Полная версия:

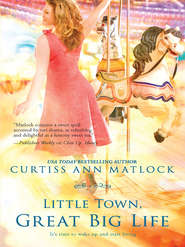

Little Town, Great Big Life

Oran gazed at the pills in her hand as if he didn’t know what they were, but then he took them. Handing her back the glass of water, he gave her a crooked grin.

As Belinda returned behind the soda fountain counter, a voice hollered out for service over at the pharmacy. She was relieved to see Oran’s lanky body rise and hear him answer in an exaggerated drawl, “Keep your shirt on. This ain’t New York City.”

“Was Fayrene hurt bad?” asked Iris MacCoy, who was waiting on an order of half a dozen barbecue sandwiches and the same number of fountain drinks to take back to MacCoy Feed and Grain.

“No, ma’am,” said Arlo, passing over two sizable cardboard carry containers. “I put in extra bags of potato chips.”

Arlo’s gaze lingered on Iris’s chest, which was where most men’s eyes lingered. Iris was a stunning woman. Belinda knew that Iris was over fifty years of age, and had more refurbishment on her than a 1960 Corvette.

“Well, I saw the whole thing,” said Julia Jenkins-Tinsley, scooting her small frame up on a stool, sitting half on and half off. Julia was postmistress and a woman who lived life in perpetual motion.

“I had just come out of the P.O. on my way down here. The car didn’t hit her—Fayrene hit it. She ran right out in the street. She had her hood up to protect her hairdo—you know how she is about her hair. She was no more lookin’ where she was goin’ than the man in the moon. She never is, and is always crossin’ in the middle of the block. Maybe this will teach her a lesson. We have crosswalks for a reason. Here’s your mail.”

Julia passed a wad of mail held by a rubber band across the counter to Belinda. “I saw you hadn’t come by your box yet today. I know you are just swamped here with your mother on vacation. Thought you might want to see you got another postcard from her, but she didn’t really say anything. Just that she’s havin’ a good time, and what she writes every time—Love to Valentine.”

Iris said, “That pavement is really slick from the rain. We haven’t had any all winter, and now it’s just dangerous out there. I about slipped comin’ in here. And, Belinda, I just love your reports from your mother. Please tell her I’m missin’ her.”

At this, Belinda gave a polite nod.

Iris gave her and then everyone else at the soda fountain a feminine little wave as she left. The eyes of the three men followed her, and old Norman Cooper, of all people, jumped up and ran after her, saying, “Let me help you get all that to your car, Iris.”

Belinda found the postcard. It was an aerial photograph of Paris, France. She took it over and stuck it on the bulletin board, below the previous two, one from New York City, another from London.

Julia, looking up at the menu on the wall as if she had not seen it every day of her adult life, finally said, “I guess I’ll have a chicken salad on lettuce, no bread, and a sweet tea with lemon—two slices. I can do the sugar. I jogged an extra mile this mornin’. Make it to go. I need to get back. Norris didn’t come in today.”

As Belinda turned to get the order, she noted that Julia’s gaze dropped to her hips with a distinctive disapproving look. Julia went at keeping in shape as if it would give her a ticket to heaven.

Belinda knew that she had something Julia would never have: six years of youth, womanly breasts and total guilt-free eating of anything she wanted.

“Did you see that guy who picked up Fayrene and carried her back to the café?” Julia asked.

“I saw him, but I haven’t heard who he is. Jaydee said he thought maybe the guy missed the bus to Dallas…that he saw him earlier in the café. Lucky for Fayrene.” She glanced over to the pharmacy, where Oran was waiting on Imperia Brown, who had all three of her children down with the flu.

Julia said, “No…he’s some guy Woody brought into the café this mornin’. Where Woody met him, nobody seems to know, and Woody won’t say. You know how he can be—that inscrutable old wise black man routine.”

Belinda, closing the plastic container of chicken salad and resisting licking her finger, asked if the stranger had a name.

Julia eagerly filled in with all she knew. The man’s name was Andy Smith, and he had a very cool British-type accent but was from Australia. Bingo Yardell had asked him. Bingo had also asked what had brought him to town, but he had been distracted working the counter and had not answered. “He knows how to brew a proper cup of tea. Bingo Yardell was in there havin’ breakfast this mornin’, when this woman came in off the Dallas bus and ordered a cup of hot tea. She made a big deal out of the café needin’ to have china teapots, not those little metal deals. I have thought that, too, ever since Juice and I went to New York for his grocers’ convention and stayed on the concierge floor. Every mornin’ the hotel served a layout, and they had tea in china pots. It really does make all the difference. And this Andy fella was able to make the woman a proper cup of tea.”

Belinda set the woman’s foam cup of cold tea on the counter. “I doubt there’s a large call for hot tea over at the café.”

“That’s what Fayrene said, but Carly said she serves it right often to customers over there in the cold months—mornin’s like this one was, a cup of hot tea is nice. Tea has a lot of anti-oxidants.” The postmistress put her mouth to the straw and sucked deeply, as if eager to get antioxidants that very moment.

“It’s got somethin’ everyone likes.” Belinda cast an eye to the cold-tea pitcher. All the talk was making her want some.

“Well…” Julia laid the exact change on the counter and picked up her lunch. “I gotta get back. I’ll be listenin’ to your report this afternoon. I like to hear about your mother’s trip. Be sure to tell her to keep writin’ home…and tell her to write somethin’ interestin’ on the postcards.”

“Wait a minute, and I’ll give you her e-mail address so you can write her yourself.”

“Oh, Lordy, I don’t mess with that e-mail. I work for the U.S. Postal Service. You just tell her for me, ’kay?” The woman went out the door.

Belinda said under her breath, “I don’t have another blessed thing better to do than send messages from ever’body and their cousin to my mother.”

Nadine called with an excuse again. Her voice, as usual, came so faintly over the telephone that Belinda strained to hear.

“I’m sorry I missed the lunch hour, Miz Belinda. I had a flat tire.”

“I really need you tomorrow, Nadine,” Belinda said with a sternness that she hoped would motivate. She could fire the young woman, but a replacement was likely to be worse.

As she wiped up the counters and appliances, she heard in memory her mother’s voice: I am so tired of this store, you can just shoot me now.

Belinda had never believed her mother when she said this. It had always seemed that the store was her mother’s life. Both her parents had seemed happier at the store than anywhere else. It had been at home with family that all the problems went on.

Belinda, too, loved the store, and had for the past couple of years wanted her mother to turn over the full running of it to her. Be careful what you ask for.

She would have bitten her tongue off before admitting it, but after ten days of running it alone, she was thinking, I am so tired of this store, you can just shoot me now.

Belinda tossed her apron on the stool and headed for the storage room, where she found Arlo sitting, as she had known he would be, on a box, reading a comic book. He didn’t bother to jump up, simply cast her a questioning expression. She told him to go take care of the soda fountain and that he needed to slice another lemon. Then she called him back and gave him the comic book he had laid aside.

Following him out of the storage room, she went to her office, which was nothing more than a partitioned area sandwiched between the back door and the restrooms. She had it fixed up nicely, though, framed art on the walls, and the most stylish in desks and computer setups—although the very day her mother had left for Europe, she’d had Arlo exchange her modern desk for her mother’s old heavy one. This was the desk that had belonged to Belinda’s father, and, before that, the two uncles who had founded the drugstore.

Now the desk belonged to her, Belinda thought, sitting herself behind it. At least until her mother returned.

The radio was already on from that morning. She turned the volume up slightly and pulled her carefully typed notes in front of her.

Each Wednesday, Belinda did a radio advertising spot for Blaine’s Drugstore called About Town and Beyond, in which she told all the social news and light gossip, and ended with a health or fashion tip. The following Sunday, the same piece she gave over the radio would appear in print in the Valentine Voice.

Even Belinda, who was not easily surprised, was amazed at the things people would tell out of the great desire to hear their name on the radio or see it in the newspaper. It was curious that these same people would readily talk about the intimate details of a relationship to all and sundry, but would not for love nor money mention trouble with constipation. Speaking publically of sex was acceptable and speaking of constipation considered dirty. What a world.

Jim Rainwater’s voice announcing her upcoming spot came over the airwaves, followed by an advertisement for the Ford dealership out on the highway. Belinda opened the desk drawer to get a piece of gum.

Her eye fell on her mother’s package of cigarillos.

She hated it when her mother smoked them. But now Belinda quite deliberately pulled out one of the narrow little cigars. She searched back in the drawer, finding a box of matches. She put the cigarillo between her lips, struck the match on the box and lit the tobacco, puffing expertly.

Belinda had smoked for a couple of years in her early twenties. She was one of those few very fortunate souls who did not get addicted. One time a cousin had done a study of the family and found that not one Blaine woman could ever be said to have had an addiction of any sort, excepting having the last word.

The cigarillo’s pungent taste caused a few coughs, but she took another puff and blew out a good stream of smoke. She could see what her mother saw in smoking one of these.

Just then the telephone on her desk rang. Jim Rainwater said, “Ten seconds.”

She brought her notes in front of her, turned off the radio and took one more good puff. Through the telephone receiver came the drugstore’s theme music and Jim Rainwater’s voice. “This week’s About Town and Beyond, with Belinda Blaine of Blaine’s Drugstore and Soda Fountain, your hometown store.”

“Good afternoon, ever’one.” Her voice was a little husky from the cigarillo. She liked it.

“This week over here at Blaine’s hometown drugstore we have fifteen percent off all Ecco Bella natural cosmetics, a buy-one-get-one-free special on vitamin C for those late-winter colds and a superspecial of buy two little travel packets of aspirin and get a third free. Many of you may remember—my daddy used to say that there was no better a remedy than aspirin.

“Now, for our Around Town news. Willie Lee Holloway and his dog, Munro, took the title of Best in Show the past Saturday at the Women’s Auxiliary Annual Community Dog Show, for the fourth straight year! I won’t say who said it, but there was at least one jealous whiner who said Munro should step down.

“Munro, honey, you just go on competing as long as you are able. Don’t let people who are jealous hinder you.

“And now, I’m sorry to give the news to the ladies, but our favorite UPS man, Buddy Wyatt, has become engaged. The fiancée’s name is Krystal Lynn Howard, and she is manager at McDonald’s on the turnpike and also attends junior college as a business major. The wedding is tentatively planned for late September.

“Ummmm…” For a moment, she found herself distracted by the cigarillo, for which she had no ashtray. “I want to assure everyone that Fayrene Gardner, who ran into a car this morning while crossin’ Main Street in the middle of the block, only got a scraped knee, praise God. She was well tended by Blaine’s own druggist and paramedic, Oran Lackey.

“Now, for Beyond. For those of you who may have been dead and escaped hearing, my mother is vacationin’ in Europe, along with Lillian Jennings. Here is her latest letter home:

“Bonjour, mes amis,”

(A number of listeners were a little awed at Belinda’s fluid pronunciation of the French; Belinda frequently watched a foreign language show on PBS.)

“We arrived yesterday afternoon at our destination at last. Things are different over here. I saw armed military at the airport. I’m talking machine guns…or whatever they are called these days. I could not decide if I felt more secure or worried that I might at any moment be gunned down. People are very friendly, though.

“My daughter Margaret did us proud—this place is as beautiful as she had promised. We are about fifteen minutes from Nice. That is Neece for those of you who may not know. It is on the Riviera, playground for the rich and famous. Oh, at the airport, Lillian thought she saw Frank Sinatra, but I kind of doubt it. How would we even recognize him at his age? Is he dead yet?

“The weather is real nice in Nice, slept under blankets but already getting warm today.

“Au revoir,

“Love, Vella Blaine, who does not wish anyone was here.

“That’s it from Mama…. Now, I want to speak a plain word about constipation. Don’t turn the dial. Ladies, regular eliminations of body waste is the best beautifier for complexion, hair and attitude. Increase your energy and your sexual stamina, too, by getting yourself regular. Come see me down here at Blaine’s Drugstore, and I’ll fix you up with some natural remedies. There is just no need to suffer.

“That’s it from Blaine’s Drugstore, providing the best of the old and the new, and we will always beat the big discount drugstores on price. Back to you, Jim.”

“Thank you, Miss Belinda,” she heard him say just as she clicked off, and in a tone that made her think he was red as a beet.

She saw she had dropped ash on the desk and remembered why she disliked smoking. It was just dirty. With relief, she found an ashtray in the rear of the center drawer, then relaxed back in the chair for a couple more puffs, since she did have it lit.

“You look like Aunt Vella, sittin’ there.” Arlo’s head poked around the partition.

“I presume you didn’t abandon the cash register just to make that observation.” She vigorously tamped the cigarillo into the ashtray.

“Huh?” He looked confused.

“What did you want?”

“Oh. Yeah…Inez Cooper is out here at the herbs and vitamins. She wants to know if there’s somethin’ she could slip her husband to make him stop smokin’.”

“Tell her I’ll be right there.” She tossed the package of cigarillos into the trash can, followed by the ashtray.

Passing the soda fountain counter, she told Arlo, “Soon as you get a chance, I want you to switch the desks back around. Put Mama’s desk back in her place, and move mine back into my office.”

She could tell she had confused him again.

CHAPTER 4

The Great Compromise

AFTER TWO DAYS OF TATE GOING BACK AND FORTH across the street between the houses of the two old neighbors and using all his negotiating skills, the matter was settled. Winston and Everett would share hosting of the new Wake Up show for an hour each morning. This could be managed mostly because Willie Lee would join them. Willie Lee’s presence always encouraged people to be on their best behavior.

Corrine stood with her aunt Marilee in the yellow light on the front porch. Each with a baby on the hip, and each disgusted about the early hour.

“You all come right back after the show and get a proper breakfast,” said Aunt Marilee. “And don’t go eatin’ a bunch of doughnuts. Remember your cholesterol, Tate…your sugar, Winston. Don’t you make Willie Lee late for school.”

Corrine, ever vigilant over her younger cousin, put in, “Somebody tie Willie Lee’s shoestring.”

To which Willie Lee hollered back, “I ca-n do it!”

Willie Lee and Winston exchanged looks. Winston well understood the boy. Willie Lee was mentally handicapped but not a baby, and not deaf, either—as so many tended to treat him in his old age.

Corrine and her aunt Marilee continued to stand and watch as the men and boy and dog got into the Bronco that Papa Tate already had warming up. Doors slammed. The Bronco went backing out, and then Aunt Marilee hollered, “Watch out!”

Although Papa Tate no doubt could not hear her with the windows rolled up, he had already slammed on his brakes, avoiding hitting Mr. Everett’s Honda Accord backing out of his driveway so fast that the rear end bounced two feet when the tires hit the street. Then the Honda roared off ahead of the Bronco.

Aunt Marilee looked at Corrine, and Corrine looked back at her. With sighs, they went back in the warm house, turning out the porch light.

At the radio station, Everett had gotten into the sound studio and sat himself in the executive chair at the microphone. He cast a wave to Tate, who bid him good-morning.

Winston took note of the situation. There were two more rolling chairs, both smaller and against the wall. Winston had never sat in either. He was a big man, and required a big chair.

He turned and went to get a cup of coffee, then returned to stand in the studio doorway, sipping it. Everett studiously kept his gaze on some papers in front of him. Tate was leaning over and having a discussion with Jim Rainwater at the controls. Willie Lee had taken one of the chairs against the wall, as he usually did, with his dog’s chin on his still-untied shoe. He grinned with some excitement at Winston, who shot him a wink.

A check of the clock. Two minutes to on-air.

“Tate…could I speak to you and Everett a moment?”

Tate turned. Everett sat there, blinking behind his glasses.

Winston said sweetly, “Just a minute before airtime, Ev.” Tate turned his gaze to the other man, causing him to reluctantly get up and come out of the room.

“I just want to say thanks for the opportunity, Tate, and thanks for joinin’ us, Everett. I know we’re gonna have us a time.” As Winston spoke, he eased himself around the men and slipped through the studio door, and headed directly for the big armchair at the microphone. In one movement, he plopped down and put the headphone to his ear with one hand, reaching for the microphone with the other.

“You dang…” Everett was beside himself.

“Thirty seconds,” said Jim Rainwater.

Everett pulled one of the smaller chairs over and took hold of the microphone. Winston did not let go. The two glared at each other. Tate threw up his hands and walked out.

Jim Rainwater counted, “Five…four…three…two…you’re…on.” His finger pointed.

Winston jerked the microphone toward him. “Goooood mornin’, Valentinites! Rise and shine. GET UP, GET UP, YOU SLEE-PY-HEAD. GET UP AND GET YOUR BOD-Y FED!”

For the last part, Everett joined in, his face jutted so close to Winston that they about rubbed whiskers. The result was the call coming out sort of like an echo: “GET-et YOUR-or BOD-od-Y-ee FED-ed!”

“You’re listenin’ to the Wake Up call with Winston…”

“And Everett!”

“And Willie Lee and Munro!” Willie Lee had squeezed in between the two old men. Munro let out a bark.

“Wa-ake UP, ev-ery-bod-y!” said Willie Lee happily, followed by another bark from Munro and Jim Rainwater’s sound track of a trumpet playing reveille.

The audience share had increased tenfold over the past two days as word had spread about the reveille and the feud. People all over town tuned in just to hear the amazing Wake Up call from one—now four—of their own. Truckers picked up the radio out on the highway, and there were even a few listeners from as far away as Kansas and West Texas, people who experienced the early-morning show out of Valentine via skips in the signal.

Many listeners had their radio volumes turned up in order to join in with the reveille. The Dallas route bus driver, Cleon Salazar, was one of these. He sang out, helping to wake himself up and jarring a number of his dozing passengers.

Deputy Lyle Midgette, a perpetually cheerful soul, also joined in, repeating the words at the top of his voice as he drove home, windows wide and cold air snatching his breath.

Woody Beauchamp, an equally cheerful soul, reached over the pan of hot biscuits just in time to turn up the volume on the radio and holler out. His new friend, Andy Smith, jumped and almost fell back out the door, while upstairs in her bathroom, Fayrene Gardner stamped on the floor.

Rosalba Garcia stood ready with a pot lid and wooden spoon. At the yell from her radio, she went calling out and banging over the beds in her all-male household. At the discovery of the empty bed of her youngest, she was alarmed, until she looked under the bed and found that, after two mornings, he had anticipated her actions and gone to sleep underneath, with pillows and quilts as insulation. Not to be thwarted—this was the son born in America and she meant him to go to college—Rosalba dragged him out by his ankle.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, there were a number of listeners who deliberately tuned out, or at least down. These people wanted to hear the pertinent information of the weather and road conditions, school lunch menu and sales at the IGA, but they did not want to be jarred out of their skins, nor did they want anyone else in their household to be awakened.

Having gotten Aunt Marilee back to bed with both tiny tots, Corrine went all over the house, making certain every radio was turned off. Then she fell gratefully back into her own bed for another half hour’s sleep before getting up for school. One needed sleep when one lived in a nuthouse.

Across the street, Doris Northrupt sighed peacefully, giving thanks that her husband was gone, and that she could sleep to midmorning, when he would return. Retired life was good.

Julia Jenkins-Tinsley used the new iPod she had purchased the previous day; however, she couldn’t get it to work, so she had to jog listening to her own breathing in the cold morning air.

Inez Cooper turned her kitchen radio off in midreveille. “Idiots,” she said, as she counted her husband’s morning pills into the little medicine cup. She stuck in one of the quit-smoking herbal pills Belinda had given her. Norman would never notice an extra pill. She had gone all over his workshop and found two packages of hidden cigarettes, which she had torn up into the trash. Now, with firm determination, she set a small pamphlet about quitting smoking next to the coffeemaker.

Out at the edge of town, John Cole Berry was filling a travel mug of coffee and remembered just in time to punch the button that silenced the radio on the coffee machine. Standing there, sipping his coffee with both relief that Emma still slept and anxiousness about the busy day ahead, he felt a tightness come across his chest. He did not have time for Emma’s worries to transfer to him, he thought, taking up his jacket and slipping from the house. He was able to catch the reveille fifteen minutes later on his truck radio and have a good laugh.

Having slept a peaceful night in her own bedroom, Paris Miller was putting on her eye makeup while listening to her boom box set to low volume. She smiled at the Wake Up call. She loved sweet Willie Lee and Munro, and Mr. Winston, too, who had always been so kind to her. Sometimes she imagined her grandfather was like Mr. Winston; he could be, if only he would stop drinking. Turning off the radio, she tiptoed to the kitchen, carefully closing the door to her grandfather’s room as she passed. She prepared the coffeemaker, and set out an orange and a packaged sausage biscuit, all in readiness for her grandfather when he got up. If she could just love him enough, he would quit drinking.

Two miles away in her king-size bed with the leather head-board, Belinda slept soundly beneath fine Egyptian 1200-count cotton sheets and down comforter, head cradled on a soft pillow, with earplugs and a violet satin eye mask. A few feet away to the right, on the night table near her head, was a small decorative plaque, which she had purposely placed there the previous night. It read: Today I will be handling all of your problems. I do not need your help. —God.