Полная версия

Полная версияLouisa May Alcott : Her Life, Letters, and Journals

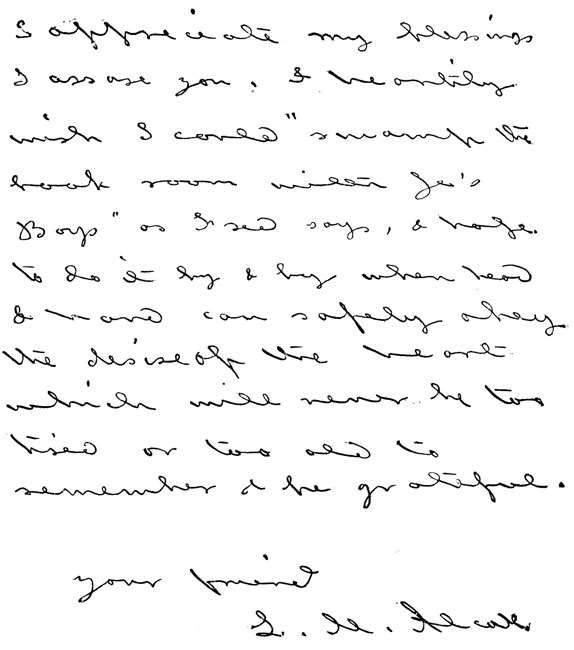

Fac-simile of Miss Alcott's Writing.

I'd like to help Mrs. L. if I could, as we know something of her, and I fancy she needs a lift. Perhaps we could use these pictures in some way if she liked to have us. Maybe I could work them into a story of out "cullud bredren."

Thanks for the books. Dear Miss – is rather prim in her story, but it is pretty and quite correct. So different from Miss Alcott's slap-dash style.

The "H. H." book ["Ramona"] is a noble record of the great wrongs of her chosen people, and ought to wake up the sinners to repentance and justice before it is too late. It recalls the old slavery days, only these victims are red instead of black. It will be a disgrace if "H. H." gave her work and pity all in vain.

Yours truly,L. M. A.[1885.]Dear Mr. Niles,–Thanks for the book which I shall like to read.

Please tell Miss N. that she will find in Sanborn's article in "St. Nicholas" or Mrs. Moulton's in the "Eminent Women" book all that I wish to have said about myself. You can add such facts about editions, etc., as you think best. I don't like these everlasting notices; one is enough, else we poor people feel like squeezed oranges, and nothing is left sacred.

George Eliot's new life and letters is well done, and we are not sorry we have read them. Mr. Cross has been a wise man, and leaves us all our love and respect instead of spoiling them as Froude did for Carlyle,

Yours truly,L. M. A.January 2, 1886.Dear Mr. Niles,–Thanks for the good wishes and news. Now that I cannot work, it is very agreeable to hear that the books go so well, and that the lazy woman need not worry about things.

I appreciate my blessings, I assure you. I heartily wish I could "swamp the book-room with 'Jo's Boys,'" as Fred says, and hope to do it by and by when head and hand can safely obey the desire of the heart, which will never be too tired or too old to remember and be grateful.

Your friend,L. M. Alcott.Monday, a. m. [1886].Dear Mr. Niles,–My doctor forbids me to begin a long book or anything that will need much thought this summer. So I must give up "Tragedy of To-day," as it will need a good deal of thinking to be what it ought.

I can give you a girls' book however, and I think that will be better than a novel. I have several stories done, and can easily do more and make a companion volume for "Spinning-Wheel Stories" at Christmas if you want it.

This, with the Lulu stories, will be better than the set of novels I am sure… Wait till I can do a novel, and then get out the set in style, if Alcott is not forgotten by that time.

I was going to send Mrs. Dodge one of the tales for girls, and if there is time she might have more. But nearly all new ones would make a book go well in the holiday season. You can have those already done now if you want them. "Sophie's Secret" is one, "An Ivy Spray: or Cinderella's Slippers" another, and "Mountain Laurel" is partly done. "A Garland for Girls" might do for a title perhaps, as they are all for girls.

Yours truly,L. M. A.In the spring of 1886, Dr. Rhoda Lawrence took charge of Miss Alcott's health, and gave her treatment by massage and other appropriate means, from which she received benefit. The summer was spent at Concord with her father, and was varied by a pleasant trip to the mountains. Miss Alcott finished "Jo's Boys," which was published in September. She occupied herself also in looking over old journals and letters, and destroyed many things which she did not wish to have come under the public eye. She had enjoyed her life at Princeton, and said that she felt better than for fifteen years; but in August she was severely attacked with rheumatism and troubled with vertigo. She suffered very much, and was in a very nervous condition.

Miss Alcott always looked bravely and calmly upon all the possibilities of life, and she now made full preparations for the event of her own death. Her youngest nephew had always been especially beloved, and she decided to take out papers of adoption, to make him legally her son and heir. She wished him to assume the name of Alcott, and to be her representative.

Louisa's journal closes July, 1886, with the old feeling,–that she must grind away at the mill and make money to supply the many claims that press upon her from all sides. She feels the burden of every suffering human life upon her own soul. She knew that she could write what was eagerly desired by others and would bring her the means of helping those in need, and her heart and head united in urging her to work. Whether it would have been possible for her to have rested more fully, and whether she might then have worked longer and better, is one of those questions which no one is wise enough to answer. Yet the warning of her life should not be neglected, and the eager brain should learn to obey the laws of life and health while it is yet time.

In September, 1886, Miss Alcott returned to Louisburg Square, and spent the winter in the care of her father, and in the society of her sister and nephews and the darling child. She suffered much from hoarseness, from nervousness and debility, and from indigestion and sleeplessness, but still exerted herself for the comfort of all around her. She had a happy Christmas, and sympathized with the joy of her oldest nephew in his betrothal. In December she was so weary and worn that she went out to Dr. Lawrence's home in Roxbury for rest and care. She found such relief to her overtasked brain and nerves from the seclusion and quiet of Dunreath Place, that she found her home and rest there for the remainder of her life.

It was a great trial to Louisa to be apart from her family, to whom she had devoted her life. She clung to her dying father, and to the dear sister still left to her, with increasing fondness, and she longed for her boys and her child; but her tired nerves could not bear even the companionship of her family, and sometimes for days she wanted to be all alone. "I feel so safe out here!" she said once.

Mr. Alcott spent the summer at Melrose, and Louisa went there to visit him in June. In June and July, 1887, she went to Concord and looked over papers and completed the plan for adopting her nephew. She afterward went to Princeton, accompanied by Dr. Lawrence. She spent eight weeks there, and enjoyed the mountain air and scenery with something of her old delight. She was able to walk a mile or more, and took a solitary walk in the morning, which she greatly enjoyed. Her evening walk was less agreeable, because she was then exposed to the eager curiosity of sight-seers, who constantly pursued her.

Miss Alcott had a great intellectual pleasure here in the society of Mr. James Murdock and his family. The distinguished elocutionist took great pains to gratify her taste for dramatic reading by selecting her favorite scenes for representation, and she even attended one of his public readings given in the hall of the hotel. The old pain in her limbs from which she suffered during her European journey again troubled her, and she returned to Dr. Lawrence's home in the autumn, where she was tenderly cared for.

Miss Alcott was still continually planning stories. Dr. Lawrence read to her a great deal, and the reading often suggested subjects to her. She thought of a series to be called "Stories of All Nations," and had already written "Trudel's Siege," which was published in "St. Nicholas," April, 1888, the scene of which was laid at the siege of Leyden. The English story was to be called "Madge Wildfire," and she had thought of plots for others. She could write very little, and kept herself occupied and amused with fancy work, making flowers and pen-wipers of various colors, in the form of pinks, to send to her friends.

On her last birthday Louisa received a great many flowers and pleasant remembrances, which touched her deeply, and she said, "I did not mean to cry to-day, but I can't help it, everybody is so good." She went in to see her father every few days, and was conscious that he was drawing toward the end.

While riding with her friend, Louisa would tell her of the stories she had planned, one of which was to be called "The Philosopher's Wooing," referring to Thoreau. She also had a musical novel in her mind. She could not be idle, and having a respect for sewing, she busied herself with it, making garments for poor children, or helping the Doctor in her work. She insisted upon setting up a work-basket for the Doctor, amply supplied with necessary materials, and was pleased when she saw them used. A flannel garment for a poor child was the last work of her hands. Her health improved in February, especially in the comfort of her nights, as the baths she took brought her the long-desired sleep. "Nothing so good as sleep," she said. But a little too much excitement brought on violent headaches.

During these months Miss Alcott wrote part of the "Garland for Girls," one of the most fanciful and pleasing of her books. These stories were suggested by the flowers sent to her by different friends, which she fully enjoyed. She rode a great deal, but did not see any one.

Her friends were much encouraged; and although they dared not expect full recovery, they hoped that she might be "a comfortable invalid, able to enjoy life, and give help and pleasure to others." She did not suffer great pain, but she was very weak; her nervous system seemed to be utterly prostrated by the years of work and struggle through which she had passed. She said, "I don't want to live if I can't be of use." She had always met the thought of death bravely; and even the separation from her dearest friends was serenely borne. She believed in their continued presence and influence, and felt that the parting was for a little time. She had no fear of God, and no doubt of the future. Her only sadness was in leaving the friends whom she loved and who might yet need her.

A young man wrote asking Miss Alcott if she would advise him to devote himself to authorship; she answered, "Not if you can do anything else. Even dig ditches." He followed her advice, and took a situation where he could support himself, but he still continued to write stories. A little boy sent twenty-five cents to buy her books. She returned the money, telling him it was not enough to buy books, but sent him "Little Men." Scores of letters remained unanswered for want of strength to write or even to read.

Early in March Mr. Alcott failed very rapidly. Louisa drove in to see him, and was conscious that it was for the last time. Tempted by the warm spring-like day, she had made some change in her dress, and absorbed in the thought of the parting, when she got into the carriage she forgot to put on the warm fur cloak she had worn.

The next morning she complained of violent pain in her head, amounting to agony. The physician who had attended her for the last weeks was called. He felt that the situation was very serious. She herself asked, "Is it not meningitis?" The trouble on the brain increased rapidly. She recognized her dear young nephew for a moment and her friendly hostess, but was unconscious of everything else. So, at 3.30 p. m., March 6, 1888, she passed quietly on to the rest which she so much needed. She did not know that her father had already preceded her.

The friends of the family who gathered to pay their last tribute of respect and love to the aged father were met at the threshold by the startling intelligence, "Louisa Alcott is dead," and a deeper sadness fell upon every heart. The old patriarch had gone to his rest in the fulness of time, "corn ripe for the sickle," but few realized how entirely his daughter had worn out her earthly frame. Her friends had hoped for renewed health and strength, and for even greater and nobler work from her with her ripened powers and greater ease and leisure.

Miss Alcott had made every arrangement for her death; and by her own wish the funeral service was very simple, in her father's rooms at Louisburg Square, and attended only by a few of her family and nearest friends. They read her exquisite poem to her mother, her father's noble tribute to her, and spoke of the earnestness and truth of her life. She was remembered as she would have wished to be. Her body was carried to Concord and placed in the beautiful cemetery of Sleepy Hollow where her dearest ones were already laid to rest. "Her boys" went beside her as "a guard of honor," and stood around as she was placed across the feet of father, mother, and sister, that she might "take care of them as she had done all her life."

Of the silent grief of the bereaved family I will not speak, but the sound of mourning filled all the land, and was re-echoed from foreign shores. The children everywhere had lost their friend. Miss Alcott had entered into their hearts and revealed them to themselves. In her childish journal her oldest sister said, "I have not a secret from Louisa; I tell her everything, and am not afraid she will think me silly." It was this respect for the thought and life of children that gave Louisa Alcott her great power of winning their respect and affection. Nothing which was real and earnest to them seemed unimportant to her.

LAST LETTERSTo Mr. NilesSunday, 1886.Dear Mr. Niles,–The goodly supply of books was most welcome; for when my two hours pen-work are over I need something to comfort me, and I long to go on and finish "Jo's Boys" by July 1st.

My doctor frowns on that hope, and is so sure it will do mischief to get up the steam that I am afraid to try, and keep Prudence sitting on the valve lest the old engine run away and have another smash-up.

I send you by Fred several chapters, I wish they were neater, as some were written long ago and have knocked about for years; but I can't spare time to copy, so hope the printers won't be in despair.

I planned twenty chapters and am on the fifteenth. Some are long, some short, and as we are pressed for time we had better not try to do too much.

… I have little doubt it will be done early in July, but things are so contrary with me I can never be sure of carrying out a plan, and I don't want to fail again; so far I feel as if I could, without harm, finish off these dreadful boys.

Why have any illustrations? The book is not a child's book, as the lads are nearly all over twenty, and pretty pictures are not needed. Have the bas-relief if you like, or one good thing for frontispiece.

I can have twenty-one chapters and make it the size of "Little Men." Sixteen chapters make two hundred and sixteen pages, and I may add a page here and there later,–or if need be, a chapter somewhere to fill up.

I shall be at home in a week or two, much better for the rest and fine air; and during my quiet days in C. I can touch up proofs and confer about the book. Sha'n't we be glad when it is done?

Yours truly,L. M. A.To Mrs. DodgeJune 29.Dear Mrs. Dodge,–I will evolve something for December (D. V.) and let you have it as soon as it is done.

Lu and I go to Nonquit next week; and after a few days of rest, I will fire up the old engine and see if it will run a short distance without a break-down.

There are usually about forty young people at N., and I think I can get a hint from some of them.

Had a call from Mr. Burroughs and Mr. Gilder last eve. Mr. G. asked if you were in B., but I didn't know.

Father remains comfortable and happy among his books. Our lads are making their first visit to New York, and may call on "St. Nick," whom they have made their patron saint.

I should like to own the last two bound volumes of "St. Nicholas," for Lulu. She adores the others, and they are nearly worn out with her loving but careless luggings up and down for "more towries, Aunt Wee-wee." Charge to

Yours affectionately,L. M. A.P. S.–Wasn't I glad to see you in my howling wilderness of wearisome domestic worrits! Come again.

Concord, August 15.Dear Mrs. Dodge,–I like the idea of "Spinning-Wheel Stories," and can do several for a series which can come out in a book later. Old-time tales, with a thread running through all from the wheel that enters in the first one.

A Christmas party of children might be at an old farm-house and hunt up the wheel, and grandma spins and tells the first story; and being snow-bound, others amuse the young folks each evening with more tales. Would that do? The mother and child picture would come in nicely for the first tale,–"Grandma and her Mother."

Being at home and quiet for a week or so (as Father is nicely and has a capable nurse), I have begun the serial, and done two chapters; but the spinning-tales come tumbling into my mind so fast I'd better pin a few while "genius burns." Perhaps you would like to start the set Christmas. The picture being ready and the first story can be done in a week, "Sophie's Secret" can come later. Let me know if you would like that, and about how many pages of the paper "S. S." was written on you think would make the required length of tale (or tail?). If you don't want No. 1 yet, I will take my time and do several.

The serial was to be "Mrs. Gay's Summer School," and have some city girls and boys go to an old farm-house, and for fun dress and live as in old times, and learn the good, thrifty old ways, with adventures and fun thrown in. That might come in the spring, as it takes me longer to grind out yarns now than of old.

Glad you are better. Thanks for kind wishes for the little house; come and see it, and gladden the eyes of forty young admirers by a sight of M. M. D. next year.

Yours affectionately,L. M. A.31 Chestnut St., December 31.Dear Mrs. Dodge,–A little cousin, thirteen years old, has written a story and longs to see it in print. It is a well written bit and pretty good for a beginner, so I send it to you hoping it may find a place in the children's corner. She is a grandchild of S. J. May, and a bright lass who paints nicely and is a domestic little person in spite of her budding accomplishments. Good luck to her!

I hoped to have had a Christmas story for some one, but am forbidden to write for six months, after a bad turn of vertigo. So I give it up and take warning. All good wishes for the New Year.

From yours affectionately,L. M. Alcott.To Mr. Niles1886.Dear Mr. Niles,–Sorry you don't like the bas-relief [of herself]; I do. A portrait, if bright and comely, wouldn't be me, and if like me would disappoint the children; so we had better let them imagine "Aunt Jo young and beautiful, with her hair in two tails down her back," as the little girl said.

In haste,L. M. A.To Mrs. BondConcord, Tuesday, 1886.Dear Auntie,–I want to find Auntie Gwinn, and don't know whom to ask but you, as your big motherly heart yearns over all the poor babies, and can tell them where to go when the nest is bare. A poor little woman has just died, leaving four children to a drunken father. Two hard-working aunts do all they can, and one will take the oldest girl. We want to put the two small girls and boy into a home till we can see what comes next. Lulu clothes one, and we may be able to put one with a cousin. But since the mother died last Wednesday they are very forlorn, and must be helped. If we were not so full I'd take one; but Lu is all we can manage now.

There is a home at Auburndale, but it is full; and I know of no other but good Auntie Gwinn's. What is her address, please? I shall be in town on Saturday, and can go and see her if I know where.

Don't let it be a bother; but one turns at once in such cases to the saints for direction, and the poor aunts don't known what to do; so this aunt comes to the auntie of all.

I had a pleasant chat with the Papa in the cars, and was very glad to hear that W. is better. My love to both and S.

Thanks for the news of portraits. I'll bear them in mind if G. H. calls. Lulu and Anna send love, and I am as always,

YourLouisa Alcott.To Mrs. DodgeApril 13, 1880.Dear Mrs. Dodge,–I am glad you are going to have such a fine outing. May it be a very happy one.

I cannot promise anything, but hope to be allowed to write a little, as my doctor has decided that it is as well to let me put on paper the tales "knocking at the saucepan lid and demanding to be taken out" (like Mrs. Cratchit's potatoes), as to have them go on worrying me inside. So I'm scribbling at "Jo's Boys," long promised to Mr. Niles and clamored for by the children. I may write but one hour a day, so cannot get on very fast; but if it is ever done, I can think of a serial for "St. Nicholas." I began one, and can easily start it for '88, if head and hand allow. I will simmer on it this summer, and see if it can be done. Hope so, for I don't want to give up work so soon.

I have read "Mrs. Null," but don't like it very well,–too slow and colorless after Tolstoi's "Anna Karanina."

I met Mr. and Mrs. S. at Mrs. A.'s this winter. Mr. Stockton's child-stories I like very much. The older ones are odd but artificial.

Now, good-by, and God be with you, dear woman, and bring you safely home to us all.

Affectionately yours,L. M. Alcott.To Mrs. BondDunreath Place, Roxbury, March 15, 1887Dear Auntie,–I have been hoping to get out and see you all winter, but have been so ill I could only live on hope as a relish to my gruel,–that being my only food, and not of a nature to give me strength. Now I am beginning to live a little, and feel less like a sick oyster at low tide. The spring days will set me up I trust, and my first pilgrimage shall be to you; for I want you to see how prettily my May-flower is blossoming into a fine off-shoot of the old plant.

Lizzy Wells has probably told you our news of Fred and his little bride, and Anna written you about it as only a proud mamma can.

Father is very comfortable, but says sadly as he looks up from his paper, "Beecher has gone now; all go but me." Please thank Mr. Bond for the poems, which are interesting, even to a poor, ignorant worm who does not know Latin. Mother would have enjoyed them very much. I should have acknowledged his kindness sooner; but as I am here in Roxbury my letters are forwarded, and often delayed.

I was sorry to hear that you were poorly again. Isn't it hard to sit serenely in one's soul when one's body is in a dilapidated state? I find it a great bore, but try to do it patiently, and hope to see the why by and by, when this mysterious life is made clear to me. I had a lovely dream about that, and want to tell it you some day.

Love to all.

Ever yours,L. M. A.Her publisher wished to issue a new edition of "A Modern Mephistopheles," and to add to it her story "A Whisper in the Dark," to which she consented.

May 6, 1887.Dear Mr. Niles.–This is about what I want to say. You may be able to amend or suggest something. I only want it understood that the highfalutin style was for a disguise, though the story had another purpose; for I'm not ashamed of it, and like it better than "Work" or "Moods."

Yours in haste,L. M. A.P. S.–Do you want more fairy tales?

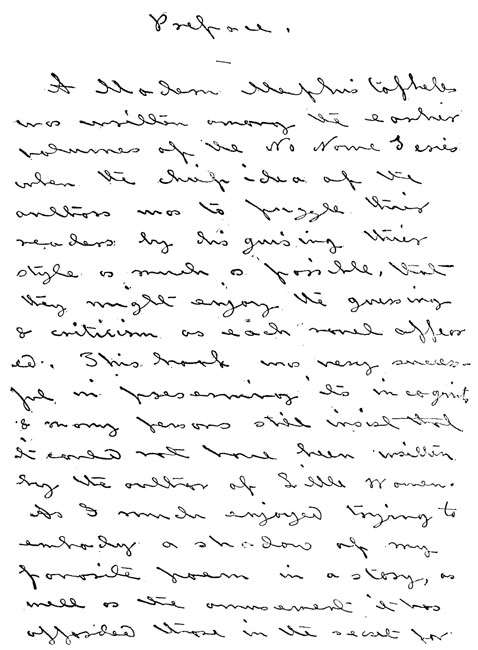

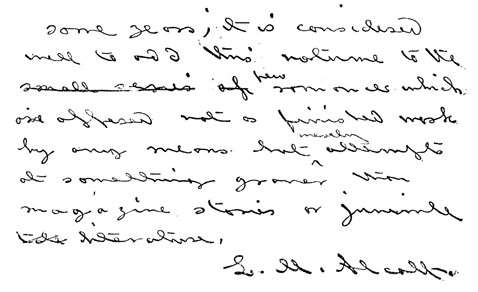

Preface"A Modern Mephistopheles" was written among the earlier volumes of the No Name Series, when the chief idea of the authors was to puzzle their readers by disguising their style as much as possible, that they might enjoy the guessing and criticism as each novel appeared. This book was very successful in preserving its incognito; and many persons still insist that it could not have been written by the author of "Little Women." As I much enjoyed trying to embody a shadow of my favorite poem in a story, as well as the amusement it has afforded those in the secret for some years, it is considered well to add this volume to the few romances which are offered, not as finished work by any means, but merely attempts at something graver than magazine stories or juvenile literature.

L. M. Alcott.

Fac-simile of Preface to "A Modern Mephistopheles."

Saturday a.m., May 7, 1887.

Dear Mr. Niles,–Yours just come. "A Whisper" is rather a lurid tale, but might do if I add a few lines to the preface of "Modern Mephistopheles," saying that this is put in to fill the volume, or to give a sample of Jo March's necessity stories, which many girls have asked for. Would that do?