Полная версия:

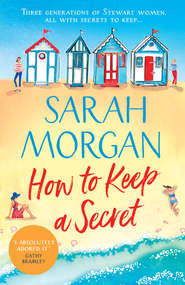

How To Keep A Secret: A fantastic and brilliant feel-good summer read that you won’t want to end!

She walked Andrea back to the school gates, promised to keep an eye on Daisy and then made her way back to the classroom.

The wind was biting and most of the islanders were longing for spring. Not Jenna. Spring meant buds on the trees and lambs playing in the fields. Everywhere you looked there was new life. This time last year she’d been sure that by now she’d be pushing a stroller along the streets. Instead she was back in her classroom teaching other people’s kids.

Of course it was still possible that spring might be lucky for her, too.

If she and Greg had nonstop sex over the next few weeks she could potentially be pregnant by April or May. That would mean a Christmas baby.

She allowed herself a moment of dreaming, and then snapped out of it.

All she thought about was babies.

Obsess: to worry neurotically or obsessively.

Her obsession had even entered the bedroom. When she and Greg made love she found herself thinking, Please let me get pregnant.

Maybe she’d cook a special meal tonight. Open a bottle of wine. Try to relax a little. She could greet him at the door wearing nothing but a smile and hope Mrs. Pardew across the road wasn’t looking out the window.

She reached the door of her classroom and winced at the noise that came from inside.

Bracing herself, she pushed open the door and the noise dimmed to a hum.

“Good morning, Mrs. Sullivan.” The chorus of voices lifted the cloud that had been hanging over her.

Maybe she didn’t have her own children, but she had them. She loved their spontaneity and their innocence, their bright eyes and smiles. She even loved the naughty kids. Like Billy Grant, who was currently standing on his desk, waiting for her reaction.

He was a rebel with a strong sense of adventure and a cavalier attitude to risk. Fortunately no one knew more about that instinct than Jenna.

“Billy, our classroom rule is that we don’t stand on desks.”

Billy folded his arms but didn’t move. “You’re not the boss of me.”

Jenna arched an eyebrow.

He lasted two seconds and then scrambled off the desk and plopped onto his chair.

Everyone knew that when Mrs. Sullivan gave you that look you did what you were supposed to do or you’d be in serious trouble. He made another attempt to deflect blame. “Bradley told me to do it.”

“If he told you to jump off a bridge would you do that?” She straightened her shoulders and addressed the whole class. “One of our classroom rules is that we don’t stand on the desks.”

“Rules are boring,” Bradley muttered. “Why do we have to have them?”

So we can break them.

“Bradley wants to know why we have rules,” she said. “Who can tell him the answer?”

A sea of hands shot into the air and she picked the girl in the front. Little Stacy Adams, whose dad had recently run off with another man, giving the island enough gossip to feast on for a decade.

“To keep us safe.”

“That’s right.” Jenna smiled. “Some rules are there to protect us.” And if you ignored the rules you could be left with a secret and a guilty conscience.

Maybe it was her fault that she wasn’t closer to her mother, she thought. She knew things she wasn’t supposed to know and that made things awkward.

Keeping that thought to herself, she moved to the front of the class. “Everyone sit in a circle.”

There was a mass scramble as they found their places on the floor.

“Will you tell us a story, Mrs. Sullivan?”

“One of your special made-up ones.”

As they sat round watching her expectantly, she felt a rush of pride and affection. Winter would soon give way to spring, and spring to summer and then this group of children would be leaving her classroom for the last time.

When they’d arrived in her class, they’d been a raggedy, unruly bunch but now they were a team. Friendships had formed. Some friendships might even last through to adulthood, as hers and Greg had. Some might fracture.

Not all relationships were easy.

She threw herself into her day, moving from story time to math. Unlike some of her colleagues, she loved teaching first graders. They were curious and enthusiastic. They loved coming to school and they loved her. From the moment she stepped into the classroom, she was wrapped in warmth and affection.

Most of all she enjoyed seeing the progress they made. They experienced so many firsts.

Usually she lingered in the classroom after the children had gone, tidying up and preparing for the following day, but today she drove straight to her mother’s house.

On a cold January day it was foggy and cold and the roads were quiet.

Her mother lived down-island in Edgartown. Ridiculously picturesque with its waterfront and harbor, Edgartown was one of the more populated areas of the island, which was one of the reasons Jenna had chosen to live up-island with its beautiful beaches and spectacular sunsets.

Even in winter when the town was quiet, Jenna preferred the wildness of her part of the island. Her drive took her past rolling farmland, stone fences and beaches. Wherever you were on the Vineyard, you were never far from the beach. And when you couldn’t see the sea, chances were that you could still smell it.

At this time of year she drove easily through Edgartown’s narrow streets.

The Captain’s House where her mother lived was set right on the waterfront, close to the harbor and the lighthouse. The house had been in her family forever, since Captain William Stewart had seen fit to build his home on what was arguably the best plot of land in the whole of Martha’s Vineyard. When her mother’s parents had died in an accident, leaving Nancy an orphan at the age of eight, she’d continued to live in the house with her grandmother.

Money had been tight and they’d rented out rooms to cover their costs.

The house was considered historic, and occasionally Nancy would give a private tour to students or history buffs, and talk about the Vineyard’s place in the whaling industry. Jenna’s father had been heard to say on many an occasion, usually when huddled in his coat in front of a blazing log fire, that because a person was interested in history didn’t mean they wanted to experience it firsthand. The antiquated heating system of The Captain’s House counted as history as far as Tom was concerned. In the middle of winter there had been many nights when Jenna had crawled into bed with her sister for warmth.

Two years previously the heating and wiring had been replaced as part of an upgrade and modernization.

Jenna had wondered at the time why her mother had waited until after her father had died to do it.

The door was open and Jenna walked through the entryway with its wood paneling and wide-planked floor. There were bookshelves stuffed with books, and more books piled next to them on the floor. Every surface was covered in the possessions and purchases of previous generations.

Her mother was a hoarder. Jenna had never seen her throw a single thing away.

There were items in the house that had belonged to her great-grandmother and were never used. Some of those things were ugly, but still Nancy wouldn’t hear of disposing of them.

She considered herself the custodian of the family’s heritage.

Jenna knew that an entire bedroom upstairs was filled with her father’s things. Trophies he’d won playing golf, his model boat collection, his clothes. Did her mother ever go in there? Did she cry over his things?

She found Nancy in the kitchen, opening mail. “Hi, Mom. I made cakes for your book group. Cute, don’t you think?” She removed the lid with a flourish.

“So pretty! Thank you.” Nancy took the tin from her and placed it on the table next to the papers. “How was your day?”

For a wild moment Jenna contemplated telling her the truth.

Not pregnant. Feel crap about it. Any chance of a hug?

She couldn’t remember when her mother had last hugged her.

“My day was fine.” Holding her feelings inside, she walked to the window and stared out across the lawn to the sea. “It’s cold out today. Windy.” Were they really reduced to talking about the weather?

“How’s Greg?”

“He’s great.” She turned. Was it her imagination or was her mother looking older? The lines around her eyes were more pronounced and her hair seemed to have lost its shine.

Jenna had seen photos of her mother as a young woman. Her features were too bold to qualify as pretty, but she’d been striking and had her own individual style. That style seemed to have deserted her years before. Gone were the colorful outfits that had raised eyebrows on the few occasions she’d picked Jenna up from school. These days she dressed mostly in black and navy, as if life had drained the brightness from her.

Nancy signed a letter and slipped it into an envelope. “He’s a special man. It’s good to see you settled and happy, Jenna.”

The comment struck her as odd. It bordered on the personal, and personal was a land her mother rarely visited.

She almost asked if something was wrong, but decided there was no point, so instead they had a neutral conversation about a plan to build affordable housing and the challenges of maintaining the rural character of the island while managing the increase in summer visitors.

“The school is at capacity. We can’t take any more kids without compromising educational standards.” Jenna sat down at the table. It had belonged to her great-grandmother and there were scars and gouges in the wood to prove it. Somewhere underneath Jenna knew she would find her name scratched into the wood.

“Any funny classroom stories for me? I could use some light entertainment.”

Jenna often regaled her with stories, although she’d learned to talk about her day without mentioning anything personal about the kids.

Most of the parents would have been horrified to learn how much their six-year-olds could divulge to their first-grade teacher.

She told her mother about the school trip they had planned to the nature reserve, and about the lesson she’d taught on states of matter where the children had made ice cream in the classroom. The idea had been to demonstrate that a liquid could become a solid, but two of the children had managed to cover themselves in cream.

“And Lily Baker made me a gorgeous card.” She pulled it out of her bag and passed it across the table. “Don’t shake it. It’s heavy on the glitter.”

“She’s back at school?” Her mother slipped her glasses back on so she could look at the card. “I saw her when she was in hospital. Took her a copy of Paint with Nancy and some pencils.”

Back in the day when her mother had been something of a global name in the art world and there had been much demand for her work, someone had suggested producing upmarket educational material—In other words a coloring book, Jenna had said to Lauren—designed to encourage budding artists. The idea was that children would feel they had been given the opportunity to paint with Nancy.

The project had never taken off and boxes of the coloring books had gathered dust in one of the unused rooms in The Captain’s House.

“How did you know Lily was in hospital?”

“Her grandmother is in my book group.”

“Of course. Yes, Lily had a few days in hospital with a fever. Fully recovered, thank goodness.”

They talked for a while and then Jenna went to use the bathroom, but on the way something caught her eye.

“Hey, Mom.” She paused and called out to her mother. “What happened to the painting on this wall?” It was a beautiful seascape, painted by her mother early in her career and one of the few that had never been offered for sale. Her mother’s career as an artist could be divided into two distinct phases. Her earlier work was light and bright and her later work was stormy and dark. Lauren called it her depressing phase. The missing painting was one of her early works, painted before her mother had hit the big time. Jenna loved the wild swirls of blues and greens.

Surely her mother hadn’t sold it?

Her mother emerged from the kitchen. “I—” She stared at the faded space on the wall as if she’d forgotten about it. “I took it down. I thought I might…redecorate.”

“Do you want help? I could come over on the weekend.”

Her mother didn’t hide her alarm. “I don’t think so. I still remember the mess you made of the rug when you decided to paint Lauren’s room bright blue. I came back from a day at the studio and spent the next two days painting my own house instead of a canvas.”

Jenna remembered that incident, too.

Lauren had redecorated her bedroom at least once every three months. Any money she had, she’d spent on interior design magazines. She’d study them, and then use the ideas she liked best, enlisting Jenna to help transform her room to match her latest vision. They’d dragged furniture from one side of the room to another, painted walls and changed fabrics.

On one occasion Jenna, as dreamy as she was clumsy, had tripped over a tin of blue paint and sent it flowing over the floor.

With her usual artistic flourish, their mother had turned the streaked floor into a smooth surface of ocean blue. Then she’d diluted the color for the walls until the room looked like an aquarium complete with small fish and plants.

Jenna had loved the newly painted room so much she’d taken to sneaking in and sleeping on Lauren’s floor, settling herself between a friendly-looking octopus and a seahorse. She and Lauren had giggled and talked long into the night cocooned in their underwater paradise and when her sister had changed her room three months later, Jenna had felt bereft.

It was at least twenty years since the paint spill episode and yet her mother still talked about it as if it had happened yesterday.

“I’ve improved since then,” Jenna said. “I did most of the decorating in my house.” But her mother had already walked back into the kitchen and wasn’t listening.

Irritated, Jenna used the bathroom and walked back to the kitchen.

Her mother was staring at another set of papers but she quickly pushed them to one side.

“Have you spoken to your sister lately?”

“Last week. I thought I might call tonight, but then I remembered it’s Ed’s fortieth birthday party. She’s booked caterers and a string quartet.” Jenna tried to read the papers, but they were upside down. “If she still lived on island I could have loaned her my recorder group. That would have blown everyone’s eardrums.” She realized her mother wasn’t listening. “Mom?”

Her mother gave a start. “Sorry? What did you say?”

“I was talking about Lauren’s party. She was nervous something might go wrong.”

“Knowing Lauren, it will be perfect. I don’t know how she does it all.”

Jenna refrained from pointing out that Ed was seriously wealthy and that they could buy in whatever help they needed.

For the past couple of years Lauren had been studying for an interior design qualification, but study was a bed of roses compared with hauling yourself out of bed every day to deal with a bunch of kids with runny noses.

Her sister’s life seemed effortless.

“Mack has big exams this summer.”

“She’ll fly through them, as Lauren did.”

“I guess she will.” Did her sister have to be so perfect? Much as she loved Lauren, there were days when Jenna could happily kill her. And then she felt guilty feeling that way because as well as being perfect at everything else, Lauren was the perfect sister and always had been.

It wasn’t Lauren’s fault that her sister couldn’t get pregnant.

Feeling empty, Jenna reached for the tin on the table. The book group wasn’t going to miss one cake, were they?

She fought an internal battle between want and willpower.

Willpower might have won, but as she went to pull her hand back her mother frowned.

“Are you sure you need that?”

No, she didn’t need it. But she wanted it. And dammit if she wanted it, she was going to have it. She was thirty-two years old. She didn’t need her mother’s permission to eat.

She took a cake from the tin, so annoyed she took a bigger bite than she intended to. Too big. Damn. Her teeth were jammed together so now she couldn’t even speak. Instead she chewed slowly, feeling like a python that had swallowed its prey whole.

Her mother went back to sorting papers. “Mack is doing well. Like Lauren, she is very disciplined.”

The implication being that she, Jenna, showed no self-discipline at all.

She swallowed.

Finally. In the battle of woman against cupcake she was the victor.

“Good to know.”

“Lauren is lucky Mack hasn’t turned out to be a wild child like—” her mother waved her hand vaguely “—some people.”

“You mean me.” Jenna kept her tone light. “Thanks, Mom.”

“You have to admit you didn’t sit round waiting for trouble to find you. You went out looking for it and you dragged your poor sister into it with you. You, Jenna Elizabeth Stewart, were enough to give any mother gray hairs.”

“I’ve been Sullivan for more than a decade, Mom.”

“I know.” Nancy’s expression softened. “And you are lucky to have that man.”

Annoyed: irritated or displeased.

“He’s lucky to have me, too.”

“I know. But let’s be honest—you stopped getting into trouble the day you married Greg.” She glanced at the clock. “It will be dark soon. You should probably leave.”

“I can drive in the dark, Mom. There’s this amazing invention called headlights.”

“I don’t like you driving in the dark. Remember when you drove the car into the ditch?”

She did remember, but even smashing her head against the windshield hadn’t been as uncomfortable as this stroll down memory lane. “I was twenty-one. My driving has improved since then.” Jenna stood up. “But you’re right. I should go. I need to stop at the store to pick up some things for dinner. Take care, Mom. Enjoy your book group.”

“I will. Thanks for dropping by.”

As if she was a stranger, not family.

There were days when Jenna wondered whether the only way to get closer to her mother was to join the book group.

CHAPTER FOUR

Nancy

Secret: a fact that is known by only a small number of people, and is not told to anyone else

AS SOON AS the door slammed behind her daughter, Nancy grabbed her coat.

She’d been so desperate for Jenna to leave, she’d almost bundled her out of the house.

Pushing her arms into the sleeves, she stepped into the garden.

At this time of year it looked sad and tired. Maintaining a coastal garden was always a challenge, and this one was particularly exposed.

The narrow strip of windswept land was all that separated The Captain’s House from the sea. She’d seen this view in every season and every mood. Today the surface of the water was smooth, almost glass-like, but she knew it could change in a moment from deceptive calm to boiling anger. Her seafaring ancestors would have told her that you should never trust the sea.

Like humans, she thought. You shouldn’t trust them either.

It was trust that had led her to this moment. The moment she’d been dreading.

She’d let everyone down.

She could refuse to answer the door of course. Pretend not to be home. But what would that achieve? It would only postpone the inevitable. And she’d been the one to call him, so not opening the door would be ridiculous.

She’d been terrified he might arrive while Jenna was here, but fortunately she hadn’t stayed long and hadn’t seemed to notice that Nancy was almost urging her out of the house.

It was one of the few occasions she’d been relieved not to have a particularly close relationship with her daughters.

Nancy would have to tell her the truth eventually, of course, but not yet.

The worse part was the waiting, and yet the ability to wait should have been in her genes. Her great-great-grandmother might have stood in this exact same spot two centuries before while waiting for her husband to return home after two long years at sea. What must she have imagined, thinking of the tall square-rigged ships out there facing mountainous seas and Arctic ice? And how must the captain himself have felt finally returning home after years of battling the elements?

He would have seen the house he’d built and felt pride.

Nancy’s cheeks were ice-cold and she realized she was crying. When had she last cried? She couldn’t remember. It was as if the relentless wind blowing off the sea had eroded her tough outer layer and exposed all her vulnerabilities. She was crumbling and she wasn’t sure she had the strength to handle what was coming next.

At some point over the past sixty-seven years she was supposed to have accumulated knowledge and wisdom, but right now she felt like a small child, lost and alone. Dread was a lurch in the pit of your stomach, a cold chill on your skin. It was the ground shifting beneath your feet like the deck of a ship in a squall until you wanted to cling to something to steady yourself.

She closed her hand round the wood of the Adirondack chair that had been a birthday gift from her daughters. In the spring and summer months she sat out here with her morning coffee, watching the boats, the gulls and the swell of the tide.

Now, on a cold January afternoon with the dark closing in, it was too cold for sitting. Already her hands were chilled, the tips of her fingers numb. She should have worn gloves but she’d only intended to step outside for a moment. One breath of air to hopefully trigger a burst of inspiration that had so far eluded her.

She desperately wanted someone to tell her what to do. Someone to hold her and tell her everything was going to be all right.

Pathetic.

There was no one. The responsibility was hers.

“Nancy!”

Nancy saw her neighbor Alice easing her bulk through the garden gate. Two bad hips and a love of doughnuts had added enough padding to her small frame to make walking even short distances a challenge.

They’d been neighbors their whole lives and friends for almost as long.

Alice was breathless by the time she crossed the lawn to where Nancy was standing.

“I saw Jenna’s car. Does that mean you told her?”

“No.”

“Lord above, what did the two of you talk about for an hour?” Alice slipped her arm through Nancy’s, as she’d always done when they used to walk to school together.

Nancy wanted to pull away. She’d thought she wanted support, but now she realized she didn’t.

“I don’t know. Sometimes I wonder how it’s possible to talk for an hour and say nothing.”

“You’ll have to tell her eventually. Our children think we don’t have lives, that’s the trouble. All my Marion talks about are the children. Does she think nothing happens in my life? My Rosa rugosas may not interest her, but they’re important to me.”

Nancy and Alice shared a love of gardening. Before Nancy had employed Ben, the two women had helped each other in the garden and shared knowledge on which plants could withstand the harsh island weather and sea spray.

“I wasn’t there for my girls,” she said, “so how can I ask them to be there for me?”

“Nancy Lilian Stewart, would you listen to yourself? When you say things like that after all the sacrifices you made, I swear I want to slap you. You should tell them everything.”

Everything?

Even Alice didn’t know everything. “It’s too late to change the way things are.”

“That’s nonsense.”

“I feel like a failure.”

“You give it all you’ve got. What you’ve got isn’t enough, that’s all. Not because you’re a failure, but because life can deliver blows that would fell a mountain.”

They stood side by side in silence.