Полная версия:

Two Suns

Thus, a new chapter in the family's history began. At home, Anna diligently cared for her mother, managed the household, and attended typing courses, while Mark found employment in his father's artel. The years of revolution and war communism had left many buildings dilapidated, necessitating not just repairs but restoration as well. Simultaneously, new constructions were unfolding, leading to numerous orders for their brigade. The team was friendly, and Baruch, the leader, meticulously selected personnel based on reliable recommendations, ensuring smooth holidays and the observance of the Sabbath.

In the evenings and on weekends, Mark took the opportunity to explore the unfamiliar cityscape. Following a self-imposed rule, he ventured from the center, the Kremlin, into different directions, acquainting himself with the city, its customs, and its habits – traversing on foot or aboard streetcars like a true Muscovite. Everything was new and surprising, but when he reached the Moskva River, the bustling wharves reminded him of his native port, and he felt at home.

His exploration initially centered on the neighborhoods of Sretenka and Meshchanskaya Sloboda, where intricate facades of revenue houses stood alongside sturdy stone buildings from the last century and wooden two-story shacks inhabited by a diverse and often unreliable population. The Sukharevsky market was a place to be cautious about, and Anna was strictly forbidden from going there alone. Yakov also warned his son, «Don't venture in there unless necessary; it's not a place for leisure. And keep a close eye on your pockets!»

As understandable as his father's instructions were, they proved challenging to follow in practice, given that nearly all roads led through the market. The adjacent streets, filled with shops, stores, and inns, were essentially an extension of it. Yet, the newly minted Muscovite found this unusual place fascinating. He visited as if attending the movies, gaining experience from the sights and sounds. And when he sensed suspicious glances – «he's prowling around, seeking out a thief; there are plenty of hooligans now» – he would cautiously retreat, imagining himself as a protagonist of a detective story. There was something elusive that drew him to the market.

One Sunday, as he strolled along the rows, he heard a sudden commotion behind him – shouting, whistling, and cursing, as if a wave of chaos was approaching. From a distance, Mark had witnessed such occurrences before. As he turned around, he saw a boy emerging from the sea of people, pushing him, and then disappearing into the crowd. Mark could have apprehended the hoodlum, but for an instant, their eyes met, and he found himself frozen. Following closely behind was a policeman, shrilly whistling, and a short while later, a panting, bewildered, heavy-set citizen arrived.

The scene played out as a typical occurrence in the market. Mark noticed that no one else in the crowd seemed bothered, and life resumed its normal pace. Nevertheless, the weight in his pocket felt unusual, prompting him to reach for the source of the heaviness.

Once out of the crowd, he ducked into the first alley to examine the «foundling» – a costly cigarette case. «What should I do? Should I go to the authorities?» he pondered, feeling perplexed. He couldn't understand why he refrained from apprehending the thief, a blueeyed, attractive young man who appeared to be around his age. There was something in the thief's gaze that halted him – perhaps slyness, as if they were comrades sharing a secret, or an undeniable, composed seriousness. Mark was certain that he wasn't going to take any action. Was it compassion, a sense of camaraderie, or maybe fear of the consequences, knowing the ways of the local public? Whatever it was, fear wasn't what he felt.

«Discard it! Toss it away and forget it,» his self-preservation instinct whispered, urging him to make the sensible choice. But he couldn't bring himself to do it. Instead, he secretively stashed the cigarette case under the mattress at home. A surprising thought crossed his mind: «This is my first secret…» Strangely enough, within the friendly Maretsky family, secrets, even when they surfaced (mostly about the boys' mischief), had a tendency to be revealed swiftly.

He hadn't yet decided what to do with the stolen item, but from that day on, every time he passed through the market, he searched for the pickpocket. Mark couldn't help but wonder if the thief had been caught on that ill-fated morning. Nights were spent restlessly, cursing himself for unwittingly becoming an accomplice.

A week or two later, while leaving the house, Maretsky nearly collided with the blue-eyed pickpocket.

«Sacha,» the unpunished thief introduced himself briefly, extending his hand.

Mark introduced himself and shook the grubby, five-fingered hand. Surprisingly, a sense of relief washed over him – he saw a way out of the delicate situation.

«Why didn't you report me? I could've been caught,» the pickpocket inquired, studying Mark with unabashed interest.

«I had second thoughts,» Mark admitted, realizing that he indeed had.

«Well, I'm grateful,» the pickpocket remarked jokingly, extending his gratitude. «Where's the item? Did you get rid of it already?»

«You're insulting me! It's right there, waiting for you. Let me get it for you.»

When the item was returned to its rightful owner, Mark finally breathed a sigh of relief. Sacha inspected the cigarette case and expressed his dismay:

«Oh, what a waste of effort. And it was such a serious gentleman.»

«What's wrong?»

«I don't believe it's gold. Well, I might get a few pennies for it, at least.»

As they strolled together towards the square, Mark couldn't help but ponder how this newfound acquaintance defied the stereotypical image of a street thief. Sacha was a blond, well-built but notably thin young man with delicate features and an exceptionally smooth way of speaking. Something about him didn't quite add up.

Nevertheless, that day marked a significant turning point for Mark – unexpectedly, he had found a friend.

* * *The more Maretsky got to know Sacha, who happened to be a year younger than him, the more he understood why he hadn't reported him. Sacha Voisky hailed from Tver, born to an officer in a destitute noble family and a former maid. He recounted his life with a subdued demeanor, devoid of any emotion.

«The last time I saw my father was in 18. He returned from active duty, from the war. It was barely a week, and then he left to fight again, this time against the Bolsheviks. He assured me he'd be back soon, said they wouldn't last long,» Sacha paused for a moment. «But you see how it turned out… He vanished, and I haven't heard from him since.»

While such a narrative was sadly common during those times, it remained no less tragic. His mother was left grappling with desperate attempts to find work. Eventually, she fell in with a lover, a shadowy figure who elicited persistent disdain from the young boy. This new «father» coaxed them into relocating to Moscow.

Once in Moscow, the stepfather engaged in dubious dealings in the Sukharevsky market and soon got carved up, right in front of Sacha's mother. Since then, as his newfound friend recounted, she had been «a bit out of sorts,» and Sacha took on the role of the sole breadwinner.

* * *Despite living in different worlds, the two young men shared much in common: their curiosity and hunger for new experiences led them to seek out and discover the wonders of the big city. Although Sacha held some disdain for Moscow, he acknowledged its abundance of attractions – movies, theaters, museums, and the plethora of newspapers and magazines. Their mutual passion for reading connected them effortlessly. Mark undeniably lagged behind Sacha, the latter being reared under the vigilant guidance of his father from his tender years. And Mark admired Sacha's remarkable memory; he could remember the contents of all the books he had read and could even quote from them. They often exchanged books, though it seemed that Sacha had somehow acquired some rare volumes from the Sukharevsky market.

By that time, Mark had been toiling at the brickyard, having joined the school of the working youth, and he convinced Sacha to do the same, persuading him that his intellectual prowess warranted pursuing higher education at an institute.

«Are you kidding me? You want me to become part of the working youth?» Sacha sadly protested.

«Well, first you'll have to get a job at the factory. I'll ask around. I think Baruch has a brother-in-law at the candy factory. I'll also ask my foreman. But it might be tough for you at the brick factory,» replied Mark.

«I'm not afraid of hard work. But don't you see? I'm disadvantaged!» argued Sacha.

«What kind of nonsense are you talking about? Nobody here knows about your father,» Mark playfully jested. «And besides, why would you consider yourself disadvantaged? You have everything.»

«What do you mean, 'everything'?» Sacha slyly squinted and tapped his forehead. «What about this?»

«That's exactly what I'm saying! You've got a brilliant mind!» Mark emphasized.

«Maybe we should seriously give it a try,» Sacha finally conceded.

Mark was delighted; it seemed he had successfully convinced his friend. However, Sacha's shenanigans did not hold much appeal for him. Besides, the New-Sukharevsky market, with its orderly rows of stalls and vigilant guards, was a far cry from a place he found enjoyable.

Meanwhile, Sacha was captivated by the idea of pursuing higher education. He began making plans, yet remained undecided about his future. He felt he could excel at anything he put his mind to.

Unfortunately, fate had other plans. On a warm April evening, the two friends attended an operetta that had opened six months prior – a musical performance of Dunayevsky's Grooms. Although it was a comedy, Sacha was preoccupied with worries about his mother, who had been drinking heavily with a neighbor the previous day.

The performance ended late, and as Sacha returned home, he noticed a commotion near his house. Smoke and flames emerged from the cellar window where he and his mother resided in a tiny room. Fueled by desperation, he pushed through the crowd to reach the burning building. Despite attempts to hold him back, he broke through the fire. Tragically, a burning beam collapsed at that moment. The firemen managed to rescue him, but he was left unconscious and severely burned.

For three days, Mark visited both patients in the emergency room. His mother had been struggling with another course of treatment for two weeks, while Sacha remained unconscious due to his injuries. And thus, Mark lost his best friend…

The trees along the boulevards were veiled in a green haze, and the air carried the intoxicating scents of young leaves, freshness, and damp earth, along with something intangible and exhilarating. This time of year always held the promise of something new, something positive – a sense of renewal. And yet, it was also a time of profound loss!

Mark wandered the streets in a daze. Despite his naturally optimistic disposition, always meeting difficulties with a smile, he felt utterly bewildered. The tragic loss of his best friend had taken him by surprise, leaving him emotionally disoriented. Even his beloved books, which had always been close companions, couldn't provide solace during this trying time.

Witnessing his son's profound distress, the seasoned Yakov shared his wisdom:

«Life goes on, my son. You have to carry on despite the pain of loss. It'll hurt, and that's something you'll have to live with. But believe me, only hard work can ease that pain, little by little, yet it will never completely vanish.»

Mark, on the verge of tears, looked up at his father. The words continued to flow:

«So, all I can advise you, my son, is to work diligently, study diligently. Don't give up, no matter what challenges come your way. And be prepared for other losses that life may bring.»

«Daddy, is this your way of comforting him?» Anna was taken aback by her father's unexpected speech.

«I'm not trying to comfort him. Everyone has to find their own way to cope. I'm simply trying to prepare him for the realities of adulthood,» Yakov explained.

«I understand now, Dad. Thank you,» Mark replied gratefully.

* * *Two years later, Maria also passed away. With his school days behind him, Mark felt a newfound clarity of purpose. He could now embark on his journey to Leningrad, where his dreams of the sky beckoned him.

Beloved little sister, who was experiencing a difficult farewell, and their father remained in the capital. But for Mark Maretsky the Moscow chapter of his life had come to an end, and in that moment, it seemed as if it were for good.

Chapter 8: «To Moscow…» and in Moscow

The Mirachevsky newlyweds' journey to Moscow took them through the Southern Railway Station in Kharkov, one of the largest in the former Russian Empire, where they had to make a transfer. After enduring several tedious hours at the station, they finally found themselves aboard the train. Olga, exhausted by the dramatic events of the past twenty-four hours, was slowly dozing off…

Her life up until that point had been a challenging struggle for survival. They lived in a rented apartment with the girls as dormitories were scarce, and those fortunate enough to secure a spot were not to be envied. The new authorities strangely allocated the most unsuitable premises for students in Kiev: the former museum of Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra, barracks once housing prisoners during the war, and even St. Michael's Golden-Domed Monastery, now devoid of its famous gilding, was converted into a dormitory. A sign on its gates read: «Housing for proletarian students.» Olga had to visit her classmates there and recalled the narrow cells and the cheerful, despite cramped conditions, residents.

Leonid gazed at his wife («wife!» – he enjoyed using that unfamiliar word) and tried to discern her thoughts. He was well aware of Olga's reserved nature; even in her school years, she sometimes appeared older than her peers.

«But how frightened she was at the station! And not for herself, that's for sure.» He realized with astonishment that he was grateful to that country boy, the rejected suitor, for the dangerous incident that had revealed Olga's feelings, of which Mirachevsky had, perhaps, not been entirely sure until then. Yes, she was pleased. Yes, she had accepted the «marriage proposal.» They got married. But his passionate temperament craved more. Now, the events of yesterday's fright unequivocally proved that their love was mutual.

«What are you pondering?» Leonid's question came so unexpectedly that Olga flinched.

Unsure of how to express herself, she didn't respond right away:

«Perhaps, about the peculiarities and twists of fate.»

He understood, of course. He was contemplating the same thing himself. But he wanted to uplift her spirits, so he asked with mock indignation:

«Are you calling our marriage a twist of fate?!»

«Well, if you think about it, we're truly stepping into a new life right now, at the gates…»

«Wow! That's what a degree in philology gets you – the ability to string words together like that! I wouldn't have thought of that. But it's late; let's get some rest.»

* * *The unpleasant residue of the incident at Lazirky station finally dissolved as the train slowed down and glided through the Moscow suburbs, and Olga's heart fluttered with excitement: «To Moscow, to Moscow…»

The Bryansk railway station, the southwestern gateway to the capital, was initially dominated by the imposing platform – Mirachevsky couldn't help but grin as his wife descended to the platform, visibly astonished by the glass-and-steel structure spanning over the tracks. The place erupted with loud exclamations, spiraling into the vortex of customary commotion, with helpful porters weaving through the fray, leading to a bustling square teeming with individuals, carriages, and assorted vehicles.

For Olga, the first sign of their new life was a ride in a taxi-car, a recent addition to the capital's transportation.

Leonid whistled for the porters and hurried towards the bus stop, suggesting, «Let's go for a ride! It's a pity we won't catch a breeze.»

«How far is it?» Olga asked.

«Not that far. Are you tired?» asked Leonid, sensing her agitation.

«A little.» Olga was really out of her depth.

«But, Madame Mirachevsky,» he playfully bowed, «you'll get a glimpse of the city.»

They hopped into a sleek black car with a yellow stripe on the side and a canvas top, gracefully maneuvering through the crowd as they crossed the Borodinsky Bridge and ventured farther into the city. «Here is the Moscow River! The Garden Ring!» proudly narrated the aspiring railroad engineer. «He seems to excel as a tour guide too!» Olga couldn't help but admire her husband in every way.

Soon, the car entered a serene alley, and the bustling city noise vanished as if it had never existed. As they reached the final destination of their journey, Leonid's home in Tryokhprudny Lane, the vastness of Moscow seemed to shrink to merely eight square meters. It was an unexpected revelation…

Olga stood in the middle of the small, narrow room furnished with a bed, a small table, a chair, a coat rack, and a bookcase. In the corner, a hospital-like bedside table served as a cupboard with a primus stove resting on a metal tray (a thoughtful addition!).

Seeing her hesitation, he wrapped his arm around her and said, «Wife, I honestly warned you that my accommodation is far from ideal. Private rooms in Moscow are extremely rare now, especially in the center. But look, I moved the primus stove here so I wouldn't have to suffer in the communal kitchen.»

Embarrassed that Leonid might perceive her involuntary – not disappointment (as she was no stranger to the hardships of communal living) but rather surprise – Olga explained, «You know, it's just such a contrast…»

«A contrast?» he inquired.

«Yes, exactly. After the vastness of the big city…»

«Ah, I see now!» he breathed a sigh of relief. «It's a thing! Moscow is an intriguing city; you'll be surprised more than once as you get used to it.»

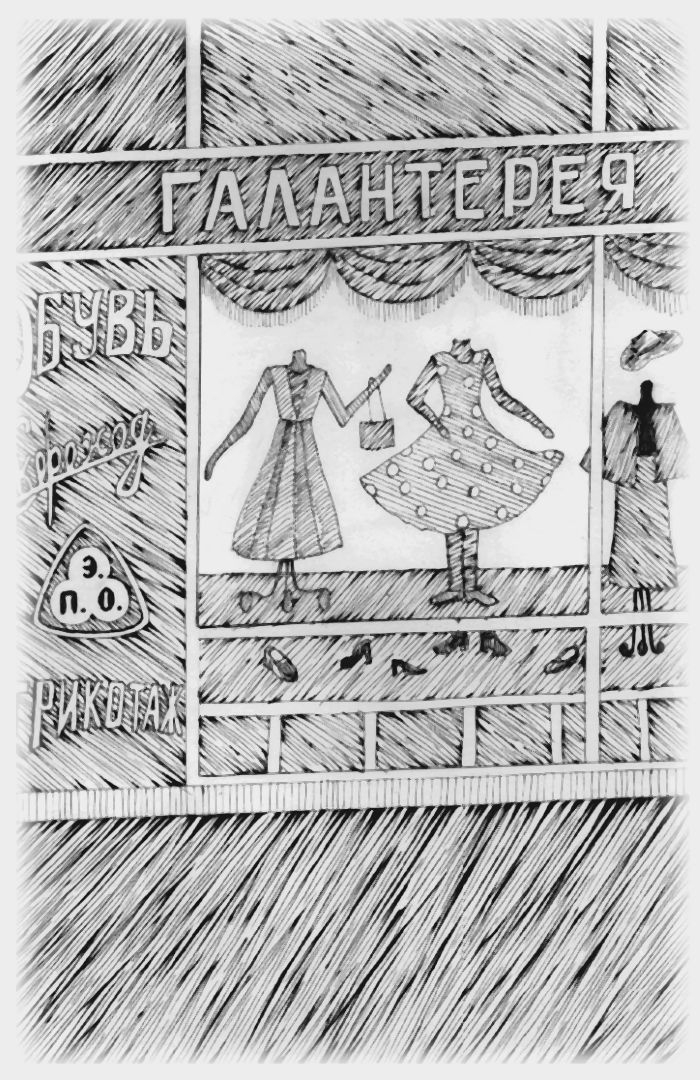

And Olga did get used to it. She quickly learned to navigate a city she had never visited but had only read about. Of course, at first, Leonid took her everywhere: the Patriarch's Ponds (only one of the three still existed), the boulevards, Arbat, Kuznetsky Bridge, Petrovka, Red Square, theaters, and, of course, the stores.

«You need a new dress!» Leonid declared confidently the day after their arrival. «And shoes!»

Mirachevsky still had two years left until graduation, but he couldn't be considered a poor student, thanks to his part-time job as a machinist's assistant, which paid well. Additionally, the NEP (New Economic Policy) allowed him to engage in commerce without fear. Since his days in Kyiv, Mirachevsky had skillfully organized his life and involved his friends in ventures that benefited everyone. In short, the student had some money, though not much. And now, Leonid was doing his best to augment their finances. He bought haberdashery goods from the capital and brought them to Kyiv, and in return, transported sunflower seeds from Ukraine to the capital.

Summer was approaching, and it was time for a vacation. However, there was no honeymoon in sight, so they had to accept it. As he departed, she continued to settle in and soon began to look like a true Muscovite. The streetcars «A» and «B» were almost always crowded, making leisurely walks more appealing. Leonid was right – Olga adored the contrasts of Moscow the most. Turning from the bustling Tverskaya Street onto a boulevard and then into some lane near Arbat, she felt transported back to the last century, expecting to encounter a lady with a dog, adjusting her hat, any moment. Beloved literary works seemed to come to life here, and their characters felt almost tangible.

* * *

Certainly, the reality in the country had evolved significantly, far from the world of classical literature. Party discussions, adopted economic plans, the fight against illiteracy, and the promotion of chemical knowledge under the slogan «Mass protection from gases – the cause of the working people!» now dominated the scene.

The events of the war anxiety in 1927, the crisis in relations with England, the rupture of diplomatic ties, Chamberlain's ultimatum, talks of the inevitability of war, and the revived hopes for the Bolsheviks' downfall passed unnoticed by Olga. An extensive propaganda campaign against the «conspiracy of the world bourgeoisie,» Polish pans, and internal counterrevolution unfolded against the backdrop of food difficulties. Knowledgeable individuals hinted at impending changes and advised exchanging paper money for tsarist gold rubles. However, Leonid remained calm and endeavored to protect his family and home from any potential shocks.

* * *By the fall, it became evident that the Mirachevsky family was expecting a new addition, and Leonid strongly advised against his pregnant wife taking on any work. Thankfully, Olga was handling the pregnancy quite well. There was only one instance when she felt uncomfortable, during a demonstration they attended to celebrate the tenth anniversary of the October Revolution. The students and teachers of MIIT (Russian University of Transport) marched together, and Olga happily joined Leonid's merry group of friends.

Despite the cold and windy weather, and the long wait for the military parade to finish in the square, the atmosphere was filled with excitement. Bravura music and impassioned speeches resounded from loudspeakers, colorful posters and cartoons floated above the crowd, and the promise of a resolute «answer to Chamberlain» (without a doubt!) stirred the patriotic fervor. As they almost jogged across Red Square (for some inexplicable reason, they had to move quickly), Olga suddenly stopped and turned pale.

«Are you feeling sick?» her husband asked, genuinely worried.

«No, no, I just need to sit down for a moment.»

He helped her to the embankment where he took off his coat and laid it on a damp bench.

«Leonid, why?» she inquired.

«Just sit down and get some rest,» he replied.

Her discomfort passed swiftly, and in the following months, it hardly resurfaced.

* * *Yet, at times, Olga felt uneasy in Moscow. Her husband was often away from home (no blame on him – he was studying and preparing for exams, while also working part-time), and her relatives were not nearby. «If only mom were alive…» The euphoria of moving to the capital had waned during pregnancy, replaced by a sense of loneliness. Despite the care and attention from her 23-year-old soon-to-be father of the child, he couldn't always fully grasp her current emotional state. Even though their room frequently hosted gatherings with friends, and on the rare weekends they had together, they invariably joined friends for outings to the movies or theater. Yet, she yearned for more moments of solitude and privacy…

Letters from her beloved sister, Maria, who at that time resided with her children and mother-in-law at the Tikhaya Pustyn station in the neighboring Kaluga Governorate, brought comfort and support to Olga. Wrapped in a cozy blanket, she read her sister's message: «I am worried about you. Though you don't complain, I can sense that your spirits are not as cheerful. Consider my proposal. It might not be proper to say, but Natalya has taken the place of our mother, and she will warmly welcome you here. The surroundings are delightful. Come, and we will have more fun together.»

Leonid noticed her reading and asked, «Why stay indoors? It's so lovely outside, with the scent of spring in the air. Shall we take a walk?» As he observed her carefully, he inquired, «Are you feeling unwell?»

Silently, Olga handed him the letter. He sat beside her on the bed, read through the lines, and embraced his wife. «Honestly, Id hate to see you go,» he admitted. She remained quiet, and he continued, «I know I haven't been giving you enough attention lately… Your Maria is probably right…» He nodded, as if agreeing with certain thoughts. Then, with his characteristic casualness that charmed everyone, he said, «Still, being in the company of experienced mothers will put you at ease. And I won't worry about leaving you alone.»