Полная версия

Полная версияMan on the Ocean: A Book about Boats and Ships

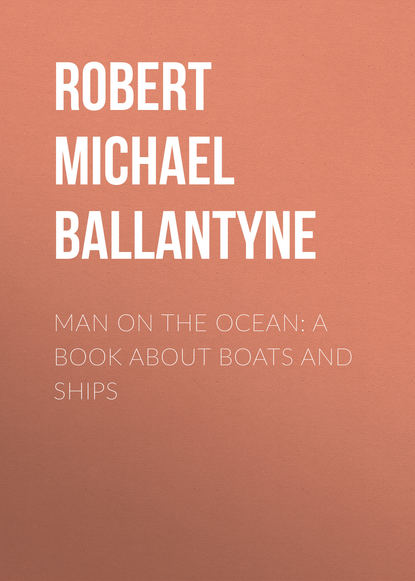

Shrouds and stays are the thick ropes that keep the masts firmly in position. They form part of what is termed the “standing gear” of a ship—in other words, the ropes that are fixtures—to distinguish them from the “running gear”—those movable ropes, by means of which the sails, boats, flags, etcetera, are hoisted. Nearly all the ropes of a ship are named after the mast, or yard, or sail with which they are connected. Thus we have the main shrouds, the main-top-mast shrouds, and the main-topgallant shrouds; the main back-stay, the main-topgallant back-stay, and so on—those of the other masts being similarly named, with the exception of the first word, which, of course, indicates the particular mast referred to. The shrouds rise from the chains, which are a series of blocks called “dead eyes,” fixed to the sides of the ship. To these the shrouds are fixed, and also to the masts near the tops; they serve the purpose of preventing the masts from falling sideways. Backstays prevent them from falling forward, and forestays prevent them from falling backward, or “aft.” Besides this, shrouds have little cross ropes called ratlines attached to them, by means of which rope-ladders the sailors ascend and descend the rigging to furl, that is, tie up, or unfurl, that is, to untie or shake out, the sails.

Our cut represents a sailor-boy ascending the mizzen-top-mast shrouds. He grasps the shrouds, and stands on the ratlines.

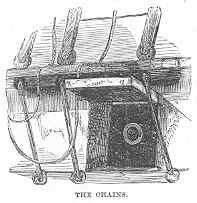

Yards are the heavy wooden cross-poles or beams to which the sails are attached.

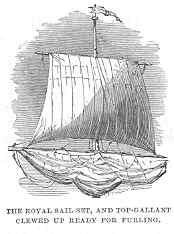

Reef-points are the little ropes which may be observed hanging in successive rows on all sails, by means of which parts of the sails are gathered in and tied round the yards, thus reducing their size in stormy weather. Hence such nautical expressions as “taking in a reef,” or a “double reef,” and “close reefing,”—which last implies that a sail is to be reduced to its smallest possible dimensions. The only further reduction possible would be folding it up altogether, close to the yard, which would be called “furling” it, and which would render it altogether ineffective. In order to furl or reef sails, the men have to ascend the masts, and lay-out upon the yards. It is very dangerous work in stormy weather. Many a poor fellow, while reefing sails in a dark tempestuous night, has been blown from the yard into the sea, and never heard of more. All the yards of a ship, except the three largest, can be hoisted and lowered by means of halyards. The top-gallant masts can also be lowered, but the lower-masts, of course, are fixtures.

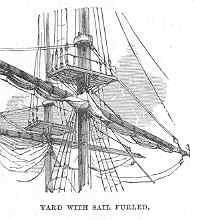

The bowsprit of a ship is a mast which projects out horizontally, or at an angle, from the bow. It is sometimes in two or three pieces, sometimes only in one. To it are attached the jib-sail and the flying-jib, besides a variety of ropes and stays which are connected with and support the fore-mast.

The cat heads are two short beams which project from the bows on either side, and support the ship’s anchors.

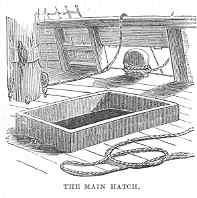

Miscellaneous.—The openings in the decks are called hatches; the stair-cases which descend to the cabins are called companions. The pulleys by which sails, etcetera, are hoisted, are named blocks. Braces are the ropes by which sails are fixed tightly in any position. Hauling a rope taut, means hauling it tight. The weather side of a ship means the side which happens to be presented to the wind; the lee side, that which is away from the wind, and, therefore, sheltered. The starboard side means the right side, the larboard signifies the left; but as the two words resemble each other, the word port is always used for larboard to prevent mistakes in shouting orders. Heaving the lead is the act of throwing a heavy leaden plummet, with a line attached, into the sea to ascertain its depth. It is thrown from the chains as far as possible ahead of the ship, so that it may reach the bottom and be perpendicularly beneath the man who heaves it when the ship comes up to the spot where it entered the water. A peculiar and musical cry is given forth by the heaver of the lead each time he throws it. The forecastle is the habitat of the ordinary sailors, and is usually in nautical parlance termed the foge-s’l.

Most of what we have just described applies more or less to every ship; but this will be seen in future chapters. Meanwhile, we would seriously recommend all those who have found this chapter a dry one to turn back to the heading entitled “Rigging a Ship,” and from that point read it all over again with earnest attention.

Chapter Ten.

Coasting Vessels

The coasting-trade of the British Islands is replete with danger, yet it is carried on with the utmost vigour; and there are always plenty of “hands,” as seamen are called when spoken of in connection with ships, to man the vessels. The traffic in which they are engaged is the transporting of the goods peculiar to one part of our island, to another part where they are in demand.

In describing these vessels, we shall begin with the smallest.

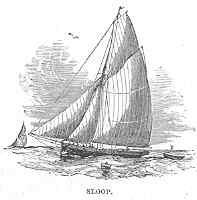

Sloops

Like all other vessels, sloops vary in size, but none of them attain to great magnitude. As a class, they are the smallest decked vessels we have. From 40 to 100 tons burden is a very common size. A sloop of 40 tons burden is what we ordinarily call a little ship, and one of 100 tons is by no means a big one. The hull of such a vessel being intended exclusively to carry cargo, very little space is allowed for the crew. The cabins of the smaller-sized sloops are seldom high enough to permit of an ordinary man standing erect. They are usually capable of affording accommodation to two in the cabin, and three or four in the forecastle,—and such accommodation is by no means ample. The class to which vessels belong is determined chiefly by the number of their masts and by the arrangement and the form of their sails.

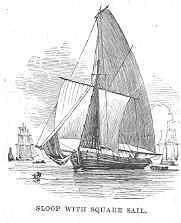

The distinctive peculiarity of the sloop is, that it has but one mast; and its rig is, nautically speaking, fore-and-aft—that is to say, the sails are spread with their surfaces parallel to the sides of the vessel, not stretched upon yards across the vessel. The term “fore-and-aft” is derived from the forward part and the after part of the ship. Fore-and-aft sails, then, are such as are spread upon yards which point fore and aft, not across the ship. We conceive this elaborate explanation to be necessary for some readers, and, therefore, don’t apologise for making it. A ship whose sails are spread across the hull is said to be square-rigged. Sometimes, however, a sloop carries one and even two square sails.

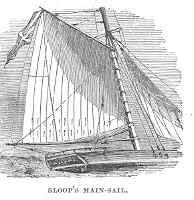

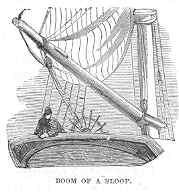

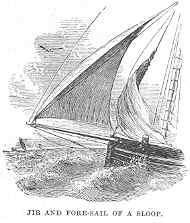

The masts, yards, and sails of a sloop are as follows:– As has been already said, one of the distinctive peculiarities of a sloop is, that it has only one mast. This mast is sometimes formed of one stick, sometimes of two; the second, or top-mast, being fastened to the top of the lower mast by cross-trees and cap, in such a way that it may be hoisted or lowered at pleasure. A sloop has usually four sails,—a mainsail, fore-sail, gaff, and jib. The main-sail is behind the lower mast. It reaches from within a few feet of the deck to the top of the lower mast, and spreads out upon two yards towards the stern or after part of the ship, over which it projects a few feet. The lower yard of the main-sail is called the boom, and the upper the main-sail yard. This is by far the largest sail in the sloop. Above it is spread the gaff, which is comparatively a small sail, and is used when the wind is not very strong. The fore-sail is a triangular sheet, which traverses on the fore-stay; that is, the strong rope which runs from the lower mast-head to the bow, or front part of the sloop. On the bowsprit is stretched the jib, another triangular sail, which reaches nearly to the top of the lower mast. The only sail that rises above the lower mast is the gaff. In stormy weather this sail is always taken down. If the wind increases to a gale, the jib is lowered and lashed to the bowsprit.

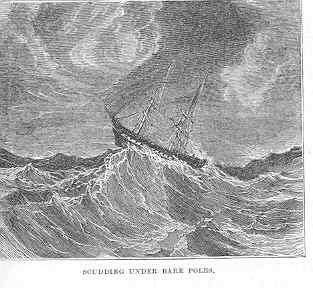

Should the gale increase, a reef is taken in the main-sail. One, two, three, and sometimes four reefs are taken in, according to the violence of the storm; when the last reef is taken in, the sloop is under close-reefed main-sail. Increased violence in the storm necessitates the taking in of the main-sail and lying-to under the fore-sail, or a part of it. Lying-to is putting the sloop’s head to the wind, and placing the helm in such a position that it tends to turn the vessel in one direction, while the gale acting on the fore-sail tends to force it in another, and thus it remains stationary between the two opposing forces. Many vessels thus lie-to, and ride out the severest storm. Sometimes, however, a dreadful hurricane arises, and compels vessels to take in all sails and “scud under bare poles”—that is, drive before the wind without any sails at all; and it is at such seasons that man is forced to feel his utter helplessness, and his absolute dependence on the Almighty. Of course, there are slight variations in the rig of sloops—some have a square-sail, and some have a flying-jib; but these are not distinctive sails, and they are seldom used in small craft.

Doubtless, those of our readers who have dwelt on the sea-coast must have observed that boats and vessels frequently sail in precisely opposite directions, although acted upon by the same wind. This apparent paradox may be explained thus:—

Suppose a vessel with the bow and stern sharp and precisely alike, so that it might sail backwards or forwards with equal facility. Suppose, also, that it has two masts exactly the same in all respects—one near the bow, the other near the stern. Suppose, further, a square sail stretched between the two masts quite flat; and remember that this would be a fore-and-aft sail—namely, one extending along the length, not across the breadth of the vessel.

Well, now, were a breeze to blow straight against the side of such a vessel, it would either blow it over, flat on its side, or urge it slowly sideways over the water, after the fashion of a crab. Now remove one of these masts—say the stern one—and erect it close to the lee-side of the vessel (that is, away from the windward-side), still keeping the sail extended. The immediate effect would be that the sail would no longer present itself flatly against the wind, but diagonally. The wind, therefore, after dashing against it would slide violently off in the direction of the mast that had been removed, that is, towards the stern. In doing so it would, of course, give the vessel a shove in the opposite direction; on the very same principle that a boy, when he jumps violently off a chair, not only sends his body in one direction, but sends the chair in the opposite direction. So, when the wind jumps off the sail towards the stern, it sends the ship in the opposite direction—namely, forward. Reverse this; bring back the mast you removed to its old place in the centre of the deck, and shift the front mast near to the lee-bulwarks. The wind will now slide off the sail towards the bow, and force our vessel in the opposite direction—namely, backward; so that, with the same side wind, two ships may sail in exactly opposite directions.

By means of the rudder, and placing the sails in various positions, so as to cause them to press against the masts in a particular manner, vessels can be made to sail not only with a side wind, but with a breeze blowing a good deal against them—in nautical phraseology, they can be made to sail “close to the wind.” In short, they can sail in every direction, except directly in the “teeth” of the wind. Some ships sail closer to the wind than others; their powers in this respect depending very much on the cut of their sails and the form of their hulls.

The Lighter is a small, rough, clumsy species of coasting-vessel, usually of the sloop rig. It is used for discharging cargoes of large vessels in harbours, and off coasts where the depth of water is not great. Lighters are usually picturesque-looking craft with dingy sails, and they seldom carry top-sails of any kind. Being seldom decked, they are more properly huge boats than little ships. But lighters are not classed according to their rig,—they may be of any rig, though that of the sloop is most commonly adopted.

The Cutter

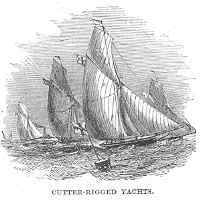

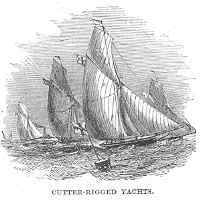

This species of vessel is similar, in nearly all respects, to the sloop; the only difference being that it is better and more elegantly built. Gentlemen’s pleasure yachts are frequently cutters; but yachts may be of any form or rig—that is, they may belong to any class of vessels without changing their name of yacht. Cutter-yachts are much more elegantly moulded and rigged than the sloops that we have just described. They are clipper-built—that is, the hull is smoothly and sharply shaped; the cut-water, in particular, is like a knife, and the bow wedge-like. In short, although similar in general outline, a cutter-yacht bears the same relation to a trading-sloop that a racer does to a cart-horse. Their sails, also, are larger in proportion, and they are fast-sailing vessels; but, on this very account, they are not such good sea-boats as their clumsy brethren, whose bluff or rounded bows rise on the waves, while the sharp vessels cut through them, and often deluge the decks with spray.

In our engraving we have several cutter-rigged yachts sailing with a light side wind, with main-sail, gaff, fore-sail, and jib set.

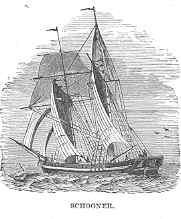

The Schooner

This is the most elegant and, for small craft, the most manageable vessel that floats. Its proportions are more agreeable to the eye than those of any other species of craft, and its rig is in favour with owners of yachts,—especially with those whose yachts are large. The schooner’s distinctive peculiarities are, that it carries two masts, which usually “rake aft,” or lean back a good deal; and its rig is chiefly fore-and-aft, like the sloop. Of the two masts, the after one is the main-mast. The other is termed the fore-mast. The sails of a schooner are—the main-sail and the gaff, on the main-mast; the fore-sail, fore-top-sail, and fore-top-gallant-sail (the two last being square sails), on the foremast. In front of the fore-mast are the staysail, the jib, and the flying-jib; these last are triangular sails. If a schooner were cut in two in the middle, cross-wise, the front portion would be in all respects a sloop with a square top-sail; the stern part would also be a sloop, minus the bowsprit and the triangular sails before the mast. Schooners sometimes carry a large square-sail, which is spread when the wind is “dead aft.” They are much used in the coasting-trade; and one of their great advantages is that they can be worked with fewer “hands” than sloops of the same size.

The BrigAdvancing step by step in our investigation of the peculiar rig and build of ships, we come to the brig. This species of craft is usually, but not necessarily, larger than those that have been described; it is generally built on a larger scale than the schooner, and often approaches in magnitude to the full-sized, three-masted ship.

The distinctive features of the brig are, that it has two masts, both of which are square-rigged. It is a particularly serviceable species of craft, and, when of large size, is much used in foreign trade.

The advantage of the square-rig over the fore-and-aft rig is, that the sails, being smaller and more numerous, are more easily managed, and require fewer men or “hands” to work them. Thus, as we increase the size of our vessel, the more necessity is there that it should be square-rigged. The huge main-sail of the sloop and schooner could not be applied to large vessels; so that when men came to construct ships of several hundred tons burden, they were compelled to increase the number of masts and sails, and diminish the size of them; hence, probably, brigs were devised after schooners. The main-mast of a brig is the aft one.

The sails are named after the masts to which they are fastened,—namely, the main-sail; above that the main-top-sail; above that the main-top-gallant-sail; and sometimes a very small sail, named the royal, is spread above all. Behind the main-sail there is a small fore-and-aft sail similar to the main-sail of a schooner, which is called the boom-main-sail. On the fore-mast is a similar sail, which is called the try-sail. Attached to the respective yards of square-rigged ships there are smaller poles or arms, which can be pushed out at pleasure, and the yard lengthened, in order to receive an additional little sailor wing on each side. These wings are called studding-sails or stun-sails, and are used only when the wind is fair and light. They are named after the sails to which they are fastened; thus there are the main-stun-sails, the main-top-stun-sails, and the main-top-gallant-stun-sails, etcetera. The fore-mast of a brig is smaller than the main-mast. It carries a fore-sail, fore-top-sail, fore-top-gallant-sail, and fore-royal. Between it and the bowsprit are the fore-stay-sail, jib, and flying-jib. The three last sails are nearly similar in all vessels. All the yards, etcetera, are hoisted and shifted, and held in their position, by a complicated arrangement of cordage, which in the mass is called the running-rigging, in contradistinction to the standing-rigging, which, as we have said, is fixed, and keeps the masts, etcetera, immovably in position. Yet every rope, in what seems to a landsman’s eye a bewildering mass of confusion, has its distinctive name and specific purpose.

Brigs and schooners, being light and handy craft, are generally used by pirates and smugglers in the prosecution of their lawless pursuits, and many a deed of bloodshed and horror has been done on board such craft by those miscreants.

The BrigantineThe rig of this vessel is a mixture of that of the sloop and brig. The brigantine is square-rigged on the fore-mast, and sloop-rigged on its after or mizzen mast. Of its two masts, the front one is the larger, and, therefore, is the main-mast. In short, a brigantine is a mixed vessel, being a brig forward and a sloop aft.

Such are our coasting-vessels; but it must be borne in mind that ships of their class are not confined to the coast. When built very large they are intended for the deep ocean trade, and many schooners approach in size to full-rigged “ships.”

Chapter Eleven.

Vessels of Large Size

We now come to speak of ships of large size, which spread an imposing cloud of canvas to the breeze, and set sail on voyages which sometimes involve the circumnavigation of the globe.

The Barque

This vessel is next in size larger than the brig. It does not follow, however, that its being larger constitutes it a barque. Some brigs are larger than barques, but generally the barque is the larger vessel. The difference between a barque and a brig is that the former has three masts, the two front ones being square-rigged, and the mizzen being fore-and-aft rigged. The centre mast is the main one. The rigging of a barque’s two front masts is almost exactly similar to the rigging of a brig, that of the mizzen is similar to a sloop. If you were to put a fore-and-aft rigged mizzen-mast into the after part of a brig, that would convert it into a barque.

The term clipper simply denotes that peculiar sharpness of build and trimness of rig which insure the greatest amount of speed, and does not specify any particular class. There are clipper sloops, clipper yachts, clipper ships, etcetera. A clipper barque, therefore, is merely a fast-sailing barque.

The peculiar characteristics of the clipper build are, knife-like sharpness of the cut-water and bow, and exceeding correctness of cut in the sails, so that these may be drawn as tight and flat as possible. Too much bulge in a sail is a disadvantage in the way of sailing. Indeed, flatness is so important a desideratum, that experimentalists have more than once applied sails made of thin planks of wood to their clippers; but we do not know that this has turned out to be much of an improvement. The masts of all clippers, except those of the sloop or cutter rig, generally rake aft a good deal—that is, they lean backwards; a position which is supposed to tend to increase speed. Merchant vessels are seldom of the clipper build, because the sharpness of this peculiar formation diminishes the available space for cargo very much.

The ShipThe largest class of vessel that floats upon the sea is the full-rigged ship, the distinctive peculiarity of which is, that its three masts are all square-rigged together, with the addition of one or two fore-and-aft sails.

As the fore and main masts of a “ship” are exactly similar to those of a barque, which have been already described, we shall content ourself with remarking that the mizzen-mast is similar in nearly all respects to the other two, except that it is smaller. The sails upon it are—the spanker (a fore-and-aft sail projecting over the quarter-deck), the mizzen-top-sail and mizzen-top-gallant-sail, both of which are square sails. Above all these a “ship” sometimes puts up small square-sails called the royals; and, above these, sky-sails.

Chapter Twelve.

Wooden and Iron Walls

The birth of the British Navy may be said to have taken place in the reign of King Alfred. That great and good king, whose wisdom and foresight were only equalled by his valour, had a fleet of upwards of one hundred ships. With these he fought the Danes to the death, not always successfully, not always even holding his own; for the Danes at this early period of their history were a hardy race of sea-warriors, not less skilful than courageous. But to King Alfred, with his beaked, oared war-ships, is undoubtedly due the merit of having laid the foundation of England’s maritime ascendency.