Полная версия

Полная версияRemarks

You will understand, gentlemen, the delicate nature of this request, I trust, and not misconstrue my motives. My intentions are perfectly honorable, and my idea in doing this is, I may say, to supply a long felt want.

Hoping that what I have said will meet with your approval and hearty cooperation, and that our very friendly business relations, as they have existed in the past, may continue through the years to come, and that your bank may wallow in success till the cows come home, or words to that effect, I beg leave to subscribe myself, yours in favor of one country, one flag and one bank account.

A Resign

Postoffice Divan, Laramie City, W.T., Oct. 1, 1883.

To the President of the United States:

Sir.—I beg leave at this time to officially tender my resignation as postmaster at this place, and in due form to deliver the great seal and the key to the front door of the office. The safe combination is set on the numbers 33, 66 and 99, though I do not remember at this moment which comes first, or how many times you revolve the knob, or which direction you should turn it at first in order to make it operate.

There is some mining stock in my private drawer in the safe, which I have not yet removed. This stock you may have, if you desire it. It is a luxury, but you may have it. I have decided to keep a horse instead of this mining stock. The horse may not be so pretty, but it will cost less to keep him.

You will find the postal cards that have not been used under the distributing table, and the coal down in the cellar. If the stove draws too hard, close the damper in the pipe and shut the general delivery window.

Looking over my stormy and eventful administration as postmaster here, I find abundant cause for thanksgiving. At the time I entered upon the duties of my office the department was not yet on a paying basis. It was not even self-sustaining. Since that time, with the active co-operation of the chief executive and the heads of the department, I have been able to make our postal system a paying one, and on top of that I am now able to reduce the tariff on average-sized letters from three cents to two. I might add that this is rather too too, but I will not say anything that might seem undignified in an official resignation which is to become a matter of history.

Through all the vicissitudes of a tempestuous term of office I have safely passed. I am able to turn over the office to-day in a highly improved condition, and to present a purified and renovated institution to my successor.

Acting under the advice of Gen. Hatton, a year ago, I removed the feather bed with which my predecessor, Deacon Hayford, had bolstered up his administration by stuffing the window, and substituted glass. Finding nothing in the book of instructions to postmasters which made the feather bed a part of my official duties, I filed it away in an obscure place and burned it in effigy, also in the gloaming. This act maddened my predecessor to such a degree, that he then and there became a candidate for justice of the peace on the Democratic ticket. The Democratic party was able, however, with what aid it secured from the Republicans, to plow the old man under to a great degree.

It was not long after I had taken my official oath before an era of unexampled prosperity opened for the American people. The price of beef rose to a remarkable altitude, and other vegetables commanded a good figure and a ready market. We then began to make active preparations for the introduction of the strawberry-roan two-cent stamps and the black-and-tan postal note. One reform has crowded upon the heels of another, until the country is to-day upon the foam-crested wave of permanent prosperity.

Mr. President, I cannot close this letter without thanking yourself and the heads of departments at Washington for your active, cheery and prompt cooperation in these matters. You can do as you see fit, of course, about incorporating this idea into your Thanksgiving proclamation, but rest assured it would not be ill-timed or inopportune. It is not alone a credit to myself, It reflects credit upon the administration also.

I need not say that I herewith transmit my resignation with great sorrow and genuine regret. We have toiled on together month after month, asking for no reward except the innate consciousness of rectitude and the salary as fixed by law. Now we are to separate. Here the roads seem to fork, as it were, and you and I, and the cabinet, must leave each other at this point.

You will find the key under the door-mat, and you had better turn the cat out at night when you close the office. If she does not go readily, you can make it clearer to her mind by throwing the cancelling stamp at her.

If Deacon Hayford does not pay up his box-rent, you might as well put his mail in the general delivery, and when Bob Head gets drunk and insists on a letter from one of his wives every day in the week, you can salute him through the box delivery with an old Queen Anne tomahawk, which you will find near the Etruscan water-pail. This will not in any manner surprise either of these parties.

Tears are unavailing. I once more become a private citizen, clothed only with the right to read such postal cards as may be addressed to me personally, and to curse the inefficiency of the postoffice department. I believe the voting class to be divided into two parties, viz: Those who are in the postal service, and those who are mad because they cannot receive a registered letter every fifteen minutes of each day, including Sunday.

Mr. President, as an official of this Government I now retire. My term of office would not expire until 1886. I must, therefore, beg pardon for my eccentricity in resigning. It will be best, perhaps, to keep the heart-breaking news from the ears of European powers until the dangers of a financial panic are fully past. Then hurl it broadcast with a sickening thud.

My Mine

I have decided to sacrifice another valuable piece of mining property this spring. It would not be sold if I had the necessary capital to develop it. It is a good mine, for I located it myself. I remember well the day I climbed up on the ridge-pole of the universe and nailed my location notice to the eaves of the sky.

It was in August that I discovered the Vanderbilt claim in a snow-storm. It cropped out apparently a little southeast of a point where the arc of the orbit of Venus bisects the milky way, and ran due east eighty chains, three links and a swivel, thence south fifteen paces and a half to a blue spot in the sky, thence proceeding west eighty chains, three links of sausage and a half to a fixed star, thence north across the lead to place of beginning.

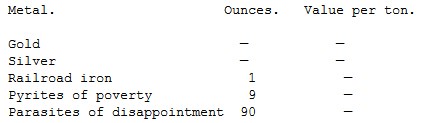

The Vanderbilt set out to be a carbonate deposit, but changed its mind. I sent a piece of the cropping to a man over in Salt Lake, who is a good assayer and quite a scientist, if he would brace up and avoid humor. His assay read as follows to-wit:

Salt Lake City, U.T., August 25, 1877.

Mr. Bill Nye:—Your specimen of ore No. 35832, current series, has been submitted to assay and shows the following result:

McVicker, Assayer.

Note.—I also find that the formation is igneous, prehistoric and erroneous. If I were you I would sink a prospect shaft below the vertical slide where the old red brimstone and preadamite slag cross-cut the malachite and intersect the schist. I think that would be schist about as good as anything you could do. Then send me specimens with $2 for assay and we shall see what we shall see.

Well, I didn’t know he was “an humorist,” you see, so I went to work on the Vanderbilt to try and do what Mac. said. I sank a shaft and everything else I could get hold of on that claim. It was so high that we had to carry water up there to drink when we began and before fall we had struck a vein of the richest water you ever saw. We had more water in that mine than the regular army could use.

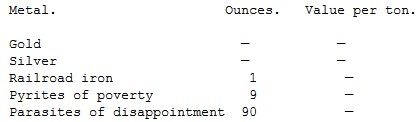

When we got down sixty feet I sent some pieces of the pay streak to the assayer again. This time he wrote me quite a letter, and at the same time inclosed the certificate of assay.

Salt Lake City, U.T., October 3, 1877.

Mr. Bill Nye:—Your specimen of ore No. 36132, current series, has been submitted to assay and shows the following result:

McVicker, Assayer.

In the letter he said there was, no doubt, something in the claim if I could get the true contact with calcimine walls denoting a true fissure. He thought I ought to run a drift. I told him I had already run adrift.

Then he said to stope out my stove polish ore and sell it for enough to go on with the development. I tried that, but capital seemed coy. Others had been there before me and capital bade me soak my head and said other things which grated harshly on my sensitive nature.

The Vanderbilt mine, with all its dips, spurs, angles, variations, veins, sinuosities, rights, titles, franchises, prerogatives and assessments is now for sale. I sell it in order to raise the necessary funds for the development of the Governor of North Carolina. I had so much trouble with water in the Vanderbilt, that I named the new claim the Governor of North Carolina, because he was always dry.

Mush and Melody

Lately I have been giving a good deal of attention to hygiene—in other people. The gentle reader will notice that, as a rule, the man who gives the most time and thought to this subject is an invalid himself; just as the young theological student devotes his first sermon to the care of children, and the ward politician talks the smoothest on the subject of how and when to plant ruta-bagas or wean a calf from the parent stem.

Having been thrown into the society of physicians a great deal the past two years, mostly in the role of patient, I have given some study to the human form; its structure and idiosyncracies, as it were. Perhaps few men in the same length of time have successfully acquired a larger or more select repertoire of choice diseases than I have. I do not say this boastfully. I simply desire to call the attention of our growing youth to the glorious possibilities that await the ambitious and enterprising in this line.

Starting out as a poor boy, with few advantages in the way of disease, I have resolutely carved my way up to the dizzy heights of fame as a chronic invalid and drug-soaked relic of other days. I inherited no disease whatever. My ancestors were poor and healthy. They bequeathed me no snug little nucleus of fashionable malaria such as other boys had. I was obliged to acquire it myself. Yet I was not discouraged. The results have shown that disease is not alone the heritage of the wealthy and the great. The poorest of us may become eminent invalids if we will only go at it in the right way. But I started out to say something on the subject of health, for there are still many common people who would rather be healthy and unknown than obtain distinction with some dazzling new disease.

Noticing many years ago that imperfect mastication and dyspepsia walked hand in hand, so to speak, Mr. Gladstone adopted in his family a regular mastication scale; for instance, thirty-two bites for steak, twenty-two for fish, and so forth. Now I take this idea and improve upon it. Two statesmen can always act better in concert if they will do so.

With Mr. Gladstone’s knowledge of the laws of health and my own musical genius, I have hit on a way to make eating not only a duty, but a pleasure. Eating is too frequently irksome. There is nothing about it to make it attractive.

What we need is a union of mush and melody, if I may be allowed that expression. Mr. Gladstone has given us the graduated scale, so that we know just what metre a bill of fare goes in as quick as we look at it. In this way the day is not far distant when music and mastication will march down through the dim vista of years together.

The Baked Bean Chant, the Vermicelli Waltz, the Mush and Milk March, the sad and touchful Pumpkin Pie Refrain, the gay and rollicking Oxtail Soup Gallop, and the melting Ice Cream Serenade will yet be common musical names.

Taking different classes of food, I have set them to music in such a way that the meal, for instance, may open with a Soup Overture, to be followed by a Roast Beef March in C, and so on, closing with a kind of Mince Pie La Somnambula pianissimo in G. Space, of course, forbids an extended description of this idea as I propose to carry it out, but the conception is certainly grand. Let us picture the jaws of a whole family moving in exact time to a Strauss waltz on the silent remains of the late lamented hen, and we see at once how much real pleasure may be added to the process of mastication.

The Blase Young Man

I have just formed the acquaintance of a blase young man. I have been on an extended trip with him. He is about twenty-two years old, but he is already weary of life. He was very careful all the time never to be exuberant. No matter how beautiful the landscape, he never allowed himself to exube.

Several times I succeeded in startling him enough to say “Ah!” but that was all. He had the air all the time of a man who had been reared in luxury and fondled so much in the lap of wealth that he was weary of life, and yearned for a bright immortality. I have often wished that the pruning-hook of time would use a little more discretion. The blase young man seemed to be tired all the time. He was weary of life because life was hollow.

He seemed to hanker for the cool and quiet grave. I wished at times that the hankering might have been more mutual. But what does a cool, quiet grave want of a young man who never did anything but breathe the nice pure air into his froggy lungs and spoil it for everybody else?

This young man had a large grip-sack with him which he frequently consulted. I glanced into it once while he left it open. It was not right, but I did it. I saw the following articles in it:

31 Assorted Neckties.

1 pair Socks (whole).

1 pair do. (not so whole).

17 Collars.

1 Shirt

1 quart Cuff-Buttons.

1 suit discouraged Gauze Underwear.

1 box Speckled Handkerchiefs.

1 box Condition Powders.

1 Toothbrush (prematurely bald).

1 copy Martin F. Tupper’s Works.

1 box Prepared Chalk.

1 Pair Tweezers for encouraging Moustache to come out to breakfast.

1 Powder Rag.

1 Gob ecru-colored Taffy.

1 Hair-brush, with Ginger Hair in it.

1 Pencil to pencil Moustache at night.

1 Bread and Milk Poultice to put on Moustache on retiring, so that it will

not forget to come out again the next day.

1 Box Trix for the breath.

1 Box Chloride of Lime to use in case breath becomes unmanageable.

1 Ear-spoon (large size).

1 Plain Mourning Head for Cane.

1 Vulcanized Rubber Head for Cane (to bite on).

1 Shoe-horn to use in working Ears into Ear-Muffs.

1 Pair Corsets.

1 Dark-brown Wash for Mouth, to be used in the morning.

1 Large Box Ennui, to be used in Society.

1 Box Spruce Gum, made in Chicago and warranted pure.

1 Gallon Assorted Shirt Studs.

1 Polka-dot Handkerchief to pin in side pocket, but not for nose.

1 Plain Handkerchief for nose.

1 Fancy Head for Cane (morning).

1 Fancy Head for Cane (evening).

1 Picnic Head for Cane.

1 Bottle Peppermint.

1 do. Catnip.

1 Waterbury Watch.

7 Chains for same.

1 Box Letter Paper.

1 Stick Sealing Wax (baby blue).

1 do “ (Bismarck brindle).

1 do “ (mashed gooseberry).

1 Seal for same.

1 Family Crest (wash-tub rampant on a field calico).

There were other little articles of virtu and bric-a-brac till you couldn’t rest, but these were all that I could see thoroughly before he returned from the wash-room.

I do not like the blase young man as a traveling companion. He is nix bonum. He is too E pluribus for me. He is not de trop or sciatica enough to suit my style.

If he belonged to me I would picket him out somewhere in a hostile Indian country, and then try to nerve myself up for the result.

It is better to go through life reading the signs on the ten-story buildings and acquiring knowledge, than to dawdle and “Ah!” adown our pathway to the tomb and leave no record for posterity except that we had a good neck to pin a necktie upon. It is not pleasant to be called green, but I would rather be green and aspiring than blase and hide-bound at nineteen.

Let us so live that when at last we pass away our friends will not be immediately and uproariously reconciled to our death.

History of Babylon

The history of Babylon is fraught with sadness. It illustrates, only too painfully, that the people of a town make or mar its success rather than the natural resources and advantages it may possess on the start.

Thus Babylon, with 3,000 years the start of Minneapolis, is to-day a hole in the ground, while Minneapolis socks her XXXX flour into every corner of the globe, and the price of real estate would make a common dynasty totter on its throne.

Babylon is a good illustration of the decay of a town that does not keep up with the procession. Compare her to-day with Kansas City. While Babylon was the capital of Chaldea, 1,270 years before the birth of Christ, and Kansas City was organized so many years after that event that many of the people there have forgotten all about it, Kansas City has doubled her population in ten years, while Babylon is simply a gothic hole in the ground.

Why did trade and emigration turn their backs upon Babylon and seek out Minneapolis, St. Paul, Kansas City and Omaha? Was it because they were blest with a bluer sky or a more genial sun? Not by any means. While Babylon lived upon what she had been and neglected to advertise, other towns with no history extending back into the mouldy past, whooped with an exceeding great whoop and tore up the ground and shed printers’ ink and showed marked signs of vitality. That is the reason that Babylon is no more.

This life of ours is one of intense activity. We cannot rest long in idleness without inviting forgetfulness, death and oblivion. “Babylon was probably the largest and most magnificent city of the ancient world.” Isaiah, who lived about 300 years before Herodotus, and whose remarks are unusually free from local or political prejudice, refers to Babylon as “the glory of kingdoms, the beauty of the Chaldic’s excellency,” and, yet, while Cheyenne has the electric light and two daily papers, Babylon hasn’t got so much as a skating rink.

A city fourteen miles square with a brick wall around it 355 feet high, she has quietly forgotten to advertise, and in turn she, also, is forgotten.

Babylon was remarkable for the two beautiful palaces, one on each side of the river, and the great temple of Belus. Connected with one of these palaces was the hanging garden, regarded by the Greeks as one of the seven wonders of the world, but that was prior to the erection of the Washington monument and civil service reform.

This was a square of 400 Greek feet on each side. The Greek foot was not so long as the modern foot introduced by Miss Mills, of Ohio. This garden was supported on several tiers of open arches, built one over the other, like the walls of a classic theatre, and sustaining at each stage, or story, a solid platform from which the arches of the next story sprung. This structure was also supported by the common council of Babylon, who came forward with the city funds, and helped to sustain the immense weight.

It is presumed that Nebuchadnezzar erected this garden before his mind became affected. The tower of Belus, supposed by historians with a good memory to have been 600 feet high, as there is still a red chalk mark in the sky where the top came, was a great thing in its way. I am glad I was not contiguous to it when it fell, and also that I had omitted being born prior to that time.

“When we turn from this picture of the past,” says the historian, Rawlinson, referring to the beauties of Babylon, “to contemplate the present condition of these localities, we are at first struck with astonishment at the small traces which remain of so vast and wonderful a metropolis. The broad walls of Babylon are utterly broken down. God has swept it with the besom of destruction.”

One cannot help wondering why the use of the besom should have been abandoned. As we gaze upon the former site of Babylon we are forced to admit that the new besom sweeps clean. On its old site no crumbling arches or broken columns are found to indicate her former beauty. Here and there huge heaps of debris alone indicate that here Godless wealth and wicked, selfish, indolent, enervating, ephemeral pomp, rose and defied the supreme laws to which the bloated, selfish millionaire and the hard-handed, hungry laborer alike must bow, and they are dust to-day.

Babylon has fallen. I do not say this in a sensational way or to depreciate the value of real estate there, but from actual observation, and after a full investigation, I assent without fear of successful contradiction, that Babylon has seen her best days. Her boomlet is busted, and, to use a political phrase, her oriental hide is on the Chaldean fence.

Such is life. We enter upon it reluctantly; we wade through it doubtfully, and die at last timidly. How we Americans do blow about what we can do before breakfast, and, yet, even in our own brief history, how we have demonstrated what a little thing the common two-legged man is. He rises up rapidly to acquire much wealth, and if he delays about going to Canada he goes to Sing Sing, and we forget about him. There are lots of modern Babylonians in New York City to-day, and if it were my business I would call their attention to it. The assertion that gold will procure all things has been so common and so popular that too many consider first the bank account, and after that honor, home, religion, humanity and common decency. Even some of the churches have fallen into the notion that first comes the tall church, then the debt and mortgage, the ice cream sociable and the kingdom of Heaven. Cash and Christianity go hand in hand sometimes, but Christianity ought not to confer respectability on anybody who comes into the church to purchase it.

I often think of the closing appeal of the old preacher, who was more earnest than refined, perhaps, and in winding up his brief sermon on the Christian life, said: “A man may lose all his wealth and get poor and hungry and still recover, he may lose his health and come down close to the dark stream and still git well again, but, when he loses his immortal soul it is good-bye John.”

Lovely Horrors

I dropped in the other day to see New York’s great congress of wax figures and soft statuary carnival. It is quite a success. The first thing you do on entering is to contribute to the pedestal fund. New York this spring is mostly a large rectangular box with a hole in the top, through which the genial public is cordially requested to slide a dollar to give the goddess of liberty a boom.

I was astonished and appalled at the wealth of apertures in Gotham through which I was expected to slide a dime to assist some deserving object. Every little while you run into a free-lunch room where there is a model ship that will start up and operate if you feed it with a nickle. I never visited a town that offered so many inducements for early and judicious investments as New York.

But we were speaking of the wax works. I did not tarry long to notice the presidents of the United States embalmed in wax, or to listen to the band of lutists who furnished music in the winter garden. I ascertained where the chamber of horrors was located, and went there at once. It is lovely. I have never seen a more successful aggregation of horrors under one roof and at one price of admission.

If you want to be shocked at cost, or have your pores opened for a merely nominal price, and see a show that you will never forget as long as you live, that is the place to find it. I never invested my money so as to get so large a return for it, because I frequently see the whole show yet in the middle of the night, and the cold perspiration ripples down my spinal column just as it did the first time I saw it.