Полная версия:

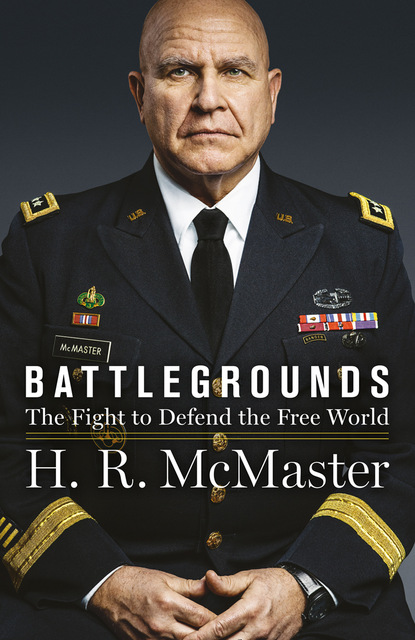

Battlegrounds

By 2017, it was clear that Russia was pursuing an aggressive strategy to subvert the United States and other Western democracies. Russian cyber attacks and information warfare campaigns directed against European elections and the 2016 U.S. presidential election were just one part of a multifaceted effort to exploit rifts in European and American society through propaganda, disinformation, and political subversion. As social media began to polarize the United States and other Western societies and pit communities against each other, Russian agents conducted cyber attacks and released sensitive information. Although Russian leaders routinely denied responsibility, the Kremlin was reportedly directing a sophisticated campaign.1 Russia also used cyber attacks and malicious cyber intrusions to create vulnerabilities in critical infrastructure, such as in the energy sector. For example, by early 2018, the United States knew that Russia had conducted the NotPetya cyber attack that first infected Ukraine’s government agencies, energy companies, metro systems, and banks.2 It spread later to Europe, Asia, and the Americas, costing ten billion dollars in losses and damages around the world.3

Having studied the evolution of Russia new-generation warfare (RNGW) for years, I looked forward to talking with Patrushev to understand better the motivations behind this pernicious form of aggression that combined military, political, economic, cyber, and informational means. The day after our meeting with Patrushev, I gave a speech at the Munich Security Conference pledging that “the United States will expose and act against those who use cyberspace, social media, and other means to advance campaigns of disinformation, subversion and espionage.” During my year as national security advisor, we had worked hard to impose costs on Russia. I hoped to convince Patrushev of the dangers associated with Russia’s continued implementation of a strategy that pushed our two nations along a path toward worsening relations and potential conflict.

The potential for conflict with Russia was growing. The civil war in Syria was a particular concern. In March 2019, Russian general Valery Gerasimov cited the Syrian Civil War as a successful example of Russian intervention to “defend and advance national interests beyond the borders of Russia.”4 The war was a humanitarian catastrophe. Russia had supported the Syrian regime of Bashar al-Assad since the beginning of the conflict in 2011. In August 2013, the Syrian regime used poison gas to kill more than fourteen hundred innocent civilians, including hundreds of children, but it was not its first use of chemical weapons, nor would it be the last. From December 2012 to August 2014, the Syrian regime used them against civilians at least fourteen times. Despite President Barack Obama’s declaration in 2012 that the use of these heinous weapons to murder civilians was a red line, the United States did not respond. President Putin likely concluded that America would not react to aggression. By the end of spring 2014, an emboldened Putin had annexed Crimea and invaded Eastern Ukraine. And then, in September 2015, Russia intervened directly in the Syrian Civil War to save Assad’s murderous regime. After another massacre with nerve agents at Khan Shaykhun in April 2017, President Trump ordered the U.S. military to strike Syrian facilities and aircraft with fifty-nine cruise missiles.5 By 2018, Russian-supported forces fighting for Assad’s regime were converging with American-supported forces fighting the terrorist group ISIS. When I met Patrushev, the danger of a direct clash between Russians and Americans on the ground in Syria was not only more likely—it had already happened.6

On February 7, 2018, the week prior to the Geneva meeting, Russian mercenaries and other pro-Assad forces reinforced with tanks and artillery attacked U.S. forces and the Kurdish and Arab militiamen they were advising, in northeastern Syria. The mercenaries were from the company owned by Yevgeny Prigozhin, a Russian oligarch known as “Putin’s cook,” a man indicted by U.S. Special Counsel Robert Mueller and sanctioned by the Trump administration for his role in sowing disinformation during the 2016 U.S. presidential election.7 It was an ill-conceived and poorly executed attack. U.S. forces and their Syrian Democratic Forces partners killed more than two hundred Russian mercenaries while suffering no casualties.8 Eager to suppress negative news prior to the forthcoming presidential election, the Kremlin lied about the number of casualties suffered. Putin wanted to win the election by the widest possible margin. News of a costly defeat brought on by Russia’s need to finance reconstruction of a country it had helped destroy would not help achieve this. The ultimate purpose of the Russian-led attack was to seize control of an old Conoco oil plant that promised to generate revenue and defray the costs of the war and reconstruction. No battle like that between Russians and Americans had ever occurred, even during the height of the Cold War.

A year had passed since Patrushev suggested we meet. I had delayed in deference to Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, who wanted to make a personal assessment of Russia’s intentions first. Tillerson had hoped that his preexisting relationship with President Putin and Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov, which he developed as chief executive officer of ExxonMobil, might deliver some improvement in U.S.-Russian relations. He wanted to offer Putin an “off ramp” in Ukraine and Syria based on the assumption that those interventions, including U.S. and European economic sanctions imposed on Russia, might entice Lavrov to negotiate an eventual Russian withdrawal. In Lavrov’s case, it was not clear that he could deliver even if the possibility for improved relations existed.

Lavrov’s approach to foreign policy was old-Soviet style, reflexively anti-Western and suspicious of new initiatives. Lavrov invariably accused the United States and the West of instigating the 2003 Rose Revolution in Georgia, the 2004 Orange Revolution in Ukraine, and the 2005 Tulip Revolution in Kyrgyzstan, as well as large-scale protests in Russia in 2011. It seemed that Lavrov had neither the independence of mind to come up with solutions nor the latitude to make basic decisions. By early 2018, it was clear that Tillerson’s valiant efforts to find areas of cooperation with Russia had foundered. It was past time to establish a direct channel of communication between the White House and the Kremlin, other than the occasional phone calls and meetings between Trump and Putin. Since Putin had centralized power in an unprecedented way, even for a country with a long history of authoritarianism, it was important to have a relationship with someone close to Putin himself. Patrushev, Putin’s right-hand man, who occupied a position that is the Russian equivalent of national security advisor, was the ideal candidate.9

No one on our team believed that the Geneva meeting would solve our problems with Russia. Events of the following month confirmed that belief. Soon after our meeting, Russia used a banned nerve agent in an attempted murder of a former intelligence official in Salisbury, United Kingdom, and Putin made a chest-thumping speech in which he announced new nuclear weapons. We hoped, however, that this new channel of communication between the White House and the Kremlin might lay a foundation for some bilateral diplomatic, military, and intelligence engagement with Russia across both governments. Discussions between the U.S. National Security Council staff and the Secretariat of the Security Council of Russia had existed under prior administrations. We could foster a common understanding of each nation’s interests and an awareness of where those interests diverged or converged. The two countries might then manage their differences and find some areas for cooperation. Mapping our interests might be a first step toward avoiding costly competitions or dangerous confrontations like the recent clash in Syria. At the very least, we might prepare more fully for the president’s meetings with Putin to secure favorable outcomes.

I traveled with Dr. Fiona Hill, the National Security Council’s senior director for Europe and Russia, and Mr. Joe Wang, director for Russia. During our long flight on the “big blue plane,” as we referred to the air force Boeing 757, we discussed Vladimir Putin, Russian policy, and the man whom I would soon meet, Nikolai Patrushev. Fiona is one of the foremost experts on Russia under Putin. In her book Mr. Putin, coauthored with Clifford Gaddy, she observed that “Putin thinks, plans, and acts strategically.” She also observed, however, that “for Putin, strategic planning is contingency planning. There is no step-by-step blueprint.” Our other travel companion, Joe, a bright young State Department civil service officer of ten years, judged that prospects for a near-term improvement in U.S.-Russian relations were dim mainly due to Mr. Putin’s need for an external foe to prevent internal opposition. This need to direct the Russian people’s attention away from internal problems drove an increasingly aggressive foreign policy, while the need to generate support for that foreign policy amplified rhetoric designed to conjure the external enemy as a menace. In his March 2018 speech announcing new nuclear weapons, Putin even showed “automated videos depicting” nuclear warheads descending toward the state of Florida.

On the plane, I recalled what I knew about Patrushev. He and Putin had a lot in common. Both entered the KGB in the 1970s. Patrushev succeeded Putin as director of the FSB from 1999 to 2008. Putin, Patrushev, and other prominent former KGB officers who moved into influential Kremlin positions after the 2000 Russian presidential elections believed that they were the ultimate patriots. Putin trusted and relied on Patrushev. Both men understood that, especially in Russia, knowledge is power. Their base of knowledge allowed them to form a protection racket that propelled Putin to the pinnacle of power and kept him there for more than two decades. The future Russian president’s climb began in the late 1990s, when he was head of the GKU, the government’s inspectorate charged with uncovering fraud and corruption in government and federal agencies. He used that position to build dossiers on Russian oligarchs, powerful businessmen who had accumulated great wealth during the era of Russian privatization in the 1990s. He detailed their finances and business transactions. Putin had dirt on everyone. Because the rule of law had broken down in Russia, the oligarchs regarded him as an arbiter whose persuasive power derived from holding them hostage. Putin prevented infighting that might have collapsed the corrupt system and crushed all of them. When he became the head of the FSB in July 1998, he named Patrushev as head of a new Directorate of Economic Security. He and Patrushev then used their skills as KGB case officers to collect and monopolize information. In exchange for respecting the oligarchs’ property and allowing them to amass wealth, Putin expected them to act as his agents, use their business activity to promote Russian interests abroad, and comply with direction from him, their case officer, and protector.10

Fiona, Joe, and I landed in Geneva in the early morning of February 16, 2018. Ted Allegra, an experienced diplomat and gracious host who was the chargé d’affaires ad interim of the U.S. Mission in Geneva, greeted us. We held an informative video telephone conference with the U.S. ambassador to Russia, Jon Huntsman. Huntsman, a wise statesman, politician, and businessman who had served previously as governor of Utah, U.S. ambassador to Singapore, and, most recently, U.S. ambassador to China, worked daily in a difficult and hostile environment. The ambassador was supportive of the Patrushev meeting and the opening of a channel between Patrushev’s Secretariat and the NSC staff. He described how Russian harassment of embassy officials had intensified in recent months. But he took a long view of U.S.-Russian relations and felt that we should lay the groundwork for improved relations. I met Mr. Patrushev outside the U.S. consulate. As he exited the limousine, he evinced the self-assurance one might expect from an old KGB official. Two of his senior staff, a deputy secretary of his Security Council and a senior aide responsible for the U.S.-Russia relationship, along with a staff officer serving as a note taker, accompanied him.

After introductions, I offered coffee to the Patrushev delegation—none of them touched the light refreshments we had on hand—and we sat down across from one another. I welcomed the delegation and, after mentioning my interest in Russian history and literature, reviewed the purpose of the meeting and the sustained dialogue that was meant to follow it: to develop mutual understanding of our interests. I asked Mr. Patrushev to begin. He spoke for the better part of an hour. His version of the Kremlin’s view of the world revolved around three main points. First, he portrayed Russia’s annexation of Crimea and invasion of Ukraine as defensive efforts to protect ethnic Russian populations from what he described as Ukrainian far-right extremists and U.S. and European attempts to engineer a pro-European Union and, therefore, an anti-Russian government in Kiev. Second, he described the expansion of NATO countries and the rotation of NATO forces into areas that Russia considered traditional spheres of influence as threatening. Third, he argued that the United States, its allies, and its partners had increased the terrorist threat across the greater Middle East through ill-conceived interventions in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Libya.11 Finally, perhaps in anticipation of my comments, he flatly denied attacking the 2016 U.S. presidential election or attempting to subvert Western democracies. None of what Patrushev said was surprising, and I did not want to waste time rebutting his assertions or denials. Instead, I endeavored to elevate the discussion to generate mutual understanding of our vital interests in four areas.

First, I noted that both our countries were interested in the prevention of a direct military conflict. Russia’s annexation of Crimea and invasion of eastern Ukraine was particularly dangerous to peace, not only because it was the first time since World War II that borders within Europe were changed by force, but also because Russia’s continued use of unconventional forces in Ukraine or elsewhere in Europe could escalate.12 One of the historical parallels to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine was Austria-Hungary’s invasion of Serbia in 1914, which triggered World War I. World War I was a powerful analogy because it was a war in which none of the participants would have engaged had they known the price they would pay in treasure and, especially, blood. Many people wanted war, but no one got the war he or she wanted. Moscow and Washington both needed to acknowledge the risk that the next Russian attempt might trigger a military confrontation, even if Russia intended to act below the threshold of what might elicit a military response from NATO. I wanted Patrushev to see the U.S. and European Union sanctions on Russia for invading Ukraine and annexing Crimea as more than punitive; they were meant to deter Russia from future actions that could lead to a destructive war. I thought that Patrushev might agree that we were in a dangerous, transitional period. Communicating the United States’ vital interests and our determination to counter Russian aggression would disabuse Kremlin leaders of any belief that they could exploit perceived American complacency and wage new-generation warfare without risk.

I also wanted Patrushev to understand that the United States was awake to the danger of Putin’s playbook and, in particular, RNGW. Russia’s actions in Crimea and Ukraine were analogous to a long-standing Russian military strategy known as maskirovka, or the use of tactical deception and disguise. Like maskirovka, Putin’s playbook combined disinformation with deniability. The new playbook added disruptive technologies and the use of cyberspace to enable conventional and unconventional military forces. And, where possible, the Kremlin fostered economic dependencies to coerce weak states and deter a response to aggression. The parallels to previous dangerous periods, not only in the nineteenth but particularly in the twentieth century, were striking. In recent years, Russia had acted aggressively, counting on American complacency based on the self-delusion that great power competition was a relic of the past. Consider Secretary of State John Kerry’s comments: “You just don’t in the twenty-first century behave in nineteenth-century fashion by invading another country on completely trumped-up pretext.”13 I thought it important to let Patrushev know that we were prepared to compete and would no longer be absent from the arena.

Second, both our nations sought to preserve our sovereignty or the ability to shape our relationships abroad and govern ourselves at home. Russia’s sustained campaign of disinformation, propaganda, and political subversion was a direct threat to our sovereignty and that of our allies. I suggested that it was in the Kremlin’s interest to stop this activity because Russian actions would unite Americans and other Western societies against Russia. Their recent efforts to influence election outcomes had failed or backfired. For example, Russian disinformation aimed against Emmanuel Macron in France during the 2017 presidential election increased support for the candidate and probably helped Macron win the presidency. Another example of Russia’s heavy-handed tactics backfiring was the failed October 2016 coup in Montenegro that intended to prevent that country’s accession to NATO. Russia’s meddling actually accelerated Montenegro’s admission to NATO and its application for membership in the European Union. Finally, Russian efforts to convince the Trump administration to lift economic sanctions in 2017 failed as the administration instead sanctioned more than one hundred individuals and companies in response to Russia’s continued occupation of Crimea and aggression in Eastern Ukraine. More sanctions would follow under the Global Magnitsky Human Rights Accountability Act.14 During my conversation with Patrushev, I joked that Russia’s efforts to divide Americans and meddle in our election made the imposition of severe sanctions on Russia the only subject that united Congress. In fact, the first major foreign policy legislation to emerge from the U.S. Congress after President Trump took office was a sanctions bill on Russia, the Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act, which passed in the Senate in a 98–2 vote after flying through the House by a 419–3 margin.15 At this, Patrushev cracked a smile, perhaps to acknowledge that we both were very much aware of Russia’s subversive activities.

Third, both nations must protect our people from jihadist terrorist organizations. That is why it did not seem to be in Russia’s long-term interests to provide weapons to the Taliban in Afghanistan or to spread disinformation that the United States supported terrorist groups. Such actions strengthened organizations that posed a common threat to both our countries. Moreover, Russia’s support for Iran, Iran’s proxy militias, and Bashar al-Assad’s forces in their brutal campaign in Syria not only perpetuated the humanitarian and refugee crisis, but also fueled a broader sectarian conflict that strengthened jihadist terrorists like ISIS and Al-Qaeda. These terrorist organizations draw strength from the fear that Iranian-backed Shia militias generate among Sunni communities, allowing them to portray themselves as patrons and protectors of those communities. I hoped that Patrushev might see that Russia’s support for Iran only reinforced jihadist terrorist recruitment and support among Sunni Muslim populations.

Finally, I raised the subject of how Russia seemed to act reflexively against the United States even when cooperation was in its interests. I used the case of Russia’s circumvention of UN sanctions against North Korea as an example. In addition to the direct threat of North Korean nuclear missiles to Russia itself, a nuclear-armed North Korea might lead other neighboring countries like Japan to conclude that they needed their own nuclear weapons. Moreover, North Korea had never developed a weapon that it did not try to sell. It had already tried to help Syria develop an Iranian-financed nuclear program in an effort that was only thwarted by a September 2007 Israeli strike on the nuclear reactor under construction near Dayr al-Zawr, Syria. Ten North Korean scientists were reportedly killed in the strike.16 What if North Korea sold nuclear weapons to terrorist organizations? What nation would be safe?

Patrushev listened but showed no discernible reaction. After a break, we agreed to charge our teams with mapping our interests and preparing materials for presentation to Presidents Trump and Putin in advance of their next meeting. I departed Geneva convinced of the importance of our work. I realized, however, that relations were unlikely to improve due to Putin’s motivations, his objectives, and the strategy he was pursuing.

When he assumed the presidency at the turn of the century, Putin worked to strengthen the system that had put him there. His overarching goal was to restore Russia’s status as a great power. He would be patient, estimating that Russia would need fifteen years to build strength before it was ready to challenge the West.17 Indeed, approximately fifteen years later, he annexed Crimea, invaded Ukraine, and intervened in the Syrian Civil War.

OUR EFFORT to map Russian and U.S. interests as a way of managing our relationship addressed only one dimension of the challenge before us. That is because Putin, Patrushev, and their colleagues in the Kremlin are motivated as much by emotion as by calculations of interest. As the Athenian historian and general Thucydides concluded twenty-five hundred years ago, conflict is driven by fear and honor as well as interest.18 President Putin and those, like Patrushev, whom he brought with him into the Kremlin were shaken by the collapse of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (aka USSR, aka Soviet Union) and feared the possibility of a “color revolution” in Russia. They were proud men whose sense of honor had been insulted by the West’s victory in the Cold War and whose livelihoods depended on the Soviet system. Putin described the breakup of the empire and the end of Soviet rule in Russia as “a major geopolitical disaster of the century,” one that not only was a “genuine drama” for those who suddenly found themselves outside Russia, but also caused problems that “infected Russia itself.”19 The breakup resulted in the loss of half of the former Soviet population and almost a quarter of its territory. At the height of Soviet dominance, Russian influence extended as far west in Europe as East Berlin. Since the USSR’s collapse, Russia had lost control of nearly all of Eastern Europe. Ethnic Russians were scattered across the newly independent successor states of the USSR, such as Ukraine, Georgia, and Estonia. Russians who remember Soviet greatness, including Putin, Patrushev, and their KGB colleagues, watched as their former vassal states, unshackled from Communist authoritarian control, liberalized and eagerly joined other free and open societies under the European Union and North Atlantic Treaty Organization.

The Soviet Union had a truly global reach, penetrating into Asia, Africa, and Latin America. Throughout Communist states, Russians were often looked up to as big brothers in an ideological war—or at least that was how many Russians imagined their Communist brethren viewed them. But then men like Putin and Patrushev saw their mighty empire, one of two global superpowers, fall to the status of a struggling regional power—and it stung. Once Putin achieved the presidency, he set about restoring Russia’s lost grandeur, a process that is still under way. Above all, Putin fears an internal threat to the kleptocratic political order he has built with the oligarchs and his cronies in the KGB. To allay fear and restore honor, he has consolidated his base of power internally and gone on the offensive against Europe and the United States.

By the time Putin became president, the cheerfulness associated with the prospect of transforming post-Soviet Russia into a successful state with a booming economy had given way to gloom. In the 1990s, Russian efforts to transition to a market economy proved unable to overcome the complete collapse of the Communist system. Greedy apparatchiks, members of the Soviet bureaucratic political apparatus, were empowered in the wake of that collapse. Because market reforms threatened their grip on power, Russian politicians led a backlash against free-market reformers. The failure to either establish an adequate legal framework or to eliminate Soviet-era bureaucracy made the transition to a market economy even more difficult. The final straw was the financial crisis of 1998, when the Russian ruble lost two thirds of its value. The failure of market reforms and the rise of the oligarchs created a system that was not only fragile, but also ideal for Putin and those who retained political control through the post-Soviet transition to consolidate their power. As journalist (and later Canadian foreign minister) Chrystia Freeland observed, Russia was “an ex-KGB officer’s paradise.” Under Boris Yeltsin’s government, the Siloviki (hard-line functionaries of the Soviet-era Ministry of the Interior, the Soviet Army, and the KGB) comprised only 4 percent of the government. Under Putin, it grew to 58.3 percent. Fear of losing control as the post-Soviet economy and social structure were collapsing propelled the Siloviki into power. And Putin, Patrushev, and their Siloviki colleagues wanted Russia to be feared again.20