Полная версия

Полная версияMan on the Ocean: A Book about Boats and Ships

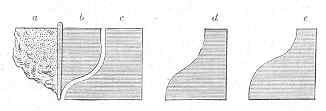

Figure 1 will keep you right in regard to relative length and depth; Figure 2 in regard to shape of stern and bulge of the sides; Figure 3 secures correct form of the bow; and Figure 4 enables you to proportion the breadth to the length.

The next thing to be done is to procure a block of fir-wood, with as few knots in it as possible, and straight in the grain. The size is a matter of choice—any size from a foot to eighteen inches will do very well for a model boat. Before beginning to carve this, it should be planed quite smooth and even on all sides, and the ends cut perfectly square, to permit of the requisite pencil-drawings being made on it.

The tools required are a small tenon-saw, a chisel, two or three gouges of different sizes, a spoke-shave, and a file with one side flat and the other round. A rough rasp-file and a pair of compasses will also be found useful. All of these ought to be exceedingly sharp. The gouges and the spoke-shave will be found the most useful of these implements.

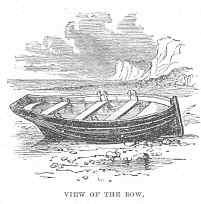

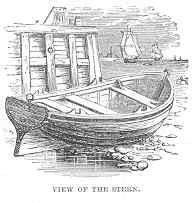

Begin by drawing a straight line with pencil down the exact centre of what will be the deck; continue it down the part that will be the stern; then carry it along the bottom of the block, where the keel will be, and up the front part, or bow. If this line has been correctly drawn, the end of it will exactly meet the place where you began to draw it. On the correctness of this line much will depend; therefore it is necessary to be careful and precise in finding out the centre of each surface of the block with the compasses. Next, draw a line on each side of this centre line (as in the accompanying diagram), which will give the thickness of the keel and stern-post. Then on the upper surface of the block draw the form of the boat to correspond with the bird’s-eye view (Figure 4, on page 82) already referred to. Then draw one-half of the stern on a piece of thin card-board, and when satisfied that it is correct cut it out with scissors; apply it to the model, first on one side, and then on the other side of the stern-post. By thus using a pattern of only one-half of the stern, exact uniformity of the two sides is secured. Treat the bow in the same way. Of course the pattern of the bow will at first be drawn on the flat surface of the block, and it will represent not the actual bow, but the thickest part of the hull, as seen in the position of Figure 3, on page 82. After this, turn the side of the block, and draw the form represented in Figure 1, page 82, thereon, and mark on the keel the point where the stem and keel join, and also where the stern and keel join. This is necessary, because in carving the sides of the boat these lines will be among the first to be cut away. The next proceeding is to cut away at the sides and bottom of the block until, looking at it in the proper positions, the bow resembles Figure 3, and the stern Figure 2, above referred to. This will be done chiefly with the gouge, the chisel and spoke-shave being reserved for finishing. Then saw off the parts of the bow and stern that will give the requisite slope to these parts, being guided by the marks made on the keel. In cutting away the upper parts of the bow and stern, be guided by the curved lines on the deck; and in forming the lower parts of the same portions, keep your eye on your drawing, which is represented by Figure 1.

It is advisable to finish one side of the boat first, so that, by measurement and comparison, the other side may be made exactly similar. Those who wish to be very particular on this point may secure almost exact uniformity of the two sides by cutting out several moulds (three will be sufficient) in card-board. These moulds must be cut so as to fit three marked points on the finished side, as represented by three dotted lines on Figure 1; and then the unfinished side must be cut so as to fit the moulds at the corresponding points. If the two sides are quite equal at these three points, it is almost impossible to go far wrong in cutting away the wood between them—the eye will be a sufficient guide for the rest.

The accompanying diagram shows the three moulds referred to, one of them being nearly applied to the finished part of the hull to which it belongs. Thus—(a) represents the unfinished side of the boat; (b) the finished side; (c) is the mould or card cut to correspond with the widest part of the finished side, near the centre of the boat; (d) is the mould for the part near the bow; (e) for that near the stern. These drawings are roughly given, to indicate the plan on which you should proceed. The exact forms will depend on your own taste or fancy, as formed by the variously-shaped boats you have studied. And it may be remarked here, that all we have said in regard to the cutting out of model boats applies equally to model ships.

The outside of your boat having been finished, the bow having been fashioned somewhat like that represented in the accompanying cut, and the stern having been shaped like that shown in the illustration given below, the next thing to be done is to hollow out the hull. Care must be taken in doing this not to cut away too much wood from one part, or to leave too much at another; a little more than half an inch of thickness may be left everywhere. Next, fix in the thwarts, or seats, as in the foregoing cut, attach a leaden keel, and the boat is completed.

The keel may be formed by running melted lead into a groove cut in a piece of wood, or, better still, into a groove made in nearly dry clay. By driving four or five nails (well greased) into the groove before pouring in the melted lead, holes may be formed in the keel by simply withdrawing the nails after it is cold.

A mast and sail, however, are still wanted. The best kind of sail is the lug, which is an elongated square sail—shown in the accompanying illustration.

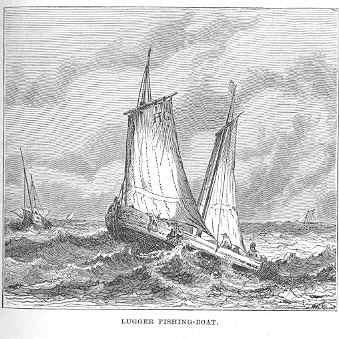

Most of our fishing-boats are provided with lug-sails, and on this account are styled luggers. These boats are of all sizes, some of them being fifty tons burden, and carrying crews of seven or ten men each. A picture of a lugger is given on the next page.

Great numbers of fishing-boats may be seen at Great Yarmouth, and all along the coasts of Norfolk and Suffolk. They are employed in the herring-fishery, and use nets, which are let down in deep water, corks floating the upper edges of the nets, and the lower edges being sunk by leads, so that they remain in the water perpendicularly like walls, and intercept the shoals of herring when they chance to pass. Thousands of these glittering silvery fish get entangled in the meshes during night. Then the nets are drawn up, and the fish taken out and thrown into a “well,” whence they are removed as quickly as possible, and salted and packed in lockers; while the nets are let down again into the sea. These boats remain out usually a week at a time. Most of them return to port on Saturday, in order to spend Sunday as a day of rest. Some, however—regardless of the fact that He who gives them the fish with such liberal hand, also gave them the command, “Remember the sabbath day”—continue to prosecute the fishing on that day. But many a good man among the fishermen has borne testimony to the fact that these do not gain additional wealth by their act of disobedience; while they lose in the matter of nets (which suffer from want of frequent drying) and in the matter of health (which cannot be maintained so well without a weekly day of rest), while there can be no doubt that they lose the inestimable blessing of a good conscience. So true is it that godliness is profitable for the life which now is as well as for that which is to come.

A model boat should be rigged with only one mast and lug-sail, or with two masts and sails at the most. Three are unnecessary and cumbrous. Each sail should be fixed to a yard, which should be hoisted or hauled down by means of a block or pulley fastened near the top of the mast. The positions of these yards and the form of the sails may be more easily understood by a glance at our woodcut than by reading many pages of description.

Sprit-sails are sometimes used in boats. These are fore-and-aft sails, which are kept distended by a sprit instead of a yard. The sprit is a long pole, one end of which is fixed to the lowest innermost corner, near the mast, and the other end extending to the highest outermost corner; thus it lies diagonally across the sail. It is convenient when a boat “tacks,” or “goes about”—in other words, when it goes round frequently, and sails, now leaning on one side, and, at the next tack, on the other side. In this case the sprit requires little shifting or attention. But it is dangerous in squally weather, because, although the sheet or line which holds the lower and outer end of a sail may be let go for the sake of safety, the upper part remains spread to the wind because of the sprit.

The best rig of all for a model boat, and indeed for a pleasure-boat, is that which comprises a main-sail, in form like that of a sloop or a cutter, omitting the boom, or lower yard, and a triangular fore-sail extending from near the mast to the bow of the boat or to the end of the bowsprit—somewhat like a sloop’s jib. Both of the sails referred to may be seen at the part of this book which treats of sloops and cutters; and they are the same in form, with but slight modification, when applied to boats.

Racing-boats are long, low, narrow, and light. Some are so narrow as to require iron rowlocks extending a considerable distance beyond the sides of the boat for the oars to rest in. Many of these light craft may be seen on the Thames and Clyde, and other rivers throughout the kingdom. The larger sort do not require what we may call the outrigger rowlocks.

The “Rob Roy” canoe has, of late years, come much into fashion as a racing and pleasure boat. Whatever the advantages of this craft may be, it has this disadvantage, that it can hold only one person; so that it may be styled an unsocial craft, the company of one or more friends being impossible, unless, indeed, one or more canoes travel in company.

This species of canoe became celebrated some years ago, in consequence of an interesting and adventurous voyage of a thousand miles through Germany, Switzerland, and France, and, subsequently, through part of Norway and Sweden, made by Mr Macgregor in a craft of this kind, to which he gave the name of “Rob Roy.” Since the craft became popular, numerous and important improvements have been made in the construction of its hull and several parts, but its distinctive features remain unaltered. The “Rob Roy” canoe is, in fact, almost identical with the Eskimo kayak, except in regard to the material of which it is made—the former being composed wholly of wood, the latter of a framework of wood covered with skin. There is the same long, low, fish-like form, the same deck, almost on a level with the water, the same hole in the centre for the admission of the man, the same apron to keep out water, and the same long, double-bladed paddle, which is dipped on each side alternately. The “Rob Roy” has, however, the addition of a small mast, a lug-sail, and a jib. It has also a back-board, to support the back of the canoeman; the paddle, too, is somewhat shorter than that of the Eskimo canoe; and the whole affair is smarter, and more in accordance with the tastes and habits of the civilised men who use it.

In his various voyages, which we might almost style journeys, the originator of the “Rob Roy” canoe proved conclusively that there were few earthly objects which could form a barrier to his progress. When his canoe could not carry him, he carried it! Waterfalls could not stop him, because he landed below them, and carried his canoe and small amount of baggage to the smooth water above the falls. In this he followed the example of the fur-traders and Indians of North America, who travel over any number of miles of wilderness in this manner. Shallows could not stop him, because his little bark drew only a few inches of water. Turbulent water could not swamp him, because the waves washed harmlessly over his smooth deck, and circled innocently round his protective apron. Even long stretches of dry land could not stop him, because barrows, or carts, or railways could transport his canoe hither and thither with perfect ease to any distance; so that when the waters of one river failed him, those of the next nearest were easily made available. In conclusion, it may be said that the “Rob Roy” canoe is a most useful and pleasant craft for boys and young men, especially at those watering-places which have no harbour or pier, and where, in consequence of the flatness of the beach, boats cannot easily be used.

It would be an almost endless as well as unprofitable task to go over the names and characteristics of all our various kinds of boats in detail.

Of heavy-sterned and clumsy river craft, we have an innumerable fleet.

There are also Torbay Trawlers, which are cutters of from twenty to fifty tons; and the herring-boats of Scotland; and cobbles, which are broad, bluff, little boats; and barges, which are broad, bluff, large ones; and skiffs, and scows, and many others.

In foreign lands many curious boats are to be met with. The most graceful of them, perhaps, are those which carry lateen sails—enormous triangular sails, of which kind each boat usually carries only one.

India-rubber boats there are, which can be inflated with a pair of bellows, and, when full, can support half-a-dozen men or more, while, when empty, they can be rolled up and carried on the back of one man, or in a barrow. One boat of this kind we once saw and paddled in. It was made in the form of a cloak, and could be carried quite easily on one’s shoulders. When inflated, it formed a sort of oval canoe, which was quite capable of supporting one person. We speak from experience, having tried it some years ago on the Serpentine, and found it to be extremely buoyant, but a little given to spin round at each stroke of the paddle, owing to its circular shape and want of cut-water or keel.

Of all the boats that swim, the lifeboat is certainly one of the most interesting; perhaps it is not too much to add that it is also one of the most useful. But this boat deserves a chapter to itself.

Chapter Seven.

Lifeboats and Lightships

When our noble Lifeboat Institution was in its infancy, a deed was performed by a young woman which at once illustrates the extreme danger to which those who attempt to rescue the shipwrecked must expose themselves, and the great need there was, thirty years ago, for some better provision than existed at that time for the defence of our extensive sea-board against the dire consequences of storm and wreck. It is not, we think, inappropriate to begin our chapter on lifeboats with a brief account of the heroic deed of:—

Grace DarlingThere are not many women who, like Joan of Arc, put forth their hands to the work peculiarly belonging to the male sex, and achieve for themselves undying fame. And among these there are very few indeed who, in thus quitting their natural sphere and assuming masculine duties, retain their feminine modesty and gentleness.

Such a one, however, was Grace Darling. She did not, indeed, altogether quit her station and follow a course peculiar to the male sex; but she did once seize the oar and launch fearlessly upon the raging sea, and perform a deed which strong and daring men might have been proud of—which drew forth the wondering admiration of her country, and has rendered her name indissolubly connected with the annals of heroic daring in the saving of human life from vessels wrecked upon our rock-bound shores.

Grace Darling was born in November 1815, at Bamborough, on the Northumberland coast. Her father was keeper of the lighthouse on the Longstone, one of the Farne Islands lying off that coast; and here, on a mere bit of rock surrounded by the ocean, and often by the howling tempests and the foaming breakers of that dangerous spot, our heroine spent the greater part of her life, cut off almost totally from the joys and pursuits of the busy world. She and her mother managed the domestic economy of the lighthouse on the little islet, while her father trimmed the lantern that sent a blaze of friendly light to warn mariners off that dangerous coast.

In personal appearance Grace Darling is described as having been fair and comely, with a gentle, modest expression of countenance; about the middle size; and with nothing in the least degree masculine about her. She had reached her twenty-second year when the wreck took place in connection with which her name has become famous.

The Farne Islands are peculiarly dangerous. The sea rushes with tremendous force between the smaller islands, and, despite the warning light, wrecks occasionally take place among them. In days of old, when men had neither heart nor head to erect lighthouses for the protection of their fellows, many a noble ship must have been dashed to pieces there, and many an awful shriek must have mingled with the hoarse roar of the surf round these rent and weatherworn rocks.

A gentleman who visited the Longstone rock in 1838, describes it thus:—

“It was, like the rest of these desolate isles, all of dark whinstone, cracked in every direction, and worn with the action of winds, waves, and tempests since the world began. Over the greater part of it was not a blade of grass, nor a grain of earth; it was bare and iron-like stone, crusted, round all the coast as far as high-water mark, with limpet and still smaller shells. We ascended wrinkled hills of black stone, and descended into worn and dismal dells of the same; into some of which, where the tide got entrance, it came pouring and roaring in raging whiteness, and churning the loose fragments of whinstone into round pebbles, and piling them up in deep crevices with seaweeds, like great round ropes and heaps of fucus. Over our heads screamed hundreds of hovering birds, the gull mingling its hideous laughter most wildly.”

One wild and stormy night in September 1838—such a night as induces those on land to draw closer round the fire, and offer up, perchance, a silent prayer for those who are at sea—a steamer was battling, at disadvantage with the billows, off Saint Abb’s Head. She was the Forfarshire, a steamer of three hundred tons, under command of Mr John Humble; and had started from Hull for Dundee with a valuable cargo, a crew of twenty-one men, and forty-one passengers.

It was a fearful night. The storm raged furiously, and would have tried the qualities of even a stout vessel; but this one was in very bad repair, and her boilers were in such a state that the engines soon became entirely useless, and at last they ceased to work. We cannot conceive the danger of a steamer left thus comparatively helpless in a furious storm and dark night off a dangerous coast.

In a short time the vessel became quite unmanageable, and drifted with the direction of the tide, no one knew whither. Soon the terrible cry arose, “Breakers to leeward,” and immediately after the Farne lights became visible. A despairing attempt was now made by the captain to run the ship between the islands and the mainland; but in this he failed, and about three o’clock she struck heavily on a rock bow foremost.

The scene of consternation that followed is indescribable. Immediately one of the boats was lowered, and with a freight of terror-stricken people pushed off, but not before one or two persons had fallen into the sea and perished in their vain attempts to get into it. This party in the boat, nine in number, survived the storm of that awful night, and were picked up the following morning by a Montrose sloop. Of those left in the ill-fated ship some remained in the after-part; a few stationed themselves near the bow, thinking it the safest spot. The captain stood helpless, his wife clinging to him, while several other females gave vent to their agony of despair in fearful cries.

Meanwhile the waves dashed the vessel again and again on the rock, and at last a larger billow than the rest lifted her up and let her fall down upon its sharp edge. The effect was tremendous and instantaneous; the vessel was literally broken in two pieces, and the after-part, with the greater number of the passengers in the cabin, was swept away through the Fifa Gut, a tremendous current which is considered dangerous even in good weather. Among those who thus perished were the captain and his wife. The forepart of the steamer, with the few who had happily taken refuge upon it, remained fast on the rock. Here eight or nine of the passengers and crew clung to the windlass, and a woman named Sarah Dawson, with her two little children, lay huddled together in a corner of the fore-cabin, exposed to the fury of winds and waves all the remainder of that dreadful night. For hours each returning wave carried a thrill of terror to their hearts; for the shattered wreck reeled before every shock, and it seemed as if it would certainly be swept away into the churning foam before daybreak.

But daylight came at last, and the survivors on the wreck began to sweep the dim horizon with straining eyeballs as a faint hope at last began to arise in their bosoms. Nor were these trembling hopes doomed to disappointment. At the eleventh hour God in his mercy sent deliverance. Through the glimmering dawn and the driving spray the lighthouse-keeper’s daughter from the lonely watch-tower descried the wreck, which was about a mile distant from the Longstone. From the mainland, too, they were observed; and crowds of people lined the shore and gazed upon the distant speck, to which, by the aid of telescopes, the survivors were seen clinging with the tenacity of despair.

But no boat could live in that raging sea, which still lashed madly against the riven rocks, although the violence of the storm had begun to abate. An offer of 5 pounds by the steward of Bamborough Castle failed to tempt a crew of men to launch their boat. One daring heart and willing hand was there, however. Grace Darling, fired with an intense desire to save the perishing ones, urged her father to launch their little boat. At first he held back. There was no one at the lighthouse except himself, his wife, and his daughter. What could such a crew do in a little open boat in so wild a sea? He knew the extreme peril they should encounter better than his daughter, and very naturally hesitated to run so great a risk. For, besides the danger of swamping, and the comparatively weak arm of an inexperienced woman at the oar, the passage from the Longstone to the wreck could only be accomplished with the ebb-tide; so that unless the exhausted survivors should prove to be able to lend their aid, they could not pull back again to the lighthouse.

But the earnest importunities of the heroic girl were not to be resisted. Her father at last consented, and the little boat pushed off with the man and the young woman for its crew. It may be imagined with what a thrill of joy and hope the people on the wreck beheld the boat dancing an the crested waves towards them; and how great must have been the surprise that mingled with their other feelings on observing that one of the rowers was a woman!

They gained the rock in safety; but here their danger was increased ten-fold, and it was only by the exertion of great muscular power, coupled with resolute courage, that they prevented the boat being dashed to pieces against the rock.

One by one the sufferers were got into the boat. Sarah Dawson was found lying in the fore-cabin with a spark of life still trembling in her bosom, and she still clasped her two little ones in her arms, but the spirits of both had fled to Him who gave them. With great difficulty the boat was rowed back to the Longstone, and the rescued crew landed in safety. Here, owing to the violence of the sea, they were detained for nearly three days, along with a boat’s crew which had put off to their relief from North Sunderland; and it required some ingenuity to accommodate so large a party within the narrow limits of a lighthouse. Grace gave up her bed to poor Mrs Dawson; most of the others rested as they best could upon the floor.