Полная версия:

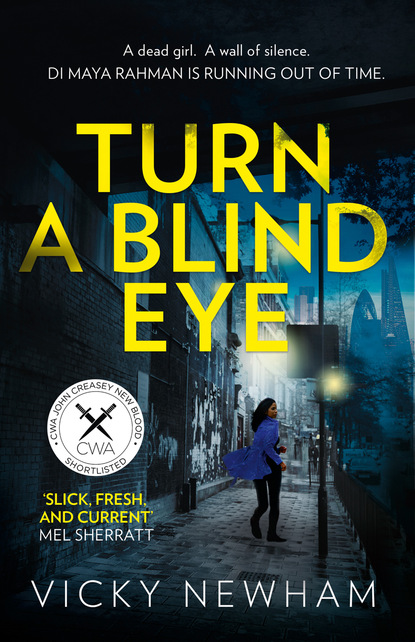

Turn a Blind Eye

In the chilly air of the flat, steam trails upwards from the saucepan as Mum stirs it. The walls round the cooker shine with condensation.

A few minutes later Sabbir arrives, with bed-head hair and sleep furrows in his bruised cheek. ‘What’s for tea?’ He glances round the kitchen.

We all know the answer, but each day we hope it might be different. We love Mum’s cooking, but after eight years of school dinners, and tea sometimes at friends’ houses, we’ve got used to eating different food. Perhaps Dad will come home with a treat for us all? A bagel each from the shop in Brick Lane, or some red jam to have on sliced bread?

‘Rice and curry,’ Mum says. She always talks to us in Sylheti, and at home my sister and I speak our mother tongue too. Unless, of course, it’s something we don’t want Mum to hear.

‘It’s the second power cut this week, isn’t it?’ Sabbir is the eldest of the three of us.

Mum serves out the stodgy rice and curry, and passes bowls over one by one. ‘Careful. They’re hot.’ All seated round the table now, Dad’s chair sits empty, no bowl on his place mat, just cutlery and an empty water glass. ‘We may as well eat. Your father’s obviously got held up again.’ The words ride a sigh.

My socked feet are cold. I like it when I can rest them on Dad’s work boots. Get them off the cold concrete and warm them up.

Just as we’re finishing our tea, we hear the front door bang shut downstairs, and a few moments later the grinding sound of a key in the flat door. Dad comes in, bringing a whoosh of bitter winter air and cigarette smoke, and another smell I’ve noticed before. The draught pulls the candle wick first one way then the other, and Mum jumps up to shield Sabbir from the billowing flame, bashing the table and knocking over her water glass. She uses a tea towel to mop first the water then the gash of wax that’s run onto the shiny tablecloth.

‘While we’ve been here with no power, you’ve been in that pub again. I can smell it.’ The reproach is unmistakeable. ‘This is the last candle. We need more. The children can’t sit in the dark.’

Dad looks at Mum, and then shines his gaze like a torchlight round the table. Pauses.

I’m watching him. Wondering what he’s thinking and what’s going to happen. I grab Jasmina’s hand under the table. He looks over at the hob, then back to the table. The room shimmers with tension and it makes my skin prickle. Every day now, Dad’s late and Mum says the same thing. He must be tired and hungry after working all day, but it’s as though there’s more to him going to the pub than either of them mentions.

Dad lets out a long sigh, like letting air from a balloon while holding on to its neck. In the soft light, his cheek muscles quiver. ‘I’ll go and get some now.’ He and Mum whisper to each other in very fast Sylheti.

My breathing tightens.

As he turns, I get another waft of that smell, the one his clothes so often reek of. ‘Won’t be long,’ he says in English.

I feel a swirl of something in my stomach, pulling at me. I put down my spoon. I don’t want Dad to go out again. He’s home now and it’s cold. I look into his face, with its gentle creases, the dark growth round his face, and his large eyes the colour of conkers.

‘Dad?’ I can’t help saying. I don’t know why.

‘You children be good for your mother,’ he says sternly, and ruffles my hair with his hand. When he stops, he lays his palm flat on the top of my head for a second, and I feel momentarily held in his warmth before he removes it. He gabbles something else to Mum in Sylheti, his voice even lower than usual. A jumble of sounds, noises, tones.

I squeeze Jaz’s thumb. Use my eyes to plead with her, but she shrugs and shakes her head.

Before I know it Dad pulls the flat door behind him and the latch clicks shut. He never even took off his coat and now he’s gone.

Mum’s spoon drops from her hand and clatters on the bowl in front of her. She closes her eyes, sucks in a long breath and lets it out, at first with a low moan, like an animal in pain, then in a full-throated wail.

‘Mum?’ She’s never made a noise like this before. ‘Are you okay?’

Sabbir’s chair screeches on the hard kitchen floor as he pushes it back to stand up. ‘Okay. Let’s all play a game.’

I know something’s happened, but have no idea what. ‘Dad will be back soon with the candles, won’t he? We can finish our homework then. I’ve got English to do and Jaz —’

‘We can play ’til then.’ Sabbir looks over at Mum, and I follow his gaze.

She’s sniffing, dabbing her nose and fanning herself with her hand. ‘I’m fine,’ she says, her voice faltering. ‘Just give me a minute.’

But I can still hear that moan in my ears and I know we can’t leave her.

‘How about we get the blankets from our bedrooms and put them on the floor in here?’ It’s Jasmina. ‘If we push the table over, we can make a camp. Mum?’

Excitement bubbles up. I love camps. ‘We could sleep down here too.’

‘We may have to if the power doesn’t come back on soon,’ says Mum.

Five minutes later, Jaz, Sabbir and I have fetched our bedding from upstairs. Mum has cleared away the dishes and pushed the table against the wall. On the gas hob a pan is heating for our hot water bottles. We pile cushions onto the eiderdowns and clamber on top. Our bottles filled, Mum joins us, but with her back against the wall and her legs under the covers.

‘Tell us about Bangladesh again,’ I ask Mum. ‘What was it like growing up outside the city?’ All three of us love to hear her stories. We’d lived in the city centre of Sylhet so this part of our home country wasn’t something we knew well.

Mum speaks slowly as though she’s combing through her memories and putting them in place. Hearing her speak in Sylheti feels completely natural. Comforting, somehow. It’s like being in our old flat by the river.

‘One of my favourite things was the rolling hills. The land often flooded, especially in the monsoons, and lakes formed on the flood plains. Sometimes your grandfather took us into the swamp forests by boat. They’re magical places where trees grow out of the water. Their branches join up at the top to form canopies and tunnels.’ Mum gestures with her hands.

In the soft candlelight I catch the look on her face, as though the memories bat her back and forth between pleasure and pain.

‘Living here in London, in the cold and grey and the dark, I miss life by the river and the lush green colour. After the monsoons, beautiful star-shaped pink water lilies would float on the lakes. Sabbir, d’you remember the migratory birds? You always loved the swamp hens, didn’t you?’ Her melancholy makes me wonder how she feels about us moving to Britain. ‘The tea estates are glorious,’ she says, making a sloping gesture with her arms. ‘Carpets of green bushes, all trimmed to waist height. My mother and her sisters would pick the tea. I went once to help.’ The soft candlelight melts the ache in her features. It warms her voice for the first time this evening. ‘My father’s family grew rice.’ Energy builds in her voice. ‘I liked to watch the buffalos treading on the rice hay to dislodge the grains. It’s the traditional way of doing it. Afterwards we’d all swim in the Surma, and watch the cattle as they drank in the river. They’re —’

The flat buzzer silences her, and we all jump. Wrenched from the vivid colours of Bangladesh back to our dark kitchen.

‘Who’s that, ringing at this time?’ Mum’s tense again.

‘Perhaps Dad’s forgotten his key?’ It’s all I can think of. ‘I’ll go.’ I get up and feel my way to the hall, my eyes used to the dark. I open the door, expecting Dad to rush in, laden with bags, full of apologies and jokes and stories.

But there’s no-one there.

‘Who is it, Maya?’ Mum shouts through.

‘No-one. Someone must’ve pressed the wrong bell.’ I step outside the flat into the hall and, smelling tobacco, I scour the darkness for a glowing cigarette end or the light of a torch. My foot knocks against an object on the ground. There’s something beside the doorway. I lean over to feel what it is. A plastic bag rustles in my fingers. In it is something hard, like a cardboard box. I pick up the package and carry it into the flat.

‘Someone left a parcel.’ I place it on one of the kitchen worktops.

‘At the door?’ That tone is back in Mum’s voice. ‘For pity’s sake, Maya —’

‘No-one was there, just this bag.’ I point, although it’s obvious.

‘Give it to me,’ says Mum sternly, moving towards the worktop.

But Sabbir has already begun rummaging in it. He looks at us all in turn, his face excited. ‘It’s candles and . . . you’re never going to guess what . . .’

‘Bagels?’ Jasmina and I shout in unison.

Wednesday – Maya

When I got home and closed the front door, relief surged through me. It wasn’t my brother’s photo in the hall that brought the tears, nor the suitcase I’d parked by the stairs when I arrived home in the early hours. It was that, all day, my attention and energy had been on the investigation when what I wanted was to be alone with my grief. Now, I finally had the chance to gather it up so I could feel close to Sabbir; to wade through all the conflicting emotions about how he’d died – and why.

In the kitchen, I lobbed my keys onto the worktop, followed by the soggy bag of chips I’d half-heartedly collected on the way home. In the cold air, the smell of malt vinegar wafted round the room and the greasy mass was unappealing. I flicked on the heating. Next to the kettle, the message light was flashing on the answerphone. Mum had probably forgotten I’d gone to Bangladesh for the funeral.

Through the patio doors, the light was reflecting on the canal water in the dark. When I was house-hunting, I’d had my heart set on this flat as it reminded me of Sylhet and our apartment there when we were growing up. I remembered how sometimes, when he’d been in a good mood, Dad would sit between Jasmina and me on our balcony there and read us the poems of Nazrul Islam. On those rare occasions, the two of us would lap up the crumbs of Dad’s attention, bask in his gentle optimism, oblivious to the stench of booze and tobacco on his breath, and the smell of women on his clothes and skin.

What I remembered most, though, was how yellow his fingertips were; the feel of his cracked, dry skin. And how much I’d loved his burnt-caramel voice.

I headed into the lounge. Last night’s array of mementos littered the coffee table, waiting to be stuck into the journal I’d bought from the market in Sylhet. The fire had destroyed most of Sabbir’s belongings so Jasmina and I had chosen what we wanted from the bits that were recovered. My eyes fell on the book of Michael Ondaatje poetry. He’d annotated it. On the plane home, I’d read every single poem and pored over all my brother’s notes, then wept in the darkness of the cabin. I’d learned more about Sabbir from those poems than all our conversations.

Sometimes the canal outside was soothing. Tonight, although the water was still, I felt it pressing in on me. Unable to shift Linda’s death from my mind, I kneeled in front of the wood burner. As I lay kindling on the bed of ash, my thoughts drifted back to the amalgam of conversations from earlier in the day. I was exhausted. A combination of jet lag, lack of sleep and not eating. I was contemplating having a bath when my mobile rang. It was Dougie.

‘Hey, how are you?’ We’d Skyped several times when I was in Bangladesh but, other than seeing him at the crime scene, I hadn’t had the chance to catch up with him since getting back. He was downstairs, so I buzzed him in and went to meet him at the door, pausing briefly to check my appearance in the mirror.

‘I was on my way home. Wanted to check you’re okay.’ He leaned over and his beard growth brushed my cheek as he gave me a kiss.

I drank in the smell I knew so well, and, for a moment, I longed to sink into his arms. ‘Shattered, but pleased to see you. Come in.’ I began walking away from the door. ‘I was going to call you.’

He followed me along the hall and into the kitchen. Pulled the overcoat off his large frame and draped it over a chair back.

‘Fancy a beer?’ I said.

‘If you’re having one.’

I took two bottles from the fridge and passed him one.

‘You’ve met the fast-track sergeant, then.’ He took a swig of beer.

‘Yeah.’ I sighed, irritated. ‘Briscall must’ve known about this for a while. Nice of him to mention it.’

Dougie’s bushy eyebrows shot up. ‘That man’s a prick.’ He strode over to the window and back. ‘Gather this Maguire bloke’s an Aussie? What’s he like? Have to say, he looks more Scottish than I do.’

‘He seems a good cop. Knows his stuff and he’s pretty sharp in the interview room. Briscall will never change. I had a lot of time to think when I was in Sylhet and I’m done with letting him wind me up. I joined the police to make a difference, and to help people like Sabbir. I’m fed up with Briscall side-tracking me with his petty crap.’

Dougie had one hand round his beer, the other in his pocket. He was taking in what I was saying. ‘How’s it going with the school and the Gibsons? It’s all over the media.’

‘No real leads. We’re waiting to interview two key witnesses. One’s under medical supervision, the other’s gone AWOL.’ I groaned with frustration. ‘We’re still puzzling over the Buddhist precepts. There are five of them. Why the killer has started with the second, we don’t know.’ The cold had reached my bones today and I needed to warm up. ‘Shall we go through? The stove’s on.’

In the lounge, Dougie sank into the sofa, his manner quiet and reflective.

‘As a murder method, what d’you reckon strangulation says about the killer?’

‘I’m not sure.’ He paused to think. ‘It’s quick and doesn’t require any weapons. Silent apart from victim protests. Excruciating agony for a few seconds, depending on the pressure, then the victim slips into unconsciousness. Death minutes after that. It’s certainly different from stabbings and shootings.’

I was nodding. ‘On training courses we’re continually told that murder methods are rarely random or coincidence, except in the heat of the moment. Whoever murdered Linda chose to strangle her, bind her wrists and leave a message by her body.’

Dougie was stroking his chin. Silent for a few moments. ‘It’s certainly symbolic. Whoever did it could’ve simply strangled her and left.’

The material that had been used to bind Linda’s wrists wasn’t expensive, but Dougie was right: for the killer to bother, it must symbolise something for them. And forethought had gone into what they had chosen to write. It wasn’t an impassioned scrawling of ‘BITCH’ across a mirror in red lipstick, for example.

‘The most logical explanation is that the two acts go together.’ I held my forearms the way Linda’s had been positioned. ‘The precept says, I abstain from taking the ungiven. If your wrists are tied, so are your hands.’

‘Bingo. You can work from there. Although, hang on.’ Dougie placed his beer on the coffee table. ‘Did you say there are five precepts? Do you think the killer’s started with the second precept because of its significance? Or do you suppose there’s been a murder before this one?’

Wednesday – Dan

The Skype ring tone danced around the small bedroom. ‘Pick up, pick up,’ Dan urged, as he pictured the early morning scene at home in Sydney: Aroona getting the girls ready for whichever club or friend they were going to today. It was nearly midnight and Dan was wide awake in his Stepney flat-share. Every cell in his body felt as though night-time had been and gone. He lay beneath his crumpled coat, shivering, longing for the unbearable heat of home.

On his phone the pixelated image solidified. ‘Daddee,’ came Kiara’s squeal through the ether, and the video clicked in. She had a huge grin on chubby cheeks, her face still full of sleep.

‘Hey, kiddo. How are you?’ Dan searched her features for tiny signs of change, drinking up their familiarity. ‘I really miss you guys.’

‘Is it cold there? Mum said you’ve got, like, minus twenty or something.’

Dan chuckled. Swallowed the lump in his throat. Her innocent exaggeration was refreshing. ‘Not quite. It is cold, though, and we’ve had a bit of snow.’ It was so good to hear her voice. ‘Did you go to the beach yesterday?’

Another face bombed the picture. Sharna. All soft curls and gappy teeth. ‘Snow? Take some photos.’ A gaping mouth loomed in, and she attempted to point at her gums. ‘The toof fairy came last night, Daddy.’

‘Is that right? What’d she bring?’

‘A new toofbrush.’

Both girls dissolved into giggles. It was a typical Aroona present.

Homesickness pinched at Dan. Being apart from his family and missing out on milk teeth and swimming lessons . . . He hoped they’d all be able to join him soon.

‘Mum’s coming,’ said Kiara. ‘I got burned today. I’m all scratchy.’ She rubbed at her neck and face as though needing to make her point.

He’d only been away four months. Living in Sydney, he was used to hearing an eclectic mix of accents, but the combination was different in East London. The familiar Aussie vernacular was comforting but sounded different from the way it normally did. More distinct.

Feet shuffled across the laminate of their apartment. Aroona peered over the top of the girls’ heads, her dark hair a contrast with Sharna’s blonde and Kiara’s red.

‘Hey,’ Aroona said. ‘How come you’re still up?’ She was holding a giant tub of mango yoghurt with a spoon in it, and in the background the TV was blaring out the weather in New South Wales.

‘Oh, you know. Wanted to speak to my girls.’ Around him, magnolia walls were devoid of home touches. On the floor beside his bed, the greasy KFC box reminded him how hungry he was. He brought his wife up to date with Maya’s return. ‘I’m still trying to find a proper apartment.’ He wanted to ask if she’d thought further on when she and the girls would join him, but didn’t want to upset the geniality of their conversation. Things were shifting for the Aboriginal communities and he knew how much Aroona cared about helping them. ‘I’ve heard about the tooth fairy. How did the swimming lessons go?’

In front of him the girls squirmed and giggled.

‘She did very well and —

Her reply was drowned out by a banging on the flimsy party wall of Dan’s room. ‘Trying to sleep here, mate!’ boomed the voice of the flatmate he’d heard but never met.

‘I’d better go,’ Dan hurried, irritation bubbling in his throat. ‘It’s late here. Speak soon, Okay?’

They waved and he cut the call.

Emptiness seeped back into the confines of his tiny room, silence back into the yawning space. And on his phone, from the background image, Aroona and the girls beamed at him.

Thursday – Maya

During the night it had snowed and, when I left the flat at 7 a.m., a dusting of white crystals lay on the path by the canal and on the lock. It was as though the world at the water’s edge had been cleaned. From there, my walk to the car took me past the graffiti tags on the bridge at Ben Johnson Road, and the burned-out shell of a warehouse, with its blackened brickwork and boarded-up windows. Overhead, bulging black snow clouds hung over Mile End like baggy trousers.

All night I’d been unable to shift the idea that there may have been a murder before Linda’s. I’d emailed the team and asked Alexej to check all suspicious deaths from the last three months, involving calling cards or anything ritualistic.

I was soon in Stepney, outside the block of flats where the Allens lived; an ugly, seventies-built, three-storey building. Paint was flaking off tired metal windows. On both sides of the entrance the recent snow was melting on mud, and discarded fag butts were leaking brown into the white slush. I rang the buzzer. Nearby, a yellow crane was lowering a vast steel structure onto what used to be playing fields, and I had to raise my voice over the drone and beeping of the site JCBs.

‘I’m DI Rahman,’ I shouted into the intercom.

Roger Allen buzzed me in and met me at the door of his flat. Stale alcohol fumes wafted towards me. I recognised him from the staff photos but hadn’t absorbed quite how skinny he was. Speckled stubble growth clung to his face. Shirt tails trailed over his trousers and his jumper was lopsided.

‘Did you get the messages to contact us?’ It was more of an accusation than a question. ‘We came round here yesterday and rang several times.’

A startled look swept over his features. ‘Sorry. My wife did tell me. I’ve been . . .’ He broke off; looked over his shoulder into the flat and then back to me.

‘I assume you know that Linda Gibson was murdered yesterday?’ People who wasted police time really pushed my buttons. It was one of my most regular rants to the team.

Roger opened his mouth to speak and closed it, as if weighing up what to say. ‘Yes, I do. But I don’t know anything about it, I’m afraid.’

A draught was making its way down my collar. ‘May I come in?’ I gestured to the flat and moved towards the open door.

Roger glanced at his watch.

‘Got to be somewhere?’ My patience was withering.

He rubbed his balding head and stepped reluctantly back inside, gesturing for me to enter.

Down the hallway a television was blaring. There was something familiar about the output. In the hall, a holdall stood up against the wall and a man’s jacket hung on the bannisters. A pair of pink wellies nestled on the laminate next to an assortment of family shoes. The hall table was cluttered with toys and a toddler’s trike had been parked under the hall table. The smell of toast wafted out from the kitchen. So, he was in the middle of his breakfast – but why did he look like he’d spent the night on the sofa?

Roger led me into the lounge where the television was on.

Of course. It was the school video. I pointed at the source of the noise, and raised my voice over it. ‘Could you mute that?’

He scanned the room for the remote control and zapped the TV off.

‘Do you usually watch the school video before you go to work?’

He jutted his chin in defiance and slid the remote control onto the coffee table. ‘Course not. I was just checking something.’

‘Checking what?’

‘The . . . the sound.’

I stared at him in disbelief. ‘Alright to sit down?’ I perched on an armchair and took out my notepad. I needed to change tack; get Allen off the defensive. Attempting to make my tone of voice less impatient, I said, ‘An officer came round here yesterday afternoon. I called round on my way home last night. On both occasions your wife said you were out.’ I raised my voice at the end of the sentence, to imply the question rather than state it. He was a bright man. He knew what I wanted to know.

‘Yeah, I popped out for some fresh air.’ He cocked his head and stared at me.

‘Both times? Did you get the messages to call us urgently?’

‘I . . .’ He was standing in front of the fireplace, his attention fixed on his hands, pulling at them as if they were lumps of dough.

In that moment, I felt sorry for him. I tried to imagine this man, in his scruffy clothes, conducting management meetings at school, leading working parties and standing in front of assemblies. I changed the subject. ‘Who’s off on their travels?’

‘Eh?’ Roger’s eyes darted round the room.

‘The bag in the hall?’

‘Oh, that.’ He waved his hand in the air dismissively. ‘We haven’t put it away yet. A Christmas trip.’ He was fiddling with his wedding ring now, twisting it round his finger as though he were trying it on for size.

That was about as convincing as his account of why he’d been out when the police came round. I surveyed the room.

Family-worn furniture.

Drinks tables.

Several lamps.

Cheap sound system. Nothing out of the ordinary so far.