Полная версия

Полная версияRoyal Edinburgh: Her Saints, Kings, Prophets and Poets

"When the Earl of Ross's wyff understood the King to be some pairt favourable to all that sought his grace she fled also under his protection to eschew the cruel tyranny of her husband, which she dreaded sometyme before. The King called to remembrance that this woman was married not by her own counsel to Donald of the Isles (the Earl of Ross). He gave her also sufficient lands and living whereon she might live according to her estate."

The case of women, and especially heiresses, in that lawless age must have been miserable indeed. Bandied about from one marriage to another, forced to accept such security as a more or less powerful lord could give, and when he was killed to fall victim to the next who could seize upon her, or to whom she should be allotted by feudal suzerain or chieftain, the mere name of a king who did not disdain a woman's plaint, but had compassion and help to give, must have conveyed hope to many an unhappy lady bound to a repugnant life. James would seem to have been the only man who recognised the misery to which such unconsidered items in the wild and tumultuous course of affairs might be driven.

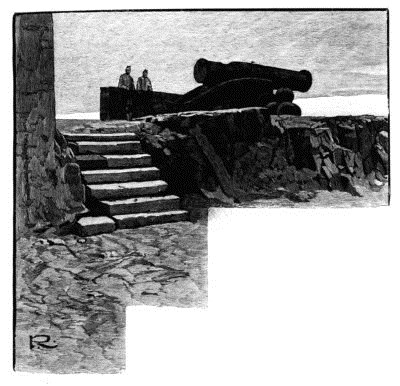

Thus King James and Scotland with him were delivered from the greatest and most dangerous of the powerful houses that held the country in fear. Shortly after he conquered, partly by arms, partly by the strain of a universal impulse, which seemed to rouse the barons to a better way, those great allies in the north who held the key of the Highlands, the Earl of Crawford and the Earl of Ross, so that at last something of a common rule and common sentiment began to move the country. It is almost needless to say that James took advantage of this temporary unity and enthusiasm in order to invade England—a thing without which no Scots King could be said to be happy. The negotiations by which he was at once stimulated and hindered—among others by ambassadors from the Duke of York to ask his help against Henry VI, with orders to arrest his army on their way—are too complicated to be entered upon; but at last the Scots forces set out and, after various successes, James found himself before Roxburgh, a town and castle which had remained in the hands of the English from the time when the Earl of March deserted his country for England in the reign of Robert III. The town was soon taken, but the castle, in which there was a brave garrison, stood out manfully. This invasion of the Borders, and opportunity of striking a blow at the "auld enemy," was evidently an act of the highest policy while yet the surgings of civil war were not entirely quieted, and a diversion of ideas as well as new opportunities of spoil were peculiarly necessary. Its first excellent result was that Donald of the Isles, the Earl of Ross and terror of the north country, whose submission had been but provisionally accepted, and depended upon some evidence of real desire for the interest of the common weal, suddenly appeared with "ane great armie of men, all armed in the Highland fashion," and claimed the vanguard, the place of honour, and to be allowed to take upon him "the first press and dint of the battell." James received this unexpected auxiliary with "great humanitie," but prudently provided, before accepting his offer, which apparently, however, was made in all good faith, that Donald should "stent his pavilliones a little by himself," until full counsel had been taken on the subject. The army was also joined by "a great company of stout and chosen men," under the Earl of Huntly, whose coming "made the King so blyth that he commanded to charge all the guns and give the castle ane new volie." James would seem throughout to have felt the greatest interest in the extraordinary new arm of artillery which had made a revolution in warfare. He pursued siege after siege with a zeal in which something of the ardour of a military enthusiast and scientific inquirer mingled with the necessities of the struggle in which he was engaged. The "Schort Cronikle," already quoted, describes him as lingering over the siege of Abercorn, "striking mony of the towers down with the gret gun, the whilk a Franche man shot richt wele, and failed na shot within a fathom where it was charged him to hit." And when, in the exultation of his heart to see each new accession of force come in, he ordered "a new volie" against the stout outstanding walls, the excitement of the discharge, the eagerness of an adept to watch the effect, no doubt made this dangerous expression of satisfaction a real demonstration of pleasure.

MONS MEG

King James had attained at this time a success which probably a few years before his warmest imagination could not have aspired to. He had brought into subjection the great families which had almost contested his throne with him. Douglas, the highest and most near himself, had been swept clean out of his way. The fiercest rebel of all, the head of the Highland caterans, with his wild host in all their savage array, was by his side, ready to charge under his orders. The country, drained of its most lawless elements, was beginning to breathe again, to sow its fields and rebuild its homesteads. Instead of the horrors of civil war his soldiers were now engaged in the most legitimate of all enterprises—the attempt to recover from England an alienated possession. Everything was bright before him, the hope of a great reign, the promise of prosperity and honour and peace.

It is almost a commonplace of human experience that in such moments the blow of fate is near at hand. The big guns which were a comparatively new wonder, full of interest in their unaccustomed operation, were still a danger as well as a prodigy, and James would seem to have forgotten the precautions that were considered necessary in presence of an armament still only partially understood. The historian assumes, as every human observer is apt to do in face of such a calamity, a tone of blame. "This Prince," says the chronicle with a shrill tone of exasperation in the record of the catastrophe, "more curious than became the majestie of a king, did stand hard by when the artilliarie was discharging." And in a moment all the labours and struggles, and the hope of the redeemed kingdom and all the prosperity that was to come, were at an end. One can imagine the sudden dismay in the group around him, the rush of his attendants, his own feeble command to keep silence when some cry of horror rose from the pale-faced circle. His thigh had been broken, "dung in two," by the explosion of the gun, "by which he was struken to the ground, and died hastilie thereafter," with no time to say more than to order silence, lest the army should be discouraged and the siege prove in vain.

So ended the troublous reign of the second James, involved in strife and warfare from his childhood, vexed by the treacheries and struggles over him of his dearest friends, full of violence alien to his mind and temper, which yet was justified by his example at the most critical moment of his life. He made his way through continual contention, intrigue, and blood, for which he was not to blame, to such a settlement of national affairs as might have consolidated Scotland and made her great—by patience and firmness and courage, and conspicuously by mercy, notwithstanding one crime. And when the helm was in his hands, and a fair future before him, fell, not ignominiously indeed, yet uselessly, a noble life thrown away, leaving once more chaos behind him. He was only twenty-nine when the thunderbolt thus falling from a clear sky destroyed all the hopes of Scotland; yet had reigned long, for twenty-three years of trouble, tumult, and distress.

CHAPTER III

JAMES III: THE MAN OF PEACE

Again the noises cease save for a wail of lamentation over the dead. The operations of war are suspended, the dark ranks of the army stand aside, and every trumpet and fatal cannon is silent while once more a woman and a child come into the foreground of the historic scene. Once more, the most pathetic figure surely in history, a little startled boy clinging to his mother—not afraid indeed of the array of war to which he has been accustomed all his life, and perhaps with an instinct in him of childish majesty, the consciousness which so soon develops even in an infant mind, of unquestioned rank, but surrounded by the atmosphere of horror and affright in which he has been taken from among his playthings—stands forth to be hastily enveloped in the robes so pitifully over-large of the dead monarch. The lords, we are told, sent for the Prince in the first sensation of the catastrophe, and had him crowned at Kelso, feeling the necessity of that central name at least, round which to rally. They were not always respectful of the real King when they had him, yet the divinity which hedged the title, however helpless the head round which it shone, was felt to be indispensable to the unity and strength of the kingdom. Mary of Gueldres in her sudden widowhood would seem to have behaved with great dignity and spirit at this critical moment. She is said to have insisted that the siege should not be abandoned, but that her husband's death might at least accomplish what his heart had been set upon; and the army after a moment of despondency was so "incouraged" by the coming of the Prince "that they forgot the death of his father and past manfullie to the hous, and wan the same, and justified the captaine theroff, and kest it down to the ground that it should not be any impediment to them hereafter." The execution of the captain seems a hard measure unless he was a traitor to the Scottish crown; but no doubt the conflict became more bitter from the terrible cost of the victory.

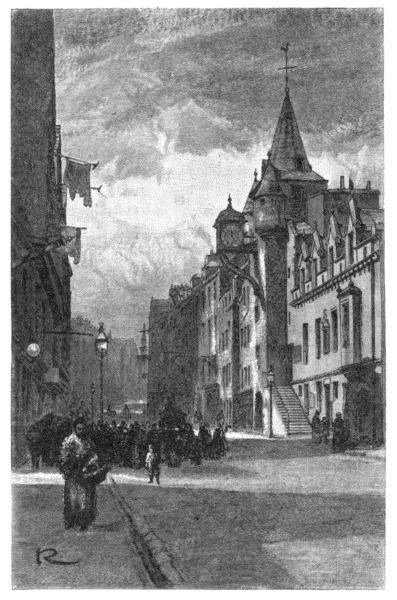

THE CANONGATE TOLBOOTH

Once more accordingly the kingdom was thrown into the chaos which in those days attended a long minority, the struggle for power, the relaxation of order, and all the evils that follow when one firm hand full of purpose drops the reins which half a dozen conflicting competitors scramble for. There was not, at first at least, anything of the foolish anarchy which drove Scotland into confusion during the childhood of James II, and opened the way to so many subsequent disasters, for Bishop Kennedy, the dead King's chief counsellor and support and a man universally trusted, was in the front of affairs, influencing if not originating all that was done: and to him, almost as a matter of course, the education of the little heir was at once confided. But Mary of Gueldres was a woman of resolution and force, and did not give up without a struggle her pretensions to the regency. Buchanan relates a scene which, according to his history, took place in Edinburgh on the occasion of the first Parliament after James's death. The Queen had established herself in the castle while Kennedy was in Holyrood, probably with his little pupil, but there is no mention made of James. On the second day of the Parliament Mary appeared suddenly in what would seem to have been, according to modern phraseology, "a packed house," her own partisans having no doubt been warned to be present by the action of some energetic "whip," and was, then and there, by a hasty Act, carried through at one sitting, appointed guardian and Regent, after which summary success she returned with great pomp to her apartments, though with what hope of having really attained a tenable position it is impossible to say. When the news was carried to Holyrood, Bishop Kennedy in his turn appeared before the Estates, which had been thus taken by surprise. It is evident that the populace of Edinburgh was excited by what had occurred—Mary's partisans no doubt rejoicing, while the people in general, always jealous of a foreigner and never very respectful of a woman, surged through the great line of street towards the castle with all the fury of a popular tumult. The High Street of Edinburgh was not unaccustomed to sudden encounters, clashing of swords between two passing lords, each with fierce followers, and all the risks of sudden brawls when neither would concede the "crown of the causeway." But the townsfolk seldom did more than look on, with perhaps an ill-concealed satisfaction in the wounds inflicted by their natural opponents upon each other. On this occasion, however, the tumult was a popular one, involving the interests of the citizens; and it is difficult to believe that the inclinations of the townsfolk would not rather lean towards the Queen, a woman of wealth and stately surroundings, likely to entertain princes and great personages and to fill Edinburgh with the splendour of a Court, than to the prelate, although his tastes also were magnificent, whose metropolis was not Edinburgh but St. Andrews, and who might consider frugality and sobriety the best qualities for the Court of a minor. At all events the crowd had risen and was ripe for tumult, when Bishop Kennedy persuaded them to pause, and reminded them of the mutual forbearance and patience and quiet which was above all necessary at such a troublous time. Other prelates would seem to have been in his train, for we are told it was the intercessions and explanations of "the bishops" which prevented the tumult from rising into a fight. The parties would seem to have been so strong, and so evenly divided, that the question was finally solved by a compromise, Parliament appointing a council of guardians, two on each side: Seaton and Boyd for the Queen; John Kennedy, brother of the Bishop, and the Earl of Orkney, for the others—an experiment which was no more successful than in the previous minority.

The Queen-mother had soon, however, something to occupy her leisure in the visit, if visit it can be called, of Henry VI and his Queen and household, fugitives before the victorious party of York, who had sought refuge from the Scots, and lodging for a thousand attendants—a request which was granted, and the convent of the Greyfriars allotted to them as their residence. The Queen at the Castle would thus be a near neighbour of the royal fugitives, and it is interesting to think of the meeting, the sympathy and mutual condolences of the two women. Margaret, the fervid Provençal, with her passionate sense of wrong and restless energy, and the hopeless task she had of maintaining and inspiring to play his part with any dignity her too patient and gentle king; and Mary, the fair and placid Fleming, stung too in her pride and affections by the refusal of the regency, and her subordination to those riotous and unmannerly lords and the proud Bishop who had got the affairs of Scotland in his hand. The two Queens might have had some previous acquaintance with each other, at a time when both had fairer hopes; at all events they amused themselves sadly, as they sat and talked together, with fancies such as please women, of making a marriage between the little Edward, the future victim of Tewkesbury, then a child at his mother's knee, and the little Princess of Scotland who played beside him, in the good days when all these troubles should be past, and Henry or his son after him should have regained the English crown. One follows with regretful interest the noble figure of Margaret, under the guise in which that sworn Lancastrian Shakspeare has disclosed it to us, before her sweeter mood had disappeared under the pressure of fate, and when not curses but hopes came from her mouth in her young motherhood, and every recovery and restoration, and happy marriage and royal state, were possible for her boy. Mary too had been cut off in the middle of her greatness. They were two Queens discrowned, two fair heads veiled with misfortune, though nothing irremediable had as yet happened, nothing that should make the future a desert though the present might be dark; ready to live again in their children, and make premature treaties over the little blonde heads at their knee. So natural a scene comes in strangely to the records of violence and misery. Nothing more tragic could be than the fate of Margaret; and the splendour and happiness had been very shortlived in Mary's experience, soon quenched in sudden destruction; but to see the two young mothers planning over the heads of the little ones how the two kingdoms were to be united, and happiness come back in a future that was never to be, while they sat together in brief companionship in those strait rooms of Edinburgh Castle, which were so narrow and so poor for a queen's habitation, or within the precincts of the Greyfriars, looking out upon the peaceful Pentlands and the soft hills of Braid, is like the recurring melody in a piece of stormy music, the bit of light in a tempestuous picture. It teaches us to perceive that, however the firmament of a kingdom may be torn with storms, there are everywhere about, even in queens' chambers, scenes of tenderness and peace.

Mary died in her own foundation of Trinity College Hospital—the beautiful church of which was demolished within living memory—three years after her husband, while her children were still very young: and thus all further struggles about the regency were ended. She does not seem indeed ever to have repeated her one stand for power. Bishop Kennedy, we may well believe, was not a man with whom there would be easy fighting. His sway procured a little respite for Scotland in the ordinary miseries of her career. The Douglases were safely out of the way and ended, and there was a truce of fifteen years with England which kept danger from that side at arm's length—not, the chroniclers assure us, from any additional love between the two countries, but because "the Inglish had warres within themselves daylie, stryvand for the crown." Kennedy lived some years after the Queen, guiding all the affairs of the kingdom so wisely that "the commounweill flourished greatly." He was a Churchman of the noblest kind, full of care for the spiritual interests of his diocese as well as for the secular affairs which were placed in his hands. "He caused all persones (parsons) and vicars to remain at their paroche kirks," says Pitscottie, "for the instruction and edifying of their flocks: and caused them preach the Word of God to the people and visit them that were sick; and also the said Bishope visited every kirk within the diocese four times in the year, and preached to the said parochin himself the Word of God, and inquired of them if they were dewly instructed by their parson and vicar, and if the poor were sustained and the youth brought up and learned according to the order that was taine in the house of God."

With all this, and many other gifts beside, among which are noted the knowledge he had of the "civil laws, having practised in the same," and his experience and sagacity in all public affairs—he was a scholar and loved all the arts. "He founded," says Pitscottie, "ane triumphant college in Sanct Androis, called Sanct Salvatore's College, wherein he made his lear (library) very curiouslie and coastlie; and also he biggit ane ship, called the Bishop's Barge, and when all three were complete, to wit, the college, the lear, and the barge, he knew not which of the three was the costliest; for it was reckoned for the time by honest men of consideration that the least of the three cost him ten thousand pound sterling." Major gives the same high character of the great Bishop, declaring that there were but two things in him which did not merit approval—the fact that he held a priory (but only one, that of Pittenweem) in commendam, "and the sumptuositie of his sepulchre." That sepulchre, half destroyed—after having remained a thing of beauty for three hundred years—by ignorant and foolish hands in the end of the eighteenth century, may still be seen in the chapel of his college at St. Andrews, the only existing memorial of the time when all Scotland was governed from that stormy headland to the great advantage of the commonwealth. It is difficult to make out from the different records whether the young King remained in the Bishop's keeping so long as he lived, which was but until James had attained the age of thirteen, or whether the usual struggle between the two sets of guardians appointed by Parliament, the Boyds and Kennedies, had begun before the Bishop's death. It may be imagined, however, that the evident advantages to the boy of Bishop Kennedy's care would outweigh any formal appointment; although at the same time the idea suggests itself whether in the perversity of human nature this training was not in itself partly the cause of James's weaknesses and errors. He would learn at St. Andrews not only what was best in the learning of the time, but as much of the arts as were known in Scotland, and especially that noble art of architecture, which has been the passion of so many princes. And no doubt he would see the advancement of professors of these arts, of men skilful and cunning in design and decoration, the builders, the sculptors, and the musicians, whose place in the great cathedral could never be unimportant. A Churchman could promote and honour such public servants in the little commonwealth of his cathedral town with greater freedom than might be done elsewhere; and James, a studious and feeble boy, not wise enough to see that the example of his great teacher was here inappropriate and out of place, learned this lesson but too well. The King grew up "a man that loved solitariness and desired never to hear of warre, but delighted more in musick and politie and building nor he did in the government of his realm." It would seem that he was also fond of money, which indeed was very necessary to the carrying out of his pursuits. It is difficult to estimate justly the position of a king of such a temperament in such circumstances, whether he is to be blamed for abandoning the national policy and tradition, or whether he was not rather conscientiously trying to carry out his stewardry of his kingdom in a better way when he withheld his countenance from the perpetual wars of the Border, and addressed himself to the construction of noble halls and chapels and the patronage of the arts. He was at least so far in advance of his time, still concerned with the rudest interests of practical life as to be universally misunderstood: and he had the further misfortune of sharing the unpopularity of the favourites with whom he surrounded himself, as almost every monarch has done who has promoted men of inferior position to the high places of the State.

James's supineness, over-refinement, and love of peaceful occupations were made the more remarkable from the contrast with two manly and chivalrous brothers, the Dukes of Mar and Albany, of fine person and energetic tastes, interested in all the operations of war, fond of fine horses and gallant doings, and coming up to all the popular expectations of what was becoming in a prince. Nothing is more difficult to make out at any time than the real motives and meaning of family discords: and this is still more the case in an age not yet enlightened by the clear light of history. The chroniclers, especially Boece, have much doubt thrown upon them by more serious historians, who quote them and build upon them nevertheless, having really no better evidence to go upon. The report of these witnesses is that James had been warned by witches, in whom he believed, and by one Andrew the Fleming, an astrologer, that his chief danger arose from his own family, and that "the lion should be devoured by his whelps." Pitscottie's account, however, indicates a conspiracy between Cochrane and the Homes, whom Albany had mortally offended, as the cause at once of these prophecies and the King's alarm. The only thing clear is that he was afraid of his brothers, and considered their existence a danger to his life. It would appear that he had already begun to surround himself with those favourites to whom was attributed every evil thing in his reign, when this poison was first instilled into his mind: and the blame was attributed rightly or wrongly to Cochrane, the chief of his "minions," who very probably felt it to be to his interest to detach from James's side the manly and gallant brothers who were naturally his nearest counsellors and champions.

There is very little that is authentic known of the men whom James III thus elevated to the steps of his throne. Cochrane was an architect probably, though called a mason in his earlier career, and had no doubt been employed on some of the buildings in which the King delighted, being "verrie ingenious" and "cunning in that craft." Perhaps, however, to make the royal favour for a mere craftsman more respectable, according to the notions of the time, it is added in a popular story that the favourite was a man of great strength and stature, whose prowess in some brawl attracted the admiration of the timid monarch, to whom a man who was a tall fellow of his hands, as well as a person of similar tastes to himself, might well be a special object of approval. A musician, William Roger, an Englishman, whose voice had charmed the King—a weakness which at least was not ignoble, and was shared by various other members of his race—was the second of James's favourites: and there were others still less important—one the King's tailor—a band of persons of no condition, who surrounded him no doubt with flattery and adulation, since their promotion and maintenance were entirely dependent on his pleasure. King Louis XI was at that time upon the throne of France, a powerful prince whose little privy council was composed of equally mean men, and perhaps some reflection from the Court of the old ally of Scotland made young James believe that this was the best and wisest thing for a King to do. Louis was also a believer in astrologers, witches, and all the prophecies and omens in which they dealt. To copy him was not a high ambition, but he was in his way a great king, and it is conceivable that the feeble monarch of Scotland, never roused to the height of his father's or grandfather's example, took a little satisfaction in copying what he could from Louis. The example of Oliver le Dain might make him think that he showed his superiority by preferring his tailor, a man devoted to his service, to Albany or Angus. And if Louis trembled at the predictions of his Eastern sage, what more natural than that James should quake when the stars revealed a danger which every spaewife confirmed? No doubt he would know well the story of the mysterious spaewife who, had her advice been taken, might have saved James I. from his murderers. It is rarely that there is not a certain cruelty involved in selfish cowardice. In a sudden panic the mildest-seeming creature will trample down furiously any weaker being who stands in the way of his own safety, and James was ready for any atrocity when he was convinced that his brothers were a danger to his life and crown. The youngest, the handsome and gallant Mar, was killed by one treachery or another; and Alexander of Albany, the inheritor of that ill-omened title, was laid up in prison to be safe out of his brother's way.