Полная версия

Полная версияDiary in America, Series Two

The Utica railroad is the best in the United States. The general average of speed is from fourteen to sixteen miles an hour; but on the Utica they go much faster.3 A gentleman narrated to me a singular specimen of the ruling passion which he witnessed on an occasion when the rail-cars were thrown off the road, and nearly one hundred people killed, or injured in a greater or less degree.

On the side of the road lay a man with his leg so severely fractured, that the bone had been forced through the skin, and projected outside his trowsers. Over him hung his wife, with the utmost solicitude, the blood running down from a severe cut received on her head, and kneeling by his side was his sister, who was also much injured. The poor women were lamenting over him, and thinking nothing of their own hurts; and he, it appears, was also thinking nothing about his injury, but only lamenting the delay which would be occasioned by it.

“Oh! my dear, dear Isaac, what can be done with your leg?” exclaimed the wife in the deepest distress.

“What will become of my leg!” cried the man. “What’s to become of my business, I should like to know?”

“Oh! dear brother,” said the other female, “don’t think about your business now; think of getting cured.”

“Think of getting cured—I must think how the bills are to be met, and I not there to take them up. They will be presented as sure as I lie here.”

“Oh! never mind the bills, dear husband—think of your precious leg.”

“Not mind the bills! but I must mind the bills—my credit will be ruined.”

“Not when they know what has happened, brother. Oh! dear, dear—that leg, that leg.”

“D—n the leg; what’s to become of my business,” groaned the man, falling on his back from excess of pain.

Now this was a specimen of true commercial spirit. If this man had not been nailed to the desk, he might have been a hero.

I shall conclude this chapter with an extract from an American author, which will give some idea of the indifference as to loss of life in the United States.

“Every now and then is a tale of railroad disaster in some part of the country, at inclined planes, or intersecting points, or by running off the track, making splinters of the cars, and of men’s bones; and locomotives have been known to encounter, head to head, like two rams fighting. A little while previous to the writing of these lines, a locomotive and tender shot down the inclined plain at Philadelphia, like a falling star. A woman, with two legs broken by this accident, was put into an omnibus, to be carried to the hospital, but the driver, in his speculations, coolly replied to a man, who asked why he did not go on?—that he was waiting for a full load.”

Volume One—Chapter Three

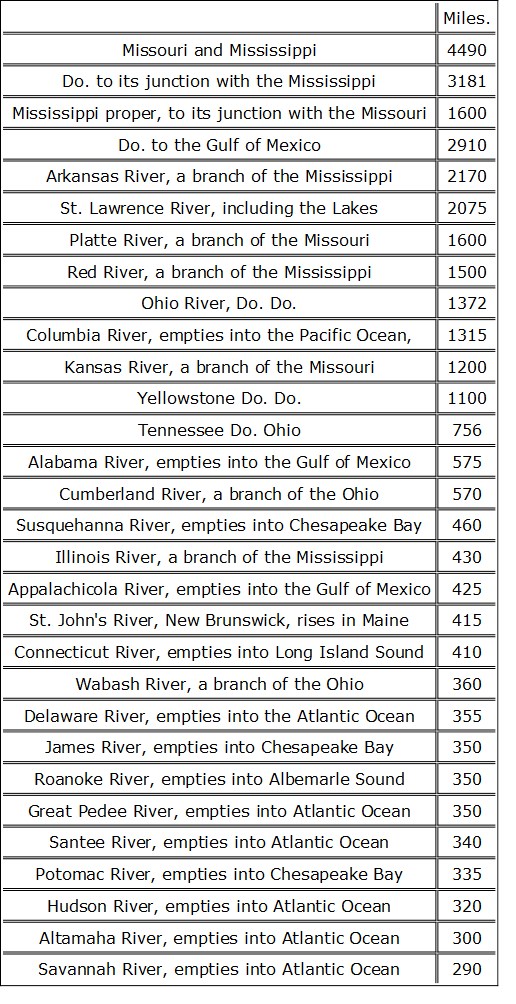

TravellingThe most general, the most rapid, the most agreeable, and, at the same time, the most dangerous, of American travelling is by steam boats. It will be as well to give the reader an idea of the extent of this navigation by putting before him the lengths of some of the principal rivers in the United States.

Voice from America.

Many of the largest of these rivers are at present running through deserts—others possess but a scanty population on their banks; but, as the west fills up, they will be teeming with life, and the harvest of industry will freight many more hundreds of vessels than those which at present disturb their waters.

The Americans have an idea that they are very far ahead of us in steam navigation, a great error which I could not persuade them of. In the first place, their machinery is not by any means equal to ours; in the next, they have no sea-going steam vessels, which after all is the great desideratum of steam navigation. Even in the number and tonnage of their mercantile steam vessels they are not equal to us, as I shall presently show, nor have they yet arrived to that security in steam navigation which we have.

The return of vessels belonging to the Mercantile Steam Marine of Great Britain, made by the Commissioners on the Report of steam-vessel accidents in 1839, is, number of vessels, 810; tonnage, 157,840; horse power, 63,250.

Mr Levi Woodbury’s Report to Congress in December, 1838, states the number of American steam vessels to be 800, and the tonnage to be 155,473; horse power, 57,019.

It is but fair to state, that the Americans have the credit of having sent the first steam vessel across the Atlantic. In 1819, a steam vessel, built at New York, crossed from Savannah to Liverpool in twenty-six days.

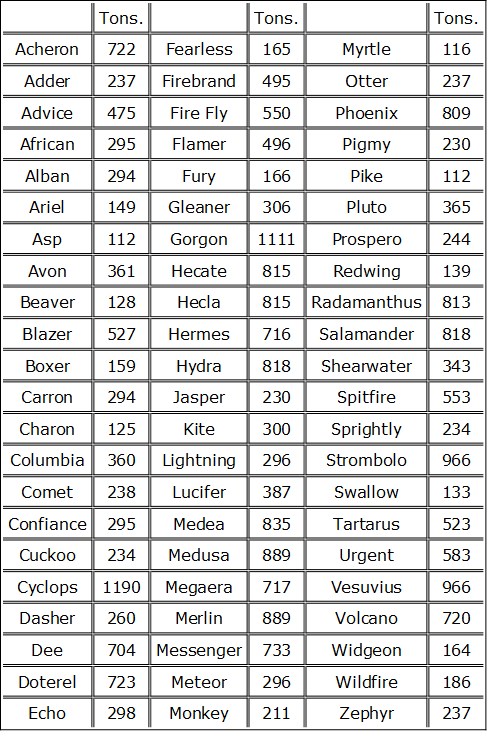

The number of sea-going steam vessels in England is two hundred and eighty-two, while in the United States they have not more than ten at the outside calculation. In the size of our vessels also we are far superior to them. I here insert a table, shewing the dimensions of our largest vessels, as given in the Report to the House of Commons, and another of the largest American vessels collected from the Report of Mr Levi Woodbury to Congress.

Table shewing some of the Dimensions of the Hull and Machinery of the five largest ships yet built or building.

(Table to be added in a later edition.)

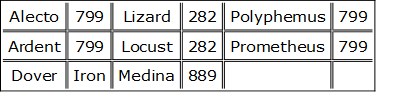

But the point on which we are so vastly superior to the Americans, is in our steam vessels of war. They have but one in the United States, named the Fulton the Second. The following is a list of those belonging to the Government of Great Britain, with their tonnage:—

Government Steam Vessels Building.

I trust that the above statement will satisfy the Americans that we are ahead of them in steam navigation. In consequence of their isolation, and having no means of comparison with other countries, the Americans see only their own progress, and seem to have forgotten that other nations advance as well as themselves. They appear to imagine that while they are going ahead all others are standing still: forgetting that England with her immense resources is much more likely to surpass them than to be left behind.

We must now examine the question of the proportionate security in steam boat travelling in the two countries. The following table, extracted from the Report of the Commissioners on Steam boat Accidents, will show the casualties which have occurred in this country in ten years.

Abstract of ninety-two Accidents. Table not included.

The principal portion of this loss of life has been occasioned by vessels having been built for sale, and not sea-worthy; an occurrence too common, I am afraid, in both countries.

The author of “A Voice from America” states the list of steamboat disasters, on the waters of the United States, for twelve months out of the years 1837-38, by bursting of boilers, burning, wrecks, etcetera, besides numerous others of less consequence, comprehends the total loss of eight vessels and one thousand and eighty lives.

So that we have in England, loss in ten years, 634; one year, 63.

In America, loss in one year, 1,080.

The report of Mr Woodbury to Congress is imperfect, which is not to be wondered at, as it is almost impossible to arrive at the truth; there is, however, much to be gleaned from it. He states that, since the employment of steam vessels in the United States, 1,300 have been built, and of them two hundred and sixty have been lost by accidents.

The greatest loss of life by collision and sinking, was in the Monmouth, (Indians transporting to the West), in 1837, by which three hundred lives were lost; Oronoka, by explosion, by which one hundred and thirty or more lives were lost and Moselle, at Cincinnati, by which from one hundred to one hundred and twenty lives were lost.

The greatest loss by shipwreck was in the case of the Home, on the coast of South Carolina, when one hundred lives were lost; the greatest by fire, the Ben Sherrod, in 1837, by which one hundred and thirty perished.

The three great casualties which occurred during my stay in America, were those of the Ben Sherrod, by fire; the Home, by wreck; and the Moselle, by explosion: and as I have authentic details of them, by Americans who were on board, or eye-witnesses, I shall lay them before my readers. The reader will observe that there is a great difference in the loss of life mentioned in Mr Woodbury’s report and in the statements of those who were present. I shall hereafter state why I consider the latter as the more correct.

Loss of the Ben Sherrod, by a Passenger“On Sunday morning, the 6th of May 1837, the steam-boat Ben Sherrod, under the command of Captain Castleman, was preparing to leave the levée at New Orleans. She was thronged with passengers. Many a beautiful and interesting woman that morning was busy in arranging the little things incident to travelling, and they all looked forward with high and certain hope to the end of their journey. Little innocent children played about in the cabin, and would run to the guards—the guards of an American steam-boat are an extension of the deck on each side, beyond the paddle boxes, which gives great width for stowage—now and then, to wonder, in infantine language, at the next boat, or the water, or something else that drew their attention. “Oh, look here, Henry—I don’t like that boat, Lexington.”—“I wish I was going by her,” said Henry, musingly. The men too were urgent in their arrangements of the trunks, and getting on board sundry articles which a ten days’ passage rendered necessary. In fine all seemed hope, and joy, and certainty.

“The cabin of the Ben Sherrod was on the upper deck, but narrow in proportion to her build, for she was what is technically called a Tennessee cotton boat. To those who have never seen a cotton boat loaded, it is a wondrous sight. The bales are piled up from the lower guards wherever there is a cranny until they reach above the second deck, room being merely left for passengers to walk outside the cabin. You have regular alleys left amid the cotton in order to pass about on the first deck. Such is a cotton boat carrying from 1,500 to 2,000 bales.

“The Ben’s finish and accommodation of the cabin was by no means such as would begin to compare with the regular passenger boats. It being late in the season, and but few large steamers being in port in consequence of the severity of the times, the Ben Sherrod got an undue number of passengers, otherwise she would have been avoided, for her accommodations were not enticing. She had a heavy freight on board, and several horses and carriages on the forecastle. The build of the Ben Sherrod was heavy, her timbers being of the largest size.

“The morning was clear and sultry—so much so, that umbrellas were necessary to ward off the sun. It was a curious sight to see the hundreds of citizens hurrying on board to leave letters, and to see them coming away. When a steam-boat is going off on the Southern and Western waters, the excitement is fully equal to that attendant upon the departure of a Liverpool packet. About ten o’clock AM the ill-fated steamer pushed off upon the turbid current of the Mississippi, as a swan upon the waters. In a few minutes she was under way, tossing high in air, bright and snowy clouds of steam at every half revolution of her engine. Talk not of your northern steam-boats! A Mississippi steamer of seven hundred tons burthen, with adequate machinery, is one of the sublimities of poetry. For thousands of miles that great body forces its way through a desolate country, against an almost restless current, and all the evidence you have of the immense power exerted, is brought home to your senses by the everlasting and majestic burst of exertion from her escapement pipe, and the ceaseless stroke of the paddle wheels. In the dead of night, when amid the swamps on either side, your noble vessel winds her upward way—when not a soul is seen on board but the officer on deck—when nought is heard but the clang of the fire-doors amid the hoarse coughing of the engine, imagination yields to the vastness of the ideas thus excited in your mind, and if you have a soul that makes you a man, you cannot help feeling strongly alive to the mightiness of art in contrast with the mightiness of nature. Such a scene, and hundreds such have I realised, with an intensity that cannot be described, always made me a better man than before. I never could tire of the steam-boat navigation of the Mississippi.

“On Tuesday evening, the 9th of May 1837, the steam-boat Prairie, on her way to St. Louis, bore hard upon the Sherrod. It was necessary for the latter to stop at Fort Adams, during which the Prairie passed her. Great vexation was manifested by some of the passengers, that the Prairie should get to Natchez first. This subject formed the theme of conversation for two or three hours, the captain assuring them that he would beat her any how. The Prairie is a very fast boat, and under equal chances could have beaten the Sherrod. So soon as the business was transacted at Fort Adams, for which she stopped, orders were given to the men to keep up their fires to the extent. It was now a little after 11 p.m. The captain retired to his berth, with his clothes on, and left the deck in charge of an officer. During the evening a barrel of whisky had been turned out, and permission given to the hands to do as they pleased. As may be supposed, they drew upon the barrel quite liberally. It is the custom on all boats to furnish the firemen with liquor, though a difference exists as to the mode. But it is due to the many worthy captains now on the Mississippi, to state that the practice of furnishing spirits is gradually dying away, and where they are given, it is only done in moderation.

“As the Sherrod passed on above Fort Adams towards the mouth of the Homochitta, the wood piled up in the front of the furnaces several times caught fire, and was once or twice imperfectly extinguished by the drunken hands. It must be understood by those of my readers who have never seen a western steamboat, that the boilers are entirely above the first deck, and that when the fires are well kept up for any length of time, the heat is almost insupportable. Were it not for the draft occasioned by the speed of the boat it would be very difficult to attend the fires. As the boat was booming along through the water close in-shore, for, in ascending the river, boats go as close as they can to avoid the current, a negro on the beach called out to the fireman that the wood was on fire. The reply was, “Go to h—l, and mind your own business,” from some half intoxicated hand. “Oh, massa,” answered the negro, “if you don’t take care, you will be in h—l before I will.” On, on, on went the boat at a tremendous rate, quivering and trembling in all her length at every revolution of the wheels. The steam was heated so fast, that it continued to escape through the safety valve, and by its sharp singing, told a tale that every prudent captain would have understood. As the vessel rounded the bar that makes off from the Homochitta, being compelled to stand out into the middle of the river in consequence, the fire was discovered. It was about one o’clock in the morning. A passenger had got up previously, and was standing on the boiler deck, when to his astonishment, the fire broke out from the pile of wood. A little presence of mind, and a set of men unintoxicated, could have saved the boat. The passenger seized a bucket, and was about to plunge it overboard for water, when he found it locked. An instant more, and the fire increased in volumes. The captain was now awaked. He saw that the fire had seized the deck. He ran aft, and announced the ill-tidings. No sooner were the words out of his mouth, than the shrieks of mothers, sisters, and babes, resounded through the hitherto silent cabin in the wildest confusion. Men were aroused from their dreaming cots to experience the hot air of the approaching fire. The pilot, being elevated on the hurricane deck, at the instant of perceiving the flames, put the head of the boat shoreward. She had scarcely got under good way in that direction, than the tiller ropes were burnt asunder. Two miles at least, from the land, the vessel took a sheer, and, borne upon by the current, made several revolutions, until she struck off across the river. A (sand) bar brought her up for the moment.

“The flames had now extended fore and aft. At the first alarm several deck passengers had got in the yawl that hung suspended by the davits. A cabin passenger, endowed with some degree of courage and presence of mind, expostulated with them, and did all he could to save the boats for the ladies. ’Twas useless. One got out his knife and cut away the forward tackle. The next instant and they were all, to the number of twenty or more, launched onto the angry waters. They were seen no more.

“The boat being lowered from the other end, filled and was useless. Now came the trying moment. Hundreds leaped from the burning wreck into the waters. Mothers were seen standing on the guards with hair dishevelled, praying for help. The dear little innocents clung to the side of their mothers and with their tiny hands beat away the burning flames. Sisters calling out to their brothers in unearthly voices—‘Save me, oh save me, brother!’—wives crying to their husbands to save their children, in total forgetfulness of themselves,—every second or two a desperate plunge of some poor victim falling on the appalled ear,—the dashing to and fro of the horses on the forecastle, groaning audibly from pain of the devouring element—the continued puffing of the engine, for it still continued to go, the screaming mother who had leaped overboard in the desperation of the moment with her only child,—the flames mounting to the sky with the rapidity of lightning,—shall I ever forget that scene—that hour of horror and alarm! Never, were I to live till the memory should forget all else that ever came to the senses. The short half hour that separated and plunged into eternity two human beings has been so burnt into the memory that even now I think of it more than half the day.

“I was swimming to the shore with all my might, endeavoured to sustain a mother and her child. She sank twice, and yet I bore her on. My strength failed me. The babe was nothing—a mere cork. ‘Go, go,’ said the brave mother, ‘save my child, save my—’ and she sank, to rise no more. Nerved by the resolution of that woman, I reached the shore in safety. The babe I saved. Ere I had reached the beach, the Sherrod had swung off the bar, and was floating down, the engine having ceased running. In every direction heads dotted the surface of the river. The burning wreck now wore a new, and still more awful appearance. Mothers were seen clinging, with the last hope to the blazing timbers, and dropping off one by one. The screams had ceased. A sullen silence rested over the devoted vessel. The flames became tired of their destructive work.

“While I sat dripping and overcome upon the beach, a steam boat, the Columbus, came in sight, and bore for the wreck. It seemed like one last ray of hope gleaming across the dead gloom of that night. Several wretches were saved. And still another, the Statesman, came in sight. More, more were saved.

“A moment to me had only elapsed, when high in the heavens the cinders flew, and the country was lighted all round. Still another boat came booming on. I was happy that more help had come. After an exchange of words with the Columbus, the captain continued on his way under full steam. Oh, how my heart sank within me! The waves created by his boat sent many a poor mortal to his long, long home. A being by the name of Dougherty was the captain of that merciless boat. Long may he be remembered!

“My hands were burnt, and now I began to experience severe pain. The scene before me—the loss of my two sisters and brother, whom I had missed in the confusion, all had steeled my heart. I could not weep—I could not sigh. The cries of the babe at my side were nothing to me.

“Again—another explosion! and the waters closed slowly and sullenly over the scene of disaster and death. Darkness resumed her sway, and the stillness was only interrupted by the distant efforts of the Columbus and Statesman in their laudable exertions to save human life.

“Captain Castleman lost, I believe, a father and child. Some argue, this is punishment enough. No, it is not. He had the lives of hundreds under his charge. He was careless of his trust; he was guilty of a crime that nothing will ever wipe out. The bodies of two hundred victims are crying out from the depth of the father of waters for vengeance. Neither society nor law will give it. His punishment is yet to come. May I never meet him!

“I could tell of scenes of horror that would rouse the indignation of a stoic; but I have done. As to myself, I could tell you much to excite your interest. It was more than three weeks after the occurrence before I ever shed a tear. All the fountains of sympathy had been dried up, and my heart was as stone. As I lay on my bed the twenty-fourth day after, tears, salt tears, came to my relief, and I felt the loss of my sisters and brother more deeply than ever. Peace be to their spirits! they found a watery grave.

“In the course of all human events, scenes of misery will occur. But where they rise from sheer carelessness, it requires more than christian fortitude to forgive the being who is in fault. I repeat, may I never meet Captain Castleman or Captain Dougherty!

“I shall follow this tale of woe by some strictures on the mode of building steam-boats in the west, and show that human life has been jeopardised by the demoniac spirit of speculation, cheating and roguery. The fate of the Ben Sherrod shall be my text.”

It will be seen from this narrative, that the loss of the vessel was occasioned by racing with another boat, a frequent practice on the Mississippi. That people should run such risk, will appear strange but if any of my readers had ever been on board of a steam vessel in a race, they would not be surprised; the excitement produced by it is the most powerful that can be conceived—I have myself experienced it, and can answer for the truth of it. At first, the feeling of danger predominates, and many of the passengers beg the captain to desist: but he cannot bear to be passed by, and left astern. As the race continues, so do they all warm up, until even those who, most aware of the danger, were at first most afraid, are to be seen standing over the very boilers, shouting, huzzaing, and stimulating the fireman to blow them up; the very danger gives an unwonted interest to the scene; and females, as well as men, would never be persuaded to cry out, “Hold, enough!”

Another proof of the disregard of human life is here given in the fact of one steam-boat passing by and rendering no assistance to the drowning wretches; nay, it was positively related to me by one who was in the water, that the blows of the paddles of this steam-boat sent down many who otherwise might have been saved.

When I was on the Lakes, the wood which was piled close to the fire-place caught fire. It was of no consequence, as it happened, for it being a well-regulated boat, the fire was soon extinguished; but I mention it to show the indifference of one of the men on board. About half an hour afterwards, one of his companions roused him from his berth, shaking him by the shoulder to wake him, saying, “Get up, the wood’s a-fire—quick.” “Well, I knew that ’fore I turn’d in,” replied the man, yawning.

The loss of the Home occasioned many of the first families in the states to go into deep mourning, for the major portion of the passengers were highly respectable. I was at New York when she started. I had had an hour’s conversation with Professor Nott and his amiable wife, and had made arrangements with them to meet them in South Carolina. We never met again, for they were in the list of those who perished.

Loss of the Home“The steam-packet Home, commanded by Capt. White, left New York, for Charleston, South Carolina, at four o’clock, p.m., on Saturday, the 7th Oct. 1837, having on board between eighty and ninety passengers, and forty-three of the boat’s crew, including officers, making in all about one hundred and thirty persons. The weather at this time was very pleasant, and all on board appeared to enjoy, in anticipation, a delightful and prosperous passage. On leaving the wharf, cheerfulness appeared to fill the hearts and enliven the countenances of this floating community. Already had conjectures been hazarded, as to the time of their arrival at the destined port, and high hopes were entertained of an expeditious and pleasant voyage. Before six o’clock,—a check to these delusive expectations was experienced, by the boat being run aground on the Romer Shoal, near Sandy Hook. It being ebb tide, it was found impossible to get off before the next flood; consequently, the fires were allowed to burn out, and the boat remained until the flood tide took her off, which was between ten and eleven o’clock at night, making the time of detention about four or five hours. As the weather was perfectly calm, it cannot, reasonably, be supposed that the boat could have received any material injury from this accident; for, during the time that it remained aground, it had no other motion than an occasional roll on the keel from side to side. The night continued pleasant. The next morning, (Sunday,) a moderate breeze prevailed from the north-east. The sails were spread before the wind, and the speed of the boat, already rapid, was much accelerated. All went on pleasantly till about noon, when the wind had increased, and the sea became rough. At sunset, the wind blew heavily, and continued to increase during the night; at daylight, on Monday, it had become a gale. During the night, much complaint was made that the water came into the berths, and before the usual time of rising, some of the passengers had abandoned them on that account.