Полная версия:

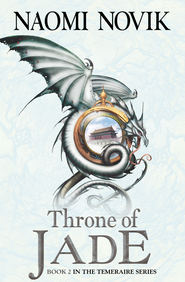

Throne of Jade

Laurence could do little in honesty to reassure him: there was every likelihood he was to be arrested, if Lenton had not managed some miracle of persuasion, and after these multiple offences a court-martial might very well impose a death sentence. Ordinarily an aviator would not be hanged for anything less than outright treason. But Barham would surely have him up before a board of Navy officers, who would be far more severe, and consideration for preserving the dragon’s service would not enter into their deliberations: Temeraire was already lost to England, as a fighting-dragon, by the demands of the Chinese.

It was by no means an easy or a comfortable situation, and still worse was the knowledge that he had imperilled his men; Granby would have to answer for his defiance, and the other lieutenants also, Evans and Ferris and Riggs; any or all of them might be dismissed the service: a terrible fate for an aviator, raised in the ranks from early childhood. Even those midwingmen who never passed for lieutenant were not usually sent away; some work would be found for them, in the breeding grounds or in the coverts, that they might remain in the society of their fellows.

Though his leg had improved some little way overnight, Laurence was still pale and sweating even from the short walk he risked taking up the front stairs of the building. The pain was increasing sharply, dizzying, and he was forced to stop and catch his breath before he went into the small office.

‘Good Heavens; I thought you had been let go by the surgeons. Sit down, Laurence, before you fall down; take this,’ Lenton said, ignoring Barham’s scowl of impatience, and put a glass of brandy into Laurence’s hand.

‘Thank you, sir; you are not mistaken, I have been released,’ Laurence said, and only sipped once for politeness’s sake; his head was already clouded badly enough.

‘That is enough; he is not here to be coddled,’ Barham said. ‘Never in my life have I seen such outrageous behaviour, and from an officer— By God, Laurence, I have never taken pleasure in a hanging, but on this occasion, I would call it good riddance. But Lenton swears to me your beast will become unmanageable; though how we should tell the difference I can hardly say.’

Lenton’s lips tightened at this disdainful tone; Laurence could only imagine the humiliating lengths to which he had been forced in order to impress this understanding on Barham. Though Lenton was an admiral, and fresh from another great victory, even that meant very little in any larger sphere; Barham could offend him with impunity, where any admiral in the Navy would have had political influence and friends enough to require more respectful handling.

‘You are to be dismissed the service, that is beyond question,’ Barham continued. ‘But the animal must be gotten off to China, and for that, I am sorry to say, we require your cooperation. Find some way to persuade him, and we will leave the matter there; any more of this recalcitrance, and I am damned if I will not hang you after all; yes, and have the animal shot, and be damned to those Chinamen also.’

This last very nearly brought Laurence out of his chair, despite his injury; only Lenton’s hand on his shoulder, pressing down firmly, held him in place. ‘Sir, you go too far,’ Lenton said. ‘We have never shot dragons in England for anything less than man-eating, and we are not going to start now; I would have a real mutiny on my hands.’

Barham scowled, and muttered something not quite intelligible under his breath about lack of discipline; which was a fine thing coming from a man who Laurence well knew had served during the great naval mutinies of ’97, when half the fleet had risen up. ‘Well, let us hope it does not come to any such thing. There is a transport in ordinary in harbour at Spithead, the Allegiance; she can be made ready for sea in a week. How then is the animal to be gotten aboard, since he is choosing to be balky?’

Laurence could not bring himself to answer; a week was a horribly short time, and for a moment he even wildly allowed himself to consider the prospect of flight. Temeraire could easily reach the Continent from Dover, and there were places in the forests of the German states where even now feral dragons lived; though only small breeds.

‘It will require some consideration,’ Lenton said. ‘I will not scruple to say, sir, that the whole affair has been mismanaged from the beginning. The dragon has been badly stirred-up, now, and it is no joke to coax a dragon to do something he does not like to begin with.’

‘Enough excuses, Lenton; quite enough,’ Barham began, and then a tapping came on the door; they all looked in surprise as a rather pale-looking midwingman opened the door and said, ‘Sir, sir—’ only to hastily clear out of the way: the Chinese soldiers looked as though they would have trampled straight over him, clearing a path for Prince Yongxing into the room.

They were all of them so startled they forgot at first to rise, and Laurence was still struggling to get up to his feet when Yongxing had already come into the room. The attendants hurried to pull a chair – Lord Barham’s chair – over for the prince; but Yongxing waved it aside, forcing the rest of them to keep on their feet. Lenton unobtrusively put a hand under Laurence’s arm, giving him a little support, but the room still tilted and spun around him, the blaze of Yongxing’s bright-coloured robes stabbing at his eyes.

‘I see this is the way in which you show your respect for the Son of Heaven,’ Yongxing said, addressing Barham. ‘Once again you have thrown Lung Tien Xiang into battle; now you hold secret councils, and plot how you may yet keep the fruits of your thievery.’

Though Barham had been damning the Chinese five minutes before, now he went pale and stammered, ‘Sir, Your Highness, not in the least—’ but Yongxing was not slowed even a little.

‘I have gone through this covert, as you call these animal pens,’ he said. ‘It is not surprising, when one considers your barbaric methods, that Lung Tien Xiang should have formed this misguided attachment. Naturally he does not wish to be separated from the companion who is responsible for what little comfort he has been given.’ He turned to Laurence, and looked him up and down disdainfully. ‘You have taken advantage of his youth and inexperience; but this will not be tolerated. We will hear no further excuses for these delays. Once he has been restored to his home and his proper place, he will soon learn better than to value company so far beneath him.’

‘Your Highness, you are mistaken; we have every intention to cooperate with you,’ Lenton said bluntly, while Barham was still struggling for more polished phrases. ‘But Temeraire will not leave Laurence, and I am sure you know well that a dragon cannot be sent, but only led.’

Yongxing said icily, ‘Then plainly Captain Laurence must come also; or will you now attempt to convince us that he cannot be sent?’

They all stared, in blank confusion; Laurence hardly dared believe he understood properly, and then Barham blurted, ‘Good God, if you want Laurence, you may damn well have him, and welcome.’

The rest of the meeting passed in a haze for Laurence, the tangle of confusion and immense relief leaving him badly distracted. His head still spun, and he answered to remarks somewhat randomly until Lenton finally intervened once more, sending him up to bed. He kept himself awake only long enough to send a quick note to Temeraire by way of the maid, and fell straightaway into a thick, unrefreshing sleep.

He clawed his way out of it the next morning, having slept fourteen hours. Captain Roland was drowsing by his bedside, head tipped against the chair back, mouth open; as he stirred, she woke and rubbed her face, yawning. ‘Well, Laurence, are you awake? You have been giving us all a fright and no mistake. Emily came to me because poor Temeraire was fretting himself to pieces: whyever did you send him such a note?’

Laurence tried desperately to remember what he had written: impossible; it was wholly gone, and he could remember very little of the previous day at all, though the central, the essential point was quite fixed in his mind. ‘Roland, I have not the faintest idea what I said. Does Temeraire know that I am going with him?’

‘Well, now he does, since Lenton told me after I came looking for you, but he certainly did not find it in here,’ she said, and gave him a piece of paper.

It was in his own hand, and with his signature, but wholly unfamiliar, and nonsensical:

Temeraire—

Never fear; I am going; the Son of Heaven will not tolerate delays, and Barham gives me leave. Allegiance will carry us! Pray eat something.

—L.

Laurence stared at it in some distress, wondering how he had come to write so. ‘I do not remember a word of it; but wait, no; Allegiance is the name of the transport, and Prince Yongxing referred to the Emperor as the Son of Heaven, though why I should have repeated such a blasphemous thing I have no idea.’ He handed her the note. ‘My wits must have been wandering. Pray throw it in the fire; and go tell Temeraire that I am quite well now, and will be with him again soon. Can you ring for someone to valet me? I need to dress.’

‘You look as though you ought to stay just where you are,’ Roland said. ‘No: lie quiet a while. There is no great hurry at present, as far as I understand, and I know this fellow Barham wants to speak with you; also Lenton. I will go tell Temeraire you have not died or grown a second head, and have Emily jog back and forth between you if you have messages.’

Laurence yielded to her persuasions; indeed he did not truly feel up to rising, and if Barham wanted to speak with him again, he thought he would need to conserve what strength he had. However, in the event, he was spared: Lenton came alone instead.

‘Well, Laurence, you are in for a hellishly long trip, I am afraid, and I hope you do not have a bad time of it,’ he said, drawing up a chair. ‘My transport ran into a three-day gale going to India, back in the nineties; rain freezing as it fell, so the dragons could not fly above it for some relief. Poor Obversaria was ill the entire time. Nothing less pleasant than a sea-sick dragon, for them or you.’

Laurence had never commanded a dragon transport, but the image was a vivid one. ‘I am glad to say, sir, that Temeraire has never had the slightest difficulty, and indeed he enjoys sea-travel greatly.’

‘We will see how he likes it if you meet a hurricane,’ Lenton said, shaking his head. ‘Not that I expect either of you have any objections, under the circumstances.’

‘No, not in the least,’ Laurence said, heartfelt. He supposed it was merely a jump from frying-pan to fire, but he was grateful enough even for the slower roasting: the journey would last for many months, and there was room for hope: any number of things might happen before they reached China.

Lenton nodded. ‘Well, you are looking moderately ghastly, so let me be brief. I have managed to persuade Barham that the best thing to do is pack you off bag and baggage, in this case your crew; some of your officers would be in for a good bit of unpleasantness, otherwise, and we had best get you on your way before he thinks better of it.’

Yet another relief, scarcely looked-for. ‘Sir,’ Laurence said, ‘I must tell you how deeply indebted I am—’

‘No, nonsense; do not thank me.’ Lenton brushed his sparse grey hair back from his forehead, and abruptly said, ‘I am damned sorry about all this, Laurence. I would have run mad a good deal sooner, in your place; brutally done, all of it.’

Laurence hardly knew what to say; he had not expected anything like sympathy, and he did not feel he deserved it. After a moment, Lenton went on, more briskly. ‘I am sorry not to give you a longer time to recover, but then you will not have much to do aboard ship but rest. Barham has promised them the Allegiance will sail in a week’s time; though from what I gather, he will be hard put to find a captain for her by then.’

‘I thought Cartwright was to have her?’ Laurence asked, some vague memory stirring; he still read the Naval Chronicle, and followed the assignments of ships; Cartwright’s name stuck in his head: they had served together in Goliath, many years before.

‘Yes, when Allegiance was meant to go to Halifax; there is apparently some other ship being built for him there. But they cannot wait for him to finish a two years’ journey to China and back,’ Lenton said. ‘Be that as it may, someone will be found; you must be ready.’

‘You may be sure of it, sir,’ Laurence said. ‘I will be quite well again by then.’

His optimism was perhaps ill-founded; after Lenton had gone, Laurence tried to write a letter and found he could not quite manage it, his head ached too wretchedly. Fortunately, Granby came by an hour later to see him, full of excitement at the prospect of the journey, and contemptuous of the risks he had taken with his own career.

‘As though I could give a cracked egg for such a thing, when that scoundrel was trying to have you hauled away, and pointing guns at Temeraire,’ he said. ‘Pray don’t think of it, and tell me what you would like me to write.’

Laurence gave up trying to counsel him to caution; Granby’s loyalty was as obstinate as his initial dislike had been, if more gratifying. ‘Only a few lines, if you please – to Captain Thomas Riley; tell him we are bound for China in a week’s time, and if he does not mind a transport, he can likely get Allegiance, if only he goes straightaway to the Admiralty: Barham has no one for the ship; but be sure and tell him not to mention my name.’

‘Very good,’ Granby said, scratching away; he did not write a very elegant hand, the letters sprawling wastefully, but it was serviceable enough to read. ‘Do you know him well? We will have to put up with whoever they give us for a long while.’

‘Yes, very well indeed,’ Laurence said. ‘He was my third lieutenant in Belize, and my second in Reliant; he was at Temeraire’s hatching: a fine officer and seaman. We could not hope for better.’

‘I will run it down to the courier myself, and tell him to be sure it arrives,’ Granby promised. ‘What a relief it would be, not to have one of these wretched stiff-necked fellows—’ and there he stopped, embarrassed; it was not so very long ago he had counted Laurence himself a ‘stiff-necked fellow’, after all.

‘Thank you, John,’ Laurence said hastily, sparing him. ‘Although we ought not get our hopes up yet; the Ministry may prefer a more senior man in the role,’ he added, though privately he thought the chances were excellent. Barham would not have an easy time of it, finding someone willing to accept the post.

Impressive though they might be, to the landsman’s eye, a dragon transport was an awkward sort of vessel to command: often enough they sat in port endlessly, awaiting dragon passengers, while the crew dissipated itself in drinking and whoring. Or they might spend months in the middle of the ocean, trying to maintain a single position to serve as a resting point for dragons crossing long distances; like blockade-duty, only worse for lack of society. Little chance of battle or glory, less of prize-money; they were not desirable to any man who could do better.

But the Reliant, so badly dished in the gale after Trafalgar, would be in dry-dock for a long while. Riley, left on shore with no influence to help him to a new ship, virtually no seniority, would be as glad of the opportunity as Laurence would be to have him, and there was every chance Barham would seize on the first fellow who offered.

Laurence spent the next day labouring, with slightly more success, over other necessary letters. His affairs were not prepared for a long journey, much of it far past the limits of the courier circuit. Then too, over the last dreadful weeks he had entirely neglected his personal correspondence, and by now he owed several replies, particularly to his family. After the battle of Dover, his father had grown more tolerant of his new profession; although they still did not write one another directly, at least Laurence was no longer obliged to conceal his correspondence with his mother, and he had for some time now addressed his letters to her openly. His father might very well choose to suspend that privilege again, after this affair, but Laurence hoped he might not hear the particulars of it: fortunately, Barham had nothing to gain from embarrassing Lord Allendale; particularly not now when Wilberforce, their mutual political ally, meant to make another push for abolition in the next session of Parliament.

Laurence dashed off another dozen hasty notes, in a hand not very much like his usual, to other correspondents; most of them were naval men, who would well understand the exigencies of a hasty departure. Despite much abbreviation, the effort took its toll, and by the time Jane Roland came to see him once again, he had nearly prostrated himself once more, and was lying back against the pillows with eyes shut.

‘Yes, I will post them for you, but you are behaving absurdly, Laurence,’ she said, collecting up the letters. ‘A knock on the head can be very nasty, even if you have not cracked your skull. When I had the yellow fever I did not prance about claiming I was well; I lay in bed and took my gruel and possets, and I was back on my feet quicker than any of the other fellows in the West Indies who took it.’

‘Thank you, Jane,’ he said, and did not argue with her; indeed he felt very ill, and he was grateful when she drew the curtains and cast the room into a comfortable dimness.

He briefly came out of sleep some hours later, hearing some commotion outside the door of his room: Roland saying, ‘You are damned well going to leave now, or I will kick you down the hall. What do you mean, sneaking in here to pester him the instant I have gone out?’

‘But I must speak with Captain Laurence; the situation is of the most urgent—’ the protesting voice was unfamiliar, and rather bewildered. ‘I have ridden straight from London—’

‘If it is so urgent, you may go speak to Admiral Lenton,’ Roland said. ‘No; I do not care if you are from the Ministry; you look young enough to be one of my mids, and I do not for an instant believe you have anything to say that cannot wait until morning.’

With this she pulled the door shut behind her, and the rest of the argument was muffled; Laurence drifted again away. But the next morning there was no one to defend him, and scarcely had the maid brought in his breakfast – the threatened gruel and hot-milk posset, and quite unappetizing – than a fresh attempt at invasion was made, this time with more success.

‘I beg your pardon, sir, for forcing myself upon you in this irregular fashion,’ the stranger said, talking rapidly while he dragged up a chair to Laurence’s bedside, uninvited. ‘Pray allow me to explain; I realize the appearance is quite extraordinary—’ He set down the heavy chair and sat down, or rather perched, at the very edge of the seat. ‘My name is Hammond, Arthur Hammond; I have been deputized by the Ministry to accompany you to the court of China.’

Hammond was a surprisingly young man, perhaps twenty years of age, with untidy dark hair and a great intensity of expression that lent his thin, sallow face an illuminated quality. He spoke at first in half-sentences, torn between the forms of apology and his plain eagerness to come to his subject. ‘The absence of an introduction, I beg you will forgive, we have been taken completely, completely by surprise, and Lord Barham has already committed us to the twenty-third as a sailing date. If you would prefer, we may of course press him for some extension—’

This of all things Laurence was eager to avoid, though he was indeed a little astonished by Hammond’s forwardness; hastily he said, ‘No, sir, I am entirely at your service; we cannot delay sailing to exchange formalities, particularly when Prince Yongxing has already been promised that date.’

‘Ah! I am of a similar mind,’ Hammond said, with a great deal of relief; Laurence suspected, looking at his face and measuring his years, that he had only received the appointment due to the lack of time. But Hammond quickly refuted the notion that a willingness to go to China on a moment’s notice was his only qualification. Having settled himself, he drew out a thick sheaf of papers, which had been distending the front of his coat, and began to discourse in great detail and speed upon the prospects of their mission.

Laurence was almost from the first unable to follow him. Hammond unconsciously slipped into stretches of the Chinese language from time to time, when looking down at those of his papers written in that script, and while speaking in English dwelt largely on the subject of the Macartney embassy to China, which had taken place fourteen years prior. Laurence, who had been newly made lieutenant at the time and wholly occupied with naval matters and his own career, had hardly remembered the existence of the mission at all, much less any details.

He did not immediately stop Hammond, however: there was no convenient pause in the flow of his conversation, for one, and for another there was a reassuring quality to the monologue. Hammond spoke with authority beyond his years, an obvious command of his subject, and, still more importantly, without the least hint of the incivility which Laurence had come to expect from Barham and the Ministry. Laurence was grateful enough for any prospect of an ally to willingly listen, even if all he knew of the expedition himself was that Macartney’s ship, the Lion, had been the first Western vessel to chart the Bay of Zhitao.

‘Oh,’ Hammond said, rather disappointed, when at last he realized how thoroughly he had mistaken his audience. ‘Well, I suppose it does not much signify; to put it plainly, the embassy was a dismal failure. Lord Macartney refused to perform their ritual of obeisance before the Emperor, the kowtow, and they took offence. They would not even consider granting us a permanent mission, and he ended by being escorted out of the China Sea by a dozen dragons.’

‘That I do remember,’ Laurence said; indeed he had a vague recollection of discussing the matter among his friends in the gunroom, with some heat at the insult to Britain’s envoy. ‘But surely the kowtow was quite offensive; did they not wish him to grovel on the floor?’

‘We cannot be turning up our noses at foreign customs when we are coming to their country, hat in hand,’ Hammond said, earnestly, leaning forward. ‘You can see yourself, sir, the evil consequences: I am sure that the bad blood from this incident continues to poison our present relationship.’

Laurence frowned; this argument was indeed persuasive, and made some better explanation why Yongxing had come to England so very ready to be offended. ‘Do you think this same quarrel their reason for having offered Bonaparte a Celestial? After so long a time?’

‘I will be quite honest with you, Captain, we have not the least idea,’ Hammond said. ‘Our only comfort, these last fourteen years – a very cornerstone of foreign policy – has been our certainty, our complete certainty, that the Chinese were no more interested in the affairs of Europe than we are in the affairs of the penguins. Now all our foundations have been shaken.’

Chapter Three

The Allegiance was a wallowing behemoth of a ship: just over four hundred feet in length and oddly narrow in proportion, except for the outsize dragondeck that flared out at the front of the ship, stretching from the foremast forward to the bow. Seen from above, she looked very strange, almost fan-shaped. But below the wide lip of the dragondeck, her hull narrowed quickly; the keel was fashioned out of steel rather than elm, and thickly covered with white paint against rust: the long white stripe running down her middle gave her an almost rakish appearance.

To give her the stability which she required to meet storms, she had a draught of more than twenty feet and was too large to come into the harbour proper, but had to be moored to enormous pillars sunk far out in the deep water and her supplies ferried to and fro by smaller vessels: a great lady surrounded by scurrying attendants. This was not the first transport which Laurence and Temeraire had travelled on, but she would be the first true ocean-going one; a poky three-dragon ship running from Gibraltar to Plymouth with barely a few planks in increased width could offer no comparison.