Полная версия

Полная версияThe Lifeboat

Lukin, though a man of energy and perseverance, was doomed to disappointment. The Prince of Wales (George the Fourth), to his credit be it said, was his warm and liberal patron, but even the Prince’s influence failed to awaken the sympathy of the public, or of the men in high places who alone could bring this great invention into general use. People in those days appeared to think that the annual drowning of thousands of their countrymen was an unavoidable necessity,—the price we had to pay, as it were, for our maritime prosperity. Lukin appealed in vain to the First Lord of the Admiralty, and to many other influential men, but a deaf ear was invariably turned to him. With the exception of the Bamborough coble, not a single lifeboat was placed at any of the dangerous localities on the east coast of England for several years. Wrecked men and women and children were (as far as the Naval Boards were concerned) graciously permitted to swim ashore if they could, or to go to the bottom if they couldn’t! Ultimately, the inventor of the lifeboat went to his grave unrewarded and unacknowledged—at least by the nation; though the lives saved through his invention were undoubtedly a reward beyond all price. The high honour of having constructed and set in motion a species of boat which has saved hundreds and thousands of human lives, and perchance prevented the breaking of many human hearts, is certainly due to Lionel Lukin.

In 1789, the public were roused from their state of apathy in regard to shipwrecked seamen by the wreck of the “Adventure” of Newcastle, the crew of which perished in the presence of thousands who could do nothing to save them. Under the excitement of this disaster the inhabitants of South Shields met to deplore and to consult. A committee was appointed, and premiums were offered for the best models of lifeboats. Men came forward, and two stood pre-eminent—Mr William Wouldhave, a painter, and Mr Henry Greathead, a boat-builder, of South Shields. The former seems to have been the first who had a glimmering idea of the self-righting principle, but he never brought it to anything. Cork was the buoyant principle in his boat. Greathead suggested a curved keel. The chairman of the committee modelled a boat in clay which combined several of the good qualities of each, and this was given to Greathead as the type of the boat he was to build.

From this time forward lifeboats gradually multiplied. Greathead became a noted improver and builder of them. He was handsomely rewarded for his useful labours by Government and others, and his name became so intimately and deservedly associated with the lifeboat, that people erroneously gave him the credit of being its inventor.

The Duke of Northumberland took a deep interest in the subject of lifeboats, and expended money liberally in constructing and supporting them. Before the close of 1863, Greathead had built 31 boats, 18 for England, 5 for Scotland, and 8 for foreign countries. This was so far well; but it was a wretchedly inadequate provision for the necessities of the case. Interest had indeed been awakened in the public, but the public cannot act as a united body; and the Trinity House seemed to fall back into the sleep from which it had been partially aroused.

It was not till 1822 that the great (because successful) champion of the lifeboat stood forth,—in the person of Sir William Hillary, Baronet.

Sir William, besides being a philanthropist, was a hero! He not only devised liberal things, and carried them into execution, but he personally shared in the danger of rescuing life from the raging sea. Our space forbids a memoir, but this much may be said briefly. He dwelt on the coast of the Isle of Man, and established a Sailors’ Home at Douglas. He constantly witnessed the horrors of shipwreck, and seemed to make it his favourite occupation to act as one of the crew of boats that put off to wrecks. He was of course frequently in imminent danger; once had his ribs broken, and was nearly drowned oftentimes. During his career he personally assisted in saving 305 lives! He was the means of stirring up public men, and the nation generally, to a higher sense of their duty to those who risk their lives upon the sea; and eventually—in conjunction with two members of Parliament, Mr Thomas Wilson and Mr George Hibbert—was the founder of “The Royal National Institution for the Preservation of Life from Shipwreck.”

This noble Institution—now named The Royal National Lifeboat Institution—was founded on the 4th of March, 1824. From that date to the present time it has unremittingly carried out the great ends for which it was instituted.

Let us glance at these in detail, as given in their publication, The Lifeboat Journal.

The objects of the Institution are effected—

“1st, By the stationing of lifeboats, fully equipped, with all necessary gear and means of security to those who man them, and with transporting carriages on which they can be drawn by land to the neighbourhood of distant wrecks, and by the erection of suitable houses in which the same are kept.

“2nd, By the appointment of paid coxswains, who have charge of, and are held responsible for, the good order and efficiency of the boats, and by a quarterly exercise of the crew of each boat.

“3rd, By a liberal remuneration of all those who risk their lives in going to the aid of wrecked persons, whether in lifeboats or otherwise; and by the rewarding with the gold or silver medal of the Institution such persons as encounter great personal risk in the saving of life.

“4th, By the superintendence of an honorary committee of residents in each locality, who, on their part, undertake to collect locally what amount they are able of donations towards the first cost, and of annual contributions towards the permanent expenses of their several establishments.”

In order to see how this work is, and has been, carried out, let us look at the results, as stated in the last annual report, that for 1864.

The lifeboats of the Institution now number 132, and some of them were the means of saving no fewer than 417 lives during the past year; nearly the whole of them in dangerous circumstances, amidst high surfs, when no other description of boats could have been launched with safety. They also took into port, or materially assisted, 17 vessels, which might otherwise have been lost. The number of persons afloat in the boats on occasions of their being launched was 6,000. In other words, our army of coast-heroes amounts, apparently, to that number. But in reality it is much larger, for there are hundreds of willing volunteers all round the coast ready to man lifeboats, if there were lifeboats to man. Although nearly every man of this 6000 risked his life again and again during the year, not a single life was lost.

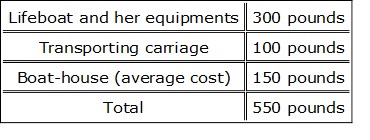

Nearly all these boats have been supplied with transporting carriages and boat-houses by the Institution. The cost in detail is as follows:—

The sums granted last year for the saving of 714 lives by lifeboats, shore-boats, etcetera, amounted to nearly 1,300 pounds (about 1 pound 16 shillings 6 pence each life!) Fifteen silver medals and twenty-six votes of thanks, inscribed on vellum and parchment, were also awarded for acts of extraordinary gallantry.

The income of the Institution in 1863 amounted to 21,100 pounds. Fifteen new lifeboats were sent to various parts of the coast in that year.

It is interesting to observe in the report the persons by whom donations are sometimes given to the Institution. We read of “100 pounds from a sailor’s daughter”; and “100 pounds as a thank-offering for preservation at sea, during the storm of 31st October last.” Another thank-offering of 20 pounds, “for preservation from imminent danger at sea,” appears in the list. “100 pounds from ‘a friend,’ in gratitude to God for the preservation of his wife for another year”; and “20 pounds from a seaman’s daughter, the produce of her needle-work.” Among smaller sums we find 1 pound, 6 shillings, 9 pence collected in a Sunday school; 3 pounds, 18 shillings, 8 pence collected in a parish church, as a New Year’s offering. Last, and least in one sense, though by no means least in another, 1 shilling, 6 pence in stamps, from a sailor’s orphan child!

The prayer naturally springs to one’s lips, God bless that dear orphan child! but it has been already blessed with two of God’s choicest gifts,—a sympathetic heart and an open hand.

Small sums like this are not in any sense to be despised. If the population of London alone—taking it at two millions—were individually to contribute 1 shilling, 6 pence, the sum would amount to 150,000 pounds! Why, if everyone whose eye falls on this page—to descend to smaller numbers—were to give a shilling, it is not improbable that a sum would be raised sufficient to establish two lifeboats!3

But there are those who, besides being blessed with generous hearts, are fortunate in possessing heavy purses. We find in the same report donations of from two hundred to two thousand pounds, and legacies ranging from ten to a thousand pounds. The largest legacy that seems ever to have been bequeathed to the Institution was that of 10,000 pounds, left in 1856 by Captain Hamilton Fitzgerald, R.N., one of the vice-presidents of the Society.

The mere mention of such sums may induce some to imagine that the coffers of the Institution are in a very flourishing state. This would indeed be the case if the Society had reached its culminating point—if everything were done that can be done for the preservation of life from shipwreck; but this is by no means the case. It must be borne in mind that the Institution is national. The entire coasts of the United Kingdom are its field of operations, and the drain upon its resources is apparently quite equal to its income. Its chief means of support are voluntary contributions.

Since the Society was instituted, in 1824, to the present time, it has been the means of saving 13,570 lives!—many, if not most, of these being lives of the utmost consequence to the commerce and defence of the country. During the same period, it has granted 82 gold medals, 736 silver medals, and 17,830 pounds in cash; besides expending 82,550 pounds on boats, carriages, and boat-houses.

Considering, then, the magnitude and unavoidable costliness of the operations of this Institution, it is evident that a large annual income is indispensable, if it is to continue its noble career efficiently.

Closely allied to this is another society which merits brief notice here. It is the “Shipwrecked Fishermen’s and Mariners’ Royal Benevolent Society.” Originally this Society, which was instituted in 1839, maintained lifeboats on various parts of the coast. It eventually, however, made these over to the Lifeboat Institution, and confined itself to its own special and truly philanthropic work, which is—

To board, lodge, and convey to their homes, all destitute, shipwrecked persons, to whatever country they may belong, through the instrumentality of its agents. To afford temporary assistance to the widows, parents, and children of all mariners and fishermen who may have been drowned, and who were members of the Society; and to give a gratuity to mariners and fishermen, who are members, for the loss or damage of their clothes or boats. Membership is obtained by an annual subscription of three shillings.

Assuredly every mariner and fisherman in the kingdom ought to be a member of this Society, for it is pre-eminently useful, and no one can tell when he may require its assistance.

The Lifeboat Institution and the Shipwrecked Fishermen’s and Mariners’ Society are distinct bodies, but they do their benevolent work in harmonious concert. The one saves life, or tries to save it; the other cherishes the life so saved, or comforts and affords timely aid to broken-hearted mourners for the dead.

Both Institutions are national blessings, and as such have the strongest possible claim on the sympathies of the nation.

Chapter Twenty Four.

A Meeting—A Death, and a Discovery

Resuming our story, we remind the reader that we left off just as the Ramsgate lifeboat had gained a glorious victory over a great storm.

Availing ourselves of an author’s privilege, we now change the scene to the parlour of Mrs Foster’s temporary lodgings at Ramsgate, whither the worthy lady had gone for change of air, in company with her son Guy, her daughter-in-law Lucy, her little grandson Charlie, and her adopted daughter Amy Russell.

Bax is standing there alone. He looks like his former self in regard to costume, for the only man approaching his own size, who could lend him a suit of dry clothing, happened to be a boatman, so he is clad in the familiar rough coat with huge buttons, the wide pantaloons, and the sou’-wester of former days. His countenance is changed, however; it is pale and troubled.

On the way up from the harbour Guy had told him that he was married, and was surprised when Bax, instead of expressing a desire to be introduced to his wife, made some wild proposal about going and looking after the people who had been saved! He was pleased, however, when Bax suddenly congratulated him with great warmth, and thereafter said, with much firmness, that he would go up to the house and see her. On this occasion, also, Bax had told his friend that all the produce of his labour since he went away now lay buried in the Goodwin Sands.

Bax was ruminating on these things when the door opened, and Guy entered, leading Lucy by the hand.

“Miss Burton!” exclaimed Bax, springing forward.

“My wife,” said Guy, with a puzzled look.

“Bax!” exclaimed Lucy, grasping his hand warmly and kissing it; “surely you knew that I was married to Guy?”

Bax did not reply. His chest heaved, his lips were tightly compressed, and his nostrils dilated, as he gazed alternately at Guy and Lucy. At last he spoke in deep, almost inaudible tones:

“Miss Russell—is she still—”

“My sister is still with us. I have told her you are come. She will be here directly,” said Guy.

As he spoke the door opened, and Mrs Foster entered, with Amy leaning on her arm. The latter was very pale, and trembled slightly. On seeing Bax the blood rushed to her temples, and then fled back to her heart. She sank on a chair. The sailor was at her side in a moment; he caught her as she was in the act of falling, and going down on one knee, supported her head on his shoulder.

“Bring water, she has fainted,” he cried. “Dear Miss Russell!—dearest Amy!—oh my beloved girl, look up.”

Stunned and terrified though poor Mrs Foster was, as she rushed about the room in search of water and scent-bottles, she was taken aback somewhat by the warmth of these expressions, which Bax, in the strength of his feelings, and the excitement of the moment, uttered quite unconsciously. Guy was utterly confounded, for the truth now for the first time flashed upon him, and when he beheld his friend tenderly press his lips on the fair forehead of the still insensible Amy, it became clear beyond a doubt. Lucy was also amazed, for although she was aware of Amy’s love for Bax, she had never dreamed that it was returned.

Suddenly Guy’s pent-up surprise and excitement broke forth. Seizing Mrs Foster by the shoulders, he stared into her face, and said, “Mother, I have been an ass! an absolute donkey!—and a blind one, too. Oh!—ha! come along, I’ll explain myself. Lucy, I shall require your assistance.”

Without more ado Guy led his mother and Lucy forcibly out of the room, and Bax and Amy were left alone.

Again we change the scene. The Sandhills lying to the north of Deal are before us, and the shadows of night are beginning to deepen over the bleak expanse of downs. A fortnight has passed away.

During that period Bax experienced the great delight of feeling assured that Amy loved him, and the great misery of knowing that he had not a sixpence in the world. Of course, Guy sought to cheer him by saying that there would be no difficulty in getting him the command of a ship; but Bax was not cheered by the suggestion; he felt depressed, and proposed to Guy that they should take a ramble together over the Sandhills.

Leaving the cottage, to which the family had returned the day before, the two friends walked in the direction of Sandown Castle.

“What say you to visit old Jeph?” said Guy; “I have never felt easy about him since he made me order his coffin and pay his debts.”

“With all my heart,” said Bax. “I spent a couple of hours with him this forenoon, and he appeared to me better than usual. Seeing Tommy and me again has cheered him greatly, poor old man.”

“Stay, I will run back for the packet he left with me to give to you. He may perhaps wish to give it you with his own hand.”

Guy ran back to the cottage, and quickly returned with the packet.

Old Jeph’s door was open when they approached his humble abode. Guy knocked gently, but, receiving no answer, entered the house. To their surprise and alarm they found the old man’s bed empty. Everything else in the room was in its usual place. The little table stood at the bedside, with the large old Bible on it and the bundle of receipts that Guy had placed there on the day he paid the old man’s debts. In a corner lay the black coffin, with the winding-sheet carefully folded on the lid. There was no sign of violence having been done, and the friends were forced to the conclusion that Jeph had quitted the place of his own accord. As he had been confined to bed ever since his illness—about two weeks—this sudden disappearance was naturally alarming.

“There seems to have been no foul play,” said Bax, examining hastily the several closets in the room. “Where can he have gone?”

“The tomb!” said Guy, as Jeph’s old habit recurred to his memory.

“Right,” exclaimed Bax, eagerly. “Come, let’s go quickly.”

They hastened out, and, breaking into a smart run, soon reached the Sandhills. Neither of them spoke, for each felt deep anxiety about the old man, whose weak condition rendered it extremely improbable that he could long survive the shock that his system must have sustained by such a walk at such an hour.

Passing the Checkers of the Hope, they soon reached Mary Bax’s tomb. The solitary stone threw a long dark shadow over the waste as the moon rose slowly behind it. This shadow concealed the grave until they were close beside it.

“Ah! he is here,” said Bax, kneeling down.

Guy knelt beside him, and assisted to raise their old friend, who lay extended on the grave. Bax moved him so as to get from beneath the shadow of the stone, and called him gently by name, but he did not answer. When the moonlight next moment fell on his countenance, the reason of his silence was sufficiently obvious.

Old Jeph was dead!

With tender care they lifted the body in their arms and bore it to the cottage, where they laid it on the bed, and, sitting down beside it, conversed for some time in low sad tones.

“Bax,” said Guy, pulling the sealed packet from his breast-pocket, “had you not better open this? It may perhaps contain some instructions having reference to his last resting-place.”

“True,” replied Bax, breaking the seals. “Dear old Jeph, it is sad to lose you in this sudden way, without a parting word or blessing. What have we here?” he continued, unrolling several pieces of brown paper. “It feels like a key.”

As he spoke a small letter dropt from the folds of the brown paper, with an old-fashioned key tied to it by a piece of twine. Opening the letter he read as follows:—

“Dear Bax,—When you get this I shall be where the wicked cease from troubling, and the weary are at rest. There is a hide in the north-west corner of my room in the old house, between the beam and the wall. The key that is enclosed herewith will open it. I used to hide baccy there in my smugglin’ days, but since I left off that I’ve never used it. There you will find a bag of gold. How much is in it I know not. It was placed there by an old mate of mine more than forty years ago. He was a great man for the guinea trade that was carried on with France in the time of Boney’s wars. I never rightly myself understood that business. I’m told that Boney tried to get all the gold out o’ this country, by payin’ three shillings more than each guinea was worth for it, but that seems unreasonable to me. Hows’ever, although I never could rightly understand it, there is no doubt that some of our lads were consarned in smugglin’ guineas across the channel, and two or three of ’em made a good thing of it. My mate was one o’ the lucky ones. One night he came home with a bag o’ gold and tumbled it out on the table before me. I had my suspicions that he had not come honestly by it, so would have nothin’ to do with it. When I told him so, he put it back into the bag, tied it up, and replaced it in the hide, and went away in a rage. He never came back. There was a storm from the east’ard that night. Two or three boats were capsized, and my mate and one or two more lads were drowned. The guineas have lain in the hide ever since. I’ve often thought o’ usin’ them; but somehow or other never could make up my mind. You may call this foolish, mayhap it was; anyhow I now leave the gold to you;—to Tommy, if you never come back, or to Guy if he don’t turn up. Bluenose don’t want it: it would only bother him if I put it in his way.

“This is all I’ve got to say: The old house ain’t worth much, but such as it is, it’s yours, or it may go the same way as the guineas.

“Now, Bax, may God bless you, and make you one of His own children, through Jesus Christ. My heart warms to you for your own sake, and for the sake of her whose name you bear. Farewell.—Your old friend and mate, Jeph.”

Bax stooped over the bed, and pressed his lips to the dead man’s forehead, when he had finished reading this letter. For some time the two friends sat talking of old Jeph’s sayings and doings in former days, forgetful of the treasure of which the epistle spoke. At last Bax rose and drew a table to the corner mentioned in the letter. Getting upon this, he found an old board nailed against the wall.

“Hand me that axe, Guy; it must be behind this.”

The board was soon wrenched off, and a small door revealed in the wall. The key opened it at once, and inside a bag was found. Untying this, Bax emptied the glittering contents on the table. It was a large heap, amounting to five hundred guineas!

“I congratulate you, Bax,” said Guy; “this removes a great difficulty out of your way. Five hundred guineas will give you a fair start.”

“Do you suppose that I will appropriate this to myself?” said Bax. “You and Tommy are mentioned in the letter as well as me.”

“You may do as you please in regard to Tommy,” said Guy, “but as for me, I have a good salary, and won’t touch a guinea of it.”

“Well, well,” said Bax, with a sad smile, “this is neither the time nor place to talk of such matters. It is time to give notice of the old man’s death.”

Saying this, he returned the gold to its former place, locked the hide, and replaced the board. As he was doing this, a peculiar cut in the beam over his head caught his eye.

“I do believe here is another hide,” said he. “Hand the axe again.”

A piece of wood was soon forced out of the side of the beam next the wall, and it was discovered that the beam itself was hollow. Nothing was found in it, however, except a crumpled piece of paper.

“See here, there is writing on this,” said Guy, picking up the paper which Bax flung down. “It is a crabbed hand, but I think I can make it out:– ‘Dear Bogue, you will find the tubs down Pegwell Bay, with the sinkers on ’em; the rest of the swag in Fiddler’s Cave.’”

“Humph! an old smuggler’s letter,” said Bax. “Mayhap the tubs and swag are there yet!”

We may remark here, that, long after the events now related, Bax and Guy remembered this note and visited the spots mentioned out of curiosity, but neither “tubs” nor “swag” were found!

Quitting the room with heavy hearts, the two friends locked the door, and went in search of those who are wont to perform the last offices to the dead.

Chapter Twenty Five.

The Conclusion

There came a day at last when the rats in Redwharf Lane obtained an entire holiday, doubtless to their own amazement, and revelled in almost unmolested felicity from morning till night. The office of Denham, Crumps, and Company was shut; the reason being that the head of the firm was dead.