Полная версия

Полная версияBattles with the Sea

When, however, life does not require to be saved, and when opportunity offers, it allows its boats to save property.

It saves—and rewards those who assist in saving—many hundreds of lives every year. Last year (1882) the number saved by lifeboats was 741, besides 143 lives saved by shore-boats and other means, for which rewards were given by the Institution; making a grand total of 884 lives saved in that one year. The number each year is often larger, seldom less. One year (1869) the rescued lives amounted to the grand number of 1231, and in the greater number of cases the rescues were effected in circumstances in which ordinary boats would have been utterly useless—worse than useless, for they would have drowned their crews. In respect of this matter the value of the lifeboat to the nation cannot be estimated—at least, not until we invent some sort of spiritual arithmetic whereby we may calculate the price of widows’ and orphans’ tears, and of broken hearts!

But in regard to more material things it is possible to speak definitely.

It frequently happens in stormy weather that vessels show signals of distress, either because they are so badly strained as to be in a sinking condition, or so damaged that they are unmanageable, or the crews have become so exhausted as to be no longer capable of working for their own preservation. In all such cases the lifeboat puts off with the intention in the first instance of saving life. It reaches the vessel in distress; some of the boat’s crew spring on board, and find, perhaps, that there is some hope of saving the ship. Knowing the locality well, they steer her clear of rocks and shoals. Being comparatively fresh and vigorous, they work the pumps with a will, manage to keep her afloat, and finally steer her into port, thus saving ship and cargo as well as crew.

Now let me impress on you that incidents of this sort are not of rare occurrence. There is no play of fancy in my statements; they happen every year. Last year (1882) twenty-three vessels were thus saved by lifeboat crews. Another year thirty-three, another year fifty-three, ships were thus saved. As surely and regularly as the year comes round, so surely and regularly are ships and property saved by lifeboats—saved to the nation! It cannot be too forcibly pointed out that a wrecked ship is not only an individual, but a national loss. Insurance protects the individual, but insurance cannot, in the nature of things, protect the nation. If you drop a thousand sovereigns in the street, that is a loss to you, but not to the nation; some lucky individual will find the money and circulate it. But if you drop it into the sea, it is lost not only to you, but to the nation, indeed to the world itself, for ever,—of course taking for granted that our amphibious divers don’t fish it up again!

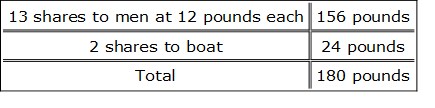

Well, let us gauge the value of our lifeboats in this light. If a lifeboat saves a ship worth ten or twenty thousand sovereigns from destruction, it presents that sum literally as a free gift to owners and nation. A free gift, I repeat, because lifeboats are provided solely to save life—not property. Saving the latter is, therefore, extraneous service. Of course it would be too much to expect our gallant boatmen to volunteer to work the lifeboats, in the worst of weather, at the imminent risk of their lives, unless they were also allowed an occasional chance of earning salvage. Accordingly, when they save a ship worth, say 20,000 pounds, they are entitled to put in a claim on the owners for 200 pounds salvage. This sum would be divided (after deducting all expenses, such as payments to helpers, hire of horses, etcetera) between the men and the boat. Thus—deduct, say, 20 pounds expenses leaves 180 pounds to divide into fifteen shares; the crew numbering thirteen men:—

Let us now consider the value of loaded ships.

Not very long ago a large Spanish ship was saved by one of our lifeboats. She had grounded on a bank off the south coast of Ireland. The captain and crew forsook her and escaped to land in their boats. One man, however, was inadvertently left on board. Soon after, the wind shifted; the ship slipped off the bank into deep water, and drifted to the northward. Her doom appeared to be fixed, but the crew of the Cahore lifeboat observed her, launched their boat, and, after a long pull against wind and sea, boarded the ship and found her with seven feet of water in the hold. The duty of the boat’s crew was to save the Spanish sailor, but they did more, they worked the pumps and trimmed the sails and saved the ship as well, and handed her over to an agent for the owners. This vessel and cargo was valued at 20,000 pounds.

Now observe, in passing, that this Cahore lifeboat not only did much good, but received considerable and well-merited benefit, each man receiving 34 pounds from the grateful owners, who also presented 68 pounds to the Institution, in consideration of the risk of damage incurred to their boat. No doubt it may be objected that this, being a foreign ship, was not saved to our nation; but, as the proverb says, “It is not lost what a friend gets,” and I think it is very satisfactory to reflect that we presented the handsome sum of 20,000 pounds to Spain as a free gift on that occasion.

This was a saved ship. Let us look now at a lost one. Some years ago a ship named the Golden Age was lost. It was well named though ill-fated, for the value of that ship and cargo was 200,000 pounds. The cost of a lifeboat with equipment and transporting carriage complete is about 650 pounds, and there are 273 lifeboats at present on the shores of the United Kingdom. Here is material for a calculation! If that single ship had been among the twenty-seven saved last year (and it might have been) the sum thus rescued from the sea would have been sufficient to pay for all the lifeboats in the kingdom, and leave 22,550 pounds in hand! But it was not among the saved. It was lost—a dead loss to Great Britain. So was the Ontario of Liverpool, wrecked in October, 1864, and valued at 100,000 pounds. Also the Assage, wrecked on the Irish coast, and valued at 200,000 pounds. Here are five hundred thousand pounds—half a million of money—lost by the wreck of these three ships alone. Of course, these three are selected as specimens of the most valuable vessels lost among the two thousand wrecks that take place each year on our coasts; they vary from a first-rate mail steamer to a coal coffin, but set them down at any figure you please, and it will still remain true that it would be worth our while to keep up our lifeboat fleet, for the mere chance of saving such valuable property.

But after all is said that can be said on this point, the subject sinks into insignificance when contrasted with the lifeboat’s true work—the saving of human lives.

There is yet another and still higher sense in which the lifeboat is of immense value to the nation. I refer to the moral influence it exercises among us. If many hundreds of lives are annually saved by our lifeboat fleet, does it not follow, as a necessary consequence, that happiness and gratitude must affect thousands of hearts in a way that cannot fail to redound to the glory of God, as well as the good of man? Let facts answer this question.

We cannot of course, intrude on the privacy of human hearts and tell what goes on there, but there are a few outward symptoms that are generally accepted as pretty fair tests of spiritual condition. One of these is parting with money! Looking at the matter in this light, the records of the Institution show that thousands of men, women, and children, are beneficially influenced by the lifeboat cause.

The highest contributor to its funds in the land is our Queen; the lowliest a sailor’s orphan child. Here are a few of the gifts to the Institution, culled almost at random from the Reports. One gentleman leaves it a legacy of 10,000 pounds. Some time ago a sum of 5000 pounds was sent anonymously by “a friend.” A hundred pounds comes in as a second donation from “a sailor’s daughter.” Fifty pounds come from a British admiral, and five shillings from “the savings of a child!” One-and-sixpence is sent by another child in postage-stamps, and 1 pound 5 shillings as the collection of a Sunday school in Manchester; 15 pounds from three fellow-servants; 10 pounds from a shipwrecked pilot, and 10 shillings, 6 pence from an “old salt.” I myself had once the pleasure of receiving twopence for the lifeboat cause from an exceedingly poor but enthusiastic old woman! But my most interesting experience in this way was the receipt of a note written by a blind boy—well and legibly written, too—telling me that he had raised the sum of 100 pounds for the Lifeboat Institution.

And this beneficial influence of our lifeboat service travels far beyond our own shores. Here is evidence of that. Finland sends 50 pounds to our Institution to testify its appreciation of the good done by us to its sailors. President Lincoln, of the United States, when involved in all the anxieties of the great war between North and South, found time to send 100 pounds to the Institution in acknowledgment of services rendered to American ships in distress. Russia and Holland send naval men to inspect—not our armaments and materiel of hateful war, but—our lifeboat management! France, in generous emulation, starts a Lifeboat Institution of its own, and sends over to ask our society to supply it with boats—and, last, but not least, it has been said that foreigners, driven far out of their course and stranded, soon come to know that they have been wrecked on the British coast, by the persevering efforts that are made to save their lives!

And now, good reader, let me urge this subject on your earnest consideration. Surely every one should be ready to lend a hand to rescue the perishing! One would think it almost superfluous to say more. So it would be, if there were none who required the line of duty and privilege to be pointed out to them. But I fear that many, especially dwellers in the interior of our land, are not sufficiently alive to the claims that the lifeboat has upon them.

Let me illustrate this by a case or two—imaginary cases, I admit, but none the less illustrative on that account.

“Mother,” says a little boy, with flashing eyes and curly flaxen hair; “I want to go to sea!”

He has been reading “Cook’s Voyages” and “Robinson Crusoe,” and looks wistfully out upon the small pond in front of his home, which is the biggest “bit of water” his eyes have ever seen, for he dwells among the cornfields and pastures of the interior of the land.

“Don’t think of it, darling Willie. You might get wrecked,—perhaps drowned.”

But “darling Willie” does think of it, and asserts that being wrecked is the very thing he wants, and that he’s willing to take his chance of being drowned! And Willie goes on thinking of it, year after year, until he gains his point, and becomes the family’s “sailor boy,” and mayhap, for the first time in her life, Willie’s mother casts more than a passing glance at newspaper records of lifeboat work. But she does no more. She has not yet been awakened. “The people of the coast naturally look after the things of the coast,” has been her sentiment on the subject—if she has had any definite sentiments about it at all.

On returning from his first voyage Willie’s ship is wrecked. On a horrible night, in the howling tempest, with his flaxen curls tossed about, his hands convulsively clutching the shrouds of the topmast, and the hissing billows leaping up as if they wished to lick him off his refuge on the cross-trees, Willie awakens to the dread reality about which he had dreamed when reading Cook and Crusoe. Next morning a lady with livid face, and eyes glaring at a newspaper, gasps, “Willie’s ship—is—wrecked! five lost—thirteen saved by the lifeboat.” One faint gleam of hope! “Willie may be among the thirteen!” Minutes, that seem hours, of agony ensue; then a telegram arrives, “Saved, Mother—thank God,—by the lifeboat.”

“Ay, thank God,” echoes Willie’s mother, with the profoundest emotion and sincerity she ever felt; but think you, reader, that she did no more? Did she pass languidly over the records of lifeboat work after that day? Did she leave the management and support of lifeboats to the people of the coast? I trow not. But what difference had the saving of Willie made in the lifeboat cause? Was hers the only Willie in the wide World? Are we to act on so selfish a principle, as that we shall decline to take an interest in an admittedly grand and good and national cause, until our eyes are forcibly opened by “our Willie” being in danger? Of course I address myself to people who have really kind and sympathetic hearts, but who, from one cause or another, have not yet had this subject earnestly submitted to their consideration. To those who have no heart to consider the woes and necessities of suffering humanity, I have nothing whatever to say,—except,—God help them!

Let me enforce this plea—that inland cities and towns and villages should support the Lifeboat Institution—with another imaginary case.

A tremendous gale is blowing from the south-east, sleet driving like needles—enough, almost, to put your eyes out. A “good ship,” under close-reefed topsails, is bearing up for port after a prosperous voyage, but the air is so thick with drift that they cannot make out the guiding lights. She strikes and sticks fast on outlying sands, where the sea is roaring and leaping like a thousand fiends in the wintry blast. There are passengers on board from the Antipodes, with boxes and bags of gold-dust, the result of years of toil at the diggings. They do not realise the full significance of the catastrophe. No wonder—they are landsmen! The tide chances to be low at the time; as it rises, they awake to the dread reality. Billows burst over them like miniature Niagaras. The good ship which has for many weeks breasted the waves so gallantly, and seemed so solid and so strong, is treated like a cork, and becomes apparently an egg-shell!

Night comes—darkness increasing the awful aspect of the situation tenfold. What are boxes and bags of gold-dust now—now that wild despair has seized them all, excepting those who, through God’s grace, have learned to “fear no evil?”

Suddenly, through darkness, spray, and hurly-burly thick, a ghostly boat is seen! The lifeboat! Well do the seamen know its form! A cheer arouses sinking hearts, and hope once more revives. The work of rescuing is vigorously, violently, almost fiercely begun. The merest child might see that the motto of the lifeboat-men is “Victory or death.” But it cannot be done as quickly as they desire; the rolling of the wreck, the mad plunging and sheering of the boat, prevent that.

A sturdy middle-aged man named Brown—a common name, frequently associated with common sense—is having a rope fastened round his waist by one of the lifeboat crew named Jones—also a common name, not seldom associated with uncommon courage. But Brown must wait a few minutes while his wife is being lowered into the boat.

“Oh! be careful. Do it gently, there’s a good fellow,” roars Brown, in terrible anxiety, as he sees her swung off.

“Never fear, sir; she’s all right,” says Jones, with a quiet reassuring smile, for Jones is a tough old hand, accustomed to such scenes.

Mrs Brown misses the boat, and dips into the raging sea.

“Gone!” gasps Brown, struggling to free himself from Jones and leap after her, but the grasp of Jones is too much for him.

“Hold on, sir? she’s all right, sir, bless you; they’ll have her on board in a minute.”

“I’ve got bags, boxes, bucketfuls of gold in the hold,” roars Brown. “Only save her, and it’s all yours!”

The shrieking blast will not allow even his strong voice to reach the men in the lifeboat, but they need no such inducement to work.

“The gold won’t be yours long,” remarks Jones, with another smile. Neptune’ll have it all to-night. See! they’ve got her into the boat all right, sir. Now don’t struggle so; you’ll get down to her in a minute. There’s another lady to go before your turn comes.

During these few moments of forced inaction the self-possessed Jones remarks to Brown, in order to quiet him, that they’ll be all saved in half an hour, and asks if he lives near that part of the coast.

“Live near it!” gasps Brown. “No! I live nowhere. Bin five years at the diggings. Made a fortune. Going to live with the old folk now—at Blunderton, far away from the sea; high up among the mountains.”

“Hm!” grunts Jones. “Do they help to float the lifeboats at Blunderton?”

“The lifeboats? No, of course not; never think of lifeboats up there.”

“Some of you think of ’em down here, though,” remarks Jones. “Do you help the cause in any way, sir?”

“Me? No. Never gave a shilling to it.”

“Well, never mind. It’s your turn now, sir. Come along. We’ll save you. Jump!” cries Jones.

And they do save him, and all on board of that ill-fated ship, with as much heartfelt satisfaction as if the rescued ones had each been a contributor of a thousand a year to the lifeboat cause.

“Don’t forget us, sir, when you gits home,” whispers Jones to Brown at parting.

And does Brown forget him? Nay, verily! He goes home to Blunderton, stirs up the people, hires the town-hall, gets the chief magistrate to take the chair, and forms a Branch of the Royal National Lifeboat Institution—the Blunderton Branch, which, ever afterwards, honourably bears its annual share in the expense, and in the privilege, of rescuing men, women, and little ones from the raging seas. Moreover, Brown becomes the enthusiastic secretary of the Branch. And here let me remark that no society of this nature can hope to succeed, unless its secretary be an enthusiast.

Now, reader, if you think I have made out a good case, let me entreat you to go, with Brown in your eye, “and do likewise.”

And don’t fancy that I am advising you to attempt the impossible. The supposed Blunderton case is founded on fact. During a lecturing tour one man—somewhat enthusiastic in the lifeboat cause—preached the propriety of inland towns starting Branches of the Lifeboat Institution. Upwards of half a dozen such towns responded to the exhortation, and, from that date, have continued to be annual contributors and sympathisers.

Chapter Seven.

The Life-Saving Rocket

We shall now turn from the lifeboat to our other great engine of war with which we do battle with the sea from year to year, namely, the Rocket Apparatus.

This engine, however, is in the hands of Government, and is managed by the coastguard. And it may be remarked here, in reference to coastguard men, that they render constant and effective aid in the saving of shipwrecked crews. At least one-third of the medals awarded by the Lifeboat Institution go to the men of the coastguard.

Every one has heard of Captain Manby’s mortar. Its object is to effect communication between a stranded ship and the shore by means of a rope attached to a shot, which is fired over the former. The same end is now more easily attained by a rocket with a light rope, or line, attached to it.

Now the rocket apparatus is a little complicated, and ignorance in regard to the manner of using it has been the cause of some loss of life. Many people think that if a rope can only be conveyed from a stranded ship to the shore, the saving of the crew is comparatively a sure and easy matter. This is a mistake. If a rope—a stout cable—were fixed between a wreck and the shore, say at a distance of three or four hundred yards, it is obvious that only a few of the strongest men could clamber along it. Even these, if benumbed and exhausted—as is frequently the case in shipwreck—could not accomplish the feat. But let us suppose, still further, that the vessel rolls from side to side, dipping the rope in the sea and jerking it out again at each roll, what man could make the attempt with much hope of success, and what, in such circumstances, would become of women and children?

More than one rope must be fixed between ship and shore, if the work of saving life is to be done efficiently. Accordingly, in the rocket apparatus there are four distinct portions of tackle. First the rocket-line; second, the whip; third, the hawser; and, fourth, the lifebuoy—sometimes called the sling-lifebuoy, and sometimes the breeches-buoy.

The rocket-line is that which is first thrown over the wreck by the rocket. It is small and light, and of considerable length—the extreme distance to which a rocket may carry it in the teeth of a gale being between three and four hundred yards.

The whip is a thicker line, rove through a block or pulley, and having its two ends spliced together without a knot, in such a manner that the join does not check the running of the rope through the pulley. Thus the whip becomes a double line—a sort of continuous rope, or, as it is called, an “endless fall,” by means of which the lifebuoy is passed to and fro between the wreck and shore.

The hawser is a thick rope, or cable, to which the lifebuoy is suspended when in action.

The lifebuoy is one of those circular lifebuoys—with which most of us are familiar—which hang at the sides of steamers and other vessels, to be ready in case of any one falling overboard. It has, however, the addition of a pair of huge canvas breeches attached to it, to prevent those who are being rescued from slipping through.

Let us suppose, now, that a wreck is on the shore at a part where the coast is rugged and steep, the beach very narrow, and the water so deep that it has been driven on the rocks not more than a couple of hundred yards from the cliffs. The beach is so rocky that no lifeboat would dare to approach, or, if she did venture, she would be speedily dashed to pieces—for a lifeboat is not absolutely invulnerable! The coastguardsmen are on the alert. They had followed the vessel with anxious looks for hours that day as she struggled right gallantly to weather the headland and make the harbour. When they saw her miss stays on the last tack and drift shoreward, they knew her doom was fixed; hurried off for the rocket-cart; ran it down to the narrow strip of pebbly beach below the cliffs, and now they are fixing up the shore part of the apparatus. The chief part of this consists of the rocket-stand and the box in which the line is coiled, in a peculiar and scarcely describable manner, that permits of its flying out with great freedom.

While thus engaged they hear the crashing of the vessel’s timbers as the great waves hurl or grind her against the hungry rocks. They also hear the cries of agonised men and women rising even above the howling storm, and hasten their operations.

At last all is ready. The rocket, a large one made of iron, is placed in its stand, a stick and the line are attached to it, a careful aim is taken, and fire applied. Amid a blaze and burst of smoke the rocket leaps from its position, and rushes out to sea with a furious persistency that even the storm-fiend himself is powerless to arrest. But he can baffle it to some extent—sufficient allowance has not been made for the force and direction of the wind. The rocket flies, indeed, beyond the wreck, but drops into the sea, a little to the left of her.

“Another—look alive!” is the sharp order. Again the fiery messenger of mercy leaps forth, and this time with success. The line drops over the wreck and catches in the rigging. And at this point comes into play, sometimes, that ignorance to which I have referred—culpable ignorance, for surely every captain who sails upon the sea ought to have intimate acquaintance with the details of the life-saving apparatus of every nation. Yet, so it is, that some crews, after receiving the rocket-line, have not known what to do with it, and have even perished with the means of deliverance in their grasp. In one case several men of a crew tied themselves together with the end of the line and leaped into the sea! They were indeed hauled ashore, but I believe that most, if not all, of them were drowned.

Those whom we are now rescuing, however, are gifted, let us suppose, with a small share of common sense. Having got hold of the line, one of the crew, separated from the rest, signals the fact to the shore by waving a hat, handkerchief, or flag, if it be day. At night a light is shown over the ship’s side for a short time, and then concealed. This being done, those on shore make the end of the line fast to the whip with its “tailed-block” and signal to haul off the line. When the whip is got on board, a tally, or piece of wood, is seen with white letters on a black ground painted on it. On one side the words are English—on the other French. One of the crew reads eagerly:—