Полная версия

Полная версияMiss Marjoribanks

Lucilla, however, in her own person took no part in it at all, one way or other. She shook hands very kindly with Barbara, and hoped she would come and see her, and made it clearly apparent that she at least bore no malice. "I am very glad I told Thomas to say nothing about it," she said to Aunt Jemima, who, however, did not know the circumstances, and was very little the wiser, as may be supposed.

And then the two ladies walked home together, and Miss Marjoribanks devoted herself to her good books. It was almost the first moment of repose that Lucilla had ever had in her busy life, and it was a repose not only permitted but enjoined. Society, which had all along expected so much from her, expected now that she should not find herself able for any exertion; and Miss Marjoribanks responded nobly, as she had always done, to the requirements of society. To a mind less perfectly regulated, the fact that the election which had been so interesting to her was now about, as may be said, to take place without her, would have been of itself a severe trial; and the sweet composure with which she bore it was not one of the least remarkable phenomena of the present crisis. But the fact was that this Sunday was on the whole an oppressive day. Mr Ashburton came in for a moment, it is true, between services; but he himself, though generally so steady, was unsettled and agitated. He had been bearing the excitement well until this last almost incredible accident occurred, which made it possible that he might not only win, but win by a large majority. "The Dissenters have all held out till now, and would not pledge themselves," he said to Lucilla, actually with a tremble in his voice; and then he told her about Mr Tufton's sermon and the wickedness in high places, and the hand imbrued metaphorically in his sister's blood.

"I wonder how he could say so," said Lucilla, with indignation. "It is just like those Dissenters. What harm was there in going to see her? I heard of it last night, but even for your interest I would never have spread such mere gossip as that."

"No – certainly it is mere gossip," said Mr Ashburton; "but it will do him a great deal of harm all the same," and then once more he got restless and abstracted. "I suppose it is of no use asking you if you would join Lady Richmond's party at the Blue Boar? You could have a window almost to yourself, you know, and would be quite quiet."

Lucilla shook her head, and the movement was more expressive than words. "I did not think you would," said Mr Ashburton; and then he took her hand, and his looks too became full of meaning. "Then I must say adieu," he said – "adieu until it is all over. I shall not have a moment that I can call my own – this will be an eventful week for me."

"You mean an eventful day," said Lucilla; for Mr Ashburton was not such a novice as to be afraid of the appearance he would have to make at the nomination. He did not contradict her, but he pressed her hand with a look which was equivalent to kissing it, though he was not romantic enough to go quite that length. When he was gone, Miss Marjoribanks could not but wonder a little what he could mean by looking forward to an eventful week. For her own part, she could not but feel that after so much excitement things would feel rather flat for the rest of the week, and that it was almost wrong to have an election on a Tuesday. Could it be that Mr Ashburton had some other contest or candidateship in store for himself which he had not told her about? Such a thing was quite possible; but what had Lucilla in her mourning to do with worldly contingencies? She went back to her seat in the corner of the sofa and her book of sermons, and read fifty pages before tea-time; she knew how much, because she had put a mark in her book when Mr Ashburton came in. Marks are very necessary things generally in sermon-books; and Lucilla could not but feel pleased to think that since her visitor went away she had got over so much ground.

To compare Carlingford to a volcano that night (and indeed all the next day, which was the day of nomination) would be a stale similitude; and yet in some respects it was like a volcano. It was not the same kind of excitement which arises in a town where politics run very high – if there are any towns nowadays in such a state of unsophisticated nature. Neither was it a place where simple corruption could carry the day; for the freemen of Wharfside were, after all, but a small portion of the population. It was in reality a quite ideal sort of contest – a contest for the best man, such as would have pleased the purest-minded philosopher. It was the man most fit to represent Carlingford for whom everybody was looking, not a man to be baited about parish-rates and Reform Bills and the Irish Church; – a man who lived in, or near the town, and "dealt regular" at all the best shops; a man who would not disgrace his constituency by any unlawful or injudicious sort of love-making – who would attend to the town's interests and subscribe to its charities, and take the lead in a general way. This was what Carlingford was looking for, as Miss Marjoribanks, with that intuitive rapidity which was characteristic of her genius, had at once remarked; and when everybody went home from church and chapel, though it was Sunday, the whole town thrilled and throbbed with this great question. People might have found it possible to condone a sin or wink at a mere backsliding; but there were few so bigoted in their faith as to believe that the man who was capable of marrying Barbara Lake could ever be the man for Carlingford; and thus it was that Mr Cavendish, who had been flourishing like a green bay-tree, withered away, as it were, in a moment, and the place that had known him knew him no more.

The hustings were erected at that central spot, just under the windows of the Blue Boar, where Grange Lane and George Street meet, the most central point in Carlingford. It was so near that Lucilla could hear the shouts and the music and all the divers noises of the election, but could not, even when she went into the very corner of the window and strained her eyes to the utmost, see what was going on, which was a very trying position. We will not linger upon the proceedings or excitement of Monday, when the nomination and the speeches were made, and when the show of hands was certainly thought to be in Mr Cavendish's favour. But it was the next day that was the real trial. Lady Richmond and her party drove past at a very early hour, and looked up at Miss Marjoribanks's windows, and congratulated themselves that they were so early, and that poor dear Lucilla would not have the additional pain of seeing them go past. But Lucilla did see them, though, with her usual good sense, she kept behind the blind. She never did anything absurd in the way of early rising on ordinary occasions; but this morning it was impossible to restrain a certain excitement, and though it did her no good, still she got up an hour earlier than usual, and listened to the music, and heard the cabs rattling about, and could not help it if her heart beat quicker. It was perhaps a more important crisis for Miss Marjoribanks than for any other person, save one, in Carlingford; for of course it would be foolish to attempt to assert that she did not understand by this time what Mr Ashburton meant; and it may be imagined how hard it was upon Lucilla to be thus, as it were, in the very outside row of the assembly – to hear all the distant shouts and sounds, everything that was noisy and inarticulate, and conveyed no meaning, and to be out of reach of all that could really inform her as to what was going on.

She saw from her window the cabs rushing past, now with her own violet-and-green colours, now with the blue-and-yellow. And sometimes it seemed to Lucilla that the blue-and-yellow predominated, and that the carriages which mounted the hostile standard carried voters in larger numbers and more enthusiastic condition. The first load of bargemen that came up Grange Lane from the farther end of Wharf side were all Blues; and when a spectator is thus held on the very edge of the event in a suspense which grows every moment more intolerable, especially when he or she is disposed to believe that things in general go on all the worse for his or her absence, it is no wonder if that spectator becomes nervous, and sees all the dangers at their darkest. What if, after all, old liking and friendship had prevailed over that beautiful optimism which Lucilla had done so much to instil into the minds of her townsfolk? What if something more mercenary and less elevating than the ideal search for the best man, in which she had hoped Carlingford was engaged, should have swayed the popular mind to the other side? All these painful questions went through Lucilla's mind as the day crept on; and her suspense was much aggravated by Aunt Jemima, who took no real interest in the election, but who kept saying every ten minutes – "I wonder how the poll is going on – I wonder what that is they are shouting – is it 'Ashburton for ever!' or 'Cavendish for ever!' Lucilla? Your ears should be sharper than mine; but I think it is Cavendish." Lucilla thought so too, and her heart quaked within her, and she went and squeezed herself into the corner of the window, to try whether it was not possible to catch a glimpse of the field of battle; and her perseverance was finally rewarded by the sight of the extremity of the wooden planks which formed the polling-booth; but there was little satisfaction to be got out of that. And then the continual dropping of Aunt Jemima's questions drove her wild. "My dear aunt," she said at last, "I can see nothing and hear nothing, and you know as much about what is going on as I do" – which, it will be acknowledged, was not an answer such as one would have expected from Lucilla's perfect temper and wonderful self-control.

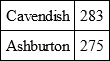

The election went on with all its usual commotion while Miss Marjoribanks watched and waited. Mr Cavendish's committee brought their supporters very well up in the morning – no doubt by way of making sure of them, as somebody suggested on the other side; and for some time Mrs Woodburn's party at Masters's windows (which Masters had given rather reluctantly, by way of pleasing the Rector) looked in better spirits and less anxious than Lady Richmond's party, which was at the Blue Boar. Towards noon Mr Cavendish himself went up to his female supporters with the bulletin of the poll – the same bulletin which Mr Ashburton had just sent down to Lucilla. These were the numbers; and they made Masters's triumphant, while silence and anxiety fell upon the Blue Boar: —

When Miss Marjoribanks received this disastrous intelligence, she put the note in her pocket without saying a word to Aunt Jemima, and left her window, and went back to her worsted-work; but as for Mrs Woodburn, she gave her brother a hug, and laughed, and cried, and believed in it, like a silly woman as she was.

"It is something quite unlooked-for, and which I never could have calculated upon," she said, thrusting her hand into an imaginary waistcoat with Mr Ashburton's very look and tone, which was beyond measure amusing to all the party. They laughed so long, and were so gay, that Lady Richmond solemnly levelled her opera-glass at them with the air of a woman who was used to elections, but knew how such parvenus have their heads turned by a prominent position. "That woman is taking some of us off," she said, "but if it is me, I can bear it. There is nothing so vulgar as that sort of thing, and I hope you never encourage it in your presence, my dears."

Just at that moment, however, an incident occurred which took up the attention of the ladies at the windows, and eclipsed even the interest of the election. Poor Barbara Lake was interested, too, to know if her friend would win. She was not entertaining any particular hopes or plans about him. Years and hard experiences had humbled Barbara. The Brussels veil which she used to dream of had faded as much from her memory as poor Rose's Honiton design, for which she had got the prize. At the present moment, instead of nourishing the ambitious designs which everybody laid to her charge, she would have been content with the very innocent privilege of talking a little to her next employers about Mr Cavendish, the member for Carlingford, and his visits to her father's house. But at the same time, she had once been fond of him, and she took a great interest in him, and was very anxious that he should win. And she was in the habit, like so many other women, of finding out, as far as she could, what was going on, and going to see everything that there might be to see. She had brought one of her young brothers with her, whose anxiety to see the fun was quite as great as her own; and she was arrayed in the tin dress – her best available garment – which was made long, according to the fashion, and which, as Barbara scorned to tuck it up, was continually getting trodden on, and talked about, and reviled at, on that crowded pavement. The two parties of ladies saw, and even it might be said heard, the sweep of the metallic garment, which was undergoing such rough usage, and which was her best, poor soul. Lady Richmond had alighted from her carriage carefully tucked up, though there were only a few steps to make, and there was no lady in Carlingford who would have swept "a good gown" over the stones in such a way; but then poor Barbara was not precisely a lady, and thought it right to look as if it did not matter. She went up to read the numbers of the poll – in the sight of everybody; and she clasped her hands together with ecstatic satisfaction as she read; and young Carmine, her brother, dashed into the midst of the fray, and shouted "Cavendish for ever! hurrah for Cavendish!" and could scarcely be drawn back again to take his sister home. Even when she withdrew, she did not go home, but went slowly up and down Grange Lane with her rustling train behind her, with the intention of coming back for further information. Lady Richmond and Mrs Woodburn both lost all thought of the election as they watched; and lo! when their wandering thoughts came back again, the tide had turned.

The tide had turned. Whether it was Barbara, or whether it was fate, or whether it was the deadly unanimity of those Dissenters, who, after all their wavering, had at last decided for the man who "dealt" in George Street – no one could tell; but by two o'clock Mr Ashburton was so far ahead that he felt himself justified in sending another bulletin to Lucilla – so far that there was no reasonable hope of the opposite candidate ever making up his lost ground. Mrs Woodburn was not a woman to be content when reasonable hope was over – she clung to the last possibility desperately, with a pertinacity beyond all reason, and swore in her heart that it was Barbara that had done it, and cursed her with her best energies; which, however, as these are not melodramatic days, was a thing which did the culprit no possible harm. When Barbara herself came back from her promenade in Grange Lane, and saw the altered numbers, she again clasped her hands together for a moment, and looked as if she were going to faint; and it was at that moment that Mr Cavendish's eyes fell upon her, as ill fortune would have it. They were all looking at him as if it was his fault; and the sight of that sympathetic face was consoling to the defeated candidate. He took off his hat before everybody; probably, as his sister afterwards said, he would have gone and offered her his arm had he been near enough. How could anybody wonder, after that, that things had gone against him, and that, notwithstanding all his advantages, he was the loser in the fight?

As for Lucilla, she had gone back to her worsted-work when she got Mr Ashburton's first note, in which his rival's name stood above his own. She looked quite composed, and Aunt Jemima went on teasing with her senseless questions. But Miss Marjoribanks put up with it all; though the lingering progress of these hours from one o'clock to four, the sound of cabs furiously driven by, the distant shouts, the hum of indefinite din that filled the air, exciting every moment a keener curiosity, and giving no satisfaction or information, would have been enough to have driven a less large intelligence out of its wits. Lucilla bore it, doing as much as she could of her worsted-work, and saying nothing to nobody, except, indeed, an occasional word to Aunt Jemima, who would have an answer. She was not walking about Grange Lane repeating a kind of prayer for the success of her candidate, as Barbara Lake was doing; but perhaps, on the whole, Barbara had the easiest time of it at that moment of uncertainty. When the next report came, Lucilla's fingers trembled as she opened it, so great was her emotion; but after that she recovered herself as if by magic. She grew pale, and then gave a kind of sob, and then a kind of laugh, and finally put her worsted-work back into her basket, and threw Mr Ashburton's note into the fire.

"It is all right," said Lucilla. "Mr Ashburton is a hundred ahead, and they can never make up that. I am so sorry for poor Mr Cavendish. If he only had not been so imprudent on Saturday night!"

"I am sure I don't understand you," said Aunt Jemima. "After being so anxious about one candidate, how can you be so sorry for the other? I suppose you did not want them both to win?"

"Yes, I think that was what I wanted," said Lucilla, drying her eyes; and then she awoke to the practical exigencies of the position. "There will be quantities of people coming to have a cup of tea, and I must speak to Nancy," she said, and went downstairs with a cheerful heart. It might be said to be as good as decided, so far as regarded Mr Ashburton; and when it came for her final judgment, what was it that she ought to say?

It was very well that Miss Marjoribanks's unfailing foresight led her to speak to Nancy; for the fact was, that after four o'clock, when the polling was over, everybody came in to tea. All Lady Richmond's party came, as a matter of course, and Mr Ashburton himself, for a few minutes, bearing meekly his new honours; and so many more people besides, that but for knowing it was a special occasion, and that "our gentleman" was elected, Nancy's mind never could have borne the strain. And the tea that was used was something frightful. As for Aunt Jemima, who had just then a good many thoughts of her own to occupy her, and did not care so much as the rest for all the chatter that was going on, nor for all those details about poor Barbara and Mr Cavendish's looks, which Lucilla received with such interest, she could not but make a calculation in passing as to this new item of fashionable expenditure into which her niece was plunging so wildly. To be sure, it was an occasion that never might occur again, and everybody was so excited as to forget even that Lucilla was in mourning, and that such a number of people in the house so soon might be more than she could bear. And she was excited herself, and forgot that she was not able for it. But still Aunt Jemima, sitting by, could not help thinking, that even five-o'clock teas of good quality and unlimited amount would very soon prove to be impracticable upon two hundred a year.

Chapter XLIX

Mr Ashburton, it may be supposed, had but little time to think on that eventful evening; and yet he was thinking all the way home, as he drove back in the chilly spring night to his own house. If his further course of action had been made in any way to depend upon the events of this day, it was now settled beyond all further uncertainty; and though he was not a man in his first youth, nor a likely subject for a romantic passion, still he was a little excited by the position in which he found himself. Miss Marjoribanks had been his inspiring genius, and had interested herself in his success in the warmest and fullest way; and if ever a woman was made for a certain position, Lucilla was made to be the wife of the Member for Carlingford. Long, long ago, at the very beginning of her career, when it was of Mr Cavendish that everybody was thinking, the ideal fitness of this position had struck everybody. Circumstances had changed since then, and Mr Cavendish had fallen, and a worthier hero had been placed in his stead; but though the person was changed, the circumstances remained unaltered. Natural fitness was indeed so apparent, that many people would have been disposed to say that it was Lucilla's duty to accept Mr Ashburton, even independent of the fact that he was perfectly eligible in every other respect.

But with all this the new Member for Carlingford was not able to assure himself that there had been anything particular in Lucilla's manner to himself. With her as with Carlingford, it was pure optimism. He was the best man, and her quick intelligence had divined it sooner than anybody else had done. Whether there was anything more in it, Mr Ashburton could not tell. His own impression was that she would accept him; but if she did not, he would have no right to complain of "encouragement," or to think himself jilted. This was what he was thinking as he drove home; but at the same time he was very far from being in a desponding state of mind. He felt very nearly as sure that Lucilla would be his wife, as if they were already standing before the Rector in Carlingford Church. He had just won one victory, which naturally made him feel more confident of winning another; and even without entertaining any over-exalted opinion of himself, it was evident that, under all the circumstances, a woman of thirty, with two hundred a year, would be a fool to reject such an offer. And Lucilla was the very furthest in the world from being a fool. It was in every respect the beginning of a new world to Mr Ashburton, and it would have been out of nature had he not been a little excited. After the quiet life he had led at the Firs, biding his time, he had now to look forward to a busy and important existence, half of it spent amid the commotion and ceaseless stir of town. A new career, a wife, a new position, the most important in his district – it was not much wonder if Mr Ashburton felt a little excited. He was fatigued at the same time, too much fatigued to be disposed for sleep; and all these united influences swayed him to a state of mind very much unlike his ordinary sensible calm. All his excitement culminated so in thoughts of Lucilla, that the new Member felt himself truly a lover; and late as the hour was, he took up a candle and once more made a survey all alone of his solitary house.

Nothing could look more dismal than the dark rooms, where there was neither light nor fire – the great desert drawing-room, for example, which stood unchanged as it had been in the days of his grand-aunts, the good old ladies who had bequeathed the Firs to Mr Ashburton. He had made no change in it, and scarcely ever used it, keeping to his library and dining-room, with the possibility, no doubt, always before him of preparing it in due course of time for his wife. That moment had now arrived, and in his excitement he went into the desolate room with his candle, which just made the darkness visible, and tried to see the dusky curtains and faded carpet, and the indescribable fossil air which everything had. There were the odd little spider-legged stands, upon which the Miss Penrhyns had placed their work-boxes, and the old sofas on which they had sat, and the floods of old tapestry-work with which they had decorated their favourite sitting-room. The sight of it chilled the Member for Carlingford, and made him sad. He tried to turn his thoughts to the time when this same room should be fitted up to suit Lucilla's complexion, and should be gay with light and with her presence. He did all he could to realise the moment when, with a mistress so active and energetic, the whole place would change its aspect, and glow forth resplendent into the twilight of the county, a central point for all. Perhaps it was his fatigue which gained upon him just at this moment, and repulsed all livelier thoughts; but the fact is, that however willing Lucilla might turn out to be, her image was coy, and would not come. The more Mr Ashburton tried to think of her as in possession here, the more the grim images of the two old Miss Penrhyns walked out of the darkness and asserted their prior claims. They even seemed to have got into the library before him when he went back, though there his fire was burning, and his lamp. After that there was nothing left for a man to do, even though he had been that day elected Member for Carlingford, but to yield to the weakness of an ordinary mortal, and go to bed.