Полная версия

Полная версияPlays: Lady Frederick, The Explorer, A Man of Honour

Somebody told me you'd gone abroad. Was it you, Dick? Dick is an admirable person, a sort of gazetteer for polite society.

DickWon't you have some tea, Lucy?

LucyNo, thanks!

Mrs. Crowley[Trying on her side also to make conversation.] We shall miss you dreadfully when you're gone, Mr. Mackenzie.

Dick[Cheerfully.] Not a bit of it.

Alec[Smiling.] London is an excellent place for showing one of how little importance one is in the world. One makes a certain figure, and perhaps is tempted to think oneself of some consequence. Then one goes away, and on returning is surprised to discover that nobody has even noticed one's absence.

DickYou're over-modest, Alec. If you weren't, you might be a great man. Now, I make a point of telling my friends that I'm indispensable, and they take me at my word.

AlecYou are a leaven of flippancy in the heavy dough of British righteousness.

DickThe wise man only takes the unimportant quite seriously.

Alec[With a smile.] For it is obvious that it needs more brains to do nothing than to be a cabinet minister.

DickYou pay me a great compliment, Alec. You repeat to my very face one of my favourite observations.

Lucy[Almost in a whisper.] Haven't I heard you say that only the impossible is worth doing?

AlecGood heavens, I must have been reading the headings of a copy-book.

Mrs. Crowley[To Dick.] Are you going to Southampton to see Mr. Mackenzie off?

DickI shall hide my face on his shoulder and weep salt tears. It'll be most affecting, because in moments of emotion I always burst into epigram.

AlecI loathe all solemn leave-takings. I prefer to part from people with a nod and a smile, whether I'm going for ever or for a day to Brighton.

Mrs. CrowleyYou're very hard.

AlecDick has been teaching me to take life flippantly. And I have learnt that things are only serious if you take them seriously, and that is desperately stupid. [To Lucy.] Don't you agree with me?

LucyNo.

[Her tone, almost tragic, makes him pause for an instant; but he is determined that the conversation shall be purely conventional.AlecIt's so difficult to be serious without being absurd. That is the chief power of women, that life and death are merely occasions for a change of costume: marriage a creation in white, and the worship of God an opportunity for a Paris bonnet.

[Mrs. Crowley makes up her mind to force a crisis, and she gets up.Mrs. CrowleyIt's growing late, Dick. Won't you take me round the house?

AlecI'm afraid my luggage has made everything very disorderly.

Mrs. CrowleyIt doesn't matter. Come, Dick!

Dick[To Lucy.] You don't mind if we leave you?

LucyOh, no.

[Mrs. Crowley and Dick go out. There is a moment's silence.AlecDo you know that our friend Dick has offered his hand and heart to Mrs. Crowley this afternoon?

LucyI hope they'll be very happy. They're very much in love with one another.

Alec[Bitterly.] And is that a reason for marrying? Surely love is the worst possible foundation for marriage. Love creates illusions, and marriages destroy them. True lovers should never marry.

LucyWill you open the window? It seems stifling here.

AlecCertainly. [From the window.] You can't think what a joy it is to look upon London for the last time. I'm so thankful to get away.

[Lucy gives a little sob and Alec turns to the window. He wants to wound her and yet cannot bear to see her suffer.AlecTo-morrow at this time I shall be well started. Oh, I long for that infinite surface of the clean and comfortable sea.

LucyAre you very glad to go?

Alec[Turning to her.] I feel quite boyish at the very thought.

LucyAnd is there no one you regret to leave?

AlecYou see, Dick is going to marry. When a man does that, his bachelor friends are wise to depart gracefully before he shows them that he needs their company no longer. I have no relations and few friends. I can't flatter myself that any one will be much distressed at my departure.

Lucy[In a low voice.] You must have no heart at all.

Alec[Icily.] If I had, I certainly should not bring it to Portman Square. That sentimental organ would be surely out of place in such a neighbourhood.

Lucy[Gets up and goes to him.] Oh, why do you treat me as if we were strangers? How can you be so cruel?

Alec[Gravely.] Don't you think that flippancy is the best refuge from an uncomfortable position. We should really be much wiser merely to discuss the weather.

Lucy[Insisting.] Are you angry because I came?

AlecThat would be ungracious on my part. Perhaps it wasn't quite necessary that we should meet again.

LucyYou've been acting all the time I've been here. D'you think I didn't see it was unreal when you talked with such cynical indifference. I know you well enough to tell when you're hiding your real self behind a mask.

AlecIf I'm doing that, the inference is obvious that I wish my real self to be hidden.

LucyI would rather you cursed me than treat me with such cold politeness.

AlecI'm afraid you're rather difficult to please.

[Lucy goes up to him passionately, but he draws back so that she may not touch him.LucyOh, you're of iron. Alec, Alec, I couldn't let you go without seeing you once more. Even you would be satisfied if you knew what bitter anguish I've suffered. Even you would pity me. I don't want you to think too badly of me.

AlecDoes it much matter what I think? We shall be so many thousand miles apart.

LucyI suppose that you utterly despise me.

AlecNo. I loved you far too much ever to do that. Believe me, I only wish you well. Now that the bitterness is past, I see that you did the only possible thing. I hope that you'll be very happy.

LucyOh, Alec, don't be utterly pitiless. Don't leave me without a single word of kindness.

AlecNothing is changed, Lucy. You sent me away on account of your brother's death.

[There is a long silence, and when she speaks it is hesitatingly, as if the words were painful to utter.LucyI hated you then, and yet I couldn't crush the love that was in my heart. I used to try and drive you away from my thoughts, but every word you had ever said came back to me. Don't you remember? You told me that everything you did was for my sake. Those words hammered at my heart as though it were an anvil. I struggled not to believe them. I said to myself that you had sacrificed George coldly, callously, prudently, but in my heart I knew it wasn't true. [He looks at her, hardly able to believe what she is going to say, but does not speak.] Your whole life stood on one side and only this hateful story on the other. You couldn't have grown into a different man in one single instant. I came here to-day to tell you that I don't understand the reason of what you did. I don't want to understand. I believe in you now with all my strength. I know that whatever you did was right and just – because you did it.

[He gives a long, deep sigh.AlecThank God! Oh, I'm so grateful to you for that.

LucyHaven't you anything more to say to me than that?

AlecYou see, it comes too late. Nothing much matters now, for to-morrow I go away.

LucyBut you'll come back.

AlecI'm going to a part of Africa from which Europeans seldom return.

Lucy[With a sudden outburst of passion.] Oh, that's too horrible. Don't go, dearest! I can't bear it!

AlecI must now. Everything is settled, and there can be no drawing back.

LucyDon't you care for me any more?

AlecCare for you? I love you with all my heart and soul.

Lucy[Eagerly.] Then take me with you.

AlecYou!

LucyYou don't know what I can do. With you to help me I can be brave. Let me come, Alec?

AlecNo, it's impossible. You don't know what you ask.

LucyThen let me wait for you? Let me wait till you come back?

AlecAnd if I never come back?

LucyI will wait for you still.

AlecThen have no fear. I will come back. My journey was only dangerous because I wanted to die. I want to live now, and I shall live.

LucyOh, Alec, Alec, I'm so glad you love me.

THE ENDA MAN OF HONOUR

…For Clisthenes, son of Aristonymus, son of Myron, son of Andreas, had a daughter whose name was Agarista: her he resolved to give in marriage to the man whom he should find the most accomplished of all the Greeks. When therefore the Olympian games were being celebrated, Clisthenes, being victorious in them in the chariot race, made a proclamation; "that whoever of the Greeks deemed himself worthy to become the son-in-law of Clisthenes, should come to Sicyon on the sixtieth day, or even before; since Clisthenes had determined on the marriage in a year, reckoning from the sixtieth day." Thereupon such of the Greeks as were puffed up with themselves and their country, came as suitors; and Clisthenes, having made a race-course and palæstra for them, kept it for this very purpose. From Italy, accordingly, came Smindyrides, son of Hippocrates, a Sybarite, who more than any other man reached the highest pitch of luxury, (and Sybaris was at that time in a most flourishing condition;) and Damasus of Siris, son of Amyris called the Wise: these came from Italy. From the Ionian gulf, Amphimnestus, son of Epistrophus, an Epidamnian; he came from the Ionian gulf. An Ætolian came, Males, brother of that Titormus who surpassed the Greeks in strength, and fled from the society of men to the extremity of the Ætolian territory. And from Peloponnesus, Leocedes, son of Pheidon, tyrant of the Argives, a decendant of that Pheidon, who introduced measures among the Peloponnesians, and was the most insolent of all the Greeks, who having removed the Elean umpires, himself regulated the games at Olympia; his son accordingly came. And Amiantus, son of Lycurgus, an Arcadian from Trapezus; and an Azenian from the city of Pæos, Laphanes, son of Euphorion, who, as the story is told in Arcadia, received the Dioscuri in his house, and after that entertained all men; and an Elean, Onomastus, son of Agæus: these accordingly came from the Peloponnesus itself. From Athens there came Megacles, son of Alcmæon, the same who had visited Crœsus, and another, Hippoclides, son of Tisander, who surpassed the Athenians in wealth and beauty. From Eretria, which was flourishing at that time, came Lysanias; he was the only one from Eubœa. And from Thessaly there came, of the Scopades, Diactorides a Cranonian; and from the Molossi, Alcon. So many were the suitors. When they had arrived on the appointed day, Clisthenes made inquiries of their country, and the family of each; then detaining them for a year, he made trial of their manly qualities, their dispositions, learning, and morals; holding familiar intercourse with each separately, and with all together, and leading out to the gymnasia such of them as were younger; but most of all he made trial of them at the banquet; for as long as he detained them, he did this throughout, and at the same time entertained them magnificently. And somehow of all the suitors those that had come from Athens pleased him most, and of these Hippoclides, son of Tisander, was preferred both on account of his manly qualities, and because he was distantly related to the Cypselidæ in Corinth. When the day appointed for the consummation of the marriage arrived, and for the declaration of Clisthenes himself, whom he would choose of them all, Clisthenes, having sacrificed a hundred oxen, entertained both the suitors themselves and all the Sicyonians; and when they had concluded the feast, the suitors had a contest about music, and any subject proposed for conversation. As the drinking went on, Hippoclides, who much attracted the attention of the rest, ordered the flute-player to play a dance; and when the flute-player obeyed, he began to dance: and he danced, probably so as to please himself; but Clisthenes, seeing it, beheld the whole matter with suspicion. Afterwards, Hippoclides, having rested awhile, ordered some one to bring in a table; and when the table came in, he first danced Laconian figures on it, and then Attic ones; and in the third place, having leant his head on the table he gesticulated with his legs. But Clisthenes, when he danced the first and second time, revolted from the thought of having Hippoclides for his son-in-law, on account of his dancing and want of decorum, yet restrained himself, not wishing to burst out against him; but when he saw him gesticulating with his legs, he was no longer able to restrain himself, and said: "Son of Tisander, you have danced away your marriage." But Hippoclides answered: "Hippoclides cares not." Hence this answer became a proverb. (Herodotus VI. 126, Cary's Translation.)

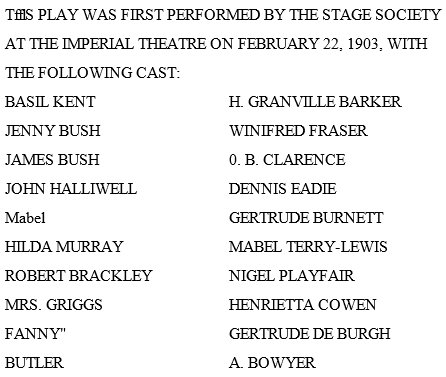

Basil Kent

Jenny Bush

James Bush

John Halliwell

Mabel

Hilda Murray

Robert Brackley

Mrs. Griggs

Fanny

Butler

Time: The Present DayAct I —Basil's lodgings in Bloomsbury.

Acts II and IV —The drawing-room of Basil's house at Putney.

Act III —Mrs. Murray's house in Charles Street.

The Performing Rights of this Play are fully protected, and permission to perform it, whether by Amateurs or Professionals, must be obtained in advance from the author's Sole Agent, R. Golding Bright, 20 Green Street, Leicester Square, London, W.C., from whom all particulars can be obtainedTHE FIRST ACT

Sitting-room of Basil's Lodgings in Bloomsbury.

In the wall facing the auditorium, two windows with little iron balconies, giving a view of London roofs. Between the windows, against the wall, is a writing-desk littered with papers and books. On the right is a door, leading into the passage; on the left a fire-place with arm-chairs on either side; on the chimney-piece various smoking utensils. There are numerous bookshelves filled with books; while on the walls are one or two Delft plates, etchings after Rossetti, autotypes of paintings by Fra Angelico and Botticelli. The furniture is simple and inexpensive, but there is nothing ugly in the room. It is the dwelling-place of a person who reads a great deal and takes pleasure in beautiful things.

Basil Kent is leaning back in his chair, with his feet on the writing-table, smoking a pipe and cutting the pages of a book. He is a very good-looking man of six-and-twenty, clean-shaven, with a delicate face and clear-cut features. He is dressed in a lounge-suit.

[There is a knock at the door.BasilCome in.

Mrs. GriggsDid you ring, sir?

BasilYes. I expect a lady to tea. And there's a cake that I bought on my way in.

Mrs. GriggsVery well, sir.

[She goes out, and immediately comes in with a tray on which are two cups, sugar, milk, &c.BasilOh, Mrs. Griggs, I want to give up these rooms this day week. I'm going to be married. I'm sorry to leave you. You've made me very comfortable.

Mrs. Griggs[With a sigh of resignation.] Ah, well, sir, that's lodgers all over. If they're gents they get married; and if they're ladies they ain't respectable.

[A ring is heard.BasilThere's the bell, Mrs. Griggs. I dare say it's the lady I expect. If any one else comes, I'm not at home.

Mrs. GriggsVery well, sir.

[She goes out, and Basil occupies himself for a moment in putting things in order. Mrs. Griggs, opening the door, ushers in the new-comers.Mrs. GriggsIf you please, sir.

[She goes out again, and during the next few speeches brings two more cups and the tea.[Mabel and Hilda enter, followed by John Halliwell. Basil going towards them very cordially, half stops when he notices who they are; and a slight expression of embarrassment passes over his face. But he immediately recovers himself and isextremely gracious. Hilda Murray is a tall, handsome woman, self-possessed and admirably gowned. Mabel Halliwell is smaller, pretty rather than beautiful, younger than her sister, vivacious, very talkative, and somewhat irresponsible. John is of the same age as Basil, good-humoured, neither handsome nor plain blunt of speech and open.Basil[Shaking hands.] How d'you do?

MabelLook pleased to see us, Mr. Kent.

BasilI'm perfectly enchanted.

HildaYou did ask us to come and have tea with you, didn't you?

BasilI've asked you fifty times. Hulloa, John! I didn't see you.

JohnI'm the discreet husband, I keep in the background.

MabelWhy don't you praise me instead of praising yourself? People would think it so much nicer.

JohnOn the contrary, they'd be convinced that when we were alone I beat you. Besides, I couldn't honestly say that you kept in the background.

Hilda[To Basil.] I feel rather ashamed at taking you unawares.

BasilI was only slacking. I was cutting a book.

MabelThat's ever so much more fun than reading it, isn't it? [She catches sight of the tea things.] Oh, what a beautiful cake – and two cups! [She looks at him, questioning.]

Basil[A little awkwardly.] Oh – I always have an extra cup in case some one turns up, you know.

MabelHow unselfish! And do you always have such expensive cake?

Hilda[With a smile, remonstrating.] Mabel!

MabelOh, but I know them well, and I love them dearly. They cost two shillings at the Army and Navy Stores, but I can't afford them myself.

JohnI wish you'd explain why we've come, or Basil will think I'm responsible.

Mabel[Lightly.] I've been trying to remember ever since we arrived. You say it, Hilda; you invented it.

Hilda[With a laugh.] Mabel, I'll never take you out again. They're perfectly incorrigible, Mr. Kent.

Basil[To John and Mabel, smiling.] I don't know why you've come. Mrs. Murry has promised to come and have tea with me for ages.

Mabel[Pretending to feel injured.] Well, you needn't turn me out the moment we arrive. Besides, I refuse to go till I've had a piece of that cake.

BasilWell, here's the tea! [Mrs. Griggs brings it in as he speaks. He turns to Hilda.] I wish you'd pour it out. I'm so clumsy.

Hilda[Smiling at him affectionately.] I shall be delighted.

[She proceeds to do so, and the conversation goes on while Basil hands Mabel tea and cake.JohnI told them it was improper for more than one woman at a time to call at a bachelor's rooms, Basil.

BasilIf you'd warned me I'd have made the show a bit tidier.

MabelOh, that's just what we didn't want. We wanted to see the Celebrity at Home, without lime-light.

Basil[Ironically.] You're too flattering.

MabelBy the way, how is the book?

BasilQuite well, thanks.

MabelI always forget to ask how it's getting on.

BasilOn the contrary, you never let slip an opportunity of making kind inquiries.

MabelI don't believe you've written a word of it.

HildaNonsense, Mabel. I've read it.

MabelOh, but you're such a monster of discretion… Now I want to see your medals, Mr. Kent.

Basil[Smiling.] What medals?

MabelDon't be coy! You know I mean the medals they gave you for going to the Cape.

Basil[Gets them from a drawer, and with a smile hands them to Mabel.] If you really care to see them, here they are.

Mabel[Taking one.] What's this?

BasilOh, that's just the common or garden South African medal.

MabelAnd the other one?

BasilThat's the D.S.M.

MabelWhy didn't they give you the D.S.O.?

BasilOh, I was only a trooper, you know. They only give the D.S.O. to officers.

MabelAnd what did you do to deserve it?

Basil[Smiling.] I really forget.

HildaIt's given for distinguished service in the field, Mabel.

MabelI knew. Only I wanted to see if Mr. Kent was modest or vain.

Basil[With a smile, taking the medals from her and putting them away.] How spiteful of you!

MabelJohn, why didn't you go to the Cape, and do heroic things?

JohnI confined my heroism to the British Isles. I married you, my angel.

MabelIs that funny or vulgar?

Basil[Laughing.] Are there no more questions you want to ask me, Mrs. Halliwell?

MabelYes, I want to know why you live up six flights of stairs.

Basil[Amused.] For the view, simply and solely.

MabelBut, good heavens, there is no view. There are only chimney-pots.

BasilBut they're most æsthetic chimney-pots. Do come and look, Mrs. Murray. [Basil and Hilda approach one of the windows, and he opens it.] And at night they're so mysterious. They look just like strange goblins playing on the house-tops. And you can't think how gorgeous the sunsets are: sometimes, after the rain, the slate roofs glitter like burnished gold. [To Hilda.] Often I think I couldn't have lived without my view, it says such wonderful things to me. [Turning to Mabel gaily.] Scoff, Mrs. Halliwell, I'm on the verge of being sentimental.

MabelI was wondering if you'd made that up on the spur of the moment, or if you'd fished it out of an old note-book.

Hilda[With a look at Basil.] May I go out?

BasilYes, do come.

[Hilda and Basil step out on the balcony, whereupon John goes to Mabel and tries to steal a kiss from her.Mabel[Springing up.] Go away, you horror!

JohnDon't be silly. I shall kiss you if I want to.

[She laughing, walks round the sofa while he pursues her.

MabelI wish you'd treat life more seriously.

JohnI wish you wouldn't wear such prominent hats.

Mabel[As he puts his arm round her waist.] John, some body'll see us.

JohnMabel, I command you to let yourself be kissed.

MabelHow much will you give me?

JohnSixpence.

Mabel[Slipping away from him.] I can't do it for less than half-a-crown.

John[Laughing.] I'll give you two shillings.

Mabel[Coaxing.] Make it two-and-three.

[He kisses her.JohnNow come and sit down quietly.

Mabel[Sitting down by his side.] John, you mustn't make love to me. It would look so odd if they came in.

JohnAfter all, I am your husband.

MabelThat's just it. If you wanted to make love to me you ought to have married somebody else. [He puts his arm round her waist.] John, don't, I'm sure they'll come in.

JohnI don't care if they do.

Mabel[Sighing.] John, you do love me?

JohnYes.

MabelAnd you won't ever care for anybody else?

JohnNo.

Mabel[In the same tone.] And you will give me that two-and-threepence, won't you?

JohnMabel, it was only two shillings.

MabelOh, you cheat!

John[Getting up.] I'm going out on the balcony. I'm passionately devoted to chimney-pots.

MabelNo, John, I want you.

JohnWhy?

MabelIsn't it enough for me to say I want you for you to hurl yourself at my feet immediately?

JohnOh, you poor thing, can't you do without me for two minutes?

MabelNow you're taking a mean advantage. It's only this particular two minutes that I want you. Come and sit by me like a nice, dear boy.

JohnNow what have you been doing that you shouldn't?

Mabel[Laughing.] Nothing. But I want you to do something for me.

JohnHa, ha! I thought so.

MabelIt's merely to tie up my shoe. [She puts out her foot.]

JohnIs that all – honour bright?

Mabel[Laughing.] Yes. [John kneels down.]

JohnBut, my good girl, it's not undone.

MabelThen, my good boy, undo it and do it up again.

John[Starting up.] Mabel, are we playing gooseberry – at our time of life?

Mabel[Ironically.] Oh, you are clever! Do you think Hilda would have climbed six flights of stairs unless Love had lent her wings?

JohnI wish Love would provide wings for the chaperons as well.