Полная версия:

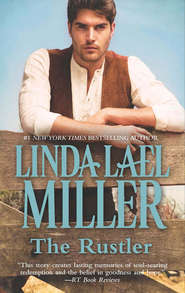

The Rustler

A month ago, he’d wound up in Tucson, and there was a letter waiting from Rowdy, full of news about Lark and the baby and his job in Stone Creek. He’d related the story of Pappy’s death, and said if Wyatt wanted honest work, a friend of his named Sam O’Ballivan was always looking for cowpokes.

At the time, Wyatt had regarded that letter as a fluke of the postal system.

Now, he figured Rowdy must have figured he’d wind up in the Arizona Territory eventually, maybe looking for Pappy, and wished he’d never set foot in the post office in Tucson. Or, better yet, thrown in with the likes of Billy Justice before Rowdy offered him a fresh start.

“I can’t stay, Rowdy,” he said.

“You’ll stay,” Rowdy said.

“What makes you so damn sure?”

“That old nag of yours is practically dead on his feet. He doesn’t have another long ride in him.”

“He made it here, didn’t he?”

Rowdy didn’t seem to be listening. “I’ve got a spare gelding out there in the barn. You can ride him if you see the need. Name’s Sugarfoot, and he’ll throw you if you try to mount up on the right side.”

“When it comes to riding out, one horse is as good as another,” Wyatt said, but he was thinking of old Reb, the paint gelding, and how sorry he’d be to leave him behind. They’d been partners since that turn of the cards in Abilene, after all, and Wyatt would have been in a fine fix without him.

“You’re a lot of things, Wyatt,” Rowdy reasoned, “but a horse thief isn’t among them. Especially when the horse in question belongs to me.”

Wyatt scowled, said nothing. He was fresh out of arguments, at the moment. Hadn’t kept up on his arguing skills, the way Rowdy had.

Rowdy saw his advantage and pressed it. “And then there’s Sarah Tamlin,” he said.

“What about Sarah Tamlin?” Lark asked, appearing in the bedroom doorway with a fat satchel in one hand.

Wyatt glared at Rowdy.

Rowdy merely grinned.

“She smokes cigars,” Wyatt said lamely. “You told me that yourself, just yesterday. Plays poker, too. Gives a man second thoughts.”

“She does not smoke cigars,” Lark insisted.

“So it’s true about the poker!” Rowdy said, in an ah-ha tone of voice.

“I wouldn’t know,” Lark said, with an indignant sniff.

“I heard she was a member of the Tuesday Afternoon Ladies Only Secret Poker Society,” Gideon said, looking smug. “And she’s not the only one. It might surprise you who goes to those meetings.”

Rowdy chuckled.

“Gideon,” Lark warned.

He turned back to the sink, flushed, and scrubbed industriously at the kettle Lark had used to boil up the morning’s oatmeal.

“It’s just a rumor,” Lark told Rowdy. “Respectable women do not play poker. Or smoke cigars.”

“Whatever you say, dear,” Rowdy replied sweetly.

Wyatt just shook his head, confounded.

“Come on,” Rowdy said to him, beckoning. “I’ll show you around town. Sam can swear you in when he gets here. What I do is, I count the horses in front of the saloons. If there’re more than a dozen, I keep a closer eye on the place—”

Wyatt followed, since that seemed like the only thing to do.

* * *

“THERE,” SAID SARAH, straightening her father’s tie outside the door of his office at the bank, grateful that the place was empty at the moment. Thomas, the only teller, had gone out when they arrived. The train would be pulling in at the new depot within an hour, pausing only long enough to swap mailbags with the postmaster and take on any passengers who might be waiting on the platform—or drop off new arrivals.

It was Thomas’s job, at least in part, to rush back to the bank and report to Sarah if any important visitors showed up. She was always on the lookout for unexpected stockholders.

“I’ll handle things, Papa,” Sarah assured her father, who had turned fretful again after breakfast. She was fairly certain he hadn’t seen her stuff his army uniform behind the wooden barrel of the washing machine on the back porch, but she wasn’t absolutely sure. “If someone comes in to open an account or inquire about a loan, let me do the talking. I’ll say you’re busy. All you have to do is sit at your desk, with your papers—if they insist on greeting you personally, I’ll be careful to call them by name so you know what to—”

“Sarah.” Ephriam looked pained.

“Papa, you know you forget.”

Just then, the street door opened with a crash, and Thomas burst in. Plump, with a constellation of smallpox scars spilling down one side of his face, he seemed on the verge of panic.

“Sarah!” he gasped, from the threshold, one fleshy hand pressed to his chest. “It’s him—the man in the photograph you showed me—”

Sarah’s knees turned to water. “No,” she said, leaning against her father for a moment. “He couldn’t possibly have—”

“It’s him,” Thomas repeated.

“Calm down,” Sarah said hastily. “Remember your asthma.”

Thomas struggled to a wooden chair, in front of the window, and sat there sucking in air like a trout on a creek bank. “S-Sarah, wh-what are we going to d-do—?”

“What,” Ephriam interjected, suddenly forceful, “is happening?”

Even in her agitation, Sarah felt a stab of sorrow, because she knew her father wouldn’t be his old self for more than a few minutes. When the inevitable fog rolled in, shrouding his mind again, she’d miss him more keenly than ever.

“You’re going to take Papa home,” she told Thomas, who had begun a moderate recovery—of sorts. He wasn’t sweating quite as much as he had been when he rushed in, and his breathing had slowed to a slight rasp. “Go out the back way, and stay off Main Street.”

Gamely, Thomas got to his feet again. Lumbered toward them.

When he took Ephriam’s arm, though, the old man pulled free. “Unhand me,” he said. “This is an outrage!”

Sarah’s mind was racing wildly through a series of possibilities, all of which were disastrous, but she’d had a lot of experience dealing with imminent disaster, and she rose to the occasion.

“Papa,” she said, “poor Thomas is feeling very ill. It’s his asthma, you know. If you don’t get him to Doc Venable, quickly, he could—” she paused, laid a hand to her bosom, fingers splayed, and widened her eyes “—perish!”

“Great Scot,” Ephriam boomed, taking Thomas by one arm and dragging him toward the front door, and the busy street outside, “the man needs medical attention! There’s not a moment to spare!”

Thomas cast a pitiable glance back at Sarah.

She closed her eyes, offered a hopeless prayer that Charles Elliott Langstreet the Third would get lost between the depot and the bank, and waited for the Apocalypse.

By the time Charles actually arrived, she was quite composed, at least outwardly, though faintly queasy and probably pale. She might have gotten through the preliminary encounter by claiming she was fighting off a case of the grippe, but as it turned out, Charles didn’t come alone.

He’d brought Owen with him.

Sarah’s heart lurched, caught itself like a running deer about to tumble down a steep hill. Perched on a stool behind the counter, in Thomas’s usual place, a ledger open before her, she nearly swooned.

Owen.

Ten years old now, blond like his imperious father, but with his grandfather’s clear, guileless blue eyes.

The floor seemed to tilt beneath the legs of Sarah’s stool. She gripped the edge of the counter to steady herself.

Charles smiled, enjoying her shock. He was handsome as an archangel, sophisticated and cruel, the cherished—and only—son of a wealthy family. And he owned a thirty percent interest in the Stockman’s Bank.

Owen studied her curiously. “Are you my aunt Sarah?” he asked.

Tears burned in Sarah’s eyes. She managed a nod, but did not trust herself to speak. If she did, she would babble and blither, and scare the child to death.

“Surprised?” Charles asked smoothly, still watching Sarah closely, his chiseled patrician lips taking on a sly curve.

“We came all the way from Philadelphia on a train,” Owen said, wide-eyed over the adventure. “I was supposed to spend the summer at school, but they sent me packing for putting a stupid girl down the laundry chute.”

Sarah blinked, found her voice. “Was she hurt?” she croaked, horrified.

“No,” Owen said, straightening his small shoulders. He was wearing a tweed coat and short pants, and he seemed to be sweltering. “She did the same thing to Mrs. Steenwilder’s cat, so I showed her how it felt.”

“The girl is fine,” Charles said. “And so is the cook’s cat.”

“We’re going to stay at the hotel,” Owen said. “Papa and me. I get to have my own room.”

“Why don’t you go over there right now and make sure the man we hired at the depot takes proper care of our bags?” Charles asked the little boy.

Owen nodded solemnly and left.

Sarah’s heart tripped after him—she had to drag it back. Corral it in her chest, where it pounded in protest.

“Why did you bring him?” she asked.

“I couldn’t leave the boy with Marjory,” Charles answered. “She despises him.”

Sarah squeezed her eyes shut, certain she would swoon.

“You must have known I’d come, Sarah. Someday.”

She opened her eyes again, stared at him in revulsion and no little fear. He’d moved while she wasn’t looking—come to stand just on the other side of the counter.

“If only because of the bank,” he went on softly, reaching out to caress her cheek. “After all, I have a sizable investment to look after.”

Sarah recoiled, but she still needed the stool to support her. “You’ve been receiving dividends every six months, as agreed,” she said coldly. “I know, because I made out the drafts myself.”

Charles frowned elegantly. His voice was as smooth as cream, and laced with poison. “Strange that you’d do that—given that Ephriam holds the controlling interest in this enterprise, not you.”

“It’s not strange at all,” Sarah said, but she was quivering on the inside. “Papa is very busy. He has a lot of other responsibilities.”

“All the more reason to offer my assistance,” Charles replied. He paused, studied her pensively. “Still beautiful,” he said. A smile quickened in his eyes, played on his mouth. “You’d like to run me off with a shotgun, wouldn’t you, Sarah?” he crooned. “But that would never do. Because when I leave, I’ll be taking our son with me.”

CHAPTER THREE

SAM O’BALLIVAN MUST HAVE BEEN an important man, Wyatt concluded, because they held the departing train for him. He arrived driving a wagon, with a boy and a baby and a pretty woman aboard, a string of horses traveling alongside, led by a couple of ranch hands. While all the baggage and mounts were loaded into railroad cars, Lark and Sam’s wife chattered like a couple of magpies on a clothesline.

Rowdy made the introductions, and Sam and Wyatt shook hands, standing there beside the tracks, the locomotive still pumping gusts of white steam. Sam was a big man, clear-eyed and broad-shouldered, with an air of authority about him. He not only owned the biggest ranch within miles of Stone Creek, he was an Arizona Ranger, which was the main reason he and Rowdy had been summoned to Haven.

“I hear you’re a fair hand with horses and cattle,” Sam said, in his deep, quiet voice.

The statement gave Wyatt a bit of a start, until he realized Sam was talking about ranch work, not rustling. “I can manage a herd, all right,” Wyatt confirmed.

Sam gave a spare smile. His gaze penetrated deep, like Rowdy’s, and it was unsettling. “I’m looking for a range foreman,” the rancher said. “Job comes with a cabin and meals in the bunkhouse kitchen. Fifty dollars a month. Would you be interested?”

Rowdy must have seen that Wyatt was surprised by the offer, given that he was a stranger to O’Ballivan, because he explained right away. “I told Sam all about you.”

“All of it?” Wyatt asked, searching his brother’s face.

“I know you did some time down in Texas,” Sam said.

Wyatt stole a glance at the pretty woman laughing and comparing babies with Lark a few yards away. A tall boy stood nearby, waiting impatiently to board the train. “And that doesn’t bother you? Having a jailbird on your place, with your family there and all?”

“Rowdy’s willing to vouch for you,” Sam said. “That’s good enough for me.”

Wyatt looked at Rowdy with new respect. What would it be like to be trusted like that?

“I figure we ought to appoint Wyatt deputy marshal,” Rowdy said. “Being the mayor of Stone Creek, you’d have to swear him in.”

Sam nodded, but he was still looking deep enough to see things Wyatt didn’t want to reveal. “Do you swear to uphold the duties of deputy marshal?” he asked.

“Yes,” Wyatt heard himself say.

Rowdy handed him his badge just as Gideon showed up, a pair of bulging saddlebags over one shoulder, the old yellow dog padding along behind him.

“Pardner’s going, too,” Gideon said, apparently braced for an objection.

Nobody raised one.

Inside the locomotive, the engineer blew the whistle.

“Guess we’d better get going,” Rowdy said, with a grin. “The train’s got a schedule to keep.”

With that, there was some hand-shaking, and some fare-thee-wells, then the whole crowd of them boarded, even the yellow dog. Wyatt stood there, Rowdy’s star-shaped badge heavy in his left hand, and wondered how he’d gotten himself into this situation. It was all well and good to figure on running for it before Sam and Rowdy caught up to what was left of the Justice gang and learned that he, Wyatt, had ridden with the sorry outfit. The trouble was, except for stealing one of his brother’s horses, a thing Rowdy had rightly guessed he could not do, and taking to the trail, he didn’t have any choice but to stay right there in Stone Creek.

Hell, he might as well just shut himself up behind the cell door over there in the jailhouse right now and be done with it.

He watched, feeling a strange combination of misery and anticipation, as the train pulled out of the depot onto a curved spur, Stone Creek being at present the end of the line, and snaked itself around to chug off in the other direction. Steam billowed from the smokestack as it picked up speed.

When he turned to walk away, he almost collided with a small boy in knee pants and a woolen coat.

The kid’s gaze fastened on Rowdy’s star as Wyatt pinned it to his shirt.

“You the law around here?” the boy asked, squinting against the bright August sun as he looked up at Wyatt.

“For the moment,” Wyatt said.

“Owen Langstreet,” the child replied, putting out a small hand with manly solemnity. “I got expelled from school for throwing a girl named Sally Weekins down the laundry chute. Not that you can arrest me or anything, Sheriff—?”

“Name’s Wyatt Yarbro,” Wyatt told young Mr. Langstreet, “and I’m not the sheriff. That’s an elected office, one to a county. Reckon my proper title is ‘deputy marshal.’ Why would you go and dump somebody down a laundry chute?”

“It’s a long story,” Owen answered. “She didn’t get hurt, and you can’t arrest me for it, anyhow. It happened in Philadelphia, and that’s outside your jurisdiction.”

Wyatt frowned. “How old are you?”

“Ten,” Owen said.

“I’d have pegged you for at least forty.” Wyatt started back for the main part of town, one street over, figuring he ought to walk around and look like he was marshaling. He wasn’t looking forward to going back to the jail; it would be a lonely place, with nobody else around.

“There probably aren’t any laundry chutes in Stone Creek,” Owen went on, scrambling to keep up. “Papa says it’s a one-horse, shit-heel town in the middle of nowhere. Even the hotel only has two stories. And no elevator.”

“That so?” Wyatt replied. The kid talked like a brat, using swearwords and bragging about poking a girl down a chute, but there was something engaging about him, too. He wasn’t pestering Wyatt out of devilment; he wanted somebody to talk to.

Wyatt knew the feeling.

“He’s going to take Aunt Sarah’s bank away from her,” Owen said.

Wyatt stopped cold, looked down at the kid, frowning. “What?”

“Papa says there’s something rotten in Denmark.”

“Just who is your papa, anyhow?”

“His name is Charles Langstreet the Third,” Owen replied matter-of-factly. “You’ve heard of him, haven’t you?”

“Can’t say as I have,” Wyatt admitted, setting his course for the Stockman’s Bank, though he had no business there, without a dime to his name. If Sarah was around, he’d tell her he was Rowdy’s deputy now, out making his normal rounds. It made sense for a lawman to keep an eye on the local bank, didn’t it?

“He’s very rich,” Owen said. “I’m going to have to make my own way when I grow up, though. Mother said so. I needn’t plan on getting one nickel of the Langstreet fortune, since I’m a bastard.”

As concerned as he was about Sarah, and the fact that some yahoo called Charles Langstreet the Third was evidently plotting to relieve her of the Stockman’s Bank, Wyatt stopped again and looked down at Owen. “Your mother called you a bastard?”

Owen nodded, unfazed. “It means—”

“I know what it means,” Wyatt interrupted. “Does this papa of yours know you’re running loose in a cow town, all by yourself?”

“I’m not by myself,” Owen reasoned. “I’m with you. And you’re a deputy. What could happen to me when you’re here?”

“The point is,” Wyatt continued, walking again, “he doesn’t know you’re with me, now does he?”

“He knows everything,” Owen said, with certainty. “He’s very clever. People tip their hats to him and call him ‘sir.’”

“Do they, now?”

The bank was in sight now, and Wyatt saw a tall man, dressed Eastern, leaving the establishment, straightening his fancy neck rigging as he crossed the wooden sidewalk, heading for the street.

Spotting Owen walking with Wyatt, the man smiled broadly and approached. “There you are, you little scamp,” he told the boy, ruffling the kid’s hair.

“This is Wyatt Earp,” Owen said. That explained all the chatter.

“Wyatt Yarbro.”

“Charles Langstreet,” said the dandy. He didn’t extend his hand, which was fine with Wyatt.

Wyatt glanced over Langstreet’s shoulder, hoping to catch a glimpse of Sarah through the bank’s front window. He didn’t know much about Owen’s papa—but he figured him for trouble, all right.

“You’re not Wyatt Earp?” Owen asked, looking disappointed.

“No,” Wyatt said. “Sorry.”

“But you’ve got a gun and a badge and everything.”

“Come along,” Langstreet told the boy, though his snake-cold eyes were fixed on Wyatt’s face. “Aunt Sarah has invited us to supper, and we’ll need to have baths and change our clothes.” His gaze sifted over Wyatt’s borrowed duds, which had seen some use, clean though they were. “A good day to you—Deputy.”

With that, the confab ended, and Langstreet shepherded the boy toward the town’s only hotel. Owen looked back, once or twice, curiously, as if trying to put the pieces of a puzzle together.

Wyatt made for the bank. A little bell jingled over the door as he entered.

Sarah, standing behind the counter, looked alarmed, then rallied.

“Oh, it’s you,” she said.

Wyatt took off his round-brimmed black hat and tried for an easy smile, but the truth was, the inside of that bank felt charged, like the floor might suddenly rip wide open, or thunder might shake the ceiling over their heads. “Everything all right, Miss Tamlin?”

She blinked. “Of course everything is fine, Mr. Yarbro. Whyever would you ask such a question?”

“Partly because it’s my job.” He indicated the star on his shirt. “I’ll be looking after Stone Creek while Rowdy’s out of town. And partly because I just met a boy named Owen Langstreet down by the depot.”

She paled. “What did he tell you?”

“Just that his father means to take the bank away from you.”

Sarah tried to lasso a smile, but the rope landed short. “This bank belongs to my father, not to me. Mr. Langstreet is merely a—a shareholder. There is no need to be concerned, Mr. Yarbro, though I do appreciate it.”

Wyatt nodded, went to the door, replaced his hat. “I’m a friend, Sarah,” he said. “Remember that.”

She swallowed visibly, nodded back.

Wyatt opened the door.

“Mr. Yarbro?”

He stopped, waited. Said nothing.

Sarah’s voice trembled. “I wonder if you’d join us for supper tonight? Six o’clock?”

“I’d like that,” Wyatt said.

“We’ll be expecting you, then,” Sarah replied brightly.

Wyatt touched his hat brim again and left.

Walking back along Main Street, toward Rowdy’s office, he was intercepted repeatedly; evidently, word had gotten around town that while Marshal Yarbro was away, he’d be watching the store. Folks were friendly enough, if blatantly curious, and Wyatt offered them no more than a “howdy” and an amicable nod.

Thoughts were churning inside his head like bees trying to get out from under an overturned bucket. He meant to leave Stone Creek. He meant to stay.

He didn’t know what the hell he was going to do.

Distractedly, he counted the horses in front of every saloon he passed—the town had more than its share, considering its size—saw no reason for concern, and went on to the jailhouse. Now that he had a supper invitation from Sarah, his spirits had lifted, though he was under no illusion that she’d asked him over out of any desire to socialize. She didn’t want to be alone with Langstreet, that was all; she was terrified of him, and it was more than the threat of losing control of the bank.

Back at the jail, Wyatt collected his bedroll and saddlebags from the cell where he’d passed the night and headed for the small barn out behind Rowdy’s house. He’d bunk out there in the hayloft, he’d decided, with Reb and the other horses. He’d be behind bars again soon enough, if Rowdy and Sam caught up with Billy Justice. Soon as Billy heard the name Yarbro, he’d put paid to any hope Wyatt had of living as a free man.

He could lie, of course. Say he’d never crossed paths with the gang, let alone helped them rustle cattle. His word against Billy’s. Sam might even believe him—but Rowdy wouldn’t. No, Rowdy’d see right through to the truth.

Inside the barn, Wyatt tossed his few belongings up into the low-hanging loft, and the sweet smell of fresh hay stirred, along with a shower of golden dust.

Reb nickered a greeting, and Wyatt crossed to the stall to stroke the animal’s long face. “You like it here, don’t you, boy?” he asked. “Time you led the easy life.”

Wyatt added hay to Reb’s feeding trough, then to those of the other two horses. He carried water in from the well to fill their troughs.

Rowdy’s spare horse was a buckskin gelding named Sugarfoot. He looked capable of covering a lot of ground—he and Sugarfoot could be a long way from Stone Creek in a short time. Maybe he’d leave a note for Rowdy, on the kitchen table, along with the badge, saying he was sorry and promising to send payment for the horse as soon as he got work.

He closed his eyes against the emotions that rose up in him then—shame, frustration, regret—and a hopeless yearning for the kind of life his younger brother had. Rowdy would understand; he’d been on the run himself. But if he found out about Wyatt’s brief association with Billy’s gang, he might come after him, not as a brother, but as a lawman.

And there was more.

He’d never see Sarah again, or poor old Reb.

He sighed, shoved a hand through his hair.

After a few moments, he made for the house. He’d been kidding himself, thinking he could stop running and put down some roots. Now, he was going to have to cut himself loose, and it would hurt—a lot.

Entering by the kitchen door, Wyatt noticed the envelope propped against the kerosene lamp in the center of the table right away. Took it into his hands.

Rowdy had scrawled his name on the front.

After letting out a long breath, he slid a thumb under the flap, found a single sheet of paper inside, along with three ten-dollar bills.