things to make her smile. An American camera, candies, bottles of Coca-Cola, a Timex watch. He kept a picture of her inside his helmet. Mai. His Mai. She was smiling at him in the picture, sunlight on her face. He would look at her photo and almost forget the war. Maybe what she said about Buddha and reincarnation was true. Maybe he’d known her in another life.

He hoped she was safe. Mai’s father was dead. Killed a year ago. Determined to keep Mai from harm, Jimmy had brought some buddies and they’d dug a hiding spot big enough for her and her mother and baby sister in case their village was raided. Between the hiding spot and the money Jimmy was able to give Mai, he’d even won over her mother. He wished this fucking war would be over and he could bring them all to America.

Jimmy thought of Mai and the pain eased a tiny bit, replaced by an ache in his heart. He would never see her again. Sometime between dusk and dawn, in the darkness, the rats came. He named the first one, a fat son of a bitch, Cass, after Mama Cass, and he felt a twinge of pride at his bravado. Humor in the face of an amazingly hopeless situation. When the second and third and fourth rats showed up, a tidal rush of pity and fear swept over him. Cass bit his ankle. A second prayer entered his mind.